The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

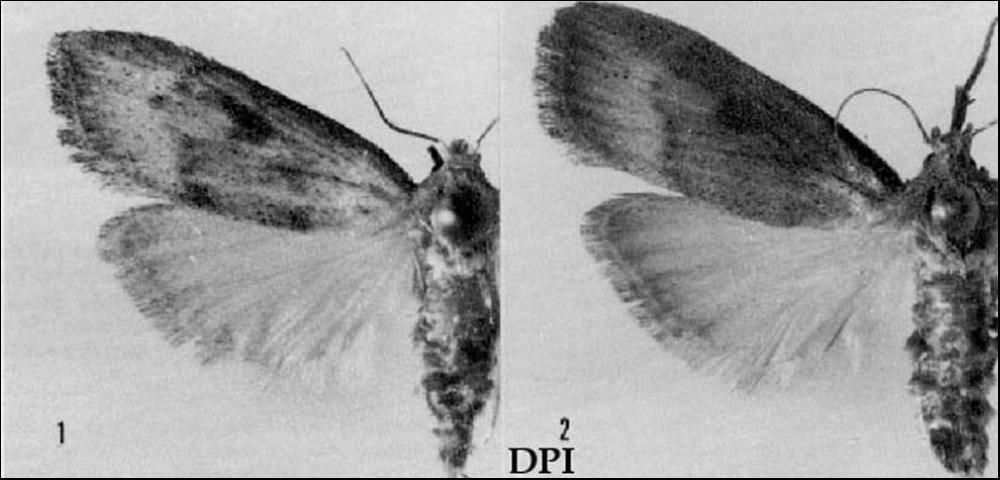

The bromeliad pod borer, Epimorius testaceellus (Figure 1), was described by Ragonot (1887) from a specimen collected in Jamaica. In 1974, the senior author (Heppner) reared it from flower pods of the bromeliad Tillandsia fasciculata in Florida. Subsequently, it was identified and reported on by Ferguson (1991). Larvae of this pyralid moth do considerable damage to the flower pods of infested T. fasciculata, although populations appear to be localized and uncommon.

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Distribution

The bromeliad pod borer occurs over much the same distribution as its host plant: subtropical Florida and south into the West Indies and South America (Ferguson 1991; Whalley 1964). The senior author (Heppner) reared the moth from larvae from Palmdale, Glades County, in May 1974 and May 1975; from Miami, Miami-Dade County, in January 1974; and from near Lake Placid, Highlands County, in May 1975. Other records come from Broward County, seen in the months of March and July, and from Miami-Dade County in March.

Description and Diagnosis

Adults of E. testaceellus are brown with highlights of tan shades on the forewings; hindwings are light tan. Males have slight amounts of red-brown scales on the forewing in fresh specimens. Wingspread ranges from 20 mm in males to 26 mm in females. Larvae are yellow, with amber head capsules.

Larvae of six other small moths have been reported from T. fasciculata in Florida. They are Pyralis farinalis (L.), Opogona sacchari (Bojer) (known as banana moth), Xylesthia pruniramiella Clemens, Pyroderces sp., Bleptina sp., and an unidentified species of the family Tortricidae. They all differ in feeding habits from E. testaceellus (Table 1).

Host Plants

Thus far, the only confirmed host plant of Epimorius testaceellus is the bromeliad Tillandsia fasciculata Swartz. A localized outbreak of the moth could cause extensive damage (Figure 2). However, the moth has a parasitoid (see Natural Enemies below) that may prevent outbreaks. The adult moth does not appear to be responsive to light traps, because few if any specimens have been collected in Florida other than by rearing from larvae collected from Tillandsia fasciculata.

Larvae of a pyralid moth caused damage to leafbases of Tillandsia variabilis Schlechtendal (known earlier as Tillandsia valenzuelana A. Richard) at Copeland, Collier County, in January 1976. Whatever this species was, it almost certainly was not Epimorius testaceellus.

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Natural Enemies

Larvae of a wasp are reported as parasitoids of Epimorius testaceellus larvae in Florida. Orange-colored adult wasps were reared by the senior author (Heppner) from pod borer larvae collected from Glades and Miami-Dade counties, and were named and described by Bugbee (1975, 1976) as Eurytoma aerflora Bugbee (Hymenoptera: Eurytomidae). This wasp may be widespread (because it was collected in Miami-Dade and Glades counties), and it may prevent outbreaks of the moth, but nothing else is known about it.

Behavior

Tillandsia fasciculata is strictly epiphytic (Langdon 1981) and grows on rough-barked trees, especially cypress (Taxodium). It has three varieties (var. fasciculata, var. densispica, and var. clavispica) in Florida (Wunderlin 1998). Each plant produces only one flower spike and dies thereafter. Although flowering plants of this species may be found in any month of the year in Florida, the peak of the flowering season is March through May. Old flowers may hang on plants for many weeks, but the timing of flowering seems largely to be aimed at release of seeds at the onset of a rainy period, especially the summer rainy period of July through August. The pod borer excavates flower pods (not seed capsules) of Tillandsia fasciculata. Larval damage is evidenced by frass ejected from the flower capsule (pod) and discoloration of the flowers. Each larva seems to consume several flower pods.

Pupation occurs within the shell of the excavated flower pod, usually toward the apex of an inflorescence. A silken cocoon is spun against the flower-capsule walls and an exit hole is partially chewed in an exterior wall near the pod base, leaving the adult to push a thin plant flap upon emergence. The head of the pupa is placed just beneath the exit hole of the flower capsule. Pupation lasts about 17 days during the winter and six to 14 days in May. Adults emerge in early evening. Adults are known thus far from January through February and May. Additional study is likely to show that they occur in all months of the year, but that most occur in March through May, coinciding with the peak flowering period of the host plant.

Selected References

Bugbee RE. 1975. A new species of the genus Eurytoma (Hymenoptera: Eurytomidae) from a pyralid occurring in the flower pods of Tillandsia fasciculata. Journal of the Georgia Entomological Society 10: 91-93.

Bugbee RE. 1976. Description of the male of Eurytoma aerflora Bugbee (Hym.: Eurytomidae). Journal of the Georgia Entomological Society 11: 181-182.

Ferguson DC. 1991. Review of the genus Epimorius Zeller and first report of the occurrence of E. testaceellus Ragonot in the United States (Pyralidae: Galleriinae). Journal of the Lepidoptera Society 45: 117-123.

Frank JH. (1999). Bromeliad biota. http://entomology.ifas.ufl.edu/frank/bromeliadbiota/ (14 October 2010)

Langdon KR. 1981. The native Florida bromeliad or wild-pine, Tillandsia fasciculata. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry Botany Circular 15: 1-2.

Ragonot EL. 1887. Diagnoses of North American Phycitidae and Galleriinae. Paris. [privately publ.]

Whalley PES. 1964. Catalogue of the Galleriinae (Lepidoptera, Pyralidae) with descriptions of new genera and species. Acta Zool. Cracoviensia 9: 561-618.

Wunderlin RP, Hansen B. 2003. Guide to the Vascular Plants of Florida. University of Florida Press. 796 pp.