Introduction

The “One Health” approach is a framework for wellbeing that recognizes the interconnection and co-dependence of human, animal, plant, and environmental health. One Health focuses on collaborating across scientific fields to improve health and wellbeing across all components of the ecosystem (Adisasmito et al. 2022). While the core concepts behind One Health are not new, the framework was formalized in the early 2000s, after the first cases of severe acute respiratory disease (SARS) and the rapid spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1. These events drew international attention and concern about how pathogens can move and spread across the human, animal, and environmental interface and highlighted the need for collaborative efforts to address these diseases in an increasingly connected world (Evans and Leighton 2014; Mackenzie et al. 2014). The One Health framework is now used broadly when working to address health challenges across human, animal, and plant systems. This publication is intended to provide information about One Health to researchers and stakeholders in mosquito control and public health professions and to the general public.

Key Principles of One Health

One Health aims to develop interdisciplinary prevention and mitigation strategies to address health problems more effectively. To achieve this goal, the approach implements a range of fundamental principles and strategic goals (Adisasmito et al. 2022; Cook et al. 2004; Gruetzmacher et al. 2021), which can be summarized into four broad categories:

- Interconnectedness of Health

People, animals, and the environment are closely linked, and the health of one affects and depends on the health of the others

- Collaboration and Cooperation

Tackling health challenges requires teamwork across sectors and at every level of society. Efforts must be combined across disciplines and areas of expertise and must consider all forms of knowledge and perspectives to improve overall wellbeing and effectively address health risks across sectors.

- Prevention and Preparedness

A focus on surveillance, early detection and intervention, and efforts to better understand pathogens that cause diseases and their transmission is key to mitigating and preventing health issues that impact humans, animals, plants, and the environment.

- Sustainability

Long-term solutions are needed to effectively address and improve the overall health of the planet and the lives, livelihoods, and wellbeing of current and future generations.

