The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

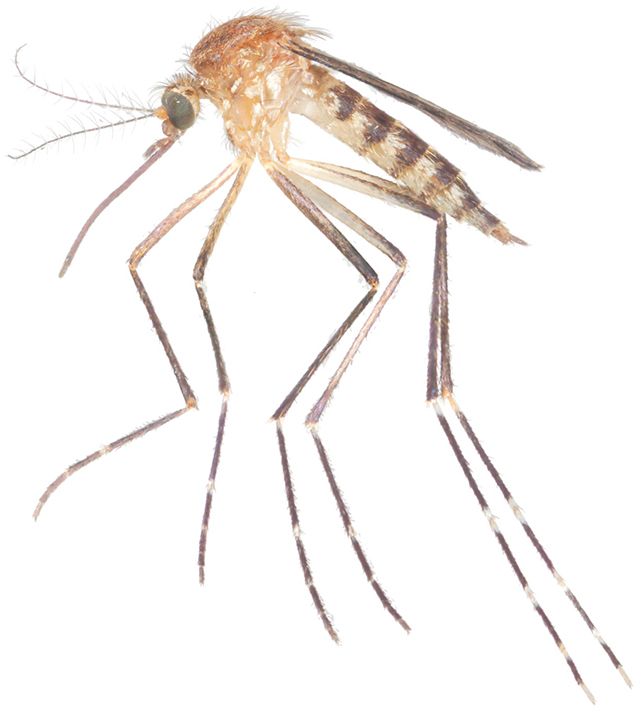

Aedes canadensis (Figure 1) was first described by Frederick V. Theobald as Culex canadensis in the early twentieth century (Theobald 1901) but was later transferred to the genus Aedes (Freitas and Bartholomay 2021). It was subsequently moved to the genus Ochlerotatus as part of a reclassification of the mosquito tribe “Aedini” (Reinert 2000) and eventually restored to the genus Aedes after a taxonomic reclassification (Wilkerson et al. 2015). Aedes canadensis is a woodland mosquito that is widely distributed in North America (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955). It has one generation per year and is notable for the long period of dormancy of its eggs, lasting through the summer, fall, and winter (Magnarelli 1977). It is regarded as a minor nuisance species that is capable of spreading multiple human and animal pathogens.

Credit: Nathan Burkett-Cadena, UF/IFAS

A geographical variant of this species is present in the southern United States. This variant of Aedes canadensis was originally described as Aedes mathesoni by Middlekauff in 1944. It is distinguished by subtle differences in the coloration of its thorax and hindlegs (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955) and is indigenous to parts of Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida. Aedes mathesoni was later reclassified as a subspecies of Aedes canadensis (Rings and Hill 1948, Darsie and Ward 2005) but is now considered to be a geographical variant of Aedes canadensis (Harbach and Wilkerson 2023). No genetic studies have been conducted as of May 2025 to examine if these geographic variants within Aedes canadensis are associated with any genetic variations (data source: GenBank).

Distribution

Aedes canadensis is found throughout most of Canada, as well as in the eastern, midwestern, and southern United States (Figure 2) (Darsie and Ward 2005). It has also been reported from Mexico and the Dominican Republic, although no locality data is available (Harbach and Wilkerson 2023).

Credit: Data from Darsie and Ward 2005

Morphology

Adult

Aedes canadensis is a medium-sized, dark brown mosquito, with hind legs that appear banded, even to the naked eye (Figure 3). The dorsal aspect of the head bears a large patch of narrow, pale yellow scales, and the lateral aspects bear broad, white scales (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955). The proboscis and palps (fingerlike appendages of the mouthparts) are entirely dark scaled (Harrison et al. 2016; Figure 1).

The wings of this species range in length from 3.2–4 mm (0.13–0.16 in) and have narrow, dark scales (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955). The upper (dorsal) surface of the thorax (called the scutum) is brown and is clad in golden-brown scales that do not form a distinctive pattern (Figure 4). Grayish-white scales are present in patches on the sides of the thorax (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955; Figure 1).

