The purpose of this publication is to provide Florida blueberry growers, Extension agents, blueberry breeders, and other members of the blueberry industry with information on the benefits of cross-pollination in southern highbush blueberry production systems and advice on how to plant a highly productive orchard optimized for cross-pollination and fruit production.

Introduction

Pollination is a key stage in the life cycle of plants that produce seeds and fruits, but it can easily fail (Wilcock and Neiland 2002). Pollination involves the transport of pollen from the stamens, the male part of the flower, to the pistil, the female part. Because plants are immobile, an agent must be involved to disperse the pollen: this agent can be abiotic, such as wind or water, or biotic, such as insects or birds. The majority of flowering plants (angiosperms) are pollinated by animals, and insect pollinators represent over 99% of described pollinator species (Ollerton 2021). In plants pollinated by insects, fruit and seed production can be limited by pollination if there are not enough plants producing compatible pollen, or if there are not enough insects to transport the pollen.

Southern highbush blueberry, hereafter called SHB, are Vaccinium corymbosum interspecific hybrids. SHB cultivars are the result of crosses between Vaccinium corymbosum, V. darrowii, and V. virgatum (Brevis et al. 2008), and are the most widely planted blueberry crops in Florida. Blueberry pollination relies heavily on insect pollinators, and fruit set and yields are very low in the absence of insects (Benjamin and Winfree 2014; DeVetter et al. 2022). Additionally, SHB fruit set generally increases with cross-pollination between two different plants as compared to self-pollination (Chavez and Lyrene 2009). The effect of insect pollinators on yield has been intensively studied, but less is known about the effect of pollen quality on fruit production, including how pollination between different cultivars affects not just fruit set but fruit size and quality. Additionally, optimal planting arrangements to encourage cross-pollination between cultivars is not well-documented. In this article, we present information on the benefits of cross-pollination for SHB production and how best to combine different SHB cultivars to ensure high-quality pollination and fruit production.

Self-Pollination Versus Cross-Pollination

Blueberries are partially self-fertile, meaning that they can produce some fruits and seeds with self-pollination, but cross-pollination has been shown to increase the quantity and quality of fruit produced (Figure 1) (Lang and Danka 1991; Taber and Olmstead 2016; DeVetter et al. 2022). Cross-pollination occurs when a plant’s flower is pollinated by pollen from a different plant. But when the flower is pollinated by pollen from the same plant, self-pollination occurs. Self-pollination can happen either within an individual flower, or between two flowers on the same plant. In general, for woody cultivated plants, a cultivar is a clonal variety; as a result all plants of the same cultivar are genetically identical. Thus, pollination that occurs between two plants of the same cultivar is functionally self-pollination.

Credit: Rachel Mallinger, UF IFAS

Blueberries display early-acting inbreeding depression, the mechanism thought to contribute to the reduced quantity and quality of fruits with self-pollination, though the extent to which this occurs varies across blueberry cultivars and species (Hokanson and Hancock 2000). Self-fertile cultivars can often achieve high yields with self-pollination but self-infertile cultivars will have poor seed or fruit production with self-pollination, and in some cases, production will be zero.

Mixing Cultivars for Cross-Pollination

In general, for crops that are partially or fully self-infertile, cross-pollination is required to maximize yields, but not all cross-pollen is of equal quality. Thus, certain combinations of cultivars can produce more or larger fruits and seeds. The pollen donor can also affect fruit quality, influencing attributes like color, chemical composition, firmness, or ripening time (Denney 1992; McKay and Crane 1939). Thus, by choosing cultivars carefully, it is possible to improve the quality and quantity of the fruit or seed produced.

The timing of flowering can affect how productive and successful certain cultivars are in a mixed planting layout. Cultivars must overlap in bloom for cross-pollination to occur. To ensure that bloom overlaps even under unpredictable weather and erratic crop phenology, it is best to plant multiple cultivars in one field. Furthermore, each cultivar responds differently to temperature and water stress, and combining several cultivars may mitigate the negative effects of temperature and water stress on pollen production and fertility, thus ensuring pollination, fertilization, and yields.

