The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

The rednecked peanutworm, Stegasta bosqueella (Chambers) (Figure 1), is a visually unique caterpillar that personifies its common name. It is widespread in peanut fields across the United States and is considered a major pest in other peanut producing regions of the world. Late instar larvae are very active and can be found on exposed open leaves prior to pupating, but more often only feeding injury is observed for this caterpillar. The rednecked peanutworm feeds within the terminals (new unopened leaves) of the host plant and tends to be difficult to find as a result.

Credit: Barry Tillman, University of Florida

Synonymy

Stegasta bosqueella is accepted as the current scientific name for this insect and the rednecked peanutworm is recognized as the approved common name (ESA Common Name Database). Over time, several synonyms have been used for Stegasta bosqueella; some were even used by Chambers himself (adding to uncertainty). Confusion regarding the scientific name has led to inconsistent spelling in the literature. In April 2020, Pinto et al. (2020) reported 206 scientific publications using Stegasta bosquella (incorrect name) and 105 using Stegasta bosqueella (correct name) found on Google Scholar from 1946 to 2020. Known synonyms include:

- Stegasta bosquella Chambers, 1878

- Stegasta basquella Möschler, 1890

- Parastega bosqueella Walsingham, 1897

- Parastega basqueella Busck, 1903

- Gelechia basqueella Meyrick, 1904

- Gelechia costipunctella Bondar, 1928

- Red-necked peanut worm

- Red-necked peanutworm

- Rednecked peanut worm

Distribution

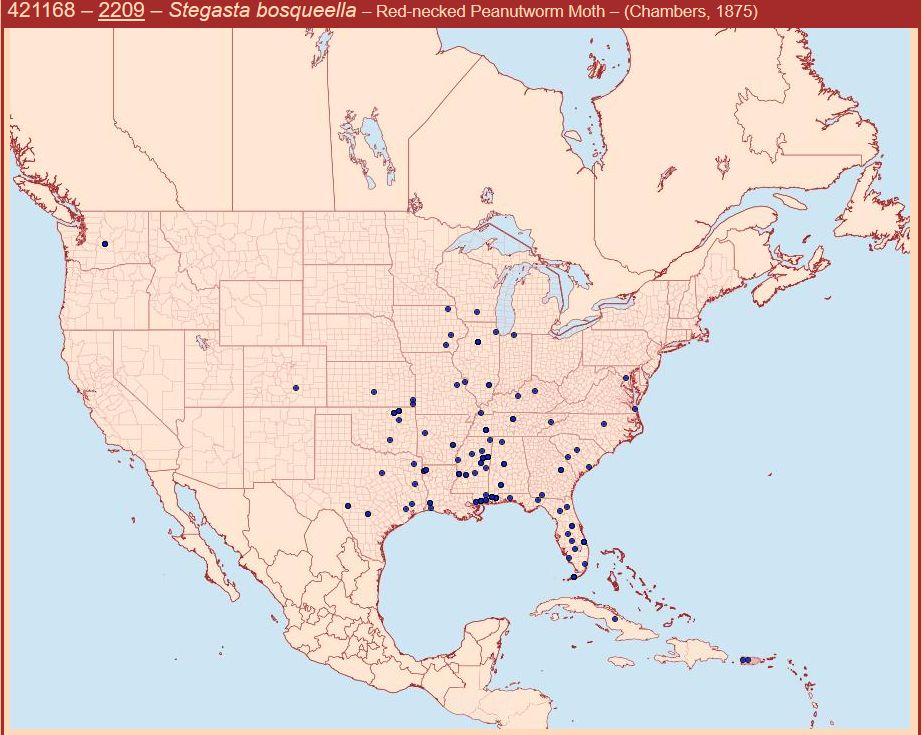

The rednecked peanutworm is a cosmopolitan pest associated with peanut production. It has been recorded in the United States, Mexico, Central and South America, Australia, Africa, and North Korea (Pinto et al. 2020). Native to Florida, Stegasta bosqueella is a common occurrence in peanut fields and is documented as the most common foliage feeder of peanut in other states (Heppner 2003, Mulder and Berberet 2004). The known distribution of Stegasta bosqueella across the United States, Cuba, and Puerto Rico is shown in Figure 2.

Credit: Used with permission and created by the Moth Photographers Group at the Mississippi Entomological Museum at Mississippi State University

Although the rednecked peanutworm is found throughout the growing season, populations tend to be highest mid to late season in Florida; this is typically from July through August (Arthur et al. 1959).

Description and Life Cycle

Different numbers of generations per year have been reported from various locations and studies (temperature likely an influencing factor), but all agree multiple generations occur. At least two generations have been reported in Alabama and three in Oklahoma (Arthur et al. 1959, Wall and Berberet 1980). During late July and August, the life cycle of Stegasta bosqueella may be completed in as few as 23 days (Wall and Berberet 1980).