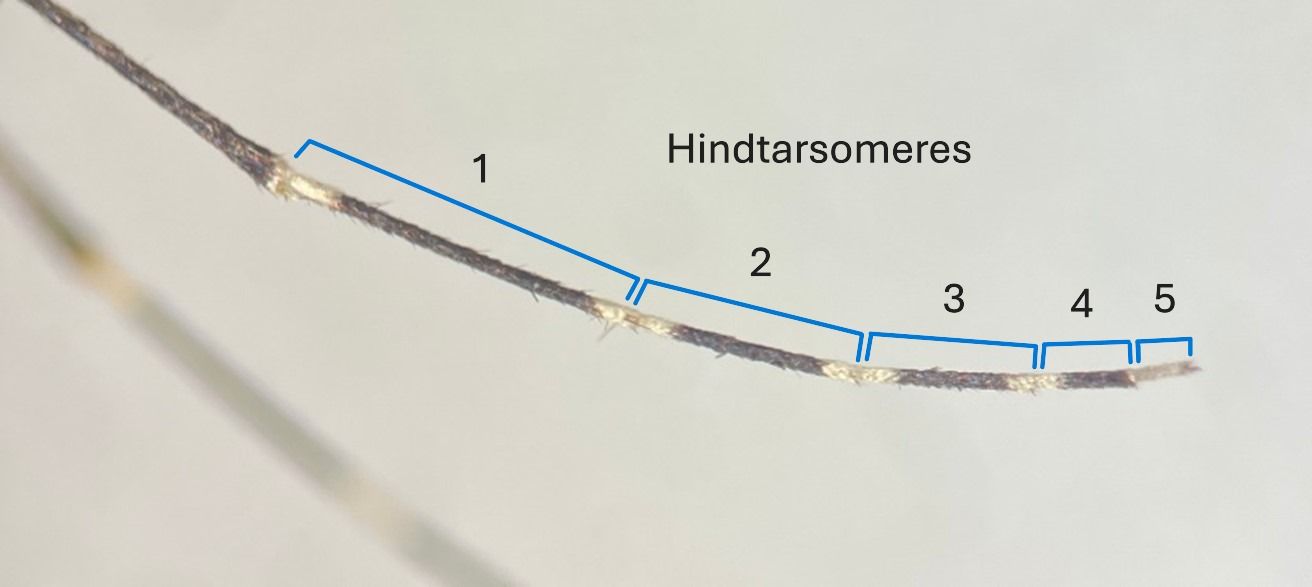

The upper two leg segments (femur and tibia) are mostly dark, with pale coloration on the rear side of each segment (Figure 1). There is a pale knee spot on the distal end of each femur, and each tibia bears pale scales at its base and apex (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955). On the hindlegs, the upper and lower margins of the first-fourth tarsomeres (lower leg segments) bear pale bands (Figure 3) (Darsie and Ward 2005). The terminal segment (fifth tarsomere) of each hindleg is entirely pale scaled in Aedes canadensis (Theobald), and dark scaled in Aedes canadensis var. mathesoni.

The dorsal (upper) portion of the first abdominal segment is dark with scattered white scales. The dorsal portion of the other abdominal segments bears a narrow pale band on the margin of the segment closest to the thorax. This band widens into large pale patches on either side of the segment. The sixth and seventh abdominal segments typically have a thin strip of white scales at their apex (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955). The underside of the abdomen is usually pale but dark scales may be present on the margin of each segment farthest from the thorax (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955).

Credit: Bryna Wilson, UF/IFAS

Credit: Bryna Wilson UF/IFAS

Egg

The egg of Aedes canadensis is dark brown, measuring between 630–758 µm (0.025–0.030 in) in length and 180–206 µm (0.007–0.008 in) in width (Kalpage and Brust 1968). It is spindle-shaped appearing rounded at the anterior end and tapered at the posterior end (Kalpage and Brust 1968).

