Introduction

Lettuce is one of the most important horticultural commodities in Florida state agriculture, with production concentrated in the Everglades agriculture area (EAA) in Palm Beach County (Sandoya and Lu 2024). At the national level, Florida ranks third in lettuce production after California and Arizona. Like many other crops, lettuce production is affected by several insect pests that affect both quality and quantity. This publication introduces some of the common insect pests of lettuce and describes the damage they do to lettuce and lettuce production. Pests described include serpentine leafminers, banded cucumber beetles, aphids, thrips, and caterpillars. This publication is intended for stakeholders in Florida lettuce production, including current and potential lettuce growers, crop consultants, home gardeners, and Extension agents.

Serpentine Leafminer

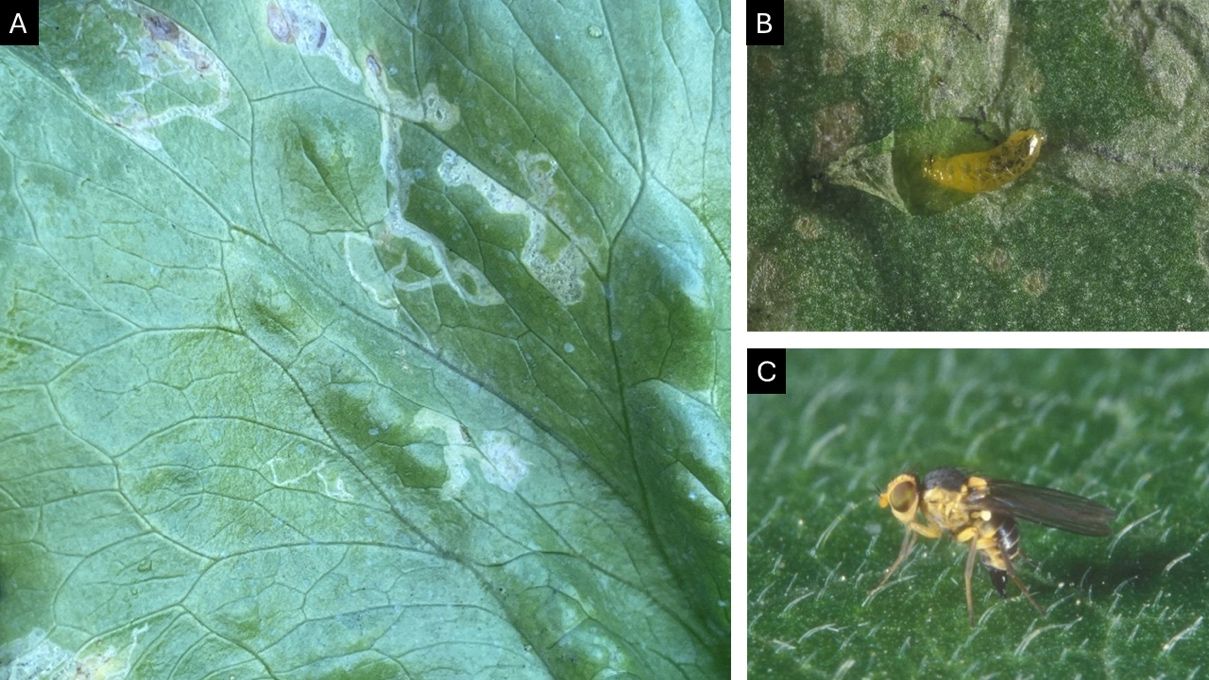

Serpentine leafminers are small insects belonging to the insect order Diptera, family Agromyzidae, and genus Liriomyza. Insects from this family are known for feeding on a variety of crops in the Solanaceae, Fabaceae, Cucurbitaceae, and Asteraceae families, including lettuce. Liriomyza consists of over 400 species, of which 24 are known to cause notable economic damage to crops (Weintraub et al. 2017). Among them, Liriomyza trifolii (Burgess) is an economically important pest species of lettuce that has been reported to cause significant damage and that occurs in high abundance on lettuce farms (Palumbo et al. 1994). Damage caused by leafminers is very distinctive (Figure 1A). Adult females pierce the leaves to lay eggs (Figure 1C) and feed on plant sap from the leaf wounds. The larvae dig tunnels through the leaf tissue, forming a winding trail as they consume the internal parts of the leaf (Figure 1A). While the damage is mainly cosmetic, it can also reduce the plant’s ability to conduct photosynthesis, the process by which plants use energy from the sun to convert carbon dioxide and water into the glucose that allows them to grow. Some leafminer species, such as Liriomyza huibodobrensis (Blanchard) and Liriomyza langei Frick, have been reported to transmit plant viruses such as Tobacco mosaic virus and Sowbane mosaic virus (Costa et al. 1958). Additionally, leafminers can be associated with the transmission of fungal pathogens, such as Alternaria solani (Ellis and Martin) Sorauer, the primary causal agent of early blight in potatoes and tomatoes (Deadman et al. 2002).

