This publication is intended for the public, UF/IFAS Extension agents, and growers to provide an overview of predatory mite Amblyseius tamatavensis. This information includes the description, lifecycle, and potential for this predatory mite to be used as a biological control agent for hemipteran pests.

Introduction

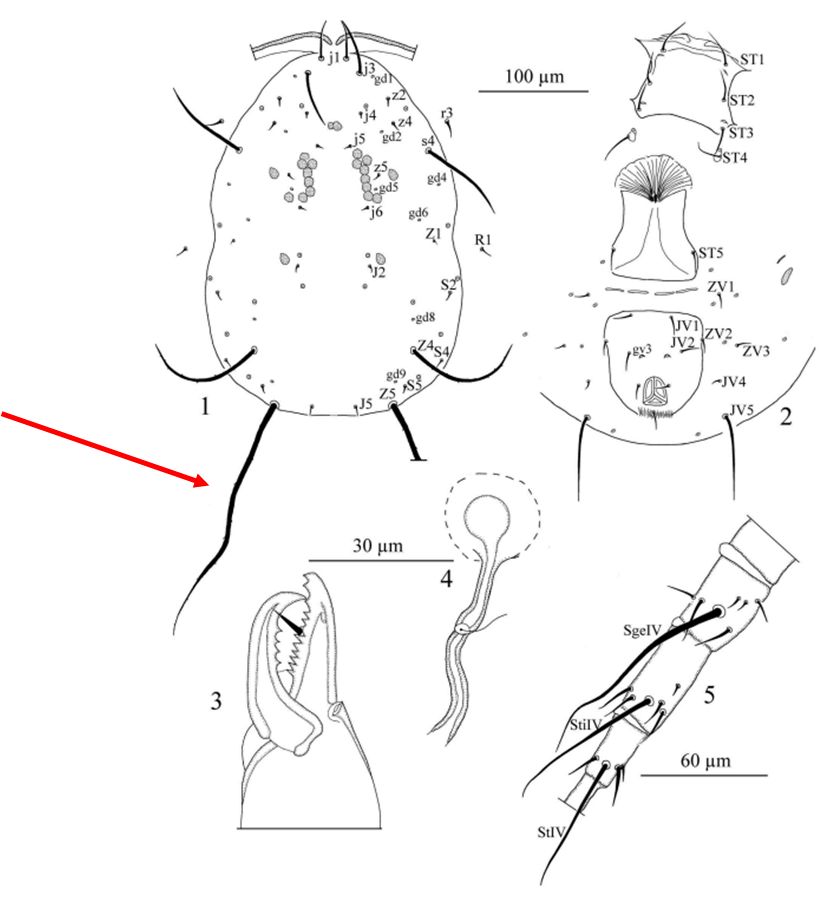

The predatory mite Amblyseius tamatavensis (Blommers) belongs to the order Mesostigmata and the family Phytoseiidae (Figure 1). This family is important because it includes commercially available biological control agents and natural enemies of plant-feeding mites and small, soft-bodied insects (Döker et al. 2018). Amblyseius tamatavensis is a generalist predatory mite, and it has been found in many cropping systems feeding on small hemipteran insects and pollen when prey is not present (McMurtry et al. 2013).

Credit: Yisell Velazquez-Hernandez and Maria A. Canon, UF/IFAS Tropical Research and Education Center

Identification

Amblyseius tamatavensis was first described from kaffir lime (Citrus hystrix DC; Sapindales: Rutaceae) on the island of Madagascar. The main character used for identification is the spermatheca, a sack where females store and collect the sperm after mating (Figure 2.4) (Döker et al. 2018). Like many mites, adult A. tamatavensis females have short, stiff hair on their exoskeletons. These hairs are called setae. Amblyseius tamatavensis has a pair of very long setae on the lower part (posterior) of its body. These are called Z5 (Figure 2.1). Its spermatheca is elongated with a tube-shaped structure called calyx, that directs the sperm to the sack (Figure 2.4). The area where the mite’s anus is located, also known as ventrianal shield, is not vase-shaped, but it rather has a trapezoid shape (Figure 2.2).