Larva

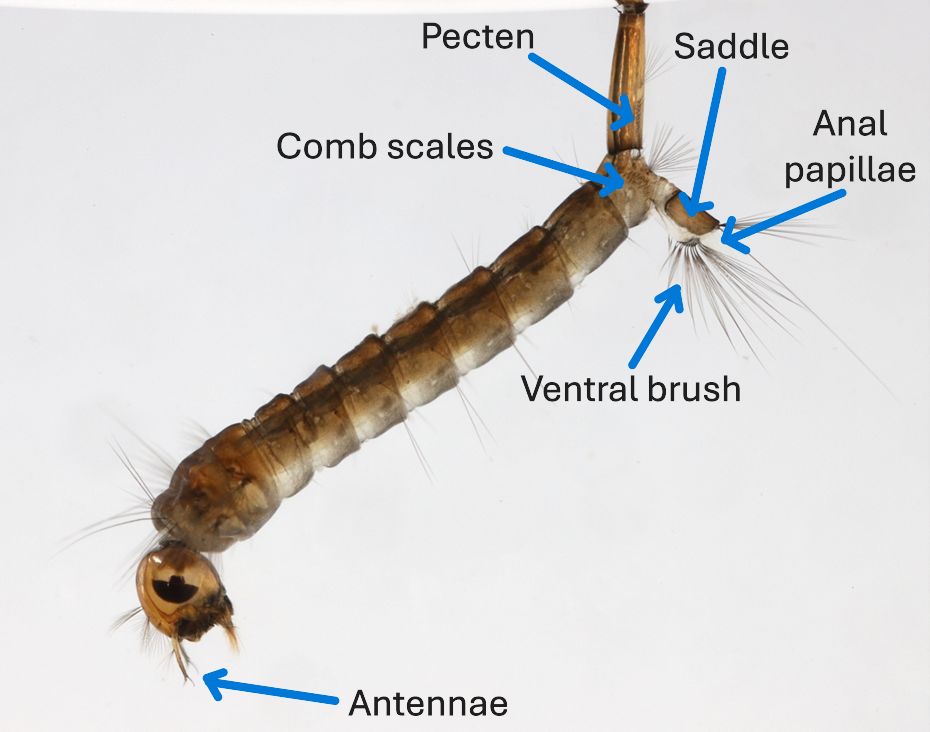

The fully developed larva of Aedes canadensis is medium-sized and often brown in color (Figure 5). Its head is wider than long, with the widest part in the posterior half. The antennae on its head are half the length of the head and covered in small spines. A tuft of setae arises near the middle of each antenna (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955).

The eighth abdominal segment bears a cluster of pointed scales, called comb scales. Each comb scale is fringed with thin spines that are similar to each other in length (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955).

The siphon is moderately long, slightly wider at its base than its apex, and has a single pair of branched setae arising near its middle (Figure 6). The basal half of the siphon bears a row of 13–24 spines (called the pecten) (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955). The spines of the pecten are similar to one another and more or less evenly spaced. The siphon is three to four times longer than it is wide (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955).

The terminal abdominal segment bears a darkened dorsal plate, called a saddle, that does not completely encircle the segment (Darsie and Ward 2005). The terminal abdominal segment also bears a large cluster of fanlike setae (called the ventral brush) and has anal papillae that measure 1–1.7 times the length of the saddle (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955).

Credit: Nathan Burkett-Cadena, UF/IFAS

Credit: Nathan Burkett-Cadena, UF/IFAS

Pupa

Mosquito pupae have comma-shaped bodies consisting of a cephalothorax and abdomen. Compound eyes and tubular respiratory organs called trumpets arise laterally on the anterior portion of the cephalothorax (Yamany et al. 2024). The abdomen has nine distinct segments, each of which has dorsal (tergal) and ventral (sternal) sclerites (Yamany et al. 2024). The terminal abdominal segment bears a locomotory structure called the paddle. The presence, length, position, and branching of the setae on the cephalothorax and abdomen are used to identify pupae to genus and species (Darsie 2005). The pupa of Aedes canadensis can be differentiated from other Aedes pupae by minor differences in the branching of setae on its cephalothorax and abdominal segments (Darsie 2005).