Credit: (A) De-Fen Mou, UF/IFAS. (B and C) Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS.

Banded Cucumber Beetle

The banded cucumber beetle, Diabrotica balteata LeConte, belongs to the insect order Coleoptera and the family Chrysomelidae. A distinctive characteristic of the banded cucumber beetle is the green and yellow stripes on its elytra (Figure 2), which are the hardened forewings commonly found on beetles. This insect is considered a significant pest of more than 50 plant species (Huang et al. 2002). It causes direct damage to plants through feeding, as well as indirect damage through the transmission of plant pathogens, such as the Muskmelon necrotic spot virus, to cucurbits (Coudriet et al. 1979). In lettuce, adults feed on the leaves, creating irregular holes, while the larvae feed on the roots, creating entry points for soil-borne pathogens (Huang et al. 2002; Lu et al. 2011; Capinera 2002). The damage caused by the beetle can lead to stunted growth and reduced crop yields.

Credit: Tennyson Bilinkhinyu Nkhoma, UF/IFAS

Aphids

Aphids belong to the insect order Hemiptera and the family Aphididae. They are small, soft-bodied insects that are typically distinguished by a pair of tubular extensions called cornicles (Figure 3). Using their mouthparts, they pierce plant tissue and suck up sap from plants. After they suck up and digest plant sap, aphids secrete a sugary substance known as “honeydew.” This honeydew can foster sooty mold growth, which can cover a plant’s leaves and inhibit the plants’ ability to conduct photosynthesis. In addition to inflicting physical damage through feeding, aphids indirectly damage plants by transmitting more than 275 different plant viruses, more than any other insect group (Hogenhout et al. 2008; Kazak et al. 2015; Nault 1997).

Credit: Tennyson Bilinkhinyu Nkhoma, UF/IFAS

In southern Florida lettuce, the brown lettuce aphid, Uroleucon pseudambrosiae (Olive) (Figure 3), is a common pest. Other aphid species, including the current lettuce aphid Nasonovia ribisnigri (Mosley) and the green peach aphid Myzus persicae (Sulzer), also infest lettuce from seedling to maturity (Liu 2004; McCreight 2008). Notably, M. persicae and N. ribisnigri can transmit lettuce viruses, including Lettuce mosaic virus (Nebreda et al. 2004) and Lettuce necrotic leaf curl virus (Verbeek et al. 2017), respectively.

Thrips

Thrips belong to the order Thysanoptera. Within this order, species in the family Thripidae are known to cause significant damage to agricultural crops. Thrips are tiny, slender insects that are characterized by fringed wings at the adult stage. They are highly adaptable and can feed on a variety of plants, including both crop and non-crop plants (Mound 2005). Thrips have asymmetrical piercing-sucking mouthparts with the left part of the mandible forming a narrow stylet while the right is short or absent (Hunter and Ullman 1992). These mouthparts permit a unique feeding strategy of punching plant tissues and sucking the sap (Nault 1997). Thrips feeding causes physical damage that leads to symptoms such as stippling and leaf silvering, and deposition of fecal materials can cause black spots that can damage leaves (Steenbergen et al. 2020).

Additionally, some thrips species can transmit viruses. Orthotospoviruses are the major virus group transmitted by thrips that can cause significant yield loss in many crops (Rotenberg et al. 2015). For example, Impatiens necrotic spot virus (INSV), a thrips-transmitted orthotospovirus, has caused up to 100% yield losses in California lettuce farms (Hasegawa and Del Pozo-Valdivia 2023). As of May 2025, INSV has not been reported in Florida lettuce. However, its main vector, Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande) (Western flower thrips, Figure 4), is prevalent in the Florida agricultural landscape, including on lettuce farms (Cluever et al. 2018; Riley et al. 2011; Zhao and Rosa 2020). Frankliniella bispinosa Morgan (Florida flower thrips, Figure 5) and Frankliniella schultzei Trybom (common blossom thrips) are two species abundant in lettuce. Other thrips species, including Caliothrips phaseoli (Hood), Thrips palmi Karny (melon thrips), Scirtothrips dorsalis Hood (chilli thrips), and Thrips parvispinus (Karny) (short-spined thrips) were also seen in lettuce fields.

