Introduction

The hibiscus bud weevil (Anthonomus testaceosquamosus Linell, Coleoptera: Curculionidae) is a key insect pest of China rose hibiscus (Hibiscus rosa-sinensis L., Malvales: Malvaceae). This weevil originates from northeastern Mexico and southern Texas and was first found in Florida (in Miami-Dade County) in May 2017 (Skelley and Osborne 2018). It has since created severe hibiscus production and retail distribution challenges. According to ornamental nursery growers, increased weevil population densities in Homestead nurseries in 2019 and 2020 negatively impacted the hibiscus industry in south Florida during the spring shipping period, resulting in large economic losses. Florida leads hibiscus production nationally, and the majority of nursery production occurs in south Florida. Approximately 20%–25% of plants sold from Miami-Dade County are hibiscus, where the market value of ornamental plants was $945,688 (farmgate price) in 2022 (United States Department of Agriculture 2022). To stop the spread and economic impact of the hibiscus bud weevil, the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry (FDACS-DPI) regulates this pest. Since the hibiscus bud weevil is a regulated pest, any nursery found with this weevil must sign and follow a compliance agreement with FDACS-DPI to reduce the chance of spreading the weevil. The purpose of this article is to provide nursery owners, homeowners, and other interested people with information for managing this serious pest.

Identification

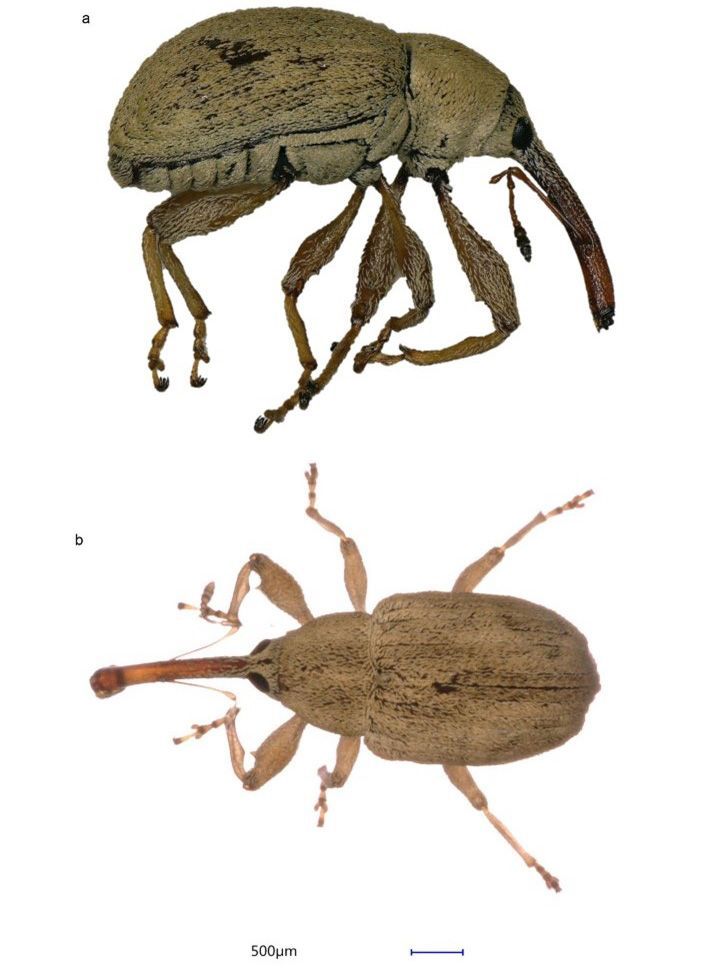

The hibiscus bud weevil is a beetle (Order Coleoptera) in the weevil family Curculionidae. It belongs to the Anthonomus squamosus species-group of the Anthonomini tribe. This species-group is characterized by weevils predominantly covered with scales and includes several native and exotic weevil species (Clark et al. 2019) (Figure 1). The adult body length is 2.5 mm–2.7 mm (~3/32 in) and the snout or beak is approximately 1 mm (1/32 in) long.

