The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

True potato beetles are members of the genus Leptinotarsa, with more than 40 species throughout North and South America including at least 10 species found north of Mexico. While most species north of Mexico are found in the southwestern United States, two species are found either in the eastern states or throughout most of the United States (Arnett 2002). The more notable of these two is the Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say), which is a serious pest of potatoes and other solanaceous plants.

Credit: David Cappaert, Michigan State University, www.insectimages.org

The Colorado potato beetle was first discovered by Thomas Nuttal in 1811 and described in 1824 by Thomas Say from specimens collected in the Rocky Mountains on buffalo-bur, Solanum rostratum Ramur. The insect's association with the potato plant, Solanum tuberosum (L.), was not known until about 1859 when it began destroying potato crops about 100 miles west of Omaha, Nebraska. The insect began its rapid spread eastward, reaching the Atlantic Coast by 1874.

The evolution of the name Colorado potato beetle is curious because the beetle is believed to have originated in central Mexico, not Colorado. It had a series of names from 1863 to 1867, including the ten-striped spearman, ten-lined potato beetle, potato-bug, and new potato bug. Colorado was not associated with the insect until Walsh (1865) stated that two of his colleagues had seen large numbers of the insect in the territory of Colorado feeding on buffalo-bur. This convinced him that it was native to Colorado. It was Riley (1867) who first used the combination Colorado potato beetle.

Distribution

The Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say), occurs in Mexico and in most of the United States (except Alaska, California, Hawaii, and Nevada), including Florida. It was first reported in Florida in 1920, but it is not often a major pest. It also occurs in southern Canada and is a pest in Central America. The species has been introduced into Europe and parts of Asia (Capinera 2001).

The false potato beetle, Leptinotarsa juncta (Germar), is found primarily in the eastern United States from northern Florida to eastern Texas (with only Sabine County reported as of 2005) (Quinn 2008), north to Missouri, southern Illinois and Indiana, and east to Maryland, West Virginia, and Virginia.

Description

The genus Leptinotarsa is assigned to the tribe Doryphorini containing three genera in the United States, recognized by having the procoxal cavities open behind, simple claws separate at the base and usually divergent. Species of Leptinotarsa are recognized by the following features: maxillary palpi (mouthparts) with apical segment shorter than preceding, truncate; mesosternum not raised above the level of prosternum; profemur of male simple.

Two species of Leptinotarsa occur in Florida: Leptinotarsa decemlineata, the Colorado potato beetle, and Leptinotarsa juncta (Germar), the false potato beetle. The latter incorrectly has been called the "false Colorado potato beetle" because of its similarity to Leptinotarsa decemlineata.

Adults

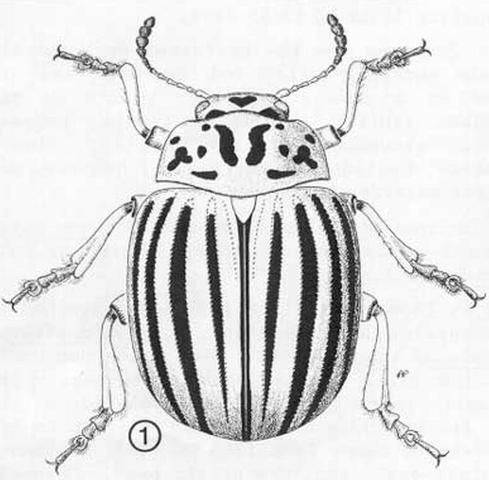

The adults measure about 3/8 inch long and are yellowish orange with five black stripes per elytron (Wilkerson et al. 2005). They are robust and oval in shape when viewed from above. The head has a triangular black spot, and the thorax has irregular dark markings (Capinera 2001).

In Leptinotarsa decemlineata, the pale-yellow elytra are outlined in black, with each elytron having five vittae (broad longitudinal stripes). Vitta 1 is shorter than the other four and adjacent to the sutural margin. Vittae 2 through 5 extend more than half the length of the elytron and are very distinct. Elytron punctation is coarse in irregular rows. The underside of the beetle and the legs are mostly dark (Capinera 2001).

Credit: Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University, www.insectimages.org

Credit: David Cappaert, Michigan State University, www.insectimages.org

In Leptinotarsa juncta, each pale-yellow elytron has five black vittae (broad longitudinal stripes), with vitta 1 bordering sutural margin and extending from just below the base to the apex. Vitta 2 is shorter than the first, not reaching the base. Vitta 3 and 4 connect at the apex of the elytron with space between black. Vitta 5 is along the lateral margin of the elytron. Punctation is coarse, in very regular rows outlining each vitta. There is a distinct black spot on the outer margin of the femur. The legs are mostly orangish in color.

Credit: David Cappaert, Michigan State University, www.insectimages.org

Eggs

The eggs are bright orange and football-shaped, about 1.7–1.8 mm (1/16 in) long and 0.8 mm (< 1/16 in) wide. Females use a yellowish adhesive to deposit eggs on the lower surface of the foliage in clusters of five to 100, but 20 to 60 eggs are more common. The larva becomes visible in the last 12 hours before hatching. Under field conditions, females can lay 200–500 eggs, but this may be an underestimate (Capinera 2001).

The eggs of the false potato beetle are slightly larger, and fewer are found in a cluster.

Credit: James Castner, University of Florida

Larvae

The small, cyphosomatic (dorsal and ventral surfaces distinctly nonparallel), reddish larvae of the Colorado potato beetle are 1/2 inch long when mature. The larvae typically have two rows of black spots down the sides. The larvae are very plump, and the abdomen is strongly convex. Larvae bear a terminal proleg at the tip of the abdomen as well as three pairs of thoracic legs. (Capinera 2001).

