Introduction

The American grasshopper, Schistocerca americana (Drury), occasionally causes serious damage to crops and ornamental plants, and their great abundance can be a nuisance. Fields can be invaded daily by the adult grasshoppers, which often roost at night in nearby trees and shrubs (Kuitert and Connin 1952). The short-winged nymphs are less mobile, of course, and normally reside within sunny fields, as the grasshoppers avoid shade. Their eggs are deposited in the soil.

Credit: Tom Friedel

Distribution

In North America, the American grasshopper is found east of the Great Plains (Capinera et al. 2004), throughout the Southeast and north to near Iowa and Pennsylvania. It is common throughout Florida and is also found in Mexico and the Bahamas.

Description

Adults

The overall color gradually changes from a pinkish-brown or reddish-brown to more of a yellowish-brown hue as the grasshopper reaches sexual maturity. The adults bear fully developed wings with large dark brown spots on a lighter background. Adults are distinctly different in appearance from the immature stages (nymphs). The length of the male is 39 to 45 mm (1 ½ to 1 ¾ in), whereas the female is 42 to 55 mm (1 2/3 to 2 1/8 in) long.

Credit: John Capinera, UF/IFAS

Eggs

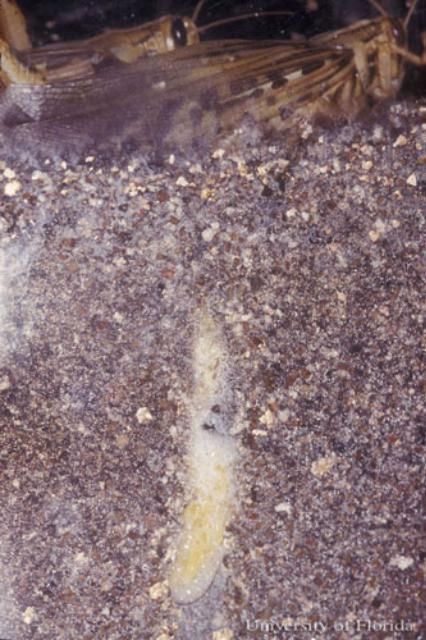

The female American grasshopper deposits her eggs in the soil about 2 to 3 cm (3/4 to 1 1/8 in) below the surface by pushing her ovipositor down into the substrate. The grasshoppers prefer areas with some ground cover to deposit their egg clusters, but not dense sod (Griffiths and Thompson 1952). The egg cluster generally consists of 60 to 80 eggs that are secured together by a frothy substance that the female secretes. Females may lay up to three egg pods. The eggs are 7 to 8 mm (1/4 to 1/3 in) in length and are light yellow-orange in color (Kuitert and Connin 1952).

Credit: John Capinera, UF/IFAS

Nymphs

The nymphs hatch three to four weeks after the eggs are deposited and must work their way to the surface. The nymphs go through five or six instars before reaching adulthood. Initially the nymphs remain aggregated in small groups, moving from plant to plant and feeding gregariously. As they grow older, they become less aggregated.

Credit: John Capinera, UF/IFAS

Six instars are normal, but if grasshopper densities are low only five instars will be completed. If there is a high density of nymphs, the latter instars will be more yellow, orange and black; at low densities, nymphs may be mostly green.

Credit: John Capinera, UF/IFAS

The developmental stage of the wings from no evidence of a wing, to small wing pads, to more developed wing pads, and finally fully formed wings is the easiest identifier for determining the instars (Capinera 1993a; Kuitert and Connin 1952).

The first instars are pale green with a black mid-dorsal stripe running the length of the body. The first instar is 6 to 9 mm (1/4 to 1/3 in) in length and has 13 antennal segments. Wing pads appear in the second instar as well as the addition of four more antennal segments; the second instar is usually 12 to 16 mm (1/2 to 2/3 in) long.

Credit: John Capinera, UF/IFAS

Credit: John Capinera, UF/IFAS

The third instars are 16 to 20 mm (2/3 to ¾ in) long and have 21 to 22 antennal segments. The wing pads are becoming evident now. They are found on the segments immediately behind the pronotum and are rounded-triangular lobes pointing downward.