Credit: Daniel Carrillo, UF/IFAS TREC

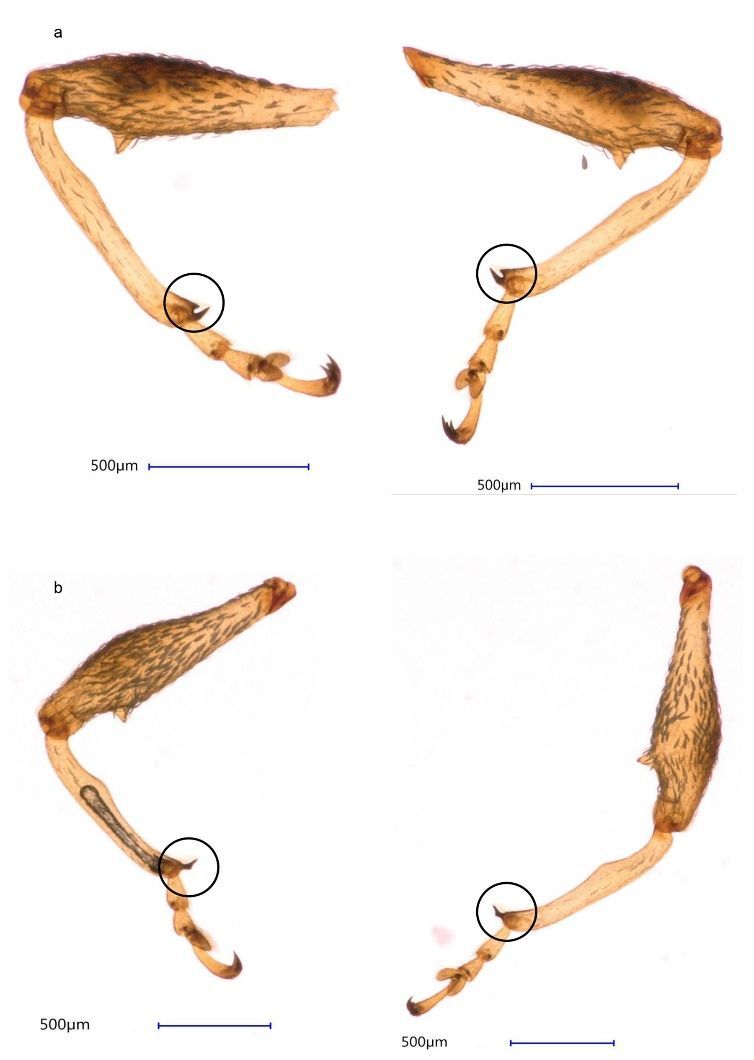

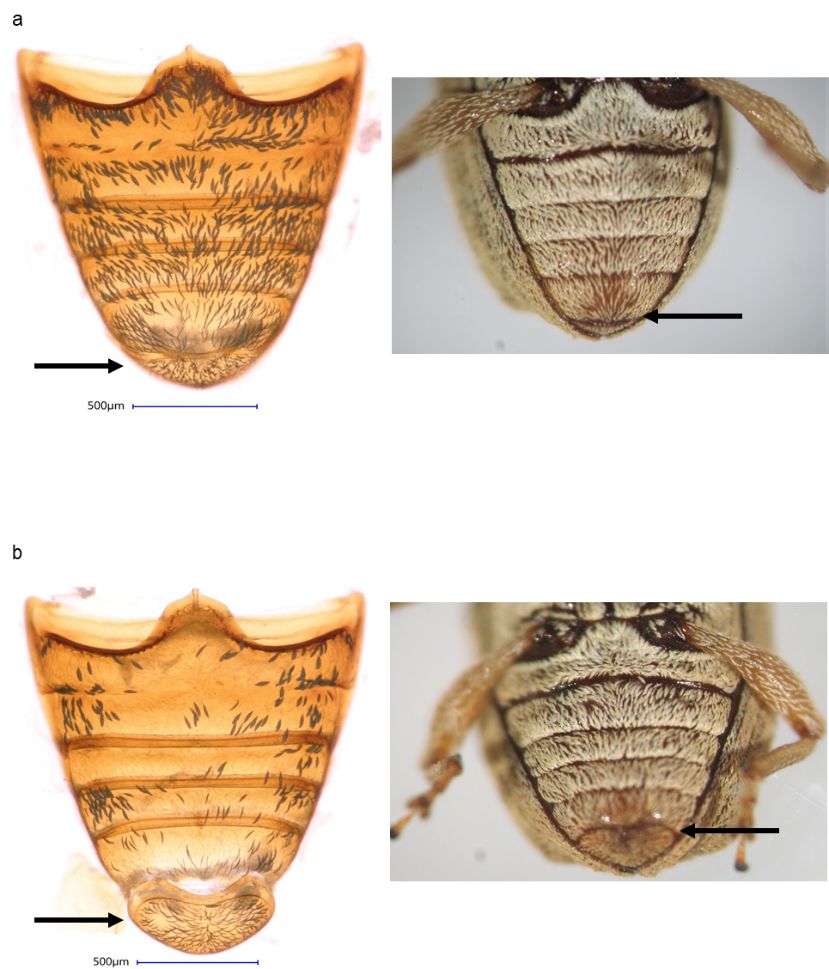

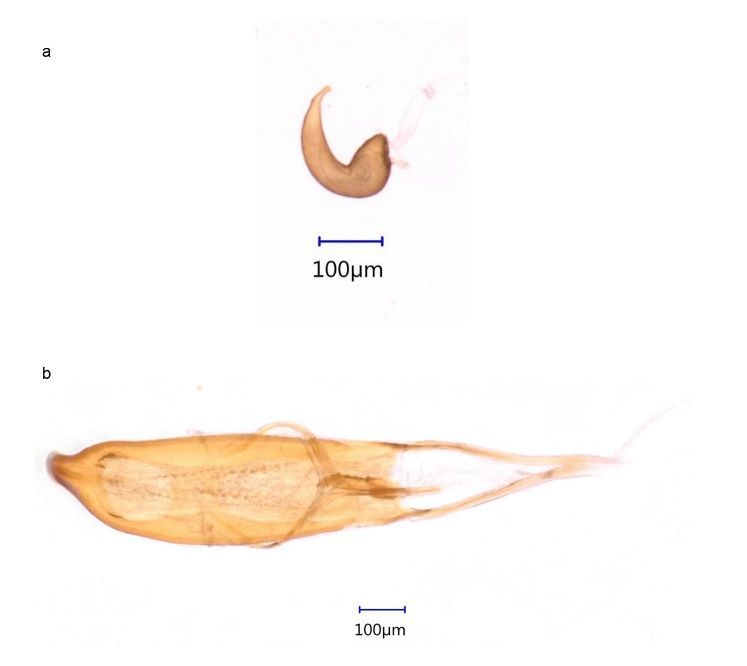

Females can be distinguished from males using two characters, one in the protibia (the fourth segment of the first pair of legs) and one in the abdomen. In the protibia, females have an apical uncus and subapical, inner-marginal prominence (mucron) (a spur-like structure on the inner side of the tibia) (Figure 2a), which is absent in males (Figure 2b). Additionally, the posterior part of the fifth ventrite (the margin of the fifth abdominal segment) in females is straight (Figure 3a, right) and in males is curved (Figure 3b, right). Moreover, females (Figure 3a, left) have a small pygidium (the last abdominal segment, exposed when the elytra are at rest) in comparison to males (Figure 3b, left). The validity of these characters was confirmed by dissecting weevil genitalia (Figure 4).

