The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids, and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

The Ligurian leafhopper, Eupteryx decemnotata (Rey), is a sap-feeding insect in the family Cicadellidae. Like many other cicadellids, the adult Ligurian leafhopper has a wedge-shaped head, bristle-like antennae, and two pairs of wings that are folded over body at rest (Figure 1). Originally native to the Mediterranean basin around the Ligurian Sea, including parts of Italy, France, and islands such as Capraia and Sardinia, the Ligurian leafhopper has generated scientific and regulatory interest by rapidly increasing its geographic range over the past three decades (Nickel and Holzinger 2006). This range expansion may have been facilitated by commercial transportation of host plants in the mint family (Lamiaceae).

Credit: Katja Schulz, Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, photograph licensed by Creative Commons

Distribution

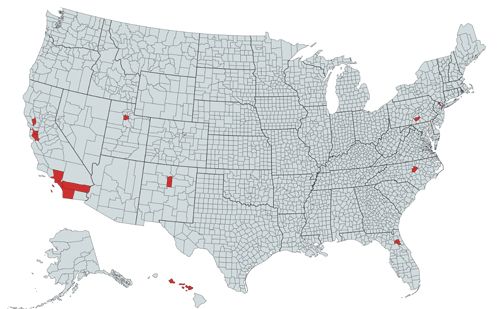

Prior to 1980, the Ligurian leafhopper was known only from the Mediterranean coasts of France and Italy but, starting in 1983, it began a northward spread into continental Europe via Switzerland and Austria, reaching Germany by 1989 (Nickel and Holzinger 2006). Adult or immature leafhoppers may have hitchhiked their way from country to country on imported catnip (Nepeta cataria (L.)) plants, which were becoming popular ornamental plants in the 1980s (Nickel and Holzinger 2006). Subsequently, the Ligurian leafhopper invaded the United Kingdom (Maczey and Wilson 2004), the United States (Rung et al. 2009), and Poland (Lubiarz and Musik 2015). Within the United States, the leafhopper has been reported from multiple individual sites in eight states, although collections made in Pennsylvania and Florida represent regulatory interceptions, and therefore may not imply the presence of an established population (Figure 2) (Halbert et al. 2009, Ciafré and Barringer 2017).

Credit: created by Alexander Tasi using mapchart.net, after descriptions in Rung et al. (2009), Ciafré and Barringer (2017), Kittleberger (2018), Dietrich and Perreira (2019), and BugGuide.net

Description and Life Cycle

Eggs

Adult females oviposit (lay eggs) within the leaf tissues of host plants (Mazzoni and Conti 2006). Leonard and Barber (1923) described eggs of a related species, the sage leafhopper (Eupteryx mellisae (Curtis)), as being 0.85 mm long and 0.17 mm wide, translucently white, and inserted within the petioles (leafstalks) of catnip leaves. If the eggs of the Ligurian leafhopper are of a similar size and coloration, regulators might easily overlook their presence while visually inspecting imported plants; however, Leonard and Barber (1923) noted that the oviposition punctures were marked by corresponding brown discolorations on the leaf surface, which may alert inspectors to the presence of eggs. In Italy, it is thought that most of the population overwinters as eggs. At 20°C, Ligurian leafhopper eggs hatch within 20 to 26 days after oviposition (Mazzoni and Conti 2006).

Nymphs

After the eggs hatch, the Ligurian leafhopper passes through five nymphal (immature) stages known as instars. At the end of each instar, the nymph molts (shedding its exoskeleton to increase in size). The 5th instar is the longest developmental stage and lasts approximately five days, after which the nymph molts into an adult. The entire nymphal period takes about 20 days (Mazzoni and Conti 2006). Nymphs are green, wingless, and covered in hair-like structures called setae (Figure 3). Like the adults, nymphs are capable of hopping.

Credit: Elena Regina, Flickr.com

Adults

The adults are less than 3 mm long, with a mottled, brown, yellow and white wing pattern (Halbert et al. 2009). Long hind legs allow the insects to jump rapidly when disturbed. Several rows of prominent spines on the hind legs are used to distribute water repellant secretions, known as bronchosomes, across exposed body parts (Burrows 2007). These secretions may protect the leafhoppers from becoming trapped by droplets of water, or their own sticky, sugar-rich waste (Rakitov and Gorb 2013).