Credit: John Capinera, UF/IFAS

In the fourth instar, which is 20 to 26 mm (3/4 to 1 in) long, rudimentary wing venation becomes present in the wing pads and the antennae have 22 to 24 segments. In this image, the wing pads (on the two segments behind the pronotum) are acquiring some black coloration, but this coloration is not always evident.

Credit: John Capinera, UF/IFAS

In the fifth instar the orientation of the wing pads undergoes "reversal" or "inversion," wherein the orientation changes from ventral to upward and obliquely posterior. This means that the wings are oriented upward but point horizontally and toward the abdomen instead of vertically, toward the ground. At this stage for the first time a structure that might be described as a small "wing" is evident. The fifth instar has a length of 27 to 35 mm (1 1/16 to 1 1/3 in) and 24 to 25 antennal segments.

Credit: John Capinera, UF/IFAS

The sixth instar is 32 to 45 mm (1 ¼ to 1 ¾ in) in length and has 25 to 26 antennal segments. The wings are larger now and extend back to cover several abdominal segments.

Credit: John Capinera, UF/IFAS

Life Cycle

The American grasshopper has two generations per year. It overwinters in the adult stage, unlike most grasshoppers, which pass the winter in the egg stage. Thus, American grasshoppers are present throughout the year in Florida. The principal hatching periods are from February to May, and again from August to September, but the generations may overlap (Griffiths and Thompson 1952).

Damage

The American grasshopper can cause injury to citrus, corn, cotton, oats, peanuts, rye, sugarcane, tobacco, and vegetables (Kuitert and Connin 1953). This species receives attention in Florida due to its defoliation of young citrus trees. The plants are damaged by the grasshopper gnawing on the leaves, and young vegetable plants can be eaten to the ground. Most of the feeding damage is caused by the third, fourth, and fifth instars. Those three stages have a much larger appetite than the adults. Aside from commercial crops, the American grasshopper also shows a preference for several species of grasses: bahiagrass, bermudagrass, crabgrass, nutgrass, and woodsgrass (Capinera 1993b). It also feeds on dogwood, hickory, palm trees, and probably others.

Credit: John Capinera, UF/IFAS

Credit: John Capinera, UF/IFAS

Credit: John Capinera, UF/IFAS

Significant damage to plants occurs when these insects become very abundant. Abundance commonly follows an increase in favored foods, typically weedy grasses (Capinera et al. 2001). This can result from weather that favors grasses such as mild winters, increased rainfall, suppression of grazing by livestock, or soil tillage. For example, if fields are not tilled after crop harvest or grasses are allowed to grow luxuriously in young pine plantations, weedy plant populations can develop that favor grasshopper survival and abundance. In contrast, short or sparse vegetation allows predators to detect and feed on grasshoppers, a favorite food of bird life.

Credit: John Capinera, UF/IFAS

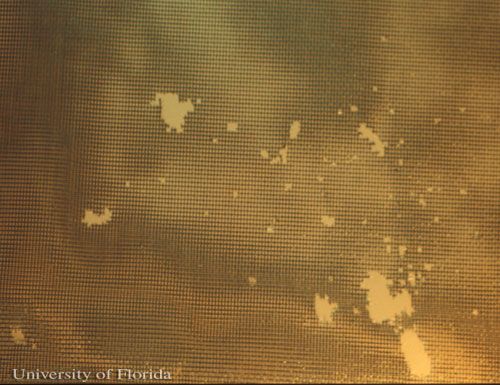

Grasshoppers maintain optimal temperature by climbing up and down vegetation, and by moving to more exposed (sunny) or less exposed (shady) locations. When they are abundant, they may climb up screen enclosures around pools, and up the sides of houses. Here they nibble their surroundings, and because their mouthparts (mandibles) are sharp, they can make holes in the fiberglass screening used as window and pool screens. This can be quite expensive to replace. The greatest level of damage is caused by last instar nymphs and young adults. This corresponds to the overall greater level of activity of these stages.