Credit: Daniel Carrillo, UF/IFAS TREC

Credit: Daniel Carrillo, UF/IFAS TREC

Credit: Daniel Carrillo, UF/IFAS TREC

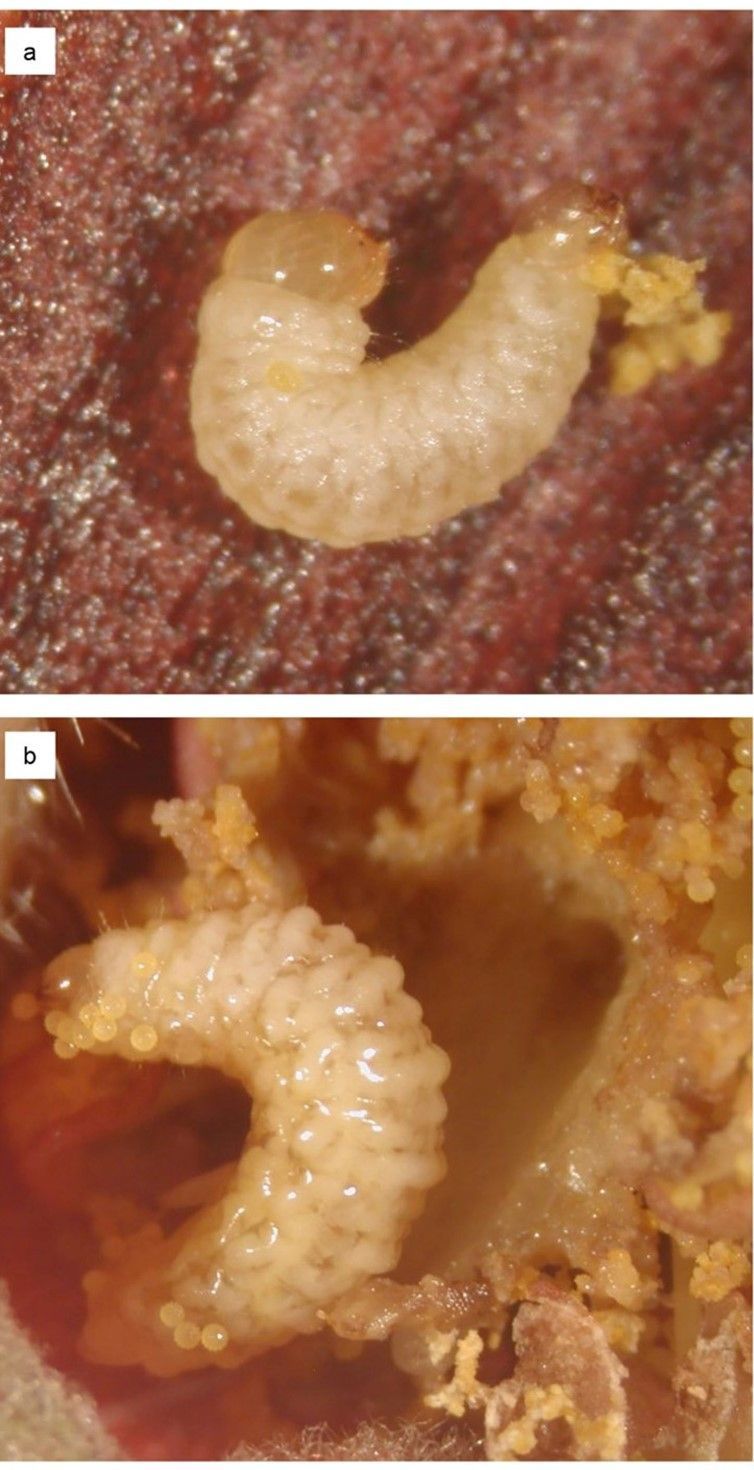

Eggs (Figure 5), which are deposited inside a hibiscus flower bud, are white when newly deposited and turn yellow as they mature. The larvae of the hibiscus bud weevil are transparent to yellow, have a well-developed head capsule, and lack thoracic legs (Figure 6). The size of an individual larva is somewhat limited by the size of the flower bud it occupies. In general, larger flower buds harbor larger larvae.

Credit: Juleysy Rodriguez and Yisell Velazquez-Hernandez, UF/IFAS TREC

Credit: Juleysy Rodriguez and Yisell Velazquez-Hernandez, UF/IFAS TREC

In Florida, another species from the Anthonomus squamosus species-group, Anthonomus rubricosus Boheman, has been reported infesting cotton and hibiscus plants (Clark et al. 2019; Loiácono et al. 2003). However, there are no reports showing its establishment in Florida. This weevil is similar in size to the hibiscus bud weevil but is brown. The Anthonomus genus includes several pest species of great agricultural importance, such as the cotton boll weevil, Anthonomus grandis Boheman. The most economically important Anthonomus pests reported in Florida are the pepper weevil, Anthonomus eugenii Cano, and the acerola weevil, Anthonomus macromalus Gyllenhal. The pepper weevil attacks plants of the family Solanaceae, particularly peppers (Capsicum spp.) (Capinera 2002), while the acerola weevil attacks Barbados cherry (Malpighia glabra, Family: Malpighiaceae) (Hunsberger and Pena 1998).

Host Range and Damage

Weevils belonging to the Anthonomus squamosus species-group are associated with plant species in the families, Asteraceae or Malvaceae. The hibiscus bud weevil, Anthonomus testaceosquamosus, has been associated with 15 plant species, all from the family Malvaceae (Table 1).

Table 1. Plant species on which the hibiscus bud weevil Anthonomus testaceosquamosus Linell has been found (Clark et al. 2019).