Credit: Döker et al. 2018, used with permission

Adult A. tamatavensis females lay their eggs on the undersides of leaves. When A. tamatavensis mites have been feeding on whiteflies, their eggs can sometimes be found in the exuvia (molted exoskeletons) of emerged adults. The white and oval eggs take approximately 2–3 days to hatch at 26.7°C (80.06°F).

Credit: Yisell Velazquez-Hernandez, UF/IFAS Tropical Research and Education Center

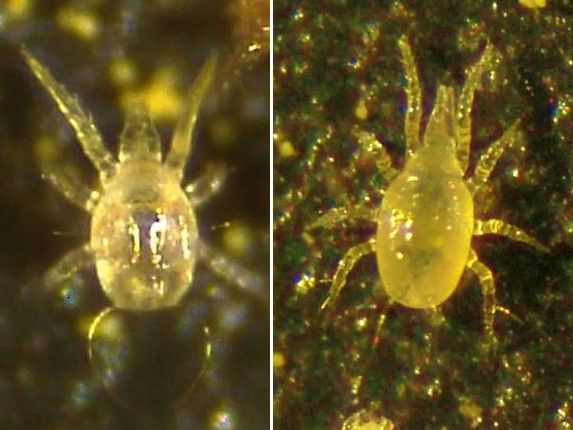

Amblyseius tamatavensis larvae are six-legged and transparent to white in color. This is a non-feeding stage. Within one to two days, larvae molt to the protonymph stage and begin to feed. Protonymphs and deutonymphs have four pairs of legs and continue to increase in size.

Credit: Yisell Velazquez-Hernandez and Maria A. Canon, UF/IFAS Tropical Research and Education Center

Adult females are approximately 0.1 mm (0.004 in) long and are slightly larger than males. Males and females may be light reddish to dark red; however, color varies based on food source, including prey.

Credit: Yisell Velazquez-Hernandez and Maria A. Canon, UF/IFAS Tropical Research and Education Center

