Introduction

The peanut burrower bug, Pangaeus bilineatus (Say), is a small blackish soil-dwelling insect in the family Cydnidae (Order: Hemiptera) native to Central and North America (Figure 1). Like most hemipterans, they have piercing-sucking mouthparts to feed on plant tissue. Members of the family Cydnidae are known as burrower or burrowing bugs as most species have fossorial legs used to dig in the soil and feed on plant root tissue. In the U.S., 27 species of burrower bugs are considered pests in a variety of crops, including cotton, spinach, peppers, and strawberries. Of the burrower bugs found in peanut fields, Pangaeus bilineatus is the only economically important pest (Aigner et al., 2021). The peanut burrower bug can be a significant pest in peanut-growing regions of the U.S., predominantly in the Southeast and Texas, where it can cause yield loss and grade reductions. Due to its soil-dwelling lifestyle, it can be challenging to detect in the field. This document serves as a guide for Extension agents, growers, and the general public on the biology, life cycle, and identification of the peanut burrower bug.

Credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS

Distribution

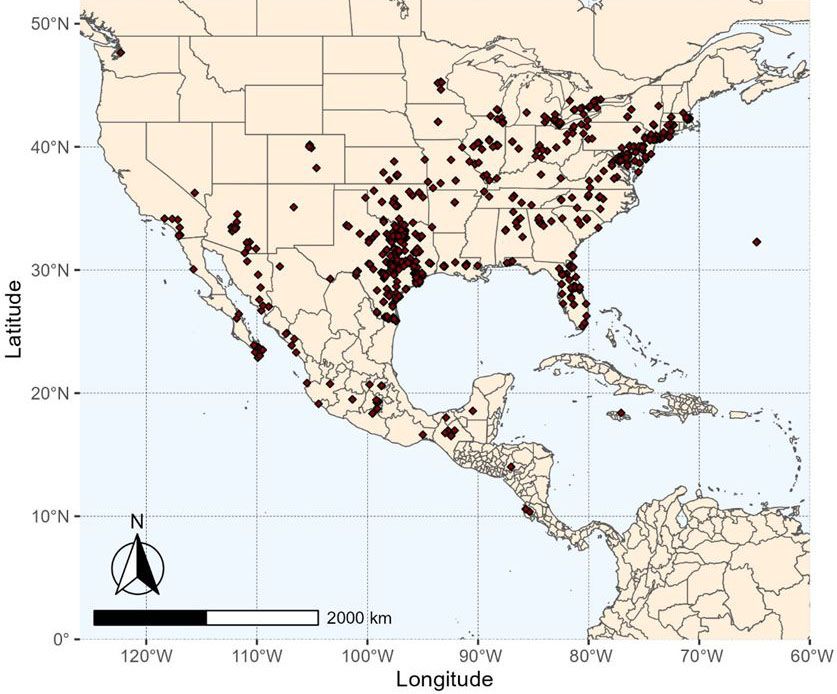

Pangaeus bilineatus is native to the U.S. and Central America. According to species records, it is widely distributed in the U.S., from the Atlantic coast from New York to Florida, to the midwestern states of Ohio, southern Wisconsin, and Kansas, southwest across New Mexico and Arizona, and into the Imperial Valley of California (GBIF 2023). Outside of the U.S. it has also been recorded through Baja, California, and south through Mexico to Guatemala, and a single specimen report in Bermuda (Sailer 1954) (Figure 2). Literature also reports P. bilineatus in the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec, Puerto Rico and Nebraska (Sailer 1954). In the primary peanut-growing region of the southeastern U.S., Pangaeus bilineatus has been reported in 27 counties across Alabama, Florida, and Georgia (Chapin et al. 2001, Chapin and Thomas 2003). Historically, the peanut burrower bug first became an agricultural concern in Virginia in 1934 when it was observed in spinach (Gould 1931). In the 1960s, burrower bugs caused heavy agricultural damage to peanut crops in Texas and Alabama (Chapin and Thomas 2003).

Credit: Isaac L. Esquivel, UF/IFAS

Credit: Mark Abney and Ben Aigner, University of Georgia

Description and Life Cycle

Like most hemipterans, Pangaeus bilineatus are paurometabolous, meaning they undergo incomplete metamorphosis from egg to five nymphal instars to adult. They are thought to have at least three generations per year in field settings but can complete a full generation within one month under laboratory conditions (Aigner et al., 2021). A study in Texas indicates that they overwinter as adults in soil depths of 6–8 inches starting in December and become active again in late February to early March, moving toward the soil surface as temperatures increase (Cole 1988). However, in Georgia, active Pangaeus bilineatus nymphs were observed during December–February, suggesting a portion of the population may not enter diapause in the Florida panhandle (Ainger et al., 2023). After mating, females lay eggs in the soil near roots and seed pods during early spring (Smith and Holmes 2002). Adults and nymphs can be observed overwintering near field edges, beneath the soil surface, and near other hosts or grasses (Smith and Pitts 1974). The population density of these insects tends to peak as kernels fully develop and fill the pod, with populations often remaining high until harvest (Chapin and Thomas 2003).

