Introduction

Blueberry production in Florida has expanded over the past 20 years, with Florida ranking eighth in the country (Phillips et al 2021). In 2022, the USDA State Agricultural Overview estimated that the value of production for blueberry farms in Florida was over $84.2 million. Flatheaded borers have caused considerable economic damage to a variety of nursery plants, trees, and agricultural crops in North America (Addesso 2021).

Flatheaded borers are emerging pests for nursery plants, fruit crops, hardwood trees, and tree nut orchards (Rudolph and Wiman 2023). Various species from the genus Chrysobothris native to Florida have become important agricultural pests, especially in highbush blueberries. The flatheaded appletree borer, Chrysobothris femorata (Olivier), is a wood-boring jewel beetle that is the primary species found to be causing extensive damage to blueberry plants. Another jewel beetle species of concern in Florida is Chrysobothris chrysoela (Illiger) (Figure 1).

These two Chrysobothris species were first recorded in blueberries in Florida during the 2014 growing season, when growers found infested blueberry plantings. In 2016, the Small Fruit and Vegetable IPM Laboratory at the University of Florida recovered larvae from samples in southern highbush blueberries (Spies 2018). Ongoing studies in Florida have found their presence in the field and damage due to these native Chrysobothris species are becoming more prominent. The main purpose of this article is to provide information on specific flatheaded borer species that may be contributing to damage to blueberry fields and plants. This information is intended for use by extension agents, growers, and interested laypersons.

Credit: Alexis Zapata and Lyle Buss

Distribution and Seasonality

The range of flatheaded appletree borers extends throughout North America from Canada to the United States and Mexico (Wellso and Manley 2007). Within the state of Florida, observations and captures of C. femorata and C. chrysoela in blueberries have been recorded primarily in north and central Florida.