One Health across Sectors

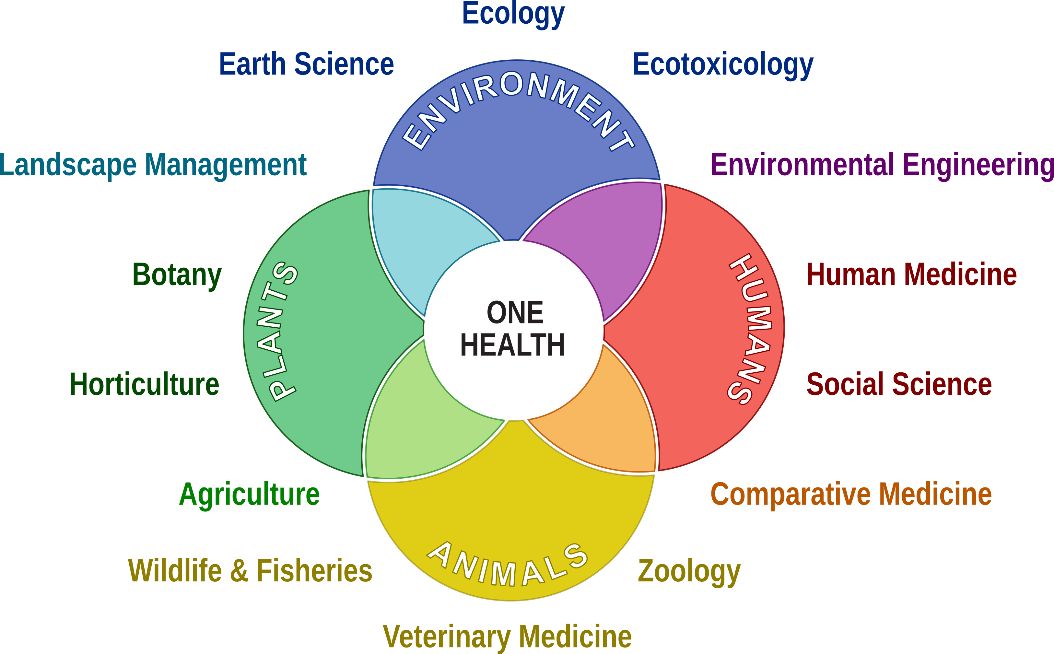

Rapid human population growth and increased human activities across environments have resulted in large-scale landscape transformation and increased connectivity through global trade and movement (Zhang et al. 2022). All of these factors impact the intersection of humans, animals, plants, and the overall environment, which can result in unexpected outcomes, including changes in distributions of species that can transmit pathogens. This creates new, often complex health threats that require collaboration among experts from multiple disciplines and sectors to develop effective mitigation plans. These disciplines and sectors can include human and veterinary medicine, ecology and land management, and social science and economic policy, among others, and range from local to international cooperation (Barrett and Osofsky 2013). Together, experts from varied backgrounds work to address challenges such as zoonotic diseases, which are infectious diseases that are transmitted between animals or between animals and humans; food and water safety; antimicrobial resistance, which can occur when antibiotics are no longer effective in treating a bacterial infection; and the environmental conditions that affect wellbeing (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The One Health framework showing the intersection of human, animal and plant, and environmental health, and examples of disciplines and sectors that work in different combinations together to address problems.

Credit: Amely Bauer, UF/IFAS, modified from Barcaccia et al. 2020 and Falkenberg et al. 2022

Case Study: The One Health Response to West Nile virus

One example demonstrating a One Health approach is the collaborative response to the arrival and emergence of West Nile virus in the United States (Barrett et al. 2011). West Nile virus is a mosquito-borne virus that is maintained in birds but can also cause disease in humans and other animals, especially horses. In the late summer of 1999, physicians in New York City noticed a cluster of patients with severe encephalitis (inflammation of the brain). Around the same time, pathologists and epidemiologists were investigating an unusually high number of dead birds, especially crows, in and around the city. Within one month after the first human cases were reported to health authorities, molecular analyses and other laboratory tests confirmed that West Nile virus was present in both birds and humans, as well as in mosquitoes, confirming it had entered the United States (Barrett et al. 2011; Sejvar 2003). This example demonstrates that effective communication across sectors and disciplines can result in the correct identification of a disease-causing agent. Since then, West Nile virus has become the leading cause of arboviral diseases in the United States (CDC 2024b). (Arboviruses are diseases caused by viruses transmitted by arthropod vectors.) West Nile virus highlights the ongoing need for collaboration among scientists, public health officials, land managers, and mosquito control experts. Effective response to the emergence of West Nile virus in the United States has required collaboration across sectors. The various scientific disciplines and experts listed continue to work together in myriad different combinations to address the problem.

Environmental Disciplines

Ecology

Environmental science

Environmental engineering

Agricultural science

Environmental policy

Urban planning

Mosquito control

Human-Focused Disciplines

Medicine

Epidemiology

Public health

Global health

Nursing

Microbiology

Public policy

Pharmacology

Wildlife-Focused Disciplines

Wildlife biology

Veterinary medicine

Conservation biology

Conservation medicine

Disease ecology

Ornithology

Zoology

Disciplines Dealing with Domestic Animals

Veterinary medicine

Epidemiology

Agricultural science

Animal husbandry

Pharmacology

Microbiology

One Health in Action

To date, the most common examples of One Health in action have been responses to the emergence of pathogens spread by animals and insects to humans and livestock. Human health and veterinary health sectors had strong influence over the original One Health concept (Destoumieux-Garzón et al. 2018). However, the One Health approach is also applicable to a wide range of other health issues, including antimicrobial resistance, food safety, food security, and environmental risks to health (Garcia et al. 2020; Hoffmann et al. 2022; WHO 2022). For example, the One Health approach has been used to identify the source and mitigate the risk of food-borne illness caused by the bacterium Escherichia coli. This bacterium can contaminate leafy greens and has been linked to manure from cattle grazing near lettuce fields (CDC 2025). The One Health framework also facilitated the discovery that excessive use of pesticides and fertilizers both harmed animal health in Indian dairies and led to high pesticide levels in milk consumed by humans. In another case, a team that included scientists from several organizations found that toxins from a harmful algal bloom in a lake flowing into Monterey Bay were causing many California sea otter deaths. This prompted the CDC to launch the One Health Harmful Algal Bloom System, which helps collect data to better understand these algal blooms and prevent negative effects on humans, animals, and the overall environment (CDC 2024a).