Distribution

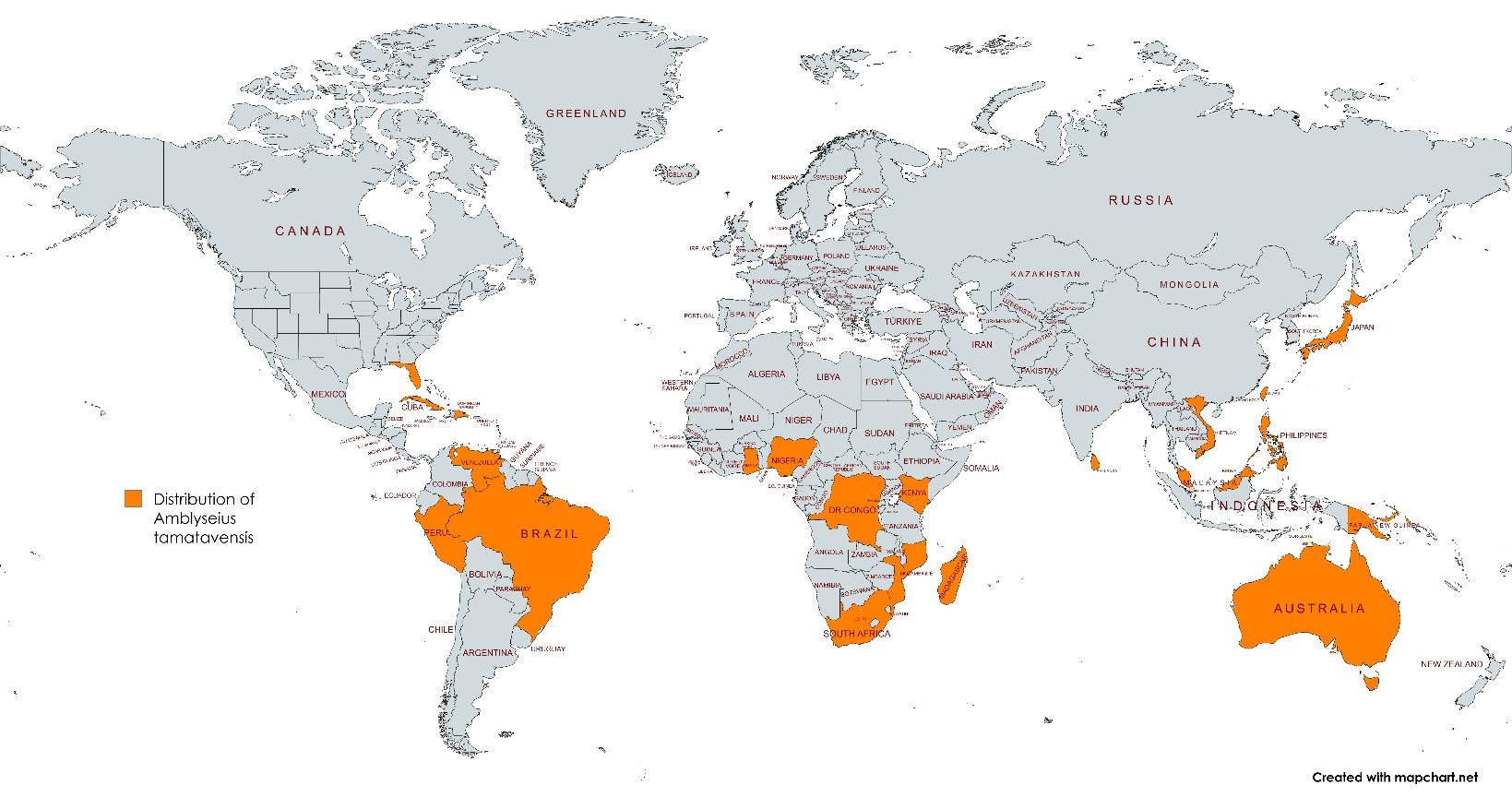

Amblyseius tamatavensis has been reported from approximately twenty tropical and subtropical regions worldwide in various natural and agricultural habitats. Populations of this mite have been reported in many countries including Australia, Benin, Brazil, Burundi, Cameron, Cook islands, Cuba, Dominican Republic, DR Congo, Easter Island, Fiji, Ghana, Guadeloupe, Indonesia, Japan, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Malaysia, Marie-Galante, Martinique, Mauritius, Mayotte island, Mozambique, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Philippines, Reunion Island, Rwanda, Singapore, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Thailand, Uganda, the United States, Vanuatu, Venezuela, Vietnam, and Western Samoa (Demite et al. 2024). In the United States it was reported for the first time in Homestead (Miami-Dade County), Florida in 2018 (Döker et al. 2018). In 2024, it was subsequently reported in Lake and Saint Lucie Counties (Demard et al. 2024).

Credit: Maria A. Canon, UF/IFAS Tropical Research and Education Center (https://www.mapchart.net/)

Economic Importance

Interest in phytoseiid mites for biological control has increased with the shift toward more sustainable pest management practices. Some phytoseiid species can be specialist or generalist feeders (McMurtry et al. 2013). Worldwide there are approximately 2,700 species and 91 genera of phytoseiid mites described (Chant and McMurtry 2007). Research has found that predatory mite A. tamatavensis could be an effective biological control agent for sweet potato whitefly (Bemisia tabaci [Gennadius]) biotype B in Brazil (Cavalcante et al. 2016). In Peru, A. tamatavensis was found feeding on eriophyid mites (Phyllocoptruta oleivora [Ashmead]) and western flower thrips (Frankliniella occidentalis [Pergande)) in citrus (Jorge et al. 2021). Ho and Chen (2001) also reported that A. tamatavensis could be an effective predator for melon thrips (Thrips palmi Karny) pests in Taiwan.

Amblyseius tamatavensis has been found feeding on different whitefly species, making it a potential predatory mite for a biological program. It has been found consuming eggs of sweetpotato whitefly on economically valuable host crops such as cotton, solanaceous crops, and melons (Barbosa et al. 2019). Amblyseius tamatavensis was also found feeding on plants infested with banded-wing whitefly Trialeurodes abutiloneus (Haldeman) in south Florida (Döker et al. 2018). South Florida populations of A. tamatavensis are being used to perform predation experiments on the fig whitefly Singhiella simplex (Singh) on weeping ficus (Ficus benjamina) (Figure 3).