Life Cycle

Aedes canadensis is a univoltine species, meaning that it undergoes only one generation per year (Crans 2004). In Canada and the northern United States, the adults emerge primarily between April and June (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955), and peak adult abundance occurs in June and July (Andreadis et al. 2014, Shahhosseini et al. 2021). The timing of life stages in the southern United States has not been reported in the literature and may differ from the patterns observed in the northern United States. In the southern states, the abundance of adult Aedes canadensis has been observed to peak in the spring and they are rarely encountered in the summer or fall (Burkett-Cadena, personal observation).

Aedes canadensis is an early-breeding mosquito, mating soon after the adults emerge (Berry et al. 1986). Males remain near their larval habitats and die soon after mating (Magnarelli 1977), but females persist for several months before dying off (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955). In the northern United States and Canada, egg laying occurs at the edges of woodland bodies of water in late spring or early summer (Mallack et al. 1964).

Warmth induces Aedes canadensis eggs to enter a state of diapause that will end only after they have been chilled or frozen (Mallack et al. 1964). Thus, the eggs remain dormant for the remainder of the year and begin to hatch in the early spring when they are inundated with water from melting snow or spring rain (Magnarelli 1977). Large numbers of larvae may be present in woodland bodies of water as early as the beginning of March and persist through the end of May (Crans 2015). In addition to temporary vernal pools, larvae may be found near the surface of the water in small ponds, puddles, marshes, and pools ranging from 3 inches to 2 feet deep (Jenkins and Knight 1952).

The mosquito species that share larval development habitat with Aedes canadensis vary depending on location and season. In New York State, Aedes canadensis larvae often develop alongside larvae of Aedes abserratus, Aedes punctor, Aedes trichurus, Aedes stimulans, Aedes excrucians, and Aedes fitchii, and may also be found with Culex restuans and Culex territans during the summer (Magnarelli 1977). In New Jersey, Aedes canadensis has been found to be associated in the spring with Aedes stimulans, Aedes grossbecki, and Aedes excrucians, and in the summer with Aedes cinereus, Aedes sticticus, Aedes vexans, Aedes atlanticus, and Psorophora ferox (Crans 2015). In Pennsylvania, mid-summer Aedes canadensis larvae have been found to share habitat with Aedes vexans, Aedes trivittatus, Culex restuans, Culex territans, and Psoropjora ferox (Wills and Fish 1973). Aedes canadensis generally inhabits shallower areas of water bodies than the larvae of these other species (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955). No habitat associations data specific to the southern United States is available for this species.

Aedes canadensis eggs that remain above water level throughout the spring may hatch in midsummer or early fall if heavy rainfall floods woodland pools or creates temporary puddles. This second hatching is responsible for the midsummer spikes in Aedes canadensis abundance that have been observed in Wisconsin and New York (Magnarelli 1977). It is also thought that fall hatching may occasionally be from newly laid eggs, rather than eggs that have overwintered (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955).

Hosts

Aedes canadensis feeds from dawn to dusk, with peak activity around 8:00 p.m. (Sherwood et al. 2020, Trueman and McIver 1986). Its daily activity pattern does not exhibit any predictable seasonal variations (Trueman and McIver 1986). Although this species is mainly encountered in forest habitats, it can also be found in suburban areas (Cloutier et al. 2021), where it can be a significant biting nuisance to humans and domestic animals, particularly in shaded areas (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955).

Aedes canadensis is known to feed upon mammals, birds, and reptiles, and seems to prefer one host group over the others in different regions within its range. In a study conducted in Connecticut, USA, for example, Aedes canadensis took 93% of blood meals from just one host species (white-tailed deer), with the remaining 7% of bites on humans, house cats, opossum, American woodcocks, and turtles (Molaei et al. 2008). A similar propensity for favoring mammals was observed in a Canadian study, in which 62% of Aedes canadensis blood meals were from mammals (26% deer, 12% wild boar, 12% humans, 12% wolves) and 38% were from American crows (Shahhosseini et al. 2021). A study of Aedes canadensis host associations further south (in North Carolina) found that turtles are the preferred hosts for this species (Irby and Apperson 1988). In this study, 15% of the blood-fed Aedes canadensis females had fed on mammals (primarily deer) and 85% had fed on turtles (Irby and Apperson 1988). It was previously documented that Aedes canadensis is highly attracted to tethered Eastern box turtles in New Jersey and is the primary mosquito species that feeds on them (Crans and Rockel 1968). Thus, it is possible that Aedes canadensis may feed predominantly on turtles when they are readily available (as the Eastern box turtle is in North Carolina).