Studying the Benefits of Cross-Pollination for Modern SHB Cultivars

To understand the degree to which cross-pollination enhances SHB blueberry quantity or quality, a controlled pollination experiment was conducted across several SHB cultivars to compare the size and quality of fruit produced from self-pollination and cross-pollination. Individual flowers were hand-pollinated with either self-pollen or cross-pollen. In the cross-pollination treatment, pollen from five different cultivars was tested separately for each recipient cultivar. Fruits from all pollination treatments were harvested, and fruit mass, time to ripen, firmness, and sugar and acid content were measured. Each fruit was individually weighed to obtain its mass in grams. The number of days between flower opening and fruit harvest corresponds to the ripening time. The firmness of individual harvested berries was measured (in g/mm) using a firmness tester. After measuring firmness, fruits were crushed and the sugar concentration (Brix, varying from 0%–90%) and acidity (varying from 0.1%–4.0%) of fruit juice from each fruit was measured using a Brix/acidity meter for blueberries. Cultivars tested included ‘Arcadia’, ‘Avanti’, ‘Chickadee’, ‘Colossus’, ‘Emerald’, ‘Farthing’, ‘Kestrel’, ‘Meadowlark’, ‘Optimus’, and ‘Sentinel’.

Almost all pollination treatments set fruit. However, when cultivars were pollinated with cross-pollen rather than self-pollen, fruit mass increased significantly for nine of the ten cultivars, all except ‘Kestrel’, and by an average of 42% (Table 1, range 6%–58%). Ripening time decreased significantly for eight of the ten cultivars with cross-pollination, all except ‘Emerald’ and ‘Farthing’, and by an average of eight days (Table 1, range 3–27 days). On the other hand, fruit firmness did not change with cross-pollination for six of the ten cultivars studied. Firmness increased with cross-pollination for 'Chickadee', 'Colossus', and 'Meadowlark', and decreased with cross-pollination for ‘Farthing’ (Table 1). Sugar content was affected by cross-pollination for only five of the ten cultivars studied (Table 1): it increased significantly for ‘Avanti’ and decreased significantly for ‘Arcadia’, 'Colossus', 'Farthing’, and ‘Kestrel’. Acidity was affected by cross-pollination in only three of the ten cultivars studied (Table 1): it increased significantly in ‘Colossus’ and ‘Kestrel’ and decreased significantly in ‘Farthing’. Finally, the ratio between sugar and acid was affected by cross-pollination for five of the ten cultivars studied (Table 1): it increased significantly for ‘Avanti’ and decreased significantly for 'Arcadia', 'Colossus', 'Kestrel', and 'Meadowlark'. Therefore, cross-pollination increased fruit mass and accelerated berry ripening consistently. However, cross-pollination had variable results on fruit quality parameters like firmness, sugar concentration, and acidity.

How to Select Cultivars for Cross-Pollination

By Genotype

Cross-pollination between SHB cultivars can thus increase yields, but which cultivars should be combined? Our results show that cross-pollination as compared to self-pollination will generally result in higher yields, and shorter ripening times regardless of cultivar combinations. Given that cross-pollen from any cultivar is generally better than self-pollen, other considerations such as bloom time or management compatibility may be more important when selecting cultivars to interplant.

By Flowering Time

The timing, or phenology, of flowering is very important to consider because the cross-pollinating cultivars must have overlapping bloom periods. It may also be advantageous to choose more than two cultivars with staggered and partially overlapping bloom periods so that at least two cultivars are blooming at the same time to provide pollination insurance against variable weather.

Across eight farms throughout different growing regions in Florida, phenology data was collected for numerous cultivars in 2023 (Table 2). These data can provide insights into what cultivars should be planted together for cross pollination based on overlapping bloom. For example, the cultivars ‘Albus’, ‘Optimus’, and ‘Arcadia’ have overlapping peak bloom periods across most farms and are thus good candidates for mixed planting. However, bloom times for cultivars varied between growing regions, with cultivars overlapping at some farms but not others (Table 2). Thus, it is difficult to predict flowering time and bloom overlap only from latitude. Additionally, the bloom period for many cultivars is long. Considering the overlap in peak bloom (at least 50% of flowers are open) will likely have a greater effect on cross-pollination than overlap in early bloom or end of bloom.