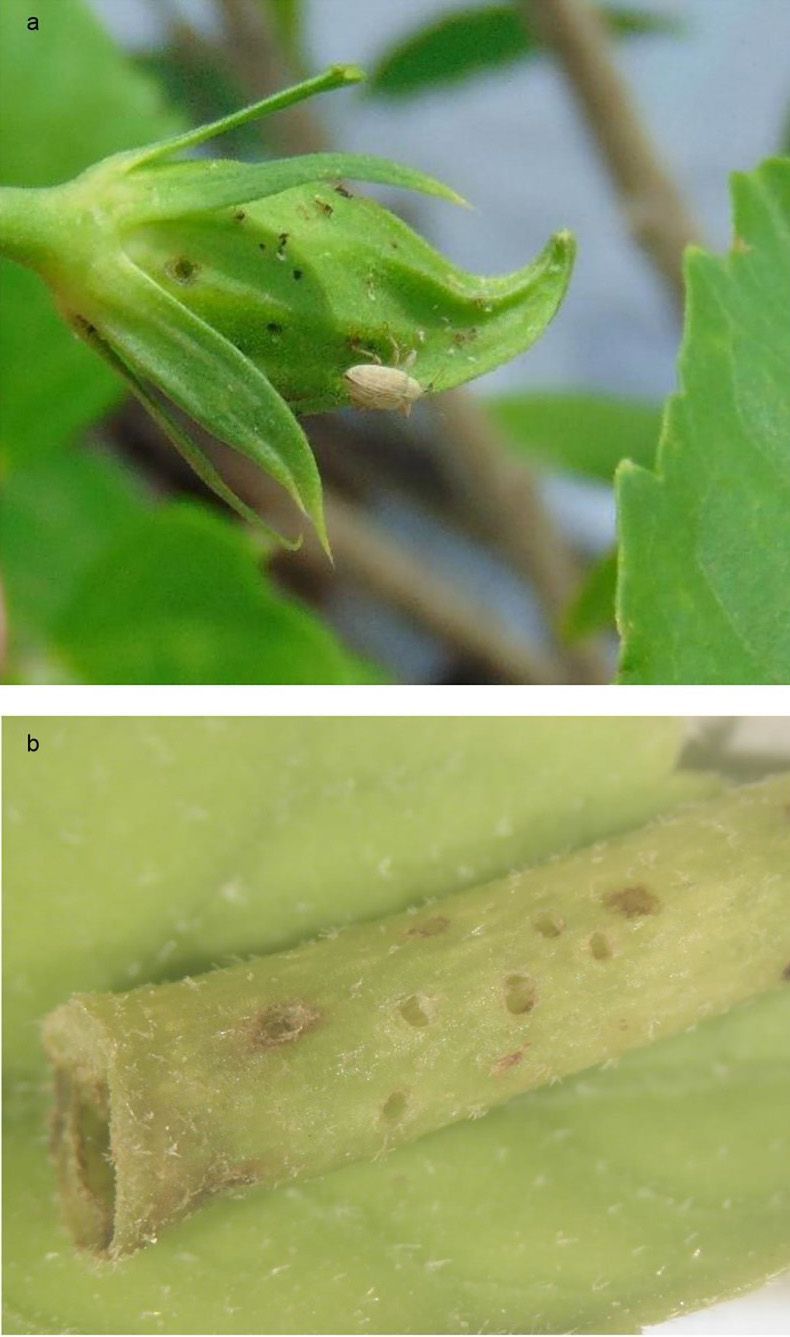

Adult weevils feed primarily on hibiscus buds, stems, and, to a lesser extent, on the leaves. The females oviposit in flower buds, and larvae develop inside the bud, causing bud drop prior to flowering. Infestation symptoms include holes in stems and unopened buds (Figure 7) and severe bud drop when weevil densities are high. Hibiscus bud weevil infestation has been associated with a 16-fold increase in flower bud abortion compared to non-infested plants (Vargas et al. 2024). Feeding damage on the leaves is not apparent. In south Florida nurseries, pink and yellow hibiscus varieties appear to be the most susceptible to hibiscus bud weevil (Table 2). More specifically, the pink variety ‘Painted Lady’ and the yellow variety ‘Sunny Yellow’ are reported to be the most susceptible varieties. The red variety ‘President Red’ is reported to be the most tolerant to hibiscus bud weevil.

Table 2. Hibiscus varieties cultivated in Florida that have been found infested with the hibiscus bud weevil (Anthonomus testaceosquamosus Linell).

Credit: Juleysy Rodriguez and Yisell Velazquez-Hernandez, UF/IFAS TREC

Another pest causing hibiscus flower bud drop is the hibiscus bud midge (Contarinia maculipennis, Diptera: Cecidomyiidae), which can be mistaken for hibiscus bud weevil damage (Mannion et al. 2006). Both pests can infest the same hibiscus plant; however, they will rarely infest the same flower bud. Buds infested with the hibiscus bud midge will have multiple white to yellow maggots (larvae) inside them that jump when disturbed. Midge maggots lack a head and legs and need to exit the bud to pupate in the soil while the weevil larvae have true heads and pupate within the buds (Figure 8; Figure 9).