Medical and Veterinary Importance

Multiple studies have implicated Aedes canadensis in the transmission of the California serogroup of encephalitis viruses (Bunyaviridae: Orthobunyavirus), which includes La Crosse encephalitis virus, Jamestown Canyon virus, and snowshoe hare virus (Snyman et al. 2023). These viruses circulate in populations of wild mammals but sometimes cause disease in humans. Infected humans are often asymptomatic, but may experience mild to severe neurological symptoms, occasionally leading to death (Webster et al. 2017).

Aedes canadensis has been shown to carry La Crosse encephalitis virus in Ohio (Berry et al. 1986), and homogenized field-collected specimens from West Virginia have also tested positive for the virus (Nasci et al. 2000). This virus primarily infects small mammals such as chipmunks, which are abundant in the woodland habitat of Aedes canadensis. Aedes triseriatus is known to be the primary mosquito species involved in the transmission of La Crosse encephalitis virus (Harris et al. 2015), but Aedes canadensis may also play a role in transmitting the virus between wild animals and could potentially spread La Crosse to humans.

Jamestown Canyon virus has frequently been detected in Aedes canadensis in Connecticut, and it has been confirmed that Aedes canadensis can transmit it under laboratory conditions (Andreadis et al. 2008). Since Aedes canadensis feeds heavily on white-tailed deer (Molaei et al. 2008), which are the species most frequently infected with Jamestown Canyon virus, it is strongly suspected of being able to spread Jamestown Canyon Virus in the wild. A number of other species of Aedes, Anopheles, Culex, Culiseta, and Coquillettidia mosquitoes are also suspected of carrying Jamestown Canyon virus.

Snowshoe hare virus is spread by Culiseta inornata, Culiseta impatiens, and multiple species of Aedes (Walker and Yuill 2023). Like La Crosse encephalitis virus, this pathogen circulates among small woodland mammals, which are frequently bitten by Aedes canadensis. The virus has been detected in homogenized field-collected Aedes canadensis in the Yukon (McLean et al. 1974) and in Newfoundland (Carson et al. 2017). These studies indicate that Aedes canadensis may play a role in spreading Snowshoe hare virus.

Aedes canadensis is known to transmit the dog heartworm parasite, Dirofilaria immitis (Bickley et al. 1977). In the northern United States, it is one of several mosquito species responsible for transmitting Cache Valley Virus between white-tailed deer (Andreadis et al. 2014). It is also thought to spread Eastern Equine Encephalitis virus by feeding on humans after biting infected birds (Sherwood et al. 2020). Additionally, some researchers have suggested that Aedes canadensis may contribute to the transmission of West Nile virus, a pathogen that is spread primarily by Culex mosquitoes (Giordano et al. 2018).

Surveillance

In the eastern and midwestern United States, surveillance of Aedes canadensis is particularly important in spring and late summer, when Jamestown Canyon virus and La Crosse virus cases peak, respectively (Coleman et al. 2021, Vahey et al. 2021). Carbon dioxide-baited CDC light traps are an accessible and highly effective means of trapping Aedes canadensis (NJ Department of Health 2024).

Management

The management of Aedes canadensis in its preferred habitat (forests and wetlands) is complicated by the need to balance the environmental risks of treatment with the risks of allowing the population to persist unchecked. Wetlands are protected by law and contain a rich variety of species that may be harmed by frequent applications of insecticides to target Aedes canadensis (Rey et al. 2012). Since Aedes canadensis is not the primary species responsible for transmitting human diseases of concern, it is infrequently targeted for management. Instead, its populations are reduced inadvertently when mosquito control districts treat forest and wetland areas to target high-priority disease-spreading species such as Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus.

Ultra-low volume applications of organophosphates and pyrethroids are the standard method of decreasing populations of adult mosquitoes in large outdoor areas (Kaura et al. 2022). Since Aedes canadensis is active throughout the day, adulticide applications that occur during daylight hours can be expected to reduce their population along with that of the target species (Sherwood et al. 2020).