By Management

For optimal production, it is also important to make sure that the crop management of the selected cultivars is compatible, because mixing cultivars within a block may not be feasible if the cultivars’ management requirements are too disparate. The cultivars in a block must have similar needs so that they can be managed in a similar way: they should have the same water and fertilizer requirements, be sprayed with the same pesticides at the same general times, and have similar fruit ripening times. If machine harvesting is involved, it would be most feasible to plant cultivars that can all be machine-harvested in the same block. Additionally, cultivars that are all deciduous or all evergreen may be easier to manage within the same block.

How to Arrange Cultivars in a Block

Distance Between Cultivars

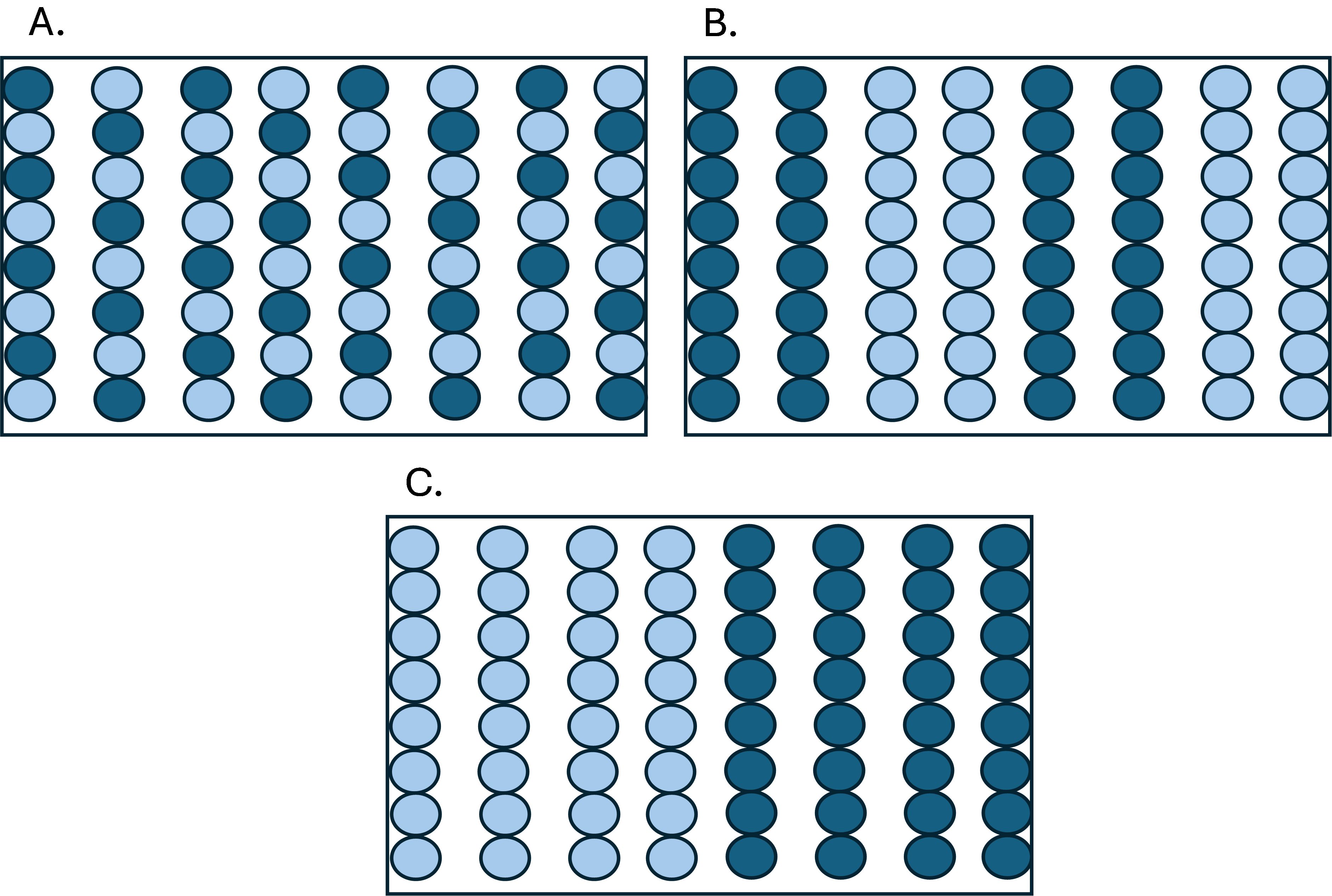

The distance that pollen will travel in a field via wind or insects is a very important factor in determining how different cultivars should be planted relative to one another. In general, across different crops, the greater the distance from the pollen donor, the lower the probability of pollination by that donor (Clobert et al. 2012; Lagache et al. 2013). Most pollination events occur at short distances. For insect-pollinated crops, pollination is determined by the foraging behaviors of the insect pollinators. There is limited information on pollen dispersal distance in blueberry fields. However, in other crops, cross-pollination is reduced with increasing distance between cultivars. In tree orchards, a distance of just ~5 m (~16.4 ft) between cultivars reduces pollination, which limits fruit and nut production (Chabert et al. 2024). Cross-pollination events can occur over longer distances but are infrequent. Consequently, blueberry cultivars should be planted as close to one another as possible, in alternating rows or sets of two rows, for optimal cross-pollination (Mallinger et al. 2024; Figure 2).

