The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

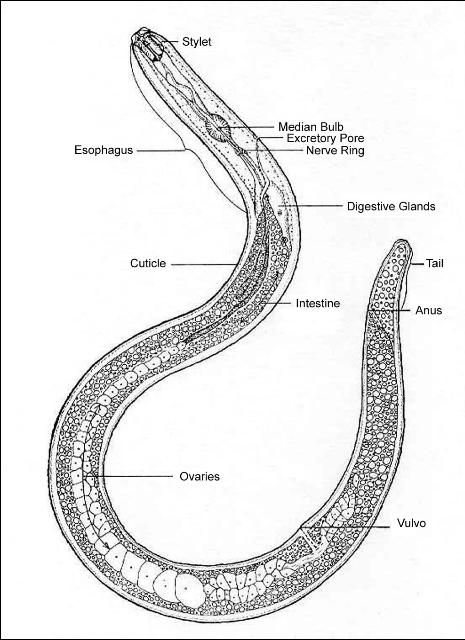

Nematodes (Figure 1) are found in almost all habitats, but are often overlooked because most of them are microscopic in size. For instance, a square yard of woodland or agricultural habitat may contain several million nematodes. Many species are highly specialized parasites of vertebrates, including humans, or of insects and other invertebrates. Other kinds are plant parasites, some of which can cause economic damage to cultivated plants. Nematodes are particularly abundant in marine, freshwater, and soil habitats. One study in Colorado estimated that nematodes consumed about as much grass as a prairie dog colony.

Credit: UF/IFAS

Soil Nematodes

Soil is an excellent habitat for nematodes, and 100 cc of soil may contain several thousand of them. Because of their importance to agriculture, much more is known about plant-parasitic nematodes than about the other kinds of nematodes which are present in soil. Most kinds of soil nematodes do not parasitize plants, but are beneficial in the decomposition of organic matter. These nematodes are often referred to as free-living nematodes. Juvenile or other stages of animal and insect parasites may also be found in soil. Although some plant parasites may live within plant roots, most nematodes inhabit the thin film of moisture around soil particles. The rhizosphere soil around small plant roots and root hairs is a particularly rich habitat for many kinds of nematodes.

Classification

Nematodes are roundworms in the Phylum Nematoda. Various authorities distinguish among 16 to 20 different orders within this phylum. Only about 10 of these orders regularly occur in soil, and four orders (Rhabditida, Tylenchida, Aphelenchida, and Dorylaimida) are particularly common in soil.

More than 15,000 species and 2,200 genera of nematodes had been described by the mid-1980s. Although the plant-parasitic nematodes are relatively well-known, most of the free-living nematodes have not been studied very much. Therefore there is a high probability that most soil habitats will contain undescribed species of free-living nematodes. Identification of these groups is extremely difficult, and there are only a few nematode taxonomists in the world who can formally describe new species of free-living nematodes to science. Therefore most nematode ecologists identify soil nematodes only to family or genus.

Feeding Habits

Soil-inhabiting nematodes can also be classified according to their feeding habits. This classification is particularly useful to ecologists in understanding the positions of nematodes in soil food webs. Several important feeding groups of nematodes commonly occur in most soils. In addition, algivores (feed on algae) and various stages of insect and animal parasites occasionally are found in soil. The nematode feeding groups are called trophic groups by some authors.

Herbivores

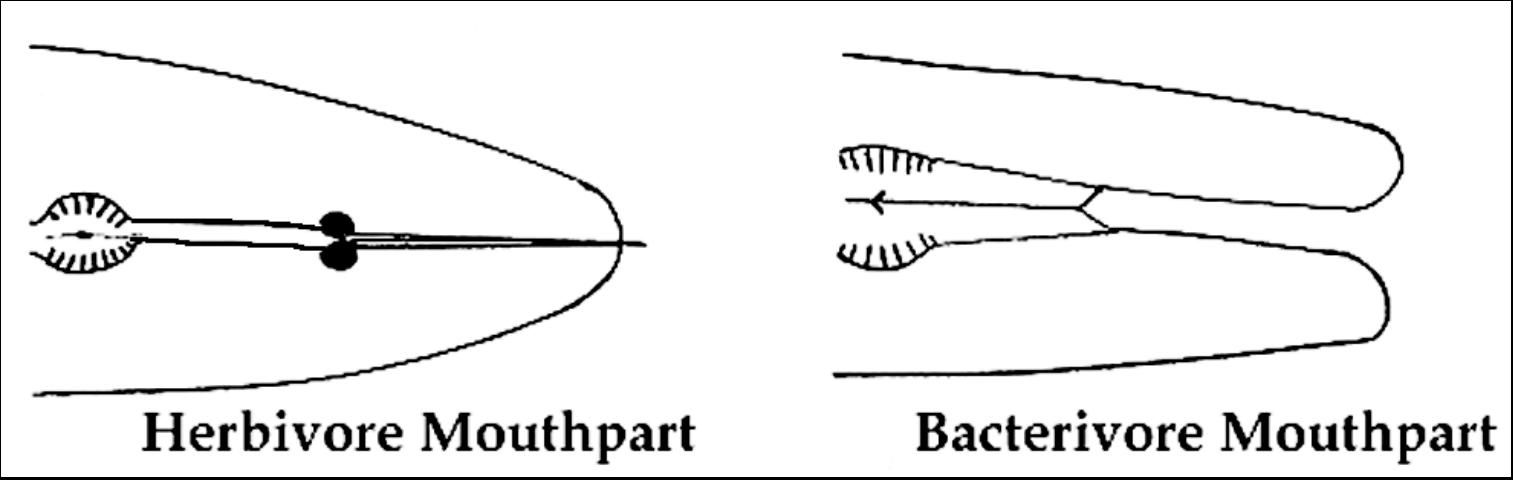

These are the plant parasites, which are relatively well known. This group includes many members of the order Tylenchida, as well as a few genera in the orders Aphelenchida and Dorylaimida. The mouthpart (Figure 2) is a needlelike stylet which is used to puncture cells during feeding. Ectoparasites remain in the soil and feed at the root surface. Endoparasites enter roots and can live and feed within the root.