Temephos is currently the preferred organophosphate larvicide for use in wetland areas (Rey et al. 2012), and it demonstrates broad-spectrum efficacy against many mosquito species (Martínez-Mercado et al. 2022). Additionally, the larvicides Bti and methoprene are commonly used to target a variety of mosquito species and are known to be effective against Aedes canadensis. Field applications of Bti can reduce Aedes canadensis larval populations in woodland pools by 98% (Wilmot et al. 1993). Similarly, aerially applied methoprene has been shown to produce an 80% reduction in Aedes canadensis larvae in flooded woodlots (McCarry 1996).

Concluding Remarks

Aedes canadensis is a widespread North American mosquito that hatches from woodland bodies of water in the early spring and midsummer. It feeds on mammals and spreads dog heartworm parasites and several arboviruses. Although it is not often specifically targeted for management, adulticidal and larvicidal strategies used to control other mosquito species can aid in reducing populations of Aedes canadensis.

References

Andreadis TG, Anderson JF, Armstrong PM, Main AJ. 2008. Isolations of Jamestown Canyon virus (Bunyaviridae: Orthobunyavirus) from field-collected mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in Connecticut, USA: a ten-year analysis, 1997–2006. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 8: 175–188. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2007.0169

Andreadis TG, Armstrong PM, Anderson JF, Main AJ. 2014. Spatial-Temporal Analysis of Cache Valley Virus (Bunyaviridae: Orthobunyavirus) Infection in Anopheline and Culicine Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in the Northeastern United States, 1997–2012. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 14. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2014.1669

Berry RL, Parsons MA, Lalonde-Weigert BJ, Lebio J, Stegmiller H, Bear GT. 1986. Aedes canadensis, a vector of La Crosse virus (California serogroup) in Ohio. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 2: 73–78. https://vectorbio.rutgers.edu/outreach/pubs/Berry1986AeCanadensisVectorLaCrosse.pdf

Bickley WE, Lawrence RS, Ward GM, Shillinger RB. 1977. Dog-to-dog transmission of heartworm by Aedes canadensis. Mosquito News 37: 137–138. https://ia800505.us.archive.org/19/items/cbarchive_117001_dogtodogtransmissionofheartwor1977/MN_V37_N1_P137-138_text.pdf

Carpenter SJ, LaCasse WJ. 1955. Mosquitoes of North America. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Pages 161–163. ISBN: 9780520325081.

Carson PK, Holloway K, Dimitrova K, Rogers L, Chaulk AC, Lang AS, Whitney HG, Drebot MA, Chapman TW. 2017. The Seasonal Timing of Snowshoe Hare Virus Transmission on the Island of Newfoundland, Canada. Journal of Medical Entomology 54: 712–718. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjw219

Cloutier CA, Fyles JW, Buddle CM. 2021. Diversity and community structure of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in suburban, field, and forest habitats in Montréal, Québec, Canada. The Canadian Entomologist 153: 393–411. https://doi.org/10.4039/tce.2021.8

Crans WJ. 2004. A classification system for mosquito life cycles: life cycle types for mosquitoes of the northeastern United States. Journal of Vector Ecology 29: 1–10. https://vectorbio.rutgers.edu/publications/A_classification_system_for_mosq_life_cycles.pdf

Crans WJ. 2015. Aedes canadensis canadensis (Theobald). Rutgers: New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station Center for Vector Biology. https://vectorbio.rutgers.edu/outreach/species/sp21.htm Accessed 2 May 2025.

Crans WJ, Rockel EG. 1968. The Mosquitoes Attracted to Turtles. Mosquito News 28: 332–337. https://vectorbio.rutgers.edu/outreach/pubs/Crans1968MosquitoesAttractedTurtles.pdf

Coleman KJ, Chauhan L, Piquet AL, Tyler KL, Pastula DM. 2021. An Overview of Jamestown Canyon Virus Disease. The Neurohospitalist 11: 277–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/19418744211005948

Darsie RF. 2005. Key to the pupae of the mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) of Florida. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 107: 892–902. https://ia601505.us.archive.org/8/items/biostor-55184/biostor-55184.pdf

Darsie RF, Ward RA. 2005. Identification and Distribution of the Mosquitoes of North America, North of Mexico. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press. Pages 39 and 158. ISBN: 9780813062334.

