The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

Anopheles is a genus of mosquito species commonly known as marsh mosquitoes. The genus consists of around 500 species, with only a small portion of them capable of transmitting human malaria parasites belonging to the genus Plasmodium (Trent, 2005). With the global concerted efforts to eliminate malaria, some regions and countries are in or approaching the elimination phase (Hemingway et al., 2016). However, residual malaria transmission lingers in malaria pre-elimination zones that may be vectored by lesser-known Anopheles species. One such species may be Anopheles squamosus, which is one of the most abundantly caught anopheline species in malaria vector surveillance studies in southern African countries like Zambia (Stevenson 2016a; Nguyen et al., 2025). Though An. squamosus is predominantly recognized as a species that feeds on animals other than humans, it has been documented to take blood from human hosts, particularly in southern Zambia (Gebhardt et al., 2022). Additionally, Plasmodium falciparum, a causal agent of human malaria, was detected in An. squamosus (Stevenson et al., 2016b; Gebhardt et al., 2022). These factors position An. squamosus as an important vector of malaria in some pre-elimination zones.

Synonymy

Anopheles squamosus Theobald 1901 (Theobald, 1907)

Anopheles arnoldi Stephens & Christophers (Stephens & Christophers, 1908)

Anopheles pretoriensis Gough (Gough, 1910)

Anopheles tanarivivensis Verntrillon (Verntrillon, 1906)

