The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

The taro planthopper, Tarophagus colocasiae (Matsumura), is a sap-feeding insect in the family Delphacidae. Like other delphacids, Tarophagus colocasiae has a characteristic movable spur extending from the tibia, or fourth leg segment. Adults can be either capable of flight or have incompletely developed wings, leading to two separate morphological forms (Figure 1). Originally native to Southeast Asia, Indonesia, and islands in the Pacific Ocean, Tarophagus colocasiae was first discovered in the continental United States at a garden center in Winter Haven, FL in 2015 (Halbert and Bartlett 2015). No other species from its genus is currently found in the continental United States.

Credit: Alexander Tasi, UF/IFAS

Synonomy

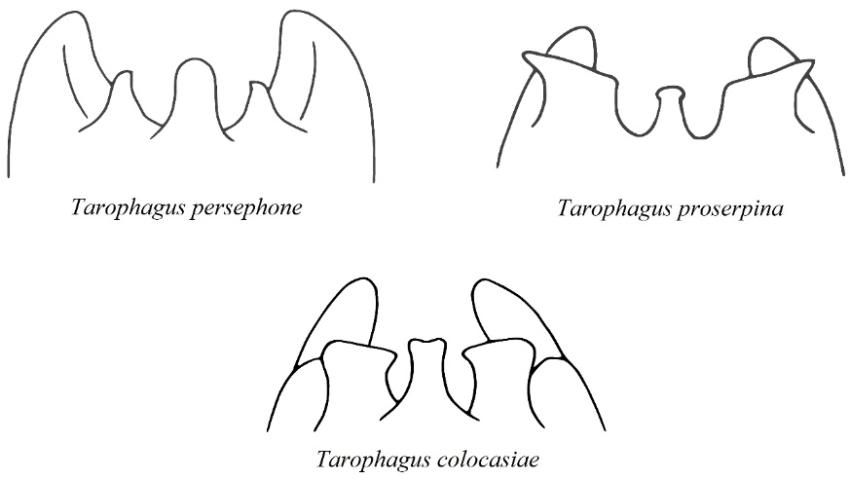

In 1989, the genus Tarophagus was revised based on morphological differences in the male genitalia and other distinguishing characters. Asche and Wilson (1989) split the species, Tarophagus proserpina, into three species: Tarophagus persephone (Kirkaldy), Tarophagus proserpina (Kirkaldy), and Tarophagus colocasiae (Matsumura). Because of this, some ambiguity exists as to what currently valid species is being described in older literature (articles from before 1989), within which Tarophagus colocasiae is identified as Tarophagus proserpina. However, each of the three newly delineated species have similar external appearances and host plants, and therefore likely have similar life histories (development and behavior).

Distribution

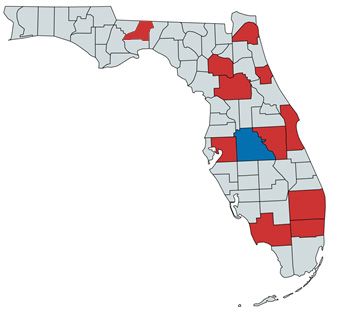

The current distribution of Tarophagus colocasiae includes much of mainland and maritime Southeast Asia, as well as islands throughout the Pacific. Specific collection records are present from, but not limited to, Thailand, Taiwan, Indonesia, Borneo, Papua New Guinea, Micronesia, Guam, and Hawaii (Bartlett 2018). In addition to the recent detection in Florida, the planthopper has also been reported from Cuba and Jamaica in the Caribbean (Bartlett 2018). The initial Florida collection was made in Polk County on taro (Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott) (Halbert and Bartlett 2015) (Figure 2). However, given that Polk County is landlocked and that the initial detection in Cuba was in December of 2014 (González Vázquez et al. 2016), slightly prior to the first discovery in Florida, it is possible that this planthopper entered the state somewhere else and spread from there to the center of the state.