Credit: University of Florida

False potato beetle larvae are generally paler (almost white) and have one row of black spots.

Credit: Anita Gould

Pupae

Mature larvae burrow 2–5 cm (~1/8–¼ in) into the soil and after about two days begin to pupate. Colorado potato beetle pupae are oval and orangish in color. The mean development time is about 5.8 days (Capinera 2001).

Credit: Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University, from www.insectimages.org

Life Cycle

The life cycle of the Colorado potato beetle starts with the adult at the overwintering stage and can be as short as 30 days (Capinera 2001). Adults dig into the soil to a depth of several inches and emerge in the spring. They feed on newly sprouted host plants where they mate.

Females deposit eggs on the surface of the host plant's leaves, usually on the undersurface, protected from direct sunlight. Overwintering adults usually feed for five to 10 days before mating and producing eggs (Capinera 2001). Adult females deposit over 300 eggs during a period of four to five weeks. Eggs hatch in four to 10 days depending in part on temperature and humidity (Capinera 2001).

The four larval instars last a total of 21 days. The larvae feed almost continuously on the leaves of the host plant, stopping only when molting.

Larvae drop from the plants and burrow into the soil where they construct a spherical cell and transform into yellowish pupae. This lasts from five to 10 days. There are one to three generations per year, depending on latitude; however, two generations can occur even as far north as Canada. In the south, the third generation usually feeds on weeds and is often overlooked (Capinera 2001).

The life cycle of the false potato beetle is similar to that of the Colorado potato beetle. Eggs hatch in four to five days and the larvae feed on the leaves of the host plants. There are four larval instars lasting 21 days. The larvae drop to the soil to pupate, and pupation lasts 10 to 15 days.

Hosts

Potatoes are the preferred host for the Colorado potato beetle, but it may feed and survive on a number of other plants in the family Solanaceae, including belladonna, common nightshade, eggplant, ground cherry, henbane, horse-nettle, pepper (rarely), tobacco, thorn apple, tomato, and, its first recorded host plant, buffalo-bur. The Colorado potato beetle has displayed an ability to adjust its host range to locally abundant Solanum species. Colorado potato beetles also feed on non-solanaceous plants, but this is rare and these plants should not be considered normal hosts (Capinera 2001).

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS

The false potato beetle is found primarily on the common noxious weed, horse-nettle, Solanum carolinense L. It also feeds on other solanaceous plants, such as species of ground cherry or husk tomato, Physalis spp., and nightshade, Solanum spp.

Key to the Leptinotarsa spp. of Florida

1. Elytral punctation in regular rows from base to apex, vitta 3 and 4 connect at apex of elytron, space between black coloration; black spot on outer margin of the femur. (eastern U.S.)..... Leptinotarsa juncta (Germar)

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

1'. Elytral punctation irregular, not forming regular rows, no black colored space between vitta 3 and 4; no black spot on legs. (widespread).... Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say)

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Management

Sampling

Entire plants should be examined for above-ground life stages. The adults are attracted to the color yellow and can be captured with traps. However, traps are seldom used because the various life stages are so apparent on plants (Capinera 2001).

Cultural Control

The Colorado potato beetle may be managed culturally by crop rotation or destruction of crop debris. Distances of at least 0.5 km (~0.3 miles) are required to provide protection if crops are rotated. Beetles initially disperse by walking, so crop rotation and/or trenching can significantly reduce infestations. Trenches with a 45° or greater slope can capture 50% or more of the beetles (Capinera 2001).

Biological Control

While many natural enemies have been identified, they are usually not able to control Colorado potato beetle populations below the necessary levels. Among these natural enemies are predators such as green lacewings, several predatory stink bugs, and the spined soldier bug. The most important parasitoid is the tachinid fly Myiopharus doryphorae (Riley), which builds to high densities in the autumn, affecting the last generation of beetles. In Colorado, parasitism rates are high early in the season and prevent Leptinotarsa decemlineata from becoming a serious pest (Capinera 2001).

Chemical Control

Insecticides are commonly used to control populations of Colorado potato beetle, but resistance to insecticides develops rapidly (Wilkerson et al. 2005). Some strains of the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis are effective, but it must be applied to the first two instars to be effective (Capinera 2001).

Selected References

Arnett Jr RH, Thomas MC, Skeppey PE, Frank JH. 2002. American Beetles, Vol 2. CRC Press. Boca Raton, USA. 861 pp.

Capinera JL. 2001. Handbook of Vegetable Pests. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Gauthier NL, Hofmaster R, Semel M. 1981. History of Colorado potato beetle control. In Advances in Potato Pest Management. Lashomb JH, Casagrande R (eds). Hutchinson Ross Publishing Company, Stroudsburg, USA.

Hamilton GC, Lashomb JH. 1997. "Effect of insecticides on two predators of the Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae)." Florida Entomologist 80: 10–23. (8 May 2020).

Heiser C. 1969. Nightshades: the Paradoxical Plants. San Francisco, CA: W.H. Freeman and Co.

Jacques Jr RL. 1972. Taxonomic Revision of the Genus Leptinotarsa (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) of North America. Xerox University Microfilms, Ann Arbor, USA. 180 pp.

Pope RD, Madge RB. 1984. "The 'when' and 'why' of the 'Colorado potato beetle'." Bulletin of the Entomological Society of London 8: 175–177.

Quinn M. (December 2008). False potato beetle. Leptinotarsa juncta (Germar): Family Chrysomelidae, Subfamily Chrysomelinae, Tribe Chrysomelini. Texas Beetle Information. http://www.texasento.net/juncta.htm (8 May 2020).

Riley CV. 1867. "The Colorado potato-beetle." Prairie Farmer 20: 389.

Walsh BD. 1865. "The new potato bug, and its natural history." The Practical Entomologist 1: 1–4.