Freitas LFD, Bartholomay LC. 2021. The Taxonomic History of Ochlerotatus Lynch Arribálzaga, 1891 (Diptera: Culicidae). Insects 12: 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects12050452

Giordano BV, Turner KW, Hunter FF. 2018. Geospatial Analysis and Seasonal Distribution of West Nile Virus Vectors (Diptera: Culicidae) in Southern Ontario, Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15: 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15040614

Harbach RE, Wilkerson RC. 2023. The insupportable validity of mosquito subspecies (Diptera: Culicidae) and their exclusion from culicid classification. Zootaxa 5303: 1–184. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.5303.1.1

Harris MC, Yang F, Jackson DM, Dotseth EJ, Paulson SL, Hawley DM. 2015. La Crosse Virus Field Detection and Vector Competence of Culex Mosquitoes. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 93: 461–467. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.14-0128

Harrison BA, Byrd BD, Sither CB, Whitt PB. 2016. The Mosquitoes of the Mid-Atlantic Region: An Identification Guide. Madison Heights, MI: Publishing XPress. https://gamosquito.org/resources/MidAtlanticIDGuide2016.pdf

Irby WS, Apperson CS. 1988. Hosts of Mosquitoes in the Coastal Plain of North Carolina. Journal of Medical Entomology 25: 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/25.2.85

Jenkins DW, Knight KL. 1952. Ecological Survey of the Mosquitoes of Southern James Bay. The American Midland Naturalist 47: 456–468. https://doi.org/10.2307/2422273

Kalpage KS, Brust RA. 1968. Mosquitoes of Manitoba. I. Descriptions and a Key to Aedes Eggs (Diptera: Culicidae). Canadian Journal of Zoology 46: 699–718. https://doi.org/10.1139/z68-098

Kaura T, Walter NS, Kaur U, Sehgal R. 2022. Different Strategies for Mosquito Control: Challenges and Alternatives. Mosquito Research—Recent Advances in Pathogen Interactions, Immunity, and Vector Control Strategies. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.104594

Magnarelli LA. 1977. Seasonal Occurrence and Parity of Aedes canadensis (Diptera: Culicidae) in New York State, U.S.A. Journal of Medical Entomology 13: 741–745. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/13.6.741

Mallack J, Smith LW, Berry RA, Bickley WE. 1964. Hatching of eggs of three species of Aedine mosquitoes in response to temperature and flooding. Bulletin of the Maryland Agricultural Experiment Station.

Martínez-Mercado JP, Sierra-Santoyo A, Verdín-Betancourt FA, Rojas-García AE, Quintanilla-Vega B. 2022. Temephos, an organophosphate larvicide for residential use: a review of its toxicity. Critical Reviews in Toxicology 52: 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408444.2022.2065967

McCarry MJ. 1996. Efficiency of Altosid® (s-methoprene) liquid larvicide formulated on Biodac® (granular carrier) against spring Aedes species in flooded woodlots. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 12: 497–498. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/content/part/JAMCA/JAMCA_V12_N3_P497-498.pdf

McLean DM, Bergman SKA, Graham EA, Greenfield GP, Olden JA, Patterson RD. 1974. California Encephalitis Virus Prevalence in Yukon Mosquitoes During 1973. Canadian Journal of Public Health 65: 23–28. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41987223

Molaei G, Andreadis TG, Armstrong PM, Diuk-Wasser M. 2008. Host-Feeding Patterns of Potential Mosquito Vectors in Connecticut, USA: Molecular Analysis of Bloodmeals from 23 Species of Aedes, Anopheles, Culex, Coquillettidia, Psorophora, and Uranotaenia. Journal of Medical Entomology 45: 1143–1151. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/45.6.1143

