The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