Eggs

Stegasta bosqueella females deposit eggs singly or in small groups along plant stems near terminal buds. The eggs are small and slightly elongated in shape, measuring ~0.20 to 0.30 mm in length (Pinto et al. 2020). Initially white, they slowly change to a pale yellow or cream color as the embryo develops and hatching nears. One study found that it took approximately 5.3 days for eggs to hatch at 75°F (24°C), while another study documented 2 to 3 days hatch time at an average of 77°F (25°C) (Wall and Berberet 1980, Pinto et al. 2020).

Larvae

Larvae are white to yellowish cream in color and have black spiracles and a red band around the two body segments just posterior to the dark head capsule (Figure 3). Due to the difficulty of observing larvae when they are feeding in plant terminals, there is little information available regarding different instars and their duration under field conditions.

Credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS Entomology and Nematology Department

In a laboratory study, Pinto et al. (2020) documented five instars and the size range for each. First instar larvae ranged 0.75 to 1.0 mm, second instars approximately 2 mm, third instars 3.5 mm, fourth instars approximately 5 mm, and fifth instars approximately 7 mm. It was also noted that the prothorax and mesothorax of the first instar lacked the reddish color, while all other instars exhibited this distinctive coloration. The larval stage is completed in eight to 15 days (Wall and Berberet 1980, Pinto et al. 2020).

Pupae

Prior to pupation, larvae suspend feeding and actively search for a pupation site. Pupation occurs in either the plant terminals or upper 5 mm of soil around the base of the plant (Arthur et al. 1959, Wall and Berberet 1980). Pupae measure 5 to 8 mm in length, and color ranges from light to dark brown prior to emergence (Pinot et al. 2020). Duration of the pupal stage ranges four to ten days (Wall and Berberet 1980, Pinto et al. 2020).

Adults

Similar to the larval stage, the adult stage of Stegasta bosqueella is very striking in appearance (Figure 4). A small, colorful moth, it can measure from 5 to 12 mm in length (Bissell 1942, Manley 1961).

Credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS Entomology and Nematology Department

It is dominantly brown to black in color, with a large irregular yellowish-orange to tan spot at the base of the wings (Bissell 1942, Pinto et al. 2020). Prominent white marks are found on the wings, as well as yellowish-tan bands on the legs. Under laboratory conditions, adults were found to live six to 16 days (Manley 1961). Sexual dimorphism is observed in adults; males exclusively bear a median dorsal tuft of scales on the apex of the abdomen (Manley 1961, Pinto et al. 2020).

Hosts

The major host of Stegasta bosqueella is peanut (Figure 5). Most but not all its host plants are legume crops and other plants in the Fabaceae family. These include alfalfa, cowpea, soybean, partridge pea, blue wild indigo, hairy vetch, and prairie acacia. It has also been documented on flower buds of Zornia and Stylosanthes spp. (both Fabaceae) as well as the axils of pineapple (Bromeliaceae) leaves (Pinto et al. 2020).

