The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

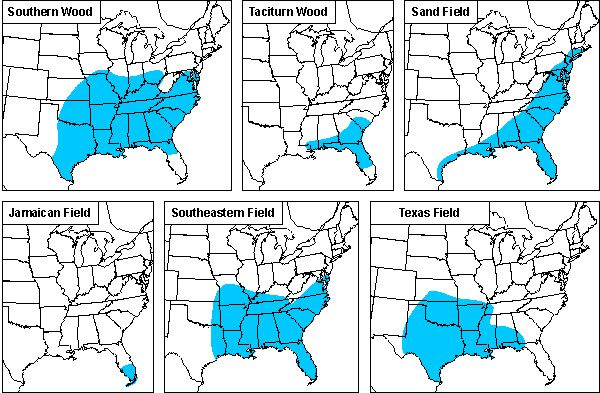

Field crickets are large (15 to 31 mm), dark, and usually found on the ground. Florida has six species, four of which are characteristic of fields and other open areas. The other two live in wooded habitats.

Species of field crickets look pretty much alike, and until 1957 all United States species were (wrongly) thought to belong to a single species. Only when biologists started studying the songs of field crickets were they able to separate the species. Calling songs are revealing because they are an important means for the field crickets themselves to recognize members of their own species: Male crickets use species-characteristic calling songs to attract sexually responsive females. Females are attracted to the calling songs of males of their own species and not to songs of other species. Once biologists had distinguished species of field crickets by their songs, they discovered that the species also differed in morphology, life cycles, and geographic and ecological distributions.

Because of their songs and convenient size and because they are easily reared, field crickets are favorite subjects for studies of behavior, acoustic communication, and neurophysiology.

Distribution

Two of our six species occur throughout the state; two are widespread but missing from south peninsular Florida; one occurs only there. The remaining species occurs only in panhandle Florida.

Identification

After you determine what species occur in your area, go to the accounts of candidate species to learn their distinguishing characteristics:

Gryllus assimilis, Jamaican field cricket

Gryllus firmus, sand field cricket

Gryllus fultoni, southern wood cricket

Gryllus ovisopis, taciturn wood cricket

Gryllus rubens, southeastern field cricket

Gryllus texensis, Texas field cricket

Song

Except for the taciturn wood cricket, males of Florida field crickets can be identified by their distinctive calling songs, as seen in pictures of the songs and as can be heard in the wav files that are linked to the spectrograms and to the accounts of the species. To produce a song, the male raises its forewings above its abdomen to an angle of ca. 45°F and opens and closes them in a species-specific rhythm. On each closing stroke, the scraper (a sharp edge near the wing base) of one wing engages the file (a vein with many evenly spaced small teeth beneath) of the other wing, causing the wing membranes to vibrate and produce a pulse of sound. The opening strokes are silent. Thus field cricket calling songs consist of some pattern of sound pulses that correspond to forewing closures. Two of our species produces long runs of pulses, termed trills, whereas the others produce briefer groupings, termed chirps.

Only males have the forewings specialized for sound making. Females are mute. In addition to the calling song (produced by solitary males), males produce loud fight songs when they encounter other males and softer-sounding courtship songs when they encounter females.

To produce a song, the male raises its fore wings above its abdomen to an angle of ca. 45° and opens and closes them in a species-specific rhythm. On each closing stroke, the scraper (a sharp edge near the wing base) of one wing engages the file (a vein with many evenly spaced small teeth beneath) of the other wing, causing the wing membranes to vibrate and produce a pulse of sound.

In this animated gif, the male is rubbing his wings three times and then pausing, three times and pausing, etc.

The song produced would be a three-pulsed chirp. If this cricket's wing movements were much faster, but maintained the same pattern, its chirps would be similar to those of the southern wood cricket. Here is the slowed song (171 Kb wav file) of that species. [If you listen to the slowed song, you may have to reload this page to re-activate the gif.]

Note: The cricket in the gif is atypical in two respects: In crickets the right wing is usually above the left wing during calling (making the file beneath the right wing the functional one), and during calling the wings do not separate near the tips as in the animation.

Wing Dimorphism

Adult field crickets may be short-winged (=micropterous; the hindwings completely concealed by the forewings), or long-winged (=macropterous; the hind wings protruding from beneath the fore wings to form "tails"). Three of our species are dimorphic (both forms occur), one is wholly long-winged, and two are always short-winged. Only long-winged individuals can fly, and the four species in which some or all individual are long-winged are characteristic of ecologically transient habitats (i.e., fields as opposed to woods).

Economic Importance

Field crickets seldom cause problems in Florida. Occasionally they become abundant in suburbs and cause distress by getting into garages or coming to lights in nuisance numbers. Being omnivores, they sometimes do harm by eating seedling plants and sometimes do good by eating fly pupae. Some people enjoy the songs, most never hear them, and a few are bothered by them. Field crickets sometimes chew holes in fabric, not for nutrition (unless the fabric is soiled with food) but to "get to the other side."

Selected References

Alexander RD. 1957. The taxonomy of the field crickets of the eastern United States (Orthoptera: Gryllidae: Acheta). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 50: 584–602.

Alexander RD. 1968. Life cycle origins, speciation, and related phenomena in crickets. Quarterly Review of Biology 43: 1–41.

Giordano R, Jackson JJ, Robertson HM. 1997. The role of Wolbachia bacteria in reproductive incompatibilities and hybrid zones of Diabrotica beetles and Gryllus crickets. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA. 94: 11439–11444.

Harrison RG, Bogdanowicz SM. 1995. Mitochondrial DNA phylogeny of North American field crickets: Perspectives on the evolution of life cycles, songs, and habitat associations. Journal of Environmental Biology 8: 209–232.

Nickle DA, Walker TJ. 1974. A morphological key to field crickets of southeastern United States (Orthoptera: Gryllidae: Gryllus). Florida Entomologist 57: 8–12.

Huber F, Moore TE, Loher W, eds. 1989. Cricket Behavior and Neurobiology. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY. 565 pp.

Walker TJ. 1986. Monitoring the flights of field crickets (Gryllus spp. ) and a tachinid fly (Euphasiopteryx ochracea) in north Florida. Florida Entomologist 69: 678–685.

Walker TJ. 1993. Phonotaxis in female Ormia ochracea (Diptera: Tachinidae), a parasitoid of field crickets. Journal of Insect Behavior 6: 389–410.

Walker TJ. (2011). Genus Gryllus, field crickets. Singing Insects of North America. (25 February 2022).

Walker TJ, Sivinski JM. 1986. Wing dimorphism in field crickets (Orthoptera: Gryllidae: Gryllus). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 79: 84–90.

Wineriter SA, Walker TJ. 1988. Group and individual rearing of field crickets (Orthoptera: Gryllidae). Entomological News 99: 53–62.