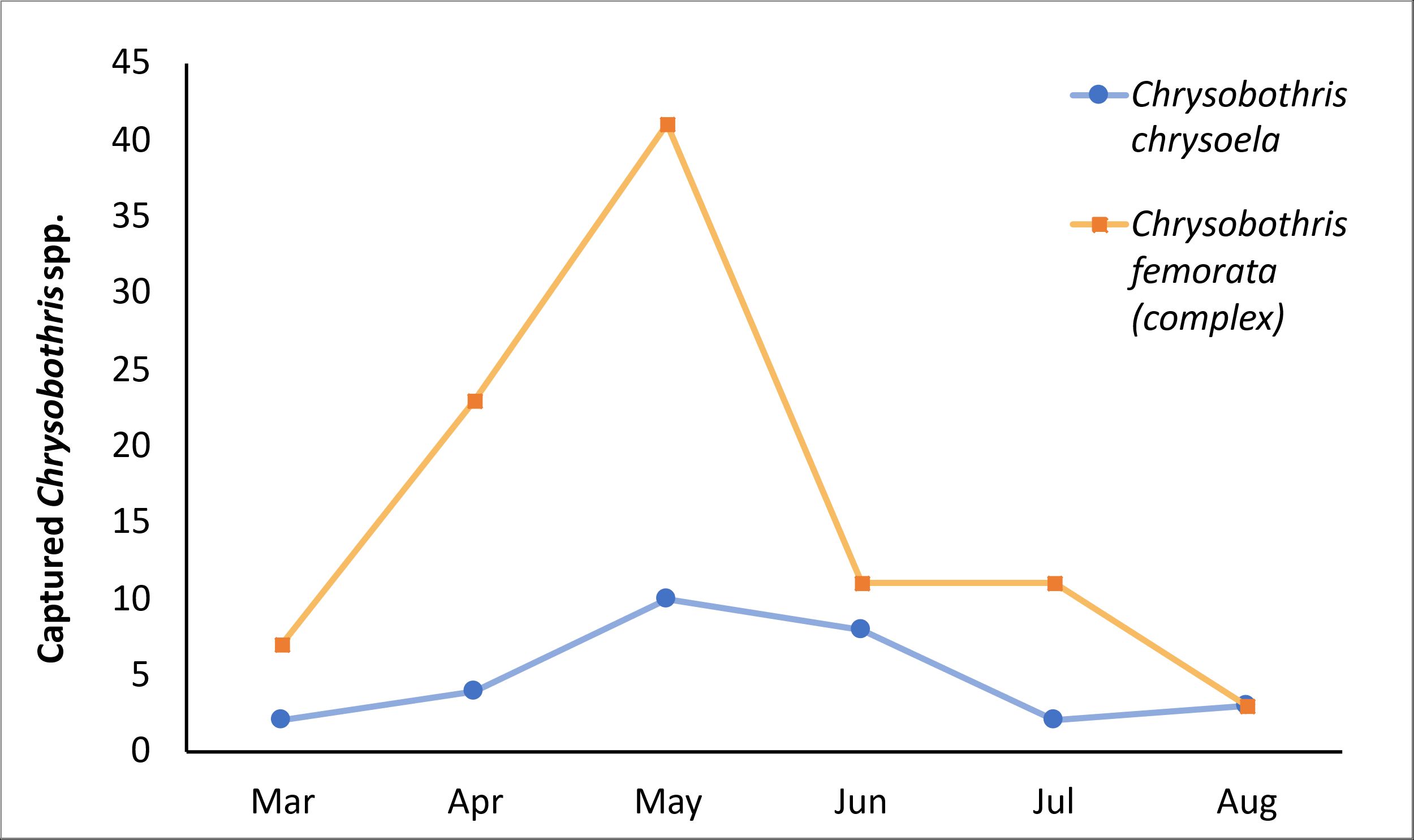

Adult Chrysobothris species in Florida are present on blueberry farms from early March to late August. Population pressure of both species peak primarily from mid-April to mid-May (Figure 2). In instances where warm weather is prolonged, flatheaded borers may appear sporadically on traps until October, specifically species such as Acmaeodera pulchella and Acmaeodera tubulus. Further work is needed to fully understand the full extent of these pest species throughout the state.

Credit: Small Fruit and Vegetable IPM Lab at the University of Florida

Biology

Eggs, Larvae, and Pupae

The eggs of Chrysobothris species are laid in crevices on the bark such as under peeled portions of the outer bark. The eggs incubate for an average of 15–20 days (Williamson 2023). The larvae then feed on the inner bark of the host plant, which is evident in the galleries left behind. Larvae of C. femorata are legless, white grubs that have a large thoracic segment behind the head, which give it a “flat” appearance (Hansen 2011).

When pupating, these beetles burrow deep into the heartwood of the host plant to create pupal cells (Bright 1977). Pupation typically occurs from spring until late summer in Florida and can last up to 2 weeks (Spies 2018). Pupae are oblong and whitish yellow in color (Dreistadt 2016). The primary form of the life cycle that is recorded is emergence; the early stages of the life history of Chrysobothris species are difficult to determine and observe.

Adults

The adult flatheaded appletree borer is “bullet shaped” with a flat head, and large compound eyes (Figure 3). From the dorsal (top) view, the body of C. femorata is iridescent brown with prominent ridges and lighter colored metallic spots on each elytra (hard wing covers). On the ventral (bottom) side it may be iridescent brown, red, copper, or green. Males may be brighter green whereas females may appear more coppery.

Credit: Alexis Zapata and Lyle Buss

The abdomen is a chrome-like green color. The antennae are metallic brown and red with the last antennal segment being slightly tapered. The elytra are serrated (toothed) all along the margins. The femurs (long leg segment close to body) appear “swollen,” with the first set of legs having a large flat tooth (Bright 1977). The tibia (long leg segment away from body) has a single spine, and the tarsi (small segments at end of legs) may be iridescent green in color.

The head of C. femorata can be metallic brown, red, as well as iridescent green. The clypeus (facial plate above the mouth) is evenly rounded compared to other similar species, with a deep cinch in the center, resembling a number “3” (Figure 4).

Credit: Alexis Zapata and Lyle Buss

The adult C. chrysoela is also “bullet shaped” with a flat head and large compound eyes (Figure 5). The body of C. chrysoela is deep iridescent violet in color with distinctive iridescent yellow-green spots on each elytra (hard wing covers) that resemble coins. The elytra have fine teeth along the margins (outer edge of the wings) and the elytral apices (tips of the wing covers) are slightly tapered. The abdomen is a chrome blue-green color.

Credit: Alexis Zapata and Esnai Munthali

It is important to note that identification of these Chrysobothris species through morphological (physical) features alone may be difficult, especially in the case of C. femorata where there is a large species complex.

Sexing

Male flatheaded appletree borers have distinctive genitalia, with slightly asymmetrical lateral lobes (uneven outer prongs). The median lobe of the aedeagus (male genitalia) appears flat, is broader than that of similar species, and has a rounded apex (point) (Figure 6).

Credit: Alexis Zapata

Female flatheaded appletree borer genitalia have an upraised ridge in the center of the ovipositor (structure for laying eggs), with metallic brown-red divots on opposite sides of the ridge. There is a deep cinch or “v” at the tip of the ovipositor, with pointed apices (tips) (Figure 7).

Credit: Alexis Zapata

Male C. chrysoela have an aedeagus (male genitalia) that is acutely tapered (comes to a sharp point), appears flat, and is broad in width (Figure 8). The aedeagus has a thickened median lobe that is dark and tapers on the edge. The lateral lobes are typically symmetrical and flat in appearance. The pygidium (last segment on the abdomen) is rounded and iridescent blue for both sexes. The last tergites (dorsal plate) and some of the last sternites (ventral plate) may appear similar; it is hard to discern between the sexes unless the inner reproductive structures are examined.

Credit: Alexis Zapata

Damage

How do we assess damage?

Flatheaded borer damage may differ depending on the species, life stage, and condition of the host plant. A singular buprestid can cause substantial damage to host plants. Damage may be difficult to detect during early infestation stages and may vary depending on the host plant (Williamson 2023). Older bushes appear to be more susceptible than younger bushes. Also, plants bordering woodland appear to have higher infestation. In blueberries, damage may not be noticeably visible at the larval infestation stage but will become more apparent as the blueberry season progresses.