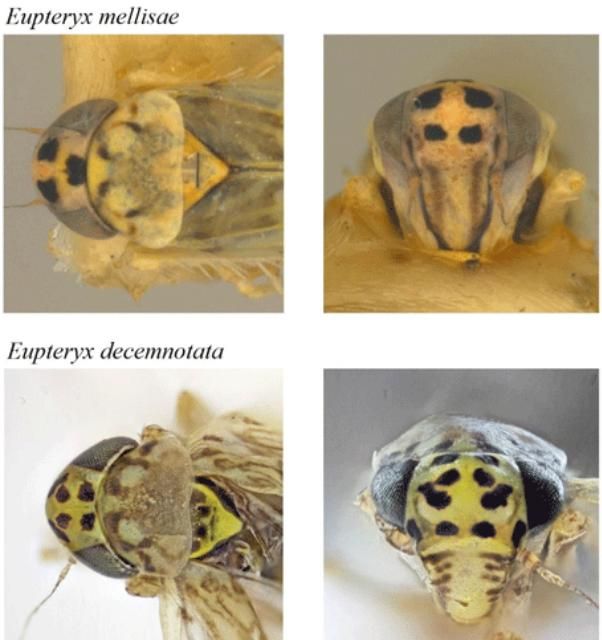

The Ligurian leafhopper can be distinguished from all other members of this genus by the presence of five pairs of black spots on the head, which are visible in anterior view (from the front of the body). One other member of this genus, the sage leafhopper, also occurs in the United States, and may be found on similar host plants (Halbert et al. 2009); however, the sage leafhopper has fewer than six black spots on the front of the head (Figure 4).

Members of the Typhlocybinae, the subfamily of leafhoppers to which the Ligurian leafhopper belongs, feed by piercing the leaves of their host plants with specialized, tube-like mouthparts (Stewart 1988). Multiple adults may be present on a single plant, which implies that some level of competition for feeding sites is tolerated among members of the same species. Eupteryx species, like many other small leafhoppers, have been found to produce species-specific courtship songs that are transmitted as vibrations through the leaves and stems of their hosts plants. Males and females of two British species (Eupteryx cyclops (Matsumara) and Eupteryx urticae (F.)) sing in alternating duos. The female generally remains stationary while the male approaches her (Stiling 1980).

Host Plants

The Ligurian leafhopper feeds on a wide variety of plants in the mint family (Nickel and Holzinger 2006). Many of these plants are widely planted for culinary and aesthetic purposes in farms and gardens. Within its native range, the leafhopper is reported to be common on both wild and cultivated herbs, and its feeding activity is associated with severe yellowing and branch drying of sage (Salvia officinalis) and rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) (Mazzoni 2005). Other host plants include lemon balm (Melissa officinalis), basil (Ocimum basilicum), marjoram (Origanum majorana), oregano (Origanum vulgare), and thyme (Thymus vulgaris). (Halbert et al. 2009). Like the Ligurian leafhopper, these host plants appear to have Mediterranean origins (Drew and Sytsma 2012).

Damage

In the United States over 150,000 acres of mint are grown each year, for both fresh market and essential oil production, and the market for herbal supplements is worth over 4 billion dollars (Craker et al. 2003). Feeding damage by leafhoppers in the genus Eupteryx is associated with lower essential oil content in Turkish oregano (Origanum onites) (Arslan et al. 2012), which suggests that overall mint essential oil yields might be impacted as well if the leafhopper reached damaging population levels in a field. The unsightly yellowing and stippling caused by Ligurian leafhopper feeding may also reduce the vigor and visual appeal of plants sold for human consumption or through the nursery trade. Damage to host plants reportedly increases with higher densities of feeding leafhoppers (Mazzoni and Conti 2006).

Members of the subfamily Typhlocybinae generally feed on the contents of mesophyll cells (non-vascular leaf tissue), and therefore may be less efficient at transmitting plant pathogens than hoppers feeding on xylem or phloem. At least one species in the subfamily is a known vector of phytopathogenic bacteria (Galetto et al. 2011). The Ligurian leafhopper specifically has not been shown to transmit any plant pathogens.

Management

Much of the published literature about Ligurian leafhopper management comes from Europe, rather than the United States, where it is still a relatively recent arrival. In Poland, herb producers reportedly vacuum plants and employ yellow sticky traps to reduce the abundance of Ligurian leafhopper during the growing season (Lubiarz and Musik 2015). Several applications of a neem seed derivative provided effective chemical control on rosemary grown under high tunnels in Switzerland (Crettenand and Mittaz 2001). Lastly, the eggs of Eupteryx sp. in Britain were parasitized by wasps resembling Anagrus atomus (L.) (Hymenoptera: Mymaridae) (Stewart 1988). These or similar wasps may be worth investigating as biological control agents if populations if Ligurian leafhopper achieve pest status in the United States.