Credit: Juleysy Rodriguez and Yisell Velazquez-Hernandez, UF/IFAS TREC

Credit: Juleysy Rodriguez and Yisell Velazquez-Hernandez, UF/IFAS TREC

Biology

Adult female weevils deposit 3–5 eggs into a single hibiscus flower bud close to the anthers (Figure 5). Emerged larvae feed on pollen and remain in the flower bud until they reach adulthood. Due to the high incidence of larval cannibalism, not all eggs will successfully develop into an adult weevil; however, multiple weevils may exit one flower bud. At 27°C (80.6°F), eggs hatch within 2–3 days of oviposition. The larval stage has three instars and can last, on average, 10 days. The pupal stage (Figure 10) lasts 2.9–4.2 days. Development from egg to adult can range from 12.8–16.3 days, and survival has been observed up to 90%. Adult longevity ranges from 13–169 days, with the males living longer than the females. When fed solely on pollen, adults can survive up to 52 days. Adult weevils can survive on an average for 28 days without food when they have access to water, and 16 days without water. The sex ratio is 1:1 females to males (Revynthi et al. 2022). Preliminary research has shown that the hibiscus bud weevil can also complete its life cycle on okra flower buds (Abelmoschus esculentus).

Credit: Juleysy Rodriguez and Yisell Velazquez-Hernandez, UF/IFAS TREC

Very low (<10°C or 50°F) or high (>35°C or 95°F) temperatures appear to be detrimental to the development of this weevil. In laboratory experiments at the University of Florida, at 10°C (50°F) no eggs hatched, while at 15°C (59°F) eggs hatched 12 days after oviposition, but the larvae did not feed and eventually died. Similarly, at 34°C (93.2°F), eggs hatched within 5.5 days, but none of the larvae managed to pupate. In south Florida, the peak activity of this weevil has been observed from March through June (23°C –28°C or 73.4°F –82.4°F) with lower populations from September until February (22°C –28°C or 71.6°F –82.4°F). Based on this information and high dependence on the hibiscus plant, the weevil is expected to be limited to tropical and subtropical areas with large hibiscus production.

Development of Pest Management and Monitoring Techniques

Integrated pest management programs targeting the hibiscus bud weevil should involve a combination of cultural practices, sanitation, active monitoring, chemical intervention, and biological control. Implementing a combination of these practices will reduce reliance on insecticide inputs for plant protection.

Cultural Practices

Crop rotation with non-host species has been recommended for interrupting population cycles by removing host plant material and insect reservoirs within production settings (Bográn et al. 2003). Sanitation includes systematic collection and destruction of all dropped buds from the ground. Although sanitation is labor-intensive, it has been proposed as the most efficient management practice against this weevil since dropped buds contain weevils that will continue to infest new plants (Bográn et al. 2003). A weekly collection of dropped buds resulted in a 22% reduction in the proportion of dropped buds in comparison to plants where no sanitation was implemented (Vargas et al. 2024). The most time-efficient method to implement sanitation is to use a vacuum (Vargas et al. 2024).

Chemical Control

Contact-toxic insecticides target the adult weevils that live freely on the hibiscus plant canopy, while systemic insecticides target the developing hibiscus bud weevil larvae inside the flower buds. Laboratory and greenhouse experiments evaluating the efficacy of contact-toxic insecticides showed that diflubenzuron (Dimilin® 25W, 16 oz/acre, IRAC group15, ohp); pyrethrins (PyGanic Crop Protection® EC, 15.61 fl oz/acre, IRAC group 3A, Valent); spinetoram plus sulfoxaflor (Xxpire®, 2.75 oz/acre, IRAC group 4C+5, Corteva); and spirotetramat (Kontos®, 3.4 fl oz/acre, IRAC group 23, Envu) provided the highest level of control . Moreover, mineral oils (Ultra-fine®, 2%, unknown IRAC group, HollyFrontier and Suffoil-X®, 2%, unknown IRAC group, BioWorks) can also be effective contact insecticides targeting adult weevils (Greene et al. 2023). Applications of the non-neonicotinoid systemic insecticides chlorantraniliprole (Acelepryin®, 16 fl oz/acre, IRAC group 28, Syngenta); flupyradifurone (Altus®, 28 fl oz/acre, IRAC group 4D, Envu); and cyantraniliprole (Mainspring®, 12 fl oz/acre, IRAC group 28, Syngenta) one month before a hibiscus infestation limited weevil feeding and oviposition activity and reduced larval survival (Vargas et al. 2023).