Credit: Tennyson Bilinkhinyu Nkhoma, UF/IFAS

Credit: Yavonne Williams, UF/IFAS

Caterpillars

Caterpillars are the larval stage of insects in the order Lepidoptera, which includes moths and butterflies. Caterpillars inflict damage to plants by feeding on various plant parts (Capinera 2008). In lettuce, these larvae chew large holes in leaves, which reduces photosynthetic capacity, plant growth, and marketability. Common caterpillar species affecting lettuce in Florida include Agrotis ipsilon (Hufnagel) (thread caterpillar, Figure 7); Trichoplusia ni (Hübner) (cabbage looper, Figure 6); Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner) (cotton bollworm); Spodoptera exigua (Hübner) (beet armyworm); and other unidentified species in the Spodoptera genus (Figure 8) (Nuessly and Webb 2003). Additionally, many of these caterpillars are polyphagous and cause significant damage to other vegetable crops such as cabbage and tomatoes, as well as ornamental plants (Akhtar et al. 2012; Jiang et al. 2012).

Credit: J. L. Capinera, UF/IFAS

Credit: John L. Capinera, UF/IFAS

Credit: Tennyson Bilinkhinyu Nkhoma, UF/IFAS

Generalist Beneficial Insects in Lettuce

Not all insects found on crops are pests. Some insects feed on other insects, thereby reducing pest populations. The following are some of the beneficial insects observed in lettuce fields in southern Florida.

Long-Legged Flies

Long-legged flies belong to the insect order of Diptera and the family Dolichopodidae, and there are more than 8,000 species described (Dawah et al. 2020). These insects are small with slender legs, and typically metallic blue, green, or copper (Figure 9). Adult long-legged flies are predacious and prey on soft-bodied arthropods such as thrips, aphids, and mites (Ulrich 2004). Therefore, they are considered beneficial insects in agricultural environments for small insect pest control (Cicero et al. 2017). One of the most common long-legged flies in the EAA is Condylostylus caudatus (Wiedemann) (Figure 9).

Credit: Tennyson Bilinkhinyu Nkhoma, UF/IFAS

Lady Beetles

Lady beetles, also known as ladybugs, ladybirds, and ladybird beetles, belong to the insect order Coleoptera and the family Coccinellidae. They are known for their predatory role in both adult and larval stages (Triplehorn and Johnson 2005), making them beneficial insects in agricultural environments (Figure 10). Most lady beetles are generalist predators, meaning that they can prey on a diverse group of insects, including pests of agricultural crops. They are often used as biological control agents for small insects such as aphids. Lady beetles have a higher predation rate during their larval stage. They can consume larvae of Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, and Hemiptera (Triplehorn and Johnson 2005). Although they are mostly known to feed on foliar arthropods, some studies have found that lady beetles can feed on both foliar and soil-dwelling arthropods, including collembola (Arthropoda: Hexapoda: Collembola) and millipedes (Arthropoda: Myriapoda: Diplopoda) (Kim et al. 2022).

Credit: Tennyson Bilinkhinyu Nkhoma, UF/IFAS

Earwigs

Earwigs belong to the insect order Dermaptera and the family Forficulidae. They are characterized by the forceps-like pincers at the end of their abdomens (Figure 11). Earwigs are generalist predators. They have been reported to prey on a variety of insects, most of which are economically important pests in lettuce production, including Spodoptera spp. (Sueldo et al. 2010) and aphids (Orpet et al. 2019; Bischoff et al. 2024). Most predatory species of earwigs are aggressive hunters; they are often seen jumping in the fields in search of their prey. However, one earwig species, Forficula auricularia L., has been reported to be a pest of citrus crops (Kahl et al. 2022). It is therefore essential to confirm the species of earwigs found in the field to best inform decisions on management or conservation.

Credit: De-Fen Mou, UF/IFAS

Management

Integrated pest management (IPM) is the most effective and sustainable approach for managing lettuce pests. Integrated pest management combines several strategies, including cultural, mechanical, biological, and chemical controls. Cultural methods include crop rotation, weed control, using lettuce cultivars resistant to insect pests, and maintaining field sanitation protocols, all of which aim at reducing the likelihood of pest outbreaks. Mechanical control includes the use of floating row covers or reflective mulches in sandy soil, as well as sticky traps. Biological control involves the conservation of beneficial insects that occur naturally or the introduction of beneficial insects such as lady beetles, parasitoid wasps, and entomopathogenic fungi to the environment. Chemical control methods for lettuce pests are well outlined in the Florida Vegetable Handbook 2025 Chapter 9, Leafy Vegetable Production, published at edis.ifas.ufl.edu and showing labelled pesticides that can be used to control arthropod pests in lettuce (Sandoya-Miranda et al. 2025).