Credit: Rachel Mallinger, UF/IFAS

Orientation and Arrangement of Cultivars

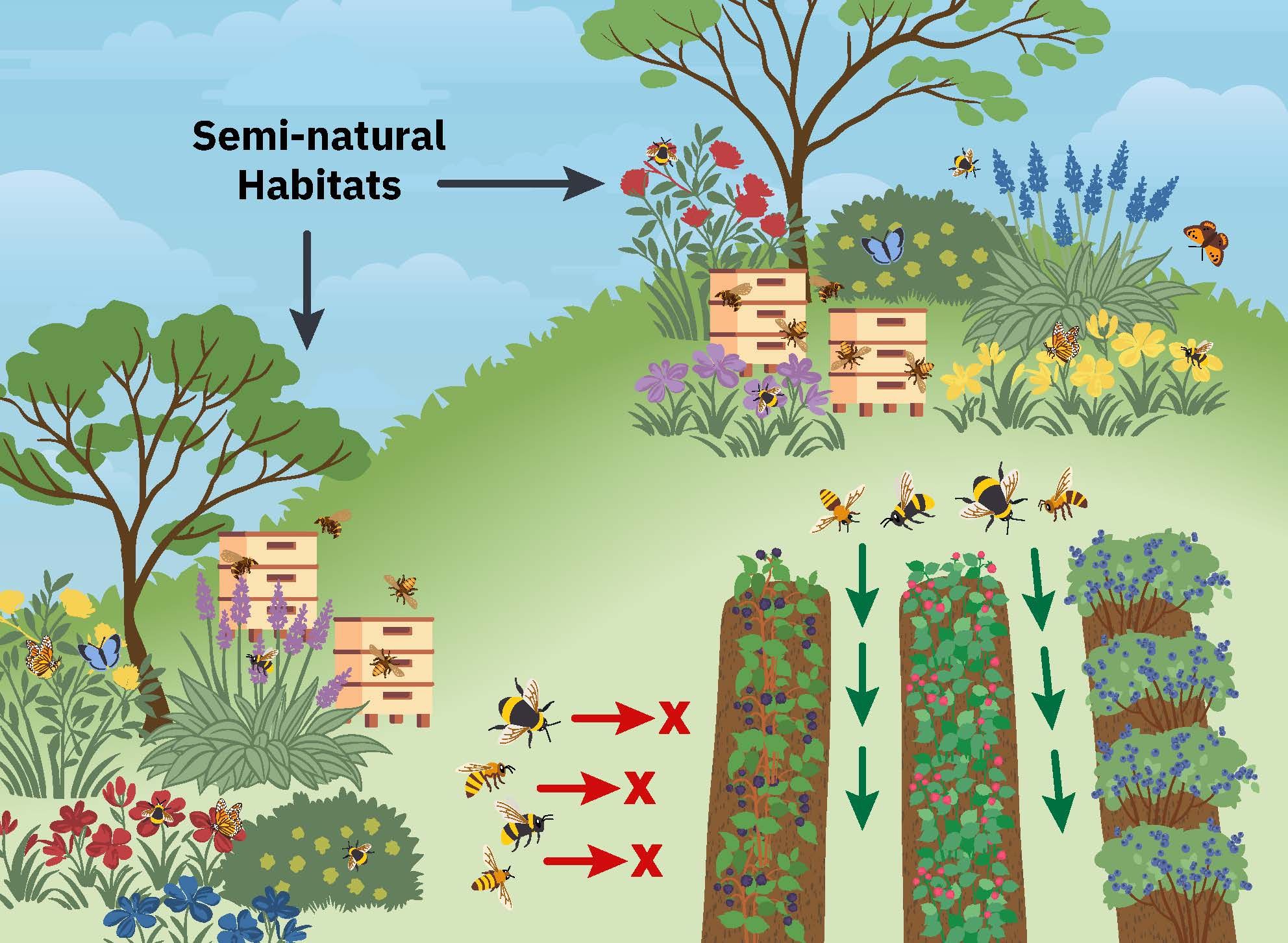

Managed honey bees (Apis mellifera) and other pollinators are known to forage along linear structures, a behavior known as traplining. As honey bees preferentially move along orchard rows, there may be more pollen exchange between different cultivars if they are planted together within the same row (Mallinger et al. 2024; Figure 3). Moreover, if the rows are perpendicular to the surrounding natural habitat, insect movement into the crop from the natural environment may be more frequent (Anders et al. 2023). Alternatively, if the rows are parallel to the edge of an adjacent natural habitat, they can act as a barrier for pollinating insects, and insect movement from the edge to the center of the field will be impeded (Figure 3). In addition, providing pollinators with floral resources, nesting resources, and protection from pesticides can increase their diversity and overall numbers. When insect pollinator communities are diversified, insect interactions and movements are more frequent, increasing cross-pollination frequencies within and across rows (Brittain et al. 2013).

Credit: Leah Welch, UF/IFAS Communications

Conclusion

Even though blueberries are partially self-fertile, it is better to plant several cultivars together, given that the fruit formed by cross-pollination is heavier and ripens faster, thus improving yields and marketability. It is important to mix cultivars that flower at the same time and that can