Biological Control

Biological control using entomopathogenic nematodes can offer a sustainable and environmentally friendly solution for managing the hibiscus bud weevil. Foliar spray applications of Steinernema carpocapsae resulted in significant weevil larval mortality within hibiscus flower buds. In addition, this foliar spray nematode application can also control weevil larvae in hibiscus flower buds that have fallen to the soil surface beneath potted plantings (Vargas et al. 2024). Entomopathogenic fungi and bacteria can be used to target adult hibiscus bud weevils. Research shows that the fungus Beauveria bassiana and the bacterium Chromobacterium subtsugae have the potential to reduce weevil reproduction and feeding. Recently, a polyphagous ectoparasitoid wasp, Catolaccus hunteri Crawford (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae), became available in the American commercial biological control market. This tiny wasp parasitizes closely related pest weevils, the cotton boll weevil and the pepper weevil (Vazquez 2004; Gomez-Dominguez et al. 2012). Preliminary studies have shown that Catolaccus hunteri can also parasitize hibiscus bud weevil larvae, warranting further research.

Pest Monitoring Tools

Pheromone traps broadly used for other Anthonomus species are being explored as a pest-monitoring tool. Several species within the Anthonomus genus are attracted to a group of commercial lures that contain male aggregation pheromones and host plant volatiles that are attractive to adult weevils (Tumlinson et al. 1969; Eller et al. 1994; Innocenzi et al. 2001). There are four components of the synthetic male aggregation pheromone, also known as Grandlures I–IV. In Texas, cotton boll weevil pheromone traps were evaluated and determined to not successfully attract hibiscus bud weevil adults, although this requires further investigation (Bográn et al. 2003). Yellow sticky traps are the most attractive traps for several Anthonomus species, including the hibiscus bud weevil (Cross et al. 2006; Szendrei et al. 2011; Silva et al. 2018; Ataide et al. 2024). Trials conducted to test hibiscus bud weevil attraction to lures for boll, pepper, and cranberry weevils (Anthonomus musculus) showed that yellow sticky cards with the cranberry weevil lure placed at canopy height caught the largest number of adult hibiscus bud weevils (Ataide et al. 2024).

The best way to manage the hibiscus bud weevil in Florida and decrease the economic damage it causes is to use an IPM program implementing all of the strategies described above. Monitor hibiscus crops each week to detect weevils early. Sanitize to break the weevil population cycle by collecting and destroying dropped hibiscus buds at least twice per month throughout the hibiscus growing season (August–March). When weevil populations are low (August–February), employ biological control agents such as entomopathogenic nematodes, fungi, or bacteria to help keep populations under control, reducing the need for contact insecticide applications. As the plants grow and produce more flower buds (around February), systemic insecticide applications can offer protection from increasing weevil populations. As the shipping season approaches (March–May), to comply with existing regulations, contact insecticides may be applied to ensure effective control and production of clean plant material.

References

Ataide, L. M. S., A. D. Greene, K. R. Cloonan, et al. 2024. “Exploring Market-Available Pheromone Lures and Traps for Monitoring Anthonomus testaceosquamosus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae).” Journal of Economic Entomology 117 (10): 1396–1405. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toae105

Bográn, C. E., K. M. Heinz, and S. Ludwig. 2003. “The Bud Weevil Anthonomus testaceosquamosus, a Pest of Tropical Hibiscus.” In: SNA Research Conference Entomology. pp 147–149.

Capinera, J. L. 2002. "Pepper Weevil Anthonomus eugenii Cano (Insecta: Coleoptera: Curculionidae)." EENY-278. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN555

Clark, W. E., H. R. Burke, R. W. Jones, and R. S. Anderson. 2019. “The North American Species of the Anthonomus squamosus Species-Group (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Curculioninae: Anthonomini).” Coleopterists Bulletin 73 (4): 773. https://doi.org/10.1649/0010-065X-73.4.773

Cortez-Mondaca, E., N. M. Bárcenas-Ortega, J. L Martínez-Carrillo, et al. 2004. “Parasitismo de Catolaccus grandis y Catolaccus hunteri (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae) Sobre el Picudo del Algodonero (Anthonomus grandis Boheman).” Agrociencia 38 (5): 497–501.