For sustainable lettuce production, IPM strategies are highly recommended for growers. These strategies combine cultural, mechanical, biological, and chemical methods to sustainably control pest populations. If you are not sure what pest problem you have and how to manage the problem, please contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Office. A list is available at sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu.

References

Akhtar, Y., M. B. Isman, L. A. Niehaus, C-H. Lee, and H-S. Lee. 2012. “Antifeedant and Toxic Effects of Naturally Occurring and Synthetic Quinones to the Cabbage Looper, Trichoplusia ni.” Crop Protection 31 (1): 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2011.09.009

Bischoff, R., P. Pokharel, P. Miedtke, H-P. Piepho, and G. Petschenka. 2024. “Environmental Complexity and Predator Density Mediate a Stable Earwig-Woolly Apple Aphid Interaction.” Basic and Applied Ecology 74:108–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2023.12.003

Capinera, J. L. 2002. “Banded Cucumber Beetle, Diabrotica balteata LeConte (Insecta: Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae): EENY-093 IN250, 7 1999.” EDIS 2002 (4). Gainesville, FL. https://doi.org/10.32473/pdf-in250-1999

Cicero, J. M., M. M. Adair, R. C. Adair, W. B. Hunter, P. B. Avery, and R. F. Mizell. 2017. “Predatory Behavior of Long-Legged Flies (Diptera: Dolichopodidae) and Their Potential Negative Effects on the Parasitoid Biological Control Agent of the Asian Citrus Psyllid (Hemiptera: Liviidae).” Florida Entomologist 100 (2): 485–487. https://doi.org/10.1653/024.100.0243

Cluever, J. D., H. A. Smith, J. E. Funderburk, and G. Frantz. 2018. Western Flower Thrips (Frankliniella occidentalis [Pergande]): ENY-883 IN1089, 4 2015.” EDIS 2015 (3). Gainesville, FL. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-in1089-2015

Costa, A. S., D. M. de Silva, and J. E. Duffus. 1958. “Plant Virus Transmission by a Leaf-Miner Fly.” Virology 5 (1): 145–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/0042-6822(58)90011-4

Coudriet, D. L., A. N. Kishaba, and J. E. Carroll. 1979. “Transmission of Muskmelon Necrotic Spot Virus in Muskmelons by Cucumber Beetles.” Journal of Economic Entomology 72 (4): 560–561. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/72.4.560

Dawah, H. A., S. K. Ahmad, M. A. Abdullah, and I. Y. Grichanove. 2020. “The Family Dolichopodidae (Diptera) of the Arabian Peninsula: Identification Key, an Updated List of Species and New Records from Saudi Arabia.” Journal of Natural History 54 (21–22): 1425–1454. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2020.1800118

Deadman, M. L., I. A. Khan, J. R. M. Thacker, and K. Al-Habsi. 2002. “Interactions Between Leafminer Damage and Leaf Necrosis Caused by Alternaria alternata on Potato in the Sultanate of Oman.” The Plant Pathology Journal 18 (4): 210–215. https://doi.org/10.5423/PPJ.2002.18.4.210

Hasegawa, D. K., and A. I. Del Pozo-Valdivia. 2023. “Epidemiology and Economic Impact of Impatiens Necrotic Spot Virus: A Resurging Pathogen Affecting Lettuce in the Salinas Valley of California.” Plant Disease 107 (4): 1192–1201. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-05-22-1248-RE

Hogenhout, S. A., E-D. Ammar, A. E. Whitfield, and M. G. Redinbaugh. 2008. “Insect Vector Interactions with Persistently Transmitted Viruses.” Annual Review of Phytopathology 46 (2008): 327–359. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.phyto.022508.092135

Huang, J., G. S. Nuessly, H. J. McAuslane, and F. Slansky. 2002. “Resistance to Adult Banded Cucumber Beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) in Romaine Lettuce.” Journal of Economic Entomology 95 (4): 849–855. https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-0493-95.4.849

Hunter, W. B., and D. E. Ullman. 1992. “Anatomy and Ultrastructure of the Piercing-Sucking Mouthparts and Paraglossal Sensilla of Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande) (Thysanoptera: Thripidae).” International Journal of Insect Morphology and Embryology 21 (1): 17–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7322(92)90003-6

Kahl, H. M., T. G. Mueller, B. N. Cass, X. Xi, E. Cluff, and J. A. Rosenheim. 2022. “Herbivory by European Earwigs (Forficula auricularia; Dermaptera: Forficulidae) on Citrus Species Commonly Cultivated in California.” Journal of Economic Entomology 115 (3): 852–862. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toac030