be managed in the same way. Additionally, having a high diversity of cultivars in one area provides insurance that overlapping bloom and successful cross-pollination will occur under varying weather conditions. Cultivars planted within the same row may result in optimal cross-pollination, but planting cultivars next to one another in adjacent rows can result in cross-pollination as well. Whether planted within the same or different row, for optimal cross-pollination, cultivars should be as close to one another as possible given management and plant spacing restrictions.

References

Anders, M., I. Grass, V. M. G. Linden, P. J. Taylor, and C. Westphal, 2023. "Smart orchard design improves crop pollination." Journal of Applied Ecology 60:624–637. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.14363

Benjamin, F. E., and R. Winfree. 2014. "Lack of Pollinators Limits Fruit Production in Commercial Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum)." Environmental Entomology 43:1574–1583. https://doi.org/10.1603/EN13314

Brevis, P. A., N. V. Bassil, J. R. Ballington, and J. F. Hancock. 2008. "Impact of Wide Hybridization on Highbush Blueberry Breeding." Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 133 (3): 427–437. https://doi.org/10.21273/JASHS.133.3.427

Brittain, C., N. Williams, C. Kremen, and A.-M. Klein. 2013. "Synergistic effects of non-Apis bees and honey bees for pollination services." Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 280:20122767. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.2767