Nasci RS, Moore CG, Biggerstaff BJ, Panella NA, Liu HQ, Karabatsos N, Davies BS, Brannon ES. 2000. La Crosse Encephalitis Virus Habitat Associations in Nicholas County, West Virginia. Journal of Medical Entomology 37: 559–570. https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585-37.4.559

New Jersey Department of Health. 2024. Mosquito Control Program Vector Surveillance Submission Guidance: Summer 2024. https://dep.nj.gov/wp-content/uploads/njfw/mosquito-control-program-vector-surveillance-submission-guidance.pdf

Reinert JF. 2000. New classification for the composite genus Aedes (Diptera: Culicidae: Aedini), elevation of subgenus Ochlerotatus to generic rank, reclassification of the other subgenera, and notes on certain subgenera and species. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 16: 175–188. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/content/part/JAMCA/JAMCA_V16_N3_P175-188.pdf

Rey JR, Walton WE, Wolfe RJ, Connelly CR, O’Connell SM, Berg J, Sakolsky-Hoopes GE, Laderman AD. 2012. North American Wetlands and Mosquito Control. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 9: 4537–4605. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9124537

Rings RW, Hill SO. 1948. The Taxonomic Status of Aedes mathesoni. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 50: 41–49. https://mosquito-taxonomic-inventory.myspecies.info/sites/mosquito-taxonomic-inventory.info/files/Rings%20%26%20Hill%201948.pdf

Shahhosseini N, Frederick C, Racine T, Kobinger GP, Wong G. 2021. Modeling host-feeding preference and molecular systematics of mosquitoes in different ecological niches in Canada. Acta Tropica 213: 105734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2020.105734

Sherwood JA, Stehman SV, Howard JJ, Oliver J. 2020. Cases of Eastern equine encephalitis in humans associated with Aedes canadensis, Coquillettidia perturbans and Culiseta melanura mosquitoes with the virus in New York State from 1971 to 2012 by analysis of aggregated published data. Epidemiology & Infection 148. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268820000308

Snyman J, Snyman LP, Buhler KJ, Villeneuve CA, Leighton PA, Jenkins EJ, Kumar A. 2023. California Serogroup Viruses in a Changing Canadian Arctic: A Review. Viruses 15: 1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/v15061242

Theobald FV. 1901. A monograph of the Culicidae of the world, vol. 2, p. viii. London: British Museum Order of Trustees. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/269065#page/14/mode/1up

Trueman DW, McIver SB. 1986. Temporal patterns of host-seeking activity of mosquitoes in Algonquin Park, Ontario. Canadian Journal of Zoology 64: 731–737. https://doi.org/10.1139/z86-108

Vahey GM, Lindsey MP, Staples JE, Hills SL. 2021. La Crosse Virus Disease in the United States, 2003–2019. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 105: 807–812. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.21-0294

Walker ED, Yuill TM. 2023. Snowshoe hare virus: discovery, distribution, vector and host associations, and medical significance. Journal of Medical Entomology 60: 1252–1261. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjad128

Webster D, Dimitrova K, Holloway K, Makowski K, Safronetz D, Drebot M. 2017. California Serogroup Virus Infection Associated with Encephalitis and Cognitive Decline, Canada, 2015. Emerging Infectious Diseases 23: 1423–1424. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2308.170239

Wilkerson RC, Linton YM, Fonseca DM, Schultz TR, Price DC, Strickman DA. 2015. Making Mosquito Taxonomy Useful: A Stable Classification of Tribe Aedini that Balances Utility with Current Knowledge of Evolutionary Relationships. PLoS One 10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0133602

Wills W, Fish DD. 1973. Succession of mosquito species in a woodland snowpool in Pennsylvania. Proceedings, New Jersey Mosquito Extermination Association 60: 129–134.

Wilmot TR, Allen DW, Harkanson BA. 1993. Field trial of two Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis formulations for control of Aedes species mosquitoes in Michigan woodlands. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 9: 344–345. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/content/part/JAMCA/JAMCA_V09_N3_P344-345.pdf

Yamany AS, Adham FK, Abdel-Gaber R. 2024. Morphological description of the pupa of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) using a scanning electron microscope. Arquivo Brasileiro de Medicina Veterinária e Zootecnia 76: 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-4162-13120