Credit: Alexander Tasi using mapchart.net, based on communications with Susan Halbert, Florida Division of Plant Industry, and specimens vouchered in the Florida State Collection of Arthropods

Description and Life Cycle

Eggs

Adult females oviposit (lay eggs) within the petioles, or leaf stalks of host plants. Matsumoto and Nishida (1966) noted that oviposition sites of Tarophagus proserpina (likely Tarophagus colocasiae) on taro (Colocasia esculenta) could easily be recognized by the dark residue of sap that had oozed out from oviposition puncture wounds, and onto the petiole surface (Figure 3). These exudates also match descriptions from González Vázquez et al. (2016) of damage associated with Tarophagus colocasiae on taro plants in Cuba.

Credit: Alexander Tasi, UF/IFAS

The eggs themselves are ivory colored, slightly over a millimeter long, and are oriented roughly perpendicular to the petiole surface (Figure 4). Mean incubation time of the eggs under laboratory conditions was found to be around 14 days (Matsumoto and Nishida 1966).

Credit: Alexander Tasi, UF/IFAS

Nymphs

After the eggs hatch, Tarophagus colocasiae passes through five nymphal (juvenile) stages (called instars), before molting into an adult. The fifth instar takes around five days to develop, while each of the previous four instars takes around three days (Matsumoto and Nishida 1966). Nymphs start out paler than adults and darken as they mature (Bartlett 2018) (Figure 5). Like the adults, nymphs have characteristic tibial spurs and are capable of hopping. The juvenile planthoppers are gregarious and feed by inserting their piercing-sucking mouthparts into plant tissue and ingesting the sugar-rich phloem (one of two vascular fluids) that its host plant uses to transport energy. Heavy feeding can cause taro plants to severely yellow and wilt (Tasi pers. obs. 2020).

Credit: Alexander Tasi, UF/IFAS

Adults

The adults are small (between 2.5 and 4.1 mm or 0.1 and 0.16 in long), and mostly dark brown in color, with white markings on the thorax, just behind the head (Halbert and Bartlett 2015). Feeding, and consequent damage to the host plant, is much the same as it is for nymphs. Long hind legs provide adults with the ability to jump rapidly to escape predation. Adult males can be identified by ornamentation on the opening of their last abdominal segment, or pygofer, which is a distinctive feature for the genus, Tarophagus, and varies between each species (Bartlett 2018) (Figure 6). However, given the small size of the planthoppers, a powerful hand lens or microscope is required to distinguish between these slight differences in anatomy. Experts can also distinguish between the species by extracting and comparing differences in the morphology of the male genitalia (Asche and Wilson 1989). However, given that there is only one known species currently present in the continental United States, an aggregation of brown and white planthoppers on taro in Florida could be suspected with reasonable certainty to be Tarophagus colocasiae.

Credit: Adapted from Asche and Wilson (1989)

Hosts

Tarophagus colocasiae is a major pest of plants in the genus Colocasia (Halbert and Bartlett 2015). Colocasia esculenta, or taro, is grown for its edible, starchy tuber in many parts of the world. In the United States, plants from the family Araceae in the genera Colocasia, Alocasia, and Xanthosoma are commonly sold as landscape ornamentals, colloquially known as "elephant ears." Given that caged nymphs were also reported to survive for twenty-four hours on Caladium bicolor (Aiton) Vent., and Xanthosoma sp., among several other plant species, these plants may also be considered potential hosts in Florida (Duatin and de Pedro 1986).

Economic Importance

The economic impacts of Tarophagus colocasiae in Florida are currently unknown. Impacts would largely result from cosmetic damage, loss of nursery plants due to the unsightly and injurious results of feeding and oviposition, or regulatory quarantines imposed to prevent the spread of this insect. Wirth et al. (2004) estimated that annual Florida nursery sales of Colocasia esculenta were worth $868,000, accounting for .05% of total industry sales. While not commonly grown commercially for food in the continental United States, taro is a valued food plant in Hawaii, where it contributed $2.32 million to the economy in 2005 (Cozad et al. 2018). If Tarophagus colocasiae does infest and damage caladiums, it could be quite problematic for Florida nursery owners, who grow more than 95% of the caladium tubers used in the United States, Canada, Europe, and Asia (Deng 2012). Tarophagus planthoppers have also been implicated in the spread of Colocasia bobone disease virus, although that disease has only been reported at present from the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea (Yusop et al. 2019). Visible bobone disease symptoms on taro include stunting, thickened leaves, irregularly shaped galls on petioles, and necrosis, although infected plants generally recover (Revill et al. 2015).