Kim, T. N., Y. V. Bukhman, M. A. Jusino, E. D. Scully, B. J. Spiesman, and C. Gratton. 2022. “Using High-Throughput Amplicon Sequencing to Determine Diet Of Generalist Lady Beetles in Agricultural Landscapes.” Biological Control 170:104920. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2022.104920

Liu, Y-B. 2004. “Distribution and Population Development of Nasonovia ribisnigri (Homoptera: Aphididae) in Iceberg Lettuce.” Journal of Economic Entomology 97 (3): 883–890. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/97.3.883

Lu, H., A. L. Wright, and D. Sui. 2011. “Responses of Lettuce Cultivars to Insect Pests in Southern Florida.” HortTechnology 21 (6): 773–778. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTTECH.21.6.773

McCreight, J. D. 2008. “Potential Sources of Genetic Resistance in Lactuca spp. to the Lettuce Aphid, Nasanovia ribisnigri (Mosely) (Homoptera: Aphididae).” HortScience 43 (5): 1355–1358. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.43.5.1355

Mound, L. A. 2005. “Thysanoptera: Diversity and Interactions.” Annual Review of Entomology 50:247–269. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ento.49.061802.123318

Nault, L. R. 1997. “Arthropod Transmission of Plant Viruses: A New Synthesis.” Annals of the Entomological Society of America 90 (5): 521–541. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/90.5.521

Nebreda, M., A. Moreno, N. Pérez, I. Palacios, V. Seco-Fernández, and A. Fereres. 2004. “Activity of Aphids Associated with Lettuce and Broccoli in Spain and Their Efficiency as Vectors of Lettuce mosaic virus.” Virus Research 100 (1): 83–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2003.12.016

Nuessly, G. S., and S. E. Webb. 2002. “Insect Management for Leafy Vegetables (Lettuce, Endive and Escarole): ENY-475 IG161, 7 2002.” EDIS 2002 (6). Gainesville, FL. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-ig161-2002

Orpet, R. J., J. R. Goldberger, D. W. Crowder, and V. P. Jones. 2019. “Field Evidence and Grower Perceptions on the Roles of an Omnivore, European Earwig, in Apple Orchards.” Biological Control 132:189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2019.02.011

Palumbo, J. C., C. H. Mullis, Jr., and F. J. Reyes. 1994. “Composition, Seasonal Abundance, and Parasitism of Liriomyza (Diptera: Agromyzidae) Species on Lettuce in Arizona.” Journal of Economic Entomology 87 (4): 1070–1077. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/87.4.1070

Sandoya, G., and H. Lu. 2024. Evaluation of Lettuce Cultivars for Production on Muck Soils in Southern Florida. HS1225. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/HS1225

Sandoya-Miranda, G., R. Kanissery, N. S. Dufault, et al. 2025. “Chapter 9. Leafy Vegetable Production.” In Vegetable Production Handbook of Florida, 2024–2025. HS728. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/CV293

Steenbergen, M., C. Broekgaarden, C. M. J. Pieterse, and S. C. M. Van Wees. 2020. “Bioassays to Evaluate the Resistance of Whole Plants to the Herbivorous Insect Thrips.” In Jasmonate in Plant Biology: Methods and Protocols, edited by A. Champion and L. Laplaze. New York, NY: Springer US. (Methods in Molecular Biology). P. 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-0142-6_7

Triplehorn, C. A., and N. F. Johnson. 2005. Borror and DeLong’s Introduction to the Study of Insects, 7th edition. Thomson Brooks/Cole, Blemont, CA. P. 433.

Ulrich, H. 2004. “Predation by Adult Dolichopodidae (Diptera): A Review of Literature with an Annotated Prey-Predator List.” Studia Dipterologica 11 (2): 369–403. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20053147038

Verbeek, M., A. M. Dullemans, and R. A. A. van der Vlugt. 2017. “Aphid Transmission of Lettuce necrotic leaf curl virus, a Member of a Tentative New Subgroup within the Genus Torradovirus.” Virus Research. 241:125–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2017.02.008

Weintraub, P. G., S. J. Scheffer, D. Visser, et al. 2017. “The Invasive Liriomyza huidobrensis (Diptera: Agromyzidae): Understanding Its Pest Status and Management Globally.” Journal of Insect Science 17 (1): 28. https://doi.org/10.1093/jisesa/iew121

Zhao, K., and C. Rosa. 2020. “Thrips as the Transmission Bottleneck for Mixed Infection of Two Orthotospoviruses.” Plants 9 (4): Article 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9040509