With insecticide resistance on the rise for whitefly pests, alternative management practices, such as biological control, should be considered. Research has shown that A. tamatavensis can be mass reared on factitious prey (Thyreophagus cracentiseta; Acari: Acaridae) (Massaro et al. 2021). Once it has become commercially available, A. tamatavensis can be released and used in augmentative biological control programs to manage hemipteran pests in different cropping systems. Since A. tamatavensis naturally occurs in Florida, growers and landscaping companies can conserve its populations by following sustainable practices against arthropod pests that include pruning, and selection of biorational pesticides rather than conventional pesticides. As a generalist predator, A. tamatavensis can feed and survive on pollen. Therefore, stakeholders interested in enhancing an A. tamatavensis population on their crops may wish to consider using cattail (Typha sp. L.) pollen that is available in the market.

References

Barbosa, M. F. C., M. Poletti, and E. C. Poletti. 2019. “Functional response of Amblyseius tamatavensis Blommers (Mesostigmata: Phytoseiidae) to eggs of Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) on five host plants.” Biological Control Volume 138, 104030, ISSN 1049-9644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2019.104030

Cavalcante, A. C. C., M. E. A. Mandro, E. R. Paes, and G. J. Moraes. 2016. “Amblyseius tamatavensis Blommers (Acari: Phytoseiidae) a candidate for biological control of Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) biotype B (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) in Brazil.” International Journal of Acarology 43:10–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/01647954.2016.1225816

Cavalcante, A. C., V. L. V. Santos, L. C. Rossi, and G. J. Moraes. 2015. “Potential of five Brazilian populations of Phytoseiidae (Acari) for the biological control of Bemisia tabaci (Insecta: Hemiptera).” Journal of Economic Entomology 108:29–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/tou003

Chant, D. A., and J. A. McMurtry. 2007. Illustrated keys and diagnoses for the genra and subgenra of the Phytoseiidae of the word (Acai: mesostigmata). Indira Publishing House, Michigan, USA. 220 p.

Demite, P. R., G. J. de Moraes, J. A. McMurtry, H. A. Denmark, and R. C. Castilho. 2024. Phytoseiidae Database. Available from htpps://www.lea.esalq.usp.br/phytoseiidae (accessed 10/8/2024)

Demard, E. P., I. Döker, and J. A. Qureshi. 2024. “Incidence of eriophyid mites (Acariformes: Eriophyidae) and predatory mites (Parasitiformes: Phytoseiidae) in Florida citrus orchards under three different pest management programs.” Experimental and Applied Acarology 92:323–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-023-00882-4

Döker, İ., Y. V. Hernandez, C. Mannion, and D. Carrillo. 2018. “First report of Amblyseius tamatavensis (Acari: Phytoseiidae) in the United States of America.” International Journal of Acarology 44:2–3, 101–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/01647954.2018.1461132

Ho, C. C., and W. H. Chen. 2001. “Life history and feeding amount of Amblyseius asetus and A. maai (Acari: Phytoseiidae) on Thrips palmi (Thysanoptera: Thripidae)” Formosan Entomologist 21:321–328.

Jorge, S. J., P. R. Demite, and G. J. de Moraes. 2021. “First report of Amblyseius tamatavensis Blommers, 1974 (Acari: Phytoseiidae) in Peru, with predation observation and a key for the Amblyseius species reported so far from that country.” Entomological Communications 3:ec03037. https://doi.org/10.37486/2675-1305.ec03037

Massaro, M., M. Montrazi, J. W. S. Melo, and G. J. de Moraes. 2021. “Small-Scale Production of Amblyseius tamatavensis with Thyreophagus cracentiseta (Acari: Phytoseiidae, Acaridae).” Insects 12:848. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects12100848

McMurtry, J. A., G. J. de Moraes, and N. F. Sourassou. 2013. “Revision of the lifestyles of phytoseiid mites (Acari: Phytoseiidae) and implications for biological control strategies.” Systematic and Applied Acarology 18:297–320. https://doi.org/10.11158/saa.18.4.1

McMurtry, J. A., and G. T. Scriven. 1965. “Insectary production of phytoseiid mites.” Journal of Economic Entomology 58:282–284. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/58.2.282