Cross, J. V., H. Hesketh, C. N. Jay, et al. 2006. “Exploiting the Aggregation Pheromone of Strawberry Blossom Weevil Anthonomus rubi Herbst (Coleoptera: Curculionidae): Part 1. Development of Lure and Trap.” Crop Protection 25:144–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2005.04.002

Eller, F. J., R. J. Bartelt, B. S. Shasha, et al. 1994. “Aggregation Pheromone for the Pepper Weevil, Anthonomus eugenii Cano (Coleoptera: Curculionidae): Identification and Field Activity.” Journal of Chemical Ecology 20:1537–1555. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02059879

Gomez-Dominguez, N. S., R. J. Lomeli-Flores, E. Rodriguez-Leyva, J. M. Valdez-Carrasco, and A. Torres-Ruiz. 2012. “Ovipositor of Catolaccus hunteri Burks (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae) and Implications for its Potential as a Biological Control Agent of Pepper Weevil.” Southwestern Entomologist 37 (2): 239–242 https://doi.org/10.3958/059.037.0218

Greene, A. D., X. Yang, Y. Velazquez-Hernandez, et al. 2023. “Lethal and Sublethal Effects of Contact Insecticides and Horticultural Oils on the Hibiscus Bud Weevil, Anthonomus testaceosquamosus Linell (Coleoptera: Curculionidae).” Insects 14 (6): 544. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects14060544

Hunsberger, A., J. E. Pena, R. M. Giblin-Davis, G. Gries, and R. Gries. 1998. “Biodynamics of Anthonomus macromalus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), a Weevil Pest of Barbados Cherry in Florida.” Florida State Horticultural Society 111:334–338.

Innocenzi, P. J., D. R. Hall, and J. V. Cross. 2001. “Components of Male Aggregation Pheromone of Strawberry Blossom Weevil, Anthonomus rubi Herbst. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae).” Journal of Chemical Ecology 27:1203–1218. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010320130073

Loiácono, M. S., A. E. Marvaldi, and A. A. Lanteri. 2003. “Description of Larva and New Host Plants for Anthonomus rubricosus Boheman (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in Argentina.” Entomological News 114:69–74.

Mannion, C., A. Hunsberger, K. Gabel, E. Buss, and L. Buss. 2006. Hibiscus bud midge (Contarinia maculipennis). UF/IFAS Extension. http://trec.ifas.ufl.edu/mannion/pdfs/HibiscusMidge.pdf (no longer available online).

Revynthi, A. M., Y. V. Hernandez, M. A. Canon, et al. 2022. “Biology of Anthonomus testaceosquamosus Linell, 1897 (Coleoptera: Curculionidae): A New Pest of Tropical Hibiscus.” Insects 13 (1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13010013

Silva, D., J. Salamanca, V. Kyryczenko-Roth, et al. 2018. “Comparison of Trap Types, Placement, and Colors for Monitoring Anthonomus musculus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) Adults in Highbush Blueberries.” Journal of Insect Science 18 (2): 19; 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/jisesa/iey005

Skelley, P. E., and L. S. Osborne. 2018. Pest Alert Anthonomus testaceosquamosus Linell, the Hibiscus Bud Weevil, New in Florida. FDACS-P-01553. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Division of Plant Industry

Szendrei, Z., A. Averill, H. Alborn, and C. Rodriguez-Saona. 2011. “Identification and Field Evaluation of Attractants for the Cranberry Weevil, Anthonomus musculus Say.” Journal of Chemical Ecology 37:387–397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-011-9938-z

Tumlinson, J. H., D. D. Hardee, R. C. Gueldner, et al. 1969. “Sex Pheromones Produced by Male Boll Weevil: Isolation, Identification, and Synthesis.” Science 166 (3908): 1010–1012. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.166.3908.1010

United States Department of Agriculture. 2022. “Table 2. Market Value of Agricultural Products Sold Including Food Marketing Practices and Value-Added Products: 2022 and 2017” In the 2022 Census of Agriculture Volume 1, Chapter 2: State Level Data https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2022/Full_Report/Volume_1,_Chapter_2_US_State_Level/

Vargas, G., A. D. Greene, Y. Velazquez-Hernandez, et al. 2023. “A Prophylactic Application of Systemic Insecticides Contributes to the Management of the Hibiscus Bud Weevil Anthonomus testaceosquamosus Linell (Coleoptera: Curculionidae).” Agriculture 13 (10): 1879. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13101879

Vargas, G., A. Daniel Greene, Y. Velazquez-Hernandez, et al. 2024. “Implementing Sanitation Practices Against the Hibiscus Bud Weevil Anthonomus testaceosquamosus Linell (Coleoptera: Curculionidae).” Florida Entomologist 107 (1) 2024, pp. 20240023. https://doi.org/10.1515/flaent-2024-0023

Vargas, G., Y. Velazquez-Hernandez, A. Daniel Greene, et al. 2024. “Entomopathogenic Nematodes to Control the Hibiscus Bud Weevil Anthonomus testaceosquamosus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), Above Ground and on Soil Surface.” BioControl 69:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-024-10242-9