Commonly observed damage to the surface of the bark may include wood girdling or “tunnels” and frass (feces) from tunneling. Other types of noticeable damage are peeling outer bark, spots of exposed inner bark, and “D” shaped exit holes (Figure 9).

Credit: Alexis Zapata

Management

Monitoring

Monitoring for flatheaded borers in blueberries is primarily done through trapping and visual damage assessment. Currently, purple sticky panel traps that are placed in between afflicted bush clusters in the lower part of the canopy appear to work well for monitoring buprestids (Figure 10). It is recommended that traps are baited with lures specifically for attracting wood-boring beetles. Visual damage assessment can also be done; this involves inspecting suspected infested blueberry plants for previously mentioned signs of damage.

Credit: Alexis Zapata

Prevention

The primary method to prevent infestation by buprestids and other wood-boring beetles is to maintain overall crop health and remove dying, dead, or diseased plants from the field. Plants that are diseased, damaged, or stressed may be more susceptible to flatheaded borer infestation (Baker 2018). If a population becomes established, pruning of damaged branches and spraying insecticides is recommended.

Chemical Control

The primary form of prevention is to establish planting in areas where there is not a history of flatheaded borer infestation. Pesticide application can be used as a last resort. The type of insecticides used may vary depending on the production system (organic versus conventional). Afflicted bushes should be sprayed in the lower portion of the bush, with good coverage on the damaged bark and roots. Currently, there are no pesticides that are labelled for flatheaded borers in blueberries; however, research is ongoing, and pesticide recommendations will be forthcoming.

Conclusion

Management of these pests is important in maintaining crop integrity for blueberry farmers in Florida. Current methods of control are advancing as more research is conducted and new information is gathered about these species of interest. Further research is required to maximize efficiency in controlling Chrysobothris species and to better understand the full impact of these pests.

Acknowledgements

All field work and research regarding flatheaded borers was accomplished through the Small Fruit and Vegetable IPM lab. Special thanks to Esnai Munthali, Arden R. Lambert, Joey Gonsiorek, Elena M. Rhodes, James T. Brown, Jessica Diaz, and Fernando Miguelena for all your hard work with this research. Thank you to Dr. Karla Addesso, Axel Gonzalez Murillo, and the staff at the Otis L. Floyd Nursery Research Center for all your guidance. Identification of all samples was achieved with the help of Kyle E. Schnepp with the FDACS Division of Plant Industry and Joshua Basham with USDA. Special thanks to Lyle Buss who aided with photography of some specimens.

References

Addesso, K., A. Gonzalez, J. Oliver, and A. Witcher. 2021. Flatheaded Borer Management in Nurseries with Winter Cover Crops. Tennessee State University Extension. Retrieved May 7, 2023. https://www.tnstate.edu/extension/documents/Flatheaded%20Borer%20Management%20with%20Cover%20Crops%201.pdf

Baker, J. 2018. Flatheaded Appletree Borer. NC State Extension Publications. N.C. Cooperative Extension. PDIC Factsheets. Retrieved May 7, 2023. https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/flatheaded-appletree-borer#section_heading_12979

Bright, D. E. 1977. Metallic Wood-boring Beetles of Canada and Alaska: Coleoptera, Buprestidae. Research Branch, Agriculture Canada. Volume 15.

Dreistadt, S. H. 2016. Pests of Landscape Trees and Shrubs: An Integrated Pest Management Guide. UC ANR Publication 3359. Third Edition.

Hansen, J. A., F. A. Hale, and W. E. Klingeman. 2011. Identifying the Flatheaded Appletree Borer (Chrysobothris femorata) and Other Buprestid Beetle Species in Tennessee. SP503-I. University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture Extension. Retrieved May 10, 2023. https://www.tnstate.edu/faculty/ablalock/documents/Flatheaded%20Apple%20Tree%20Borer.pdf

Rudolph, E., and N. Wiman. 2023. “Insights from Specimen Data for Two Economic Chrysobothris Species (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) in the Western United States.” Annals of the Entomological Society of America 116 (4): 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/saad009

Spies, J. 2018. “Beetle Borers in Blueberry.” UF/IFAS Entomology and Nematology Department Blogs. Retrieved May 1, 2023. https://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/entnemdept/2018/07/06/beetle-borers-in-blueberry/

USDA. 2022. State Agriculture Overview. National Agricultural Statistics Service. https://www.nass.usda.gov/Quick_Stats/Ag_Overview/stateOverview.php?state=FLORIDA

Williamson, Z. V., W. G. Hudson, and S. V. Joseph. 2023. Flatheaded Appletree Borer: A Pest of Trees in Nurseries and Landscapes. UGA Cooperative Extension Circular 1261. Retrieved May 10, 2023. http://extension.uga.edu/publications/detail.html?number=C1261