Credit: UF/IFAS

Bacterivores

Many kinds of free-living nematodes feed only on bacteria, which are always extremely abundant in soil. In these nematodes, the "mouth", or stoma, is a hollow tube (Figure 2) for ingestion of bacteria. This group includes many members of the order Rhabditida as well as several other orders which are encountered less often. These nematodes are beneficial in the decomposition of organic matter.

Fungivores

This group of nematodes feeds on fungi and uses a stylet to puncture fungal hyphae. Many members of the order Aphelenchida are in this group. Like the bacterivores, fungivores are very important in decomposition.

Predators

These nematodes feed on other soil nematodes and on other animals of comparable size. They feed indiscriminately on both plant parasitic and free-living nematodes. One order of nematodes, the Mononchida, is exclusively predacious, although a few predators are also found in the Dorylaimida and some other orders. Compared to the other groups of nematodes, predators are not common, but some of them can be found in most soils.

Omnivores

The food habits of most nematodes in soil are relatively specific. For example, bacterivores feed only on bacteria and never on plant roots, and the opposite is true for plant parasites. A few kinds of nematodes may feed on more than one type of food material, and therefore are considered omnivores. For example, some nematodes may ingest fungal spores as well as bacteria. Some members of the order Dorylaimida may feed on fungi, algae, and other animals.

Unknown

Since free-living nematodes have not been studied very much, the food habits of some of them are unknown. The microscopic size of these animals presents additional difficulties. For example, it can be very difficult to distinguish whether a nematode is feeding on dead cells from a plant root or on fungi growing on the cell surface. Sometimes a nematode showing this feeding behavior may be classified simply as a root or plant associate.

Community Composition

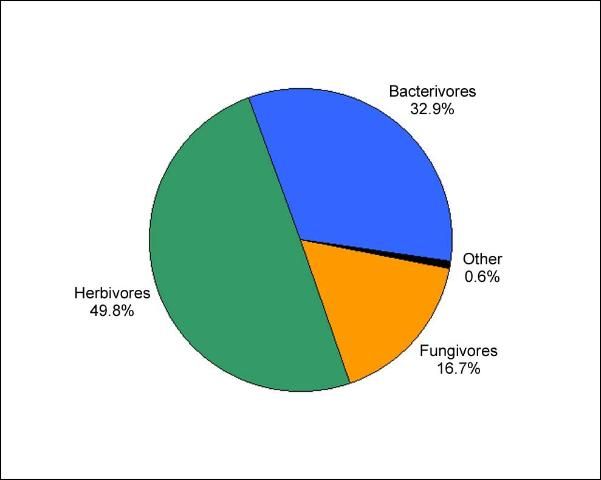

In one pasture in south-central Florida, herbivores comprised almost half of the soil nematode community, but bacterivores and fungivores were also well-represented (Figure 3). This habitat provided many fibrous roots as a food source for herbivores, but other nematode groups, particularly bacterivores, may predominate in other habitats. The composition of the soil nematode community depends on the vegetation present, as well as on soil type, season, soil moisture level, amount of soil organic matter, and many other factors. Because they are responsive to so many different factors, it is believed that nematodes may be useful bioindicators of the condition of the soil environment.

Credit: UF/IFAS

Decomposition

Free-living nematodes are very important and beneficial in the decomposition of organic material and the recycling of nutrients in soil. Nematode bacterivores and fungivores do not feed directly on soil organic matter, but on the bacteria and fungi which decompose organic matter. The presence and feeding of these nematodes accelerate the decomposition process. Their feeding recycles minerals and other nutrients from bacteria, fungi, and other substrates and returns them to the soil where they are accessible to plant roots.

Management

Selected References

Freckman, D.W. 1982. Nematodes in Soil Ecosystems. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

Ingham, R.E., and J.K. Detling. 1984. Plant-herbivore interactions in a North American mixed-grass prairie. III. Soil nematode populations and root biomass on Cynomys ludovicianus colonies and adjacent uncolonized areas. Oecologia 63: 307-313.

McSorley, R., J. . Federick. 2000. Short-term effects of cattle grazing on nematode communities in Florida Pastures. Nematropica 30: 211-211.

Poinar, G.O., Jr. 1983. The Natural History of Nematodes. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Wallace, H.R. 1973. Nematode Ecology and Plant Disease. Edward Arnold, London, UK.

Wang, K-H, R. McSorley, T.R. Fasulo. 2006. Foliar and Root-knot Nematodes as Pests of Ornamental Plants. Bug Tutorials. Univeristy of Florida/IFAS. CD-ROM. SW-188.

Wharton, D.A. 1986. A Functional Biology of Nematodes. Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, MD.

Yeates, G.W., T. Bongers, R.G. . de Goede, D.W. Freckman, and S.S. Georgieva. 1993. Feeding habits in soil nematode families and genera- an outline for soil ecologists. J. Nematol. 25:315-331.