Distribution

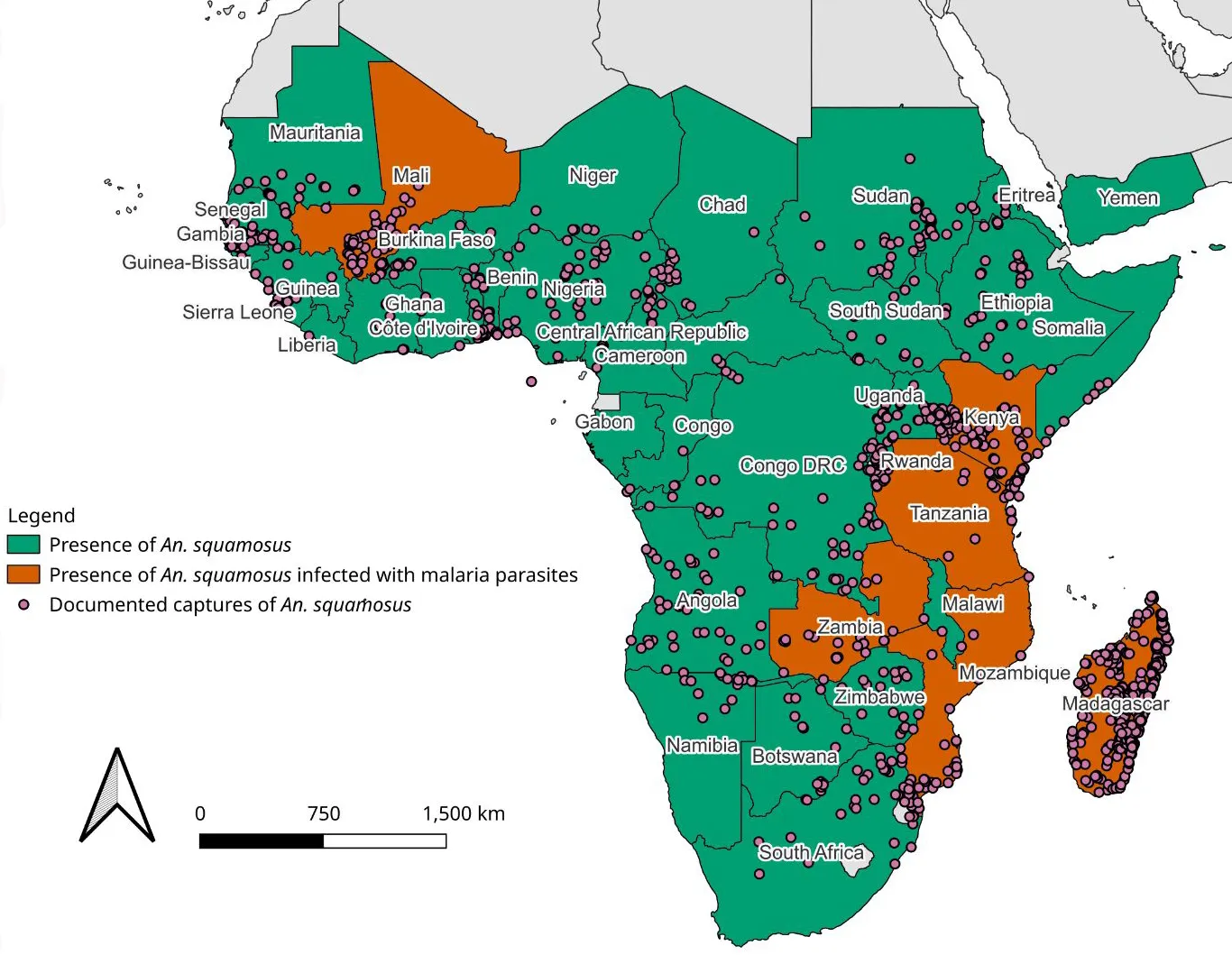

Anopheles squamosus is predominantly found across sub-Saharan Africa, including Madagascar, as shown in Figure 1 (Nguyen et al., 2025). The species has been implicated in malaria transmission because this species has tested positive for the malaria parasite belonging to the Plasmodium genus in Madagascar, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and Zambia. Figure 1, a map of the African continent and part of the Arabian Peninsula, shows the distribution of An. squamosus mosquitoes over most of Africa and in Yemen. Malaria-infected An. squamosus mosquitoes have been found in Mali, Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Mozambique, and Madagascar. According to the map, An. Squamosus is not present in Western Sahara, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, or Djibouti. Confirmed captures are scattered across Africa. (Figure 1) (Finney et al., 2021).

Credit: Map generated using QGIS program—QGIS.org. (2025). QGIS Geographic Information System. QGIS Association. https://www.qgis.org