Management

For delphacid planthoppers generally, invertebrate predators are the most important natural enemies: with wolf spiders (Lycosidae) attacking adults and nymphs, and mirid bugs (Miridae) feeding on eggs embedded within plant tissues (Denno and Peterson 2000). The predatory mirid bug, Cytorhinus fulvus Knight, has been used for biological control of Tarophagus species with variable success (Asche and Wilson 1989, Halbert and Bartlett 2015). Parasitoid wasps also attack delphacid eggs and nymphs but are generally considered less effective at controlling populations than predators (Denno and Peterson 2000). Successful management of the planthopper in a nursery setting would rely on integrated use of both insecticide applications and the considered maintenance of natural enemy populations. Some wolf spider species are commercially available as an augmentative biological control option.

Interestingly, Tarophagus colocasiae itself has been proposed as a biological control agent for ornamental Colocasia esculenta, which can be an invasive aquatic weed in the United States (Cozad et al. 2018) (Figure 7). While no formal biocontrol program of this plant is ongoing in the United States, the natural spread of Tarophagus colocasiae across Florida may have a deleterious effect on established invasive taro populations.

Credit: Alexander Tasi, UF/IFAS

Selected References

Asche M., and Wilson M. R. 1989. "The three taro planthoppers: species recognition in Tarophagus (Hemiptera: Delphacidae)." Bulletin of Entomological Research 79: 285–298. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007485300018277

Bartlett C. R. 2018. Genus Tarophagus Zimmerman 1948. Planthoppers of North America. https://sites.udel.edu/planthoppers/north-america/north-american-delphacidae/genus-tarophagus-zimmerman-1948/# (27 Sept. 2019).

Cozad, L. A, Harms, N., Russell, A. D, De Souza, M., and Diaz, R. 2018. "Is wild taro a suitable target for classical biological control in the United States?" Journal of Aquatic Plant Management 56: 1–12.

Deng, Z. 2012. "Fancy-leaved caladium varieties recently introduced by the UF/IFAS caladium breeding program." Proceedings of the Florida State Horticultural Society 125: 307–311.

Denno, R. F., and Peterson, M. A. 2000. "Caught between the devil and the deep blue sea, mobile planthoppers elude natural enemies and deteriorating host plants." American Entomologist 46: 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1093/ae/46.2.95

Duatin, C. J. Y, and De Pedro, L. B. 1986. "Biology and host range of the taro planthopper, Tarophagus proserpina Kirk." Annals of Tropical Research 8: 72–80.

Halbert, S. E., and Bartlett, C. R. 2015. "The taro planthopper, Tarophagus colocasiae (Matsumura), a new delphacid planthopper in Florida." Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry Pest Alert, 2040. https://www.fdacs.gov/ezs3download/download/61789/1413015/Media/Files/Plant-Industry-Files/Pest-Alerts/PEST%20ALERT%20Tarophagus%20colocasiae%20%28Matsumura%29.pdf (29 Sept. 2019).

González Vázquez, R. E., Castellón Valdés, M. D. C, and Grillo Ravelo, H. 2016. "Alcance de las lesiones causadas por Tarophagus colocasiae Matzumura (Auchenorhyncha: Delphacidae) en plantaciones de Colocasia esculenta Schott en Cuba." Revista de Protección Vegetal 31: 94–98.

Matsumoto, B. M., and Nishida, T. 1966. "Predator-prey investigations on the taro leafhopper and its egg predator." Hawaii Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Hawaii. Technical Bulletin 64.

Revill, P. A., Jackson, G. V. H, Hafnerc, G. J., Yang, I., Maino, M. K., Dowling, M. L., Devitt, L. C., Dal, J. L., and Harding, R. M. 2005. "Incidence and distribution of viruses of taro (Colocasia esculenta) in Pacific Island countries." Australasian Plant Pathology 34: 327–331.

Wirth, F. F., Davis K. J., amd Wilson S. B. 2004. "Florida nursery sales and economic impacts of 14 potentially invasive landscape plant species." Journal of Environmental Horticulture 22: 12–16.

Yusop, M. S. M., Saad, M. F. M., Talip, N., Baharum, S. N., and Bunawan, H. 2019. "A Review on Viruses Infecting Taro (Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott)." Pathogens 8: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens8020056