Credit: John Capinera, UF/IFAS

Management

Sampling

Grasshopper densities may be estimated using two methods. The first is to select a plot and determine area. The area can then be walked and the number of grasshoppers that leap or fly can be counted. This provides an estimate of number per unit of area, and when the numbers of late instar nymphs or adults exceed about 15 per square yard, there is potential for damage. The second method is to sweep the plot area with a sweep net to determine the average number of grasshoppers per sweep. The latter technique is a relative assessment that is only useful for distinguishing "high" from "low" density areas.

Biological Control

The only biological controls known for the American grasshopper affect the population on a small scale. The larvae of flies (Diptera: Sarcophagidae and Tachnidae) have been found to parasitize grasshoppers. Blister beetle (Coleoptera: Meloidae) and bee fly (Diptera: Bombyliidae) larvae, which live in the soil, will consume grasshopper eggs (Kuitert and Connin 1952).

Grasshoppers also fall prey to a number of birds. Cattle egrets consume large numbers and to a lesser extent so do robins, mockingbirds, and crows. Cattle egrets commonly are seen in association with cattle and horses and are quick to feed on grasshoppers disturbed by the feeding of these large animals.

One natural enemy that can be quite effective locally is the fungus Entomophaga grylli. Entomophaga grylli invokes a general condition called "summit disease". The name is derived from the fact that infected individuals climb to an elevated location (summit) where they die. This elevated location helps the pathogen to disperse, as spores eventually need to come into contact with the hoppers in order for the fungus to survive. Entomophaga grylli is not evident because the spores develop inside the body of the grasshopper. However, the dead grasshopper eventually disintegrates, allowing the fungal spores to be dispersed. The principal evidence of infection of Entomophaga grylli is the peculiar behavior of the dying and dead grasshoppers: they grasp vegetation tightly with their legs, even when dead, and die in an elevated location, with the head pointing upward.

Credit: John Capinera, UF/IFAS

Credit: John Capinera, UF/IFAS

The fungi Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium flavoviride have been tested for biological control but are not generally available. Nosema locustae is another pathogen, and it is one that is commercially available, but there are no data supporting its use for American grasshopper or any other grasshopper found in Florida, and its use is not recommended.

Cultural Control

Weeds are a major problem, encouraging high populations of grasshoppers. Mowing, disking, and plowing are good ways to reduce the abundance of weeds and in some cases to destroy grasshopper eggs and small nymphs (Kuitert and Connin 1953). In citrus groves, clean cultivation acts as a deterrent to oviposition and reduces the number of newly hatched nymphs. The time of cultivation is very important. If cultivation is too late, the grasshoppers may actually be driven to the crops for a source of food. In Florida, young pine plantations in which weed control is not practiced have yielded high levels of grasshoppers. These grasshoppers have been known to affect crop plants that are near the boundaries of the pine plantations. A continuous weed suppression program, resulting from tillage, application of herbicides, or mowing, can help avoid this problem.

Chemical Control

It is best to apply insecticide before the grasshoppers are adults as it is easier to kill the nymphs. For specific insecticide recommendations, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office: https://sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu/find-your-local-office/.

Selected References

Capinera JL. 1993a. "Differentiation of nymphal instars in Schistocerca americana (Orthoptera: Acrididae)." Florida Entomologist 76:176–79.

Capinera JL. 1993b. "Host-plant selection by Schistocerca americana (Orthoptera: Acrididae)." Environmental Entomology 22: 127–133.

Capinera JL, Scherer CW, Squitier JM. 2001. Grasshoppers of Florida. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

Capinera JL, Scott RD, Walker TJ. 2004. Grasshoppers, Katydids, and Crickets of the United States. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Dakin ME, Hays KL. 1970. A synopsis of Orthoptera (Sensu Lato) of Alabama. Auburn University Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 404.

Griffiths JT, Thompson WL. 1952. Grasshoppers in citrus groves. University of Florida Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 496: 1–26.

Kuitert LC, Connin RV. 1952. "Biology of the American grasshopper in the southeastern United States." Florida Entomologist 35: 22–33.

Kuitert LC, Connin RV. 1953. Grasshoppers and their control. University of Florida Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 516.

Thomas MC. 1991. "The American grasshopper, Schistocerca americana (Drury) (Orthoptera: Acrididae)." FDACS—Division of Plant Industry Entomology Circular 342.