One Health and IPM

Multiple parallels exist between the One Health framework and Integrated Pest Management (IPM) (Falkenberg et al. 2022). IPM is an approach to controlling pest species that uses a combination of evidence-based methods, including biological, cultural, physical, and chemical tools, to manage pest species in a way that is sustainable and minimizes harm (USDA 2024). Like the One Health framework, IPM requires coordination across disciplines and sectors to find and apply the most effective solutions to current challenges. Coordination and cooperation among sectors has assisted with identification and management of invasive pest species and plant pathogens, as well as with work to mitigate the impacts of global environmental change on agricultural production. The similarities between the two frameworks make integration of One Health and IPM a logical next step toward improving wellbeing (Falkenberg et al. 2022). One promising approach to integrating One Health and IPM is sustainable agricultural intensification. This approach promotes planting a diversity of agricultural crops, which supports ecosystem services that protect human and animal health while still producing crop yields needed for food security (Falkenberg et al. 2022).

Economic Considerations

The estimated financial benefits of One Health are substantial. The World Bank estimates that preventing disease outbreaks, protecting ecosystems, and ensuring a stable food supply can save governments and industries billions of dollars in healthcare costs, lost productivity, and the costs associated with mounting emergency responses (Berthe et al. 2018). For example, the yearly global estimated cost of preventing pandemics amounts to approximately one-third of the estimated cost of managing and responding to them (World Bank 2022). In addition, considering costs that are both direct (e.g., costs for medical treatment) and indirect (e.g., revenues lost because of the harmful effects of disease on the workforce or tourism) the World Bank estimated that One Health has an expected benefit to the global community that is worth at least US$ 37 billion each year (World Bank 2022; WHO 2023). These estimates are further supported by a growing body of evidence showing direct economic benefits from implementing the One Health framework (Auplish et al. 2024; Frank and Sudarshan 2024).

Who has adopted the One Health framework?

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), cdc.gov

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), usda.gov

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), unep.org

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), fao.org

- World Health Organization (WHO), who.int

- World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), woah.org

- World Bank Group, worldbank.org

How can the public participate in the One Health framework?

Find new ways to monitor and record biodiversity in your neighborhood, town, or broader areas using community science apps, such as iNaturalist.org, the Cornell Lab’s eBird.org, or globe.gov’s NASA Globe Observer Mosquito Habitat Mapper. These records help scientists understand where organisms are distributed and when they are active, and this information can be used to improve our understanding of how biodiversity, human health, and animal and plant health are interconnected on the planet.

Summary

The One Health approach provides an integrative framework to improve health and wellbeing across human, animal, and plant populations, and throughout the broader environment. This framework encourages communication across sectors and disciplines to develop effective and sustainable approaches to new and existing health challenges. Multiple agencies have already adopted a One Health approach within their organizations, and new opportunities to combine concepts from IPM, as well as broader community participation, will continue to expand applications of this approach across sectors.

References

Adisasmito, W. B., S. Almuhairi, C. B. Behravesh, et al. 2022. “One Health: A New Definition for a Sustainable and Healthy Future.” PLoS Pathogens 18 (6): e1010537. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1010537

Auplish, A., E. Raj, Y. Booijink, et al. 2024. “Current Evidence of the Economic Value of One Health Initiatives: A Systematic Literature Review.” One Health 18:100755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2024.100755

Barcaccia, G., V. D’Agostino, A. Zotti, and B. Cozzi. 2020. “Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 on the Italian Agri-Food Sector: An Analysis of the Quarter of Pandemic Lockdown and Clues for a Socio-Economic and Territorial Restart.” Sustainability 12 (14): 5651. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145651

Barrett, M. A., T. A. Bouley, A. H. Stoertz, and R. W. Stoertz. 2011. “Integrating a One Health Approach in Education to Address Global Health and Sustainability Challenges.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 9 (4): 239–245. https://doi.org/10.1890/090159