Credit: Ethan Carter, University of Florida

Damage and Economic Importance

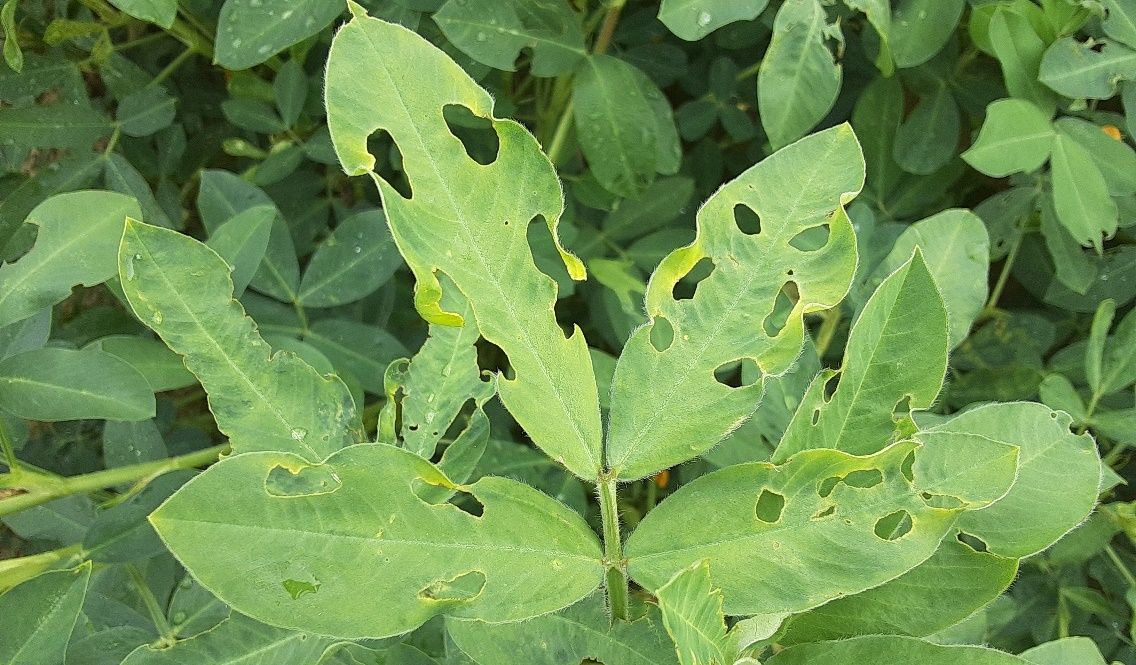

Despite its common name and frequent occurrence in peanut fields, the rednecked peanutworm is seldom an economic pest in the United States, and control is only recommended when damage is excessive (Bissell 1942, Lemon 2001, Alabama Cooperative Extension 2020). Generally thought of as a cosmetic pest in Florida, it does not defoliate a peanut crop like other caterpillars. The preferred feeding location in plant terminals often results in a tattered appearance that is easily visible and alerts producers to the caterpillar’s presence. Although Stegasta bosqueella is not viewed as an economic pest in the United States, it is the dominant pest of peanut fields in South and Central America (Pinto et al. 2020). It is currently recognized as the most important lepidopteran pest of peanut in Brazil (Rivero et al. 2017). Due to the feeding habit of the rednecked peanutworm, injury is localized to plant terminals and occurs prior to the unfolding of new leaves. As a result, leaf injury is often not visible until after the leaves open (Figures 6 and 7).

Credit: Ethan Carter, University of Florida

Credit: Ethan Carter, University of Florida

Leaf damage caused by Stegasta bosqueella is typically distinguished from that of other foliage feeding caterpillars by telltale symmetrical holes in the plant leaves versus injury along leaf margins or only one leaflet (Figure 7).

Management

Insecticide applications specifically for this insect are usually not recommended unless populations are extremely high in plant terminals or there is a mixed population with other damaging caterpillar pests in the field (Lemon 2001, Mulder and Berberet 2004). Most commercial peanut acreage in the southeastern United States usually receives a few maintenance insecticide applications mixed with the scheduled fungicide applications which may help keep rednecked peanutworm populations manageable. A study in Alabama found reductions in rednecked peanutworm populations in treated plants compared to untreated but did not observe a significant yield increase from the treatments (Arthur et al. 1959). Chemical insecticides are also the main method of control for the rednecked peanutworm in Central and South America. Evaluations performed across North, Central, and South America have found that contact insecticides are not as effective for controlling the rednecked peanutworm as broad-spectrum systemic insecticides (Pinot et al. 2020). Contact insecticides are not as effective due to the larval stage feeding predominantly in closed peanut terminals versus on an open leaf where the insecticide can reach them.

Selected References

Alabama Cooperative Extension. (2020). Peanut IPM Guide. IPM-0360. Alabama A&M and Auburn Universities. (10 August 2020).

Arthur BW, Hyche LL, Mount RH. 1959. Control of the red-necked peanutworm on peanuts. Journal of Economic Entomology 52: 468-470.

Bissell TL. 1942. A micro leaf worm on peanuts. Journal of Economic Entomology 35:104-104.

Heppner JB. 2003. Arthropods of Florida and Neighboring Land Areas: Lepidoptera of Florida. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services 17: 1-670.

Lemon R. (2001). Insect issues in peanuts. Texas Cooperative Extension. (10 August 2020)

Manley CV. 1961. The biology of Stegasta bosqueella (Chambers) (Lepidoptera, Gelechiidae). Ph.D. dissertation. Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK.

Mulder P, Berberet RC. (2004). Peanut insect control in Oklahoma.CR-7174. Oklahoma State University. (10 August 2020)

Pinto JRL, Boica AL, Fernandes OA. 2020. Biology, ecology, and management of rednecked peanutworm (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Journal of Integrated Pest Management 11: 1-15.

Rivero YR, Andrade DJ, Santos FA, Melville CC, Leite GWP. 2017. New attractant food for catching adult rednecked peanutworm (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) in peanut. Florida Entomologist 100: 660-662.

Wall RG, Berberet RC. 1980. Thermal requirements for development of the rednecked peanutworm, Stegasta Bosqueella. Peanut Science 7: 72-72.