Chabert, S., M. Eeraerts, L. W. DeVetter, M. Borghi, and R. E. Mallinger. 2024. "Intraspecific crop diversity for enhanced crop pollination success. A review." Agronomy for Sustainable Development 44:50 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-024-00984-2

Charlesworth, D., and B. Charlesworth. 1987. "Inbreeding Depression and Its Evolutionary Consequences." Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 18:237–268. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.18.110187.001321

Chavez, D. J., and P. M. Lyrene. 2009. "Effects of Self-Pollination and Cross-Pollination of Vaccinium darrowii (Ericaceae) and Other Low-Chill Blueberries." HortScience 44 (6): 1538–1541. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.44.6.1538

Clobert, J., M. Baguette, T. G. Benton, and J. M. Bullock. 2012. Dispersal Ecology and Evolution. OUP Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199608898.001.0001

Denney, J. O. 1992. "Xenia Includes Metaxenia." HortScience 27:722–728. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.27.7.722

DeVetter, L. W., S. Chabert, M. O. Milbrath, et al. 2022. "Toward evidence-based decision support systems to optimize pollination and yields in highbush blueberry."Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.1006201

Hokanson, K., and J. Hancock. 2000. "Early-acting inbreeding depression in three species of Vaccinium (Ericaceae)." Sexual Plant Reproduction 13:145–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004970000046

Lagache, L., E. K. Klein, E. Guichoux, and R. J. Petit. 2013. "Fine-scale environmental control of hybridization in oaks." Molecular Ecology 22 (2): 423–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12121

Lang, G. A., and R. G. Danka. 1991. "Honey-bee-mediated Cross- versus Self-pollination of `Sharpblue’ Blueberry Increases Fruit Size and Hastens Ripening." Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 116:770–773. https://doi.org/10.21273/JASHS.116.5.770

Larue, C., E. Klein, and R. Petit. 2022. "Sexual interference revealed by joint study of male and female pollination success in chestnut." Molecular Ecology 32:1211–1228. https://doi.org/10.22541/au.165759852.21474646/v1

Mallinger, R. E., S. Chabert, S. M. Naranjo, and V. Vo. 2024. "Diversity and spatial arrangement of cultivars influences bee pollination and yields in southern highbush blueberry Vaccinium corymbosum x darrowii." Scientia Horticulturae 335:113321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2024.113321

McKay, J. W., and H. L. Crane. 1939. "Xenia in the Chestnut." Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.89.2311.348

Ollerton, J. 2021. Pollinators and Pollination: Nature and Society. Pelagic Publishing, London, UK. https://doi.org/10.53061/JAOK9895

Taber, S .K., and J. W. Olmstead. 2016. "Impact of Cross- and Self-Pollination on Fruit Set, Fruit Size, Seed Number, and Harvest Timing Among 13 Southern Highbush Blueberry Cultivars." HortTechnology 26:213–219. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTTECH.26.2.213

Wilcock, C. C., and M. R. M. Neiland. 2002. "Pollination failure in plants: why it happens and when it matters." Trends in Plant Science 7:270–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02258-6

Table 1. Summary of the effect of cross-pollination (all cross-pollen donors combined) in comparison to self-pollination for six variables of fruit size and quality measured across all cultivars. These results are based on controlled pollination in greenhouses.

1For fruit mass, firmness, sugar content, acidity, and sugar:acidity ratio (S:A ratio), the results are in percentage of change from cross-pollination in comparison to self-pollination (+ indicates cross-pollination increased the variable in comparison to self-pollination).

2For time to ripen, the results are in days comparing cross-pollination to self-pollination (− indicates cross-pollination reduced ripening time in comparison to self-pollination).

3Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences at * P < 0.10, ** P < 0.05, *** P < 0.01, and **** P < 0.001. Insignificant differences at P > 0.10 are noted as “NS”.

Table 2. Bloom periods for cultivars planted across eight farms in four Florida regions. Early bloom (10%–50% flowers open, “E”) is shown in light gray and peak–late bloom (~50%+ flowers open, “L”) in dark gray. The bloom period spans from December–March with Julian week (“Wk”) noted.