Barrett, M. A., and S. A. Osofsky. 2013. “One Health: Interdependence of People, Other Species, and the Planet.” In Jekel’s Epidemiology, Biostatistics, Preventive Medicine, and Public Health, 4th edition (pp. 364–377), edited by D. L. Katz, J. G. Elmore, D. Wild, and S. C. Lucan. Elsevier. https://wildlife.cornell.edu/sites/default/files/2018-10/OneHealthCh_JekelEpi%26PublicHealth%20copy.pdf

Berthe, F. C. J., T. Bouley, W. B. Karesh, et al. 2018. Operational Framework for Strengthening Human, Animal and Environmental Public Health Systems at Their Interface. World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/703711517234402168

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2024a. One Health: Poisoned Sea Otters in California. https://www.cdc.gov/one-health/php/stories/poisoned-sea-otters.html

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2024b. West Nile virus: About West Nile. https://www.cdc.gov/west-nile-virus/about/index.html

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2025. Saving Lives by Taking a One Health Approach: Connecting Human, Animal, and Environmental Health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, One Health Office. https://www.cdc.gov/one-health/media/pdfs/OneHealth-FactSheet-FINAL.pdf

Cook, R. A., W. B. Karesh, and S. A. Osofsky. 2024. “The Manhattan Principles” proceeds of the One World, One Health: Building Interdisciplinary Bridges to Health in a Globalized World symposium. Wildlife Conservation Society and The Rockefeller University. https://oneworldonehealth.wcs.org/About-Us/Mission/The-Manhattan-Principles.aspx

Destoumieux-Garzón, D., P. Mavingui, G. Boetsch, et al. 2018. “The One Health Concept: 10 Years Old and a Long Road Ahead.” Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 5:14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2018.00014

Evans, B. R., and F. A. Leighton. 2014. “A history of One Health.” Revue Scientifique et Technique (International Office of Epizootics) 33 (2): 413–420. https://doi.org/10.20506/rst.33.2.2298

Falkenberg, T., S. Ekesi, and C. Borgemeister. 2022. “Integrated Pest Management (IPM) and One Health—a Call for Action to Integrate.” Current Opinion in Insect Science 53:100960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2022.100960

Frank, E., and A. Sudarshan. 2024. “The Social Costs of Keystone Species Collapse: Evidence from the Decline of Vultures in India.” American Economic Review 114 (10): 3007–3040. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20230016

Garcia, S. N., B. I. Osburn, and M. T. Jay-Russell. 2020. “One Health for Food Safety, Food Security, and Sustainable Food Production.” Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 4: Article 1. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2020.00001

Gruetzmacher, K., W. B. Karesh, J. H. Amuasi, et al. 2021. “The Berlin Principles on One Health—Bridging Global Health and Conservation.” The Science of the Total Environment 764:142919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142919

Hoffmann, V., B. Paul, T. Falade, et al. 2022. “A One Health Approach to Plant Health.” CABI Agriculture and Bioscience 3:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43170-022-00118-2

Mackenzie, J. S., M. McKinnon, and M. Jeggo. 2014. “One Health: From Concept to Practice.” In Confronting Emerging Zoonoses (pp. 163–189), edited by A. Yamada, L. H. Kahn, B. Kaplan, T. P. Monath, J. Woodall, and L. Conti. Springer Japan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-55120-1_8

Sejvar, J. J. 2003. “West Nile virus: An Historical Overview.” The Ochsner Journal 5 (3): 6–10. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3111838/

USDA (United States Department of Agriculture). 2024. Integrated Pest Management. https://www.usda.gov/about-usda/general-information/staff-offices/office-chief-economist/office-pest-management-policy-opmp/integrated-pest-management

WHO (World Health Organization). 2022. A health perspective on the role of the environment in One Health. WHO Regional Office for Europe. https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-2022-5290-45054-64214

WHO (World Health Organization). 2023. One Health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/one-health

World Bank. 2022. Putting Pandemics Behind Us: Investing in One Health to Reduce Risks of Emerging Infectious Diseases. https://doi.org/10.1596/38200

Zhang, L., M. Xu, H. Chen, Y. Li, and S. Chen. 2022. “Globalization, Green Economy and Environmental Challenges: State of the Art Review for Practical Implications.” Frontiers in Environmental Science 10: Article 870271. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.870271