Description

Adults

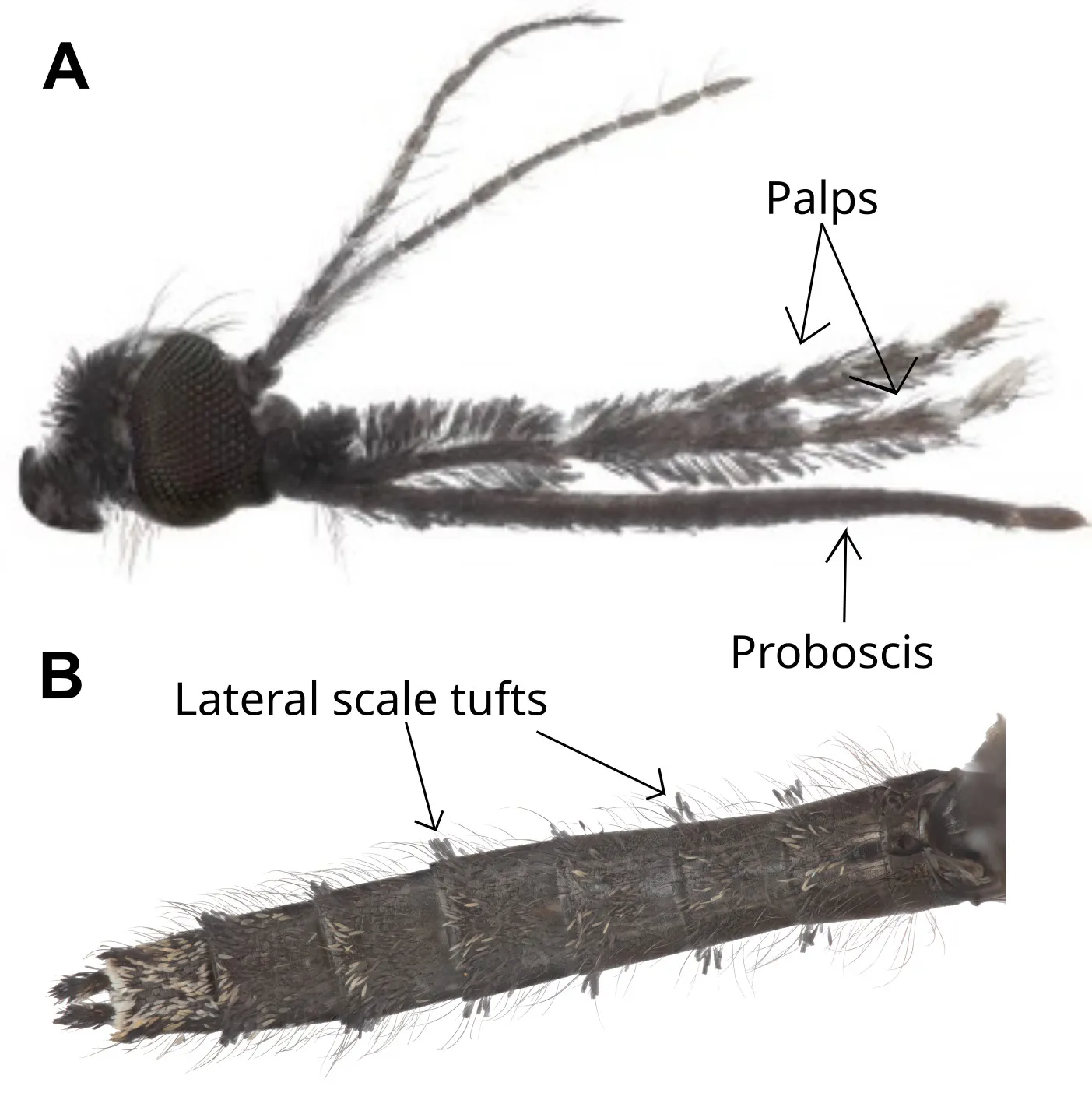

One of the most distinguishing features of female Anopheles mosquitoes compared to other mosquito genera is that their palps (sensory mouthparts) are as long as their proboscises (feeding mouth parts) (Figure 2). Female Anopheles are distinguished by having an evenly rounded scutellum (top part of thorax), and dark brown or black scales. They rest with their abdomens sitting upright, compared to other mosquito genera that sit with their abdomens sitting parallel to the surface (Foster & Walker, 2019). Anopheles squamosus are identifiable to species via their shaggy palps and large lateral scale tufts on their abdomen (Figure 2). In the adult stage, An. squamosus is indistinguishable from An. cydippis based on adult characteristics.

Credit: L. Reeves and V. Nguyen

Eggs

Anopheline mosquitoes lay clutches of 50 to 200 individual eggs that are 0.5 mm x 0.2 mm (0.197 inches x .008 inches) in size. They have specialized floats that will allow them to remain on the surface of the water.

Larvae

Anopheline larvae emerge from eggs after 2–3 days and feed on bacteria and microorganisms in the water. In southern Zambia, An. squamosus larvae can be found in well water, rainwater collected in roadside pools, pastures, and irrigation ditches. They rest and position themselves parallel to the water’s surface and breathe air through abdominal openings called spiracles. Anopheline larvae will go through four larval instars before pupation.

Pupae

The genus Anopheles has distinct, comma-shaped pupae. Their heads and thoraxes are fused into cephalothoraxes (Figure 3). The pupae must sit at the surface of the water and breathe through specialized respiratory apparatuses located on their cephalothoraxes (Figure 3). They do not feed during this life stage; however, they can move rapidly to avoid predation.

Credit: J. Harmsky, used with permission

Life Cycle and Biology

Anopheles species undergo complete metamorphosis in which they complete their first three life stages (egg, larva, and pupa) in bodies of water. Eggs are laid individually in bodies of water, and the emerging larvae will undergo four larval instars before pupation. It takes an anopheline egg 10–14 days on average to become an adult, depending upon the temperature. Adults will quickly mate after pupating.