Adults

Pangaeus bilineatus adults are among the larger species of common burrower bugs found in peanut. They are oval-shaped and light brown to black in color, and their body length ranges from 5.85 mm to 7.6 mm (0.23 in to 0.30 in). Along with body size, the primary defining taxonomic feature of Pangaeus bilineatus is the presence of a deep, sharply impressed line along the anterior margin of the pronotum. Other defining taxonomic features include no tubercles on the ventral surface of the posterior femora, no punctures in the subapical impression of the pronotum, and the presence of three or more submarginal punctures on each jugum (Sailer 1954b). Other characteristics include four antennal segments, an abundance of spines on their tibiae angled at 45 degrees, and their scutellum not extending to the tip of the abdomen.

Nymphs

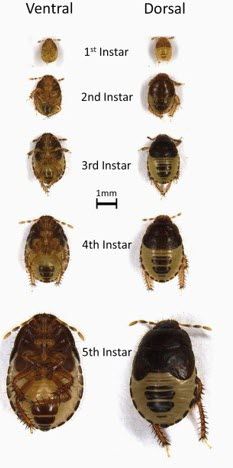

Pangaeus bilineatus undergoes five nymphal stages (instars) and spends most of their time under the soil surface (Figure 3). Nymphs tend to be lighter brown in color and look very similar to adults in body structure (Aigner et al., 2021). The average pronotum width increases with each instar: first instar (0.66 mm (0.026 in)) and beige in color, second instar (0.9 mm (0.035 in)) and light brown in color, third instar (1.27 mm (0.05 in)) dark brown in color, fourth instar (1.8 mm (0.071 in)) similar in color to third instar, and fifth instar (2.6 mm (0.10 in)) darker with distinct wing pads (Aigner et al., 2021). Developing nymphs will subsist on the roots of plants or the maturing kernels of seedlings (Smith and Holmes 2002). Even the smallest nymphs have mouthparts capable of piercing through the hull of peanuts, though they can feed more readily when pods become full (Smith and Pitts 1974). The mouthparts of nymphs will grow by an average of 1.44 mm per molt, allowing them to reach kernels more easily as they grow (Aigner et al. 2021).

Eggs

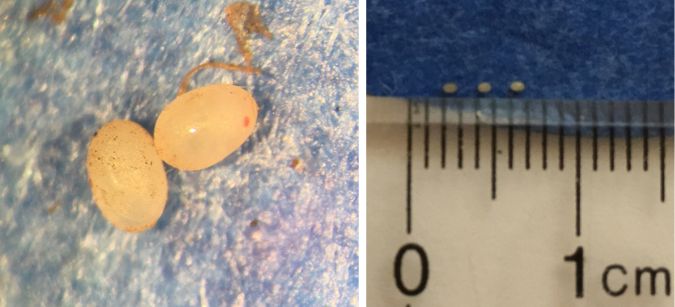

The eggs are approximately 1 mm (0.04 in) in length (Figure 4). They are light yellow to white, with two small red eyespots that will appear as the nymph develops (Aigner et al., 2021). Females can lay an average of 130 eggs per life cycle, with an average of two eggs laid per day (Aigner et al., 2021).

Credit: Mark Abney, University of Georgia

Economic Importance

Damage to peanuts by Pangaeus bilineatus is sporadic but serious when they become abundant in a peanut field, as adults and nymphs feed directly on peanut seeds through the hull. Injury is indicated by scarred yellow and brown lesions on peanut kernels that leave the peanuts unmarketable, leading to commercial-grade reductions (Figure 5). Further, puncture wounds on the peanut hull left by piercing-sucking mouthparts can serve as a pathway for pathogens and aflatoxin contamination. With grade reductions and contamination, a crop can lose value by 50%, and loss can be upwards of $209/Mt ($190/ton) when feeding is present in just 3.5% of the kernels (Mbata and Shapiro-Ilan 2013).

Credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS

Management

Identifying and estimating the population are important steps in developing a proper Integrated Pest Management (IPM) system to control the peanut burrower bug. There are no established economic thresholds or sampling protocols for Pangaeus bilineatus in peanut or any crop. Since they spend most of their time underground, they are difficult to detect, and peanut injury is often unnoticed until after harvest. The only known techniques for sampling these insects are using light traps, pitfall traps, visual inspection of pods, and soil sampling. There are some correlations between light trap/pitfall trap captures of Pangaeus bilineatus and infested peanut fields; however, it is not enough to make management recommendations (Highland and Lummus 1986).

There are few options for managing peanut burrower bugs due to their subterranean nature. There are no current labeled insecticide options that provide adequate control for this pest. Biological control and cultural control are also ineffective. There is relatively little known about the behavior and distribution of any natural predators or parasites that might affect burrower bug populations. However, cultural control practices such as tillage and cover crops may help to reduce burrower bug populations. Conventional tillage significantly reduces burrower bug populations and injury compared to conservation tillage (Chapin et al. 2001). This is likely due to cover crops providing winter habitat for burrower bugs that are still present when peanut is planted. Given the sporadic nature of burrower bug infestations and the benefits of using cover crops and conservation tillage, changing tillage regimes is not recommended.

Selected References

Aigner BL, Crossley MS, Abney MR. 2021. Biology and Management of Peanut Burrower Bug (Hemiptera: Cydnidae) in Southeast U.S. Peanut. Journal of Integrated Pest Management. 12(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/jipm/pmab024

Chapin JW, Dorner JW, Thomas JS. 2004. Association of a Burrower Bug (Heteroptera: Cydnidae) with Aflatoxin Contamination of Peanut Kernels. Journal of Entomological Science 39: 71–83. https://doi.org/10.18474/0749-8004-39.1.71

Chapin JW, Sanders TH, Dean LO, Hendrix, KW, Thomas JS. 2006. Effect of Feeding by a Burrower Bug, Pangaeus bilineatus (Say) (Heteroptera: Cydnidae), on Peanut Flavor and Oil Quality. Journal of Entomological Science 41: 33–39. https://doi.org/10.18474/0749-8004-41.1.33

Chapin JW, Thomas JS, Joost PH. 2001. Tillage and Chlorpyrifos Treatment Effects on Peanut Arthropods—An Incidence of Severe Burrower Bug Injury. Peanut Science 28: 64–73. https://doi.org/10.3146/i0095-3679-28-2-5

Cook JL. 2015. Reevaluation of the Genus Triozocera Pierce (Strepsipera: Corioxenidae) in the United States. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 117 (2): 126–134. https://doi.org/10.4289/0013-8797.117.2.126

GBIF Secretariat. 2023. Pangaeus bilineatus (Say, 1825). GBIF Backbone Taxonomy. Checklist dataset. https://doi.org/10.15468/39omei

(Accessed via GBIF.org on 2025-03-07.)

Gould GE. 1931. Pangaeus uhleri, a pest of spinach. Journal of Economic Entomology 24: 484–486. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/24.2.484a

Froeschner RC. 1960. Cydnidae of the Western Hemisphere. Proceedings of United States National Museum 111: 337–680. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.00963801.111-3430.337

Highland HB, Lummus PF. 1986. Use of light traps to monitor the activity of the burrowing bug, Pangaeus bilineatus (Hemiptera: Cydnidae), and associated field infestations in peanuts. Journal of Economic Entomology 79: 523–526. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/79.2.523

Hites RA. 2021. The Rise and Fall of Chlorpyrifos in the United States. Environmental Science Technology 55: 1354–1358. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c06579

Lis JA, Becker M, Schaefer CW. 2000. Chapter 12: Burrower Bugs (Cydnidae). In Heteroptera of Economic Importance (eds. Schaefer, CW. and Panizzi, AR), pp. 405–406. CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420041859

Mbata GN, Shapiro-Ilan D. 2013. The Potential for Controlling Pangaeus bilineatus (Heteroptera: Cydnidae) Using a Combination of Entomopathogens and an Insecticide. Journal of Economic Entomology 106: 2072–2076. https://doi.org/10.1603/EC13195

Michelotto MD, Bolonhezi D, Freitas RS, Santos JF, Godoy IJ, Schwertner CF. 2021. Population dynamics, vertical distribution and damage characterization of burrower bug in peanut. Scientia Agricola. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-992X-2021-0161

Sailer RI. 1954. Concerning Pangaeus bilineatus (Say) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae, subfamily Cydnidae). Kansas Entomological Society 27: 41–44.

Smith R, Holmes A. 2002. Literature-based key to Florida "burrowing bugs" (Heteroptera: Cydnidae). University of Florida.