Selected References

Arslan M, Uremis I, Demirel N. 2012. "Effects of sage leafhopper feeding damage on herbage colour, essential oil content and compositions of Turkish and Greek oregano." Experimental Agriculture 48: 428–437. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0014479712000075

Burrows M. 2007. "Kinematics of jumping in leafhopper insects (Hemiptera, Auchenorrhyncha, Cicadellidae)." Journal of Experimental Biology 210: 3579–3589. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.009092

Ciafré C, Barringer LE. 2017. "First record of the Ligurian leafhopper, Eupteryx decemnotata Rey (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) in Pennsylvania." Insecta Mundi 576: 1–2.

Craker L, Gardner Z, Etter SC. 2003. "Herbs in American fields: a horticultural perspective of herb and medicinal plant production in the United States, 1903 to 2003." Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 38: 977–983. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.38.5.977

Crettenand Y, Mittaz C. 2001. "Essais de lutte contre les cicadelles en culture de romarin sous abri." Revue Suisse de Viticulture, Arboriculture et Horticulture 33: 211–216.

Dietrich CH, Perreira WD. 2019. "Eight leafhoppers (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) newly recorded from Hawaii, including a new species." Annals of the Entomological Society of America 112: 281–287. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/saz004

Drew BT, Sytsma KJ. 2012. "Phylogenetics, biogeography, and staminal evolution in the tribe Mentheae (Lamiaceae)." American Journal of Botany 99: 933–953. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1100549

Galetto L, Marzachì C, Demichelis S, Bosco D. 2011. "Host plant determines the phytoplasma transmission competence of Empoasca decipiens (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae)." Journal of Economic Entomology 104: 360–366.

Halbert SE, Rung A, Ziesk DC, Gill RJ. 2009. A leafhopper pest of plants in the mint family, Eupteryx decemnotata Rey, Ligurian leafhopper, new to North America and intercepted in Florida on plants from California. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry Pest Alert, 1640. https://www.freshfromflorida.com/content/download/68538/1615137/Pest_Alert_-_Eupteryx_Decemnotata,_Ligurian_Leafhopper.pdf (30 Aug 2019).

Kittleberger K. 2018. Eupteryx decemnotata - Ligurian leafhopper. Hoppers of North Carolina. http://dpr.ncparks.gov/bugs/view_1.php?id=16538 (30 Aug 2019).

Leonard MD, Barber GW. 1923. T"he immature stages of the catnip leafhopper (Eupteryx melissae Curtis)." Journal of the New York Entomological Society 31: 181–184.

Lubiarz M, Musik K. 2015. "First record in Poland of the Ligurian leafhopper, Eupteryx decemnotata Rey 1891 (Cicadomorpha, Cicadellidae)–an important pest of herbs." Journal of Plant Protection Research 55: 324–326. https://doi.org/10.1515/jppr-2015-0030

Maczey N, Wilson MR. 2004. "Eupteryx decemnotata Rey (Hemiptera, Cicadellidae) new to Britain." British Journal of Entomology and Natural History 17: 111–114.

Mazzoni V. 2005. "Contribution to the knowledge of the Auchenorrhyncha (Hemiptera Fulgoromorpha and Cicadomorpha) of Tuscany (Italy)." Redia 88: 85–102.

Mazzoni V, Conti B. 2006. "Eupteryx decemnotata Rey (Hemiptera Cicadomorpha Typhlocybinae), important pest of Salvia officinalis (Lamiaceae)." Acta Horticulturae 723: 453–458. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2006.723.65

Nickel H, Holzinger WE. 2006. "Rapid range expansion of Ligurian leafhopper, Eupteryx decemnotata Rey, 1891 (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae), a potential pest of garden and greenhouse herbs, in Europe." Russian Entomological Journal 15: 57–63.

Rung A, Halbert SE, Ziesk DC, Gill RJ. 2009. "A leafhopper pest of plants in the mint family, Eupteryx decemnotata Rey (Hemiptera: Auchenorrhyncha: Cicadellidae), Ligurian leafhopper, new to North America." Insecta Mundi 88: 1–4.

Rakitov R, Gorb SN. 2013. "Brochosomal coats turn leafhopper (Insecta, Hemiptera, Cicadellidae) integument to superhydrophobic state." Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 280: 20122391. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.2391

Stewart AJ. 1988. "Patterns of host-plant utilization by leafhoppers in the genus Eupteryx (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) in Britain." Journal of Natural History 22: 357–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222938800770261

Stiling PD. 1980. Competition and coexistence among Eupteryx leafhoppers (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) occurring on stinging nettles (Urtica dioica). The Journal of Animal Ecology 49: 793-805. https://doi.org/10.2307/4227