As adults, male and female Anopheles species feed on sugar sources. Females require a blood meal for egg production (Barredo & DeGennaro, 2020). Anopheles squamosus typically feed on livestock such as cattle or goats. However, several studies confirmed several blood meals belonging to humans from An. squamosus collected in Zambia and Madagascar (Nguyen et al., 2025).

Anopheline communities are also impacted by environmental factors, such as shifts in temperature and rainfall throughout the season and years (Cross et al., 2021). Human activities can create changes for Anopheles species, including behaviorally targeted control methods like long-lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLIN) and indoor residual spray (IRS) campaigns (Mwema et al., 2022). There is little data on the seasonal or interannual changes in An. squamosus to date. This could be relevant in future research of the species to observe changes in environmental range expansion.

Medical Significance

Plasmodium falciparum is the causal agent of the deadliest form of human malaria. In 2023, there were 597,000 deaths caused by malaria globally (WHO, 2024). Malaria in humans can range from being asymptomatic to causing fever, nausea, anemia, and jaundice (WHO, 2024). Given the increasing evidence of An. squamosus playing a role in malaria transmission in pre-elimination areas, it remains critical to continue to expand our knowledge of the biology of An. squamosus (Nguyen et al., 2025).

While An. squamosus is a concern for malaria transmission, it also poses a threat for Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV). Rift Valley fever virus can cause critical disease in animals, but severe symptoms in humans are rare (Hartman, 2017; CDC, 2024). While Aedes mosquitoes are known to be the main vector of RVFV, Anopheles and Culex mosquitoes are secondary vectors (Seufi & Galal, 2010). In Madagascar, RVFV was detected in multiple pools of An. squamosus larvae, suggesting that this species could potentially be a vector of RVFV (Ratovonjato et al., 2011).

Management

There are no targeted management strategies developed for An. squamosus yet. Extensive efforts have been made towards malaria eradication, particularly the elimination of primary vectors of malaria biting humans indoors and resting indoors. These techniques include comprehensive indoor residual spraying (IRS) campaigns, and mass distribution of insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs) (Moonasar et al., 2012). Though An. squamosus can be found in indoor settings that are easily treated by IRS and ITNs, populations also exhibit outdoor feeding behavior depending upon the location they are inhabiting (Nguyen et al., 2025). This can circumvent current methods of malaria control and contribute to residual transmission of these parasites. Understanding the biology and behavior of An. squamosus in different regions is needed to develop a more targeted control effort for this species.

References

Barredo, E., & DeGennaro, M. (2020). Not just from blood: Mosquito nutrient acquisition from nectar sources. Trends in Parasitology, 36(5), 473–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2020.02.003

CDC. (2024, June 24). About Rift Valley fever (RVF). Rift Valley Fever. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/rvf/index.html

Cross, D. E., Thomas, C., McKeown, N., Siaziyu, V., Healey, A., Willis, T., Singini, D., Liywalii, F., Silumesii, A., Sakala, J., Smith, M., Macklin, M., Hardy, A. J., & Shaw, P. W. (2021). Geographically extensive larval surveys reveal an unexpected scarcity of primary vector mosquitoes in a region of persistent malaria transmission in western Zambia. Parasites & Vectors, 14(1), 91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04540-1

Finney, M., McKenzie, B. A., Rabaovola, B., Sutcliffe, A., Dotson, E., & Zohdy, S. (2021). Widespread zoophagy and detection of Plasmodium spp. in Anopheles mosquitoes in southeastern Madagascar. Malaria Journal, 20(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-020-03539-4

Foster, W. A., & Walker, E. D. (2019). Mosquitoes (Culicidae). In Medical and Veterinary Entomology (pp. 261–325). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-814043-7.00015-7

Gebhardt, M. E., Searle, K. M., Kobayashi, T., Shields, T. M., Hamapumbu, H., Simubali, L., Mudenda, T., Thuma, P. E., Stevenson, J. C., Moss, W. J., Norris, D. E., & Southern and Central Africa International Center of Excellence for Malaria Research. (2022). Understudied anophelines contribute to malaria transmission in a low-transmission setting in the Choma District, Southern Province, Zambia. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 106(5), 1406–1413. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.21-0989

Hartman, A. (2017). Rift Valley fever. Clinics in Laboratory Medicine, 37(2), 285–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cll.2017.01.004

Hemingway, J., Shretta, R., Wells, T. N. C., Bell, D., Djimdé, A. A., Achee, N., & Qi, G. (2016). Tools and strategies for malaria control and elimination: What do we need to achieve a grand convergence in malaria? PLoS Biology, 14(3), e1002380. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002380

Moonasar, D., Nuthulaganti, T., Kruger, P. S., Mabuza, A., Rasiswi, E. S., Benson, F. G., & Maharaj, R. (2012). Malaria control in South Africa 2000–2010: Beyond MDG6. Malaria Journal, 11(1), 294. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-11-294

Mwema, T., Lukubwe, O., Joseph, R., Maliti, D., Iitula, I., Katokele, S., Uusiku, P., Walusimbi, D., Ogoma, S. B., Tambo, M., Gueye, C. S., Williams, Y. A., Vajda, E., Tatarsky, A., Eiseb, S. J., Mumbengegwi, D. R., & Lobo, N. F. (2022). Human and vector behaviors determine exposure to Anopheles in Namibia. Parasites & Vectors, 15(1), 436. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-022-05563-6

Nguyen, V. T., Dryden, D. S., Broder, B. A., Tadimari, A., Tanachaiwiwat, P., Mathias, D. K., Thongsripong, P., Reeves, L. E., Ali, R. L. M. N., Gebhardt, M. E., Saili, K., Simubali, L., Simulundu, E., Norris, D. E., & Lee, Y. (2025). A comprehensive review: Biology of Anopheles squamosus, an understudied malaria vector in Africa. Insects, 16(2), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16020110

QGIS.org. (2025). QGIS Geographic Information System. QGIS Association. https://www.qgis.org

Ratovonjato, J., Olive, M.-M., Tantely, L. M., Andrianaivolambo, L., Tata, E., Razainirina, J., Jeanmaire, E., Reynes, J.-M., & Elissa, N. (2011). Detection, isolation, and genetic characterization of Rift Valley fever virus from Anopheles (Anopheles) coustani, Anopheles (Anopheles) squamosus, and Culex (Culex) antennatus of the Haute Matsiatra region, Madagascar. Vector Borne and Zoonotic Diseases (Larchmont, N.Y.), 11(6), 753–759. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2010.0031

Seufi, A. M., & Galal, F. H. (2010). Role of Culex and Anopheles mosquito species as potential vectors of Rift Valley fever virus in Sudan outbreak, 2007. BMC Infectious Diseases, 10(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-10-65

Stevenson, J. C., Pinchoff, J., Muleba, M., Lupiya, J., Chilusu, H., Mwelwa, I., Mbewe, D., Simubali, L., Jones, C. M., Chaponda, M., Coetzee, M., Mulenga, M., Pringle, J. C., Shields, T., Curriero, F. C., Norris, D. E., & Southern Africa International Centers of Excellence in Malaria Research. (2016a). Spatio-temporal heterogeneity of malaria vectors in northern Zambia: implications for vector control. Parasites & Vectors, 9(1), 510. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1786-9

Stevenson, J. C., Simubali, L., Mbambara, S., Musonda, M., Mweetwa, S., Mudenda, T., Pringle, J. C., Jones, C. M., & Norris, D. E. (2016b). Detection of Plasmodium falciparum Infection in Anopheles squamosus (Diptera: Culicidae) in an Area Targeted for Malaria Elimination, Southern Zambia. Journal of Medical Entomology, 53(6), 1482–1487. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjw091

Trent, R. J. (2005). Infectious diseases. In Molecular Medicine (pp. 193–220). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012699057-7/50008-4

World Health Organization (WHO). (2024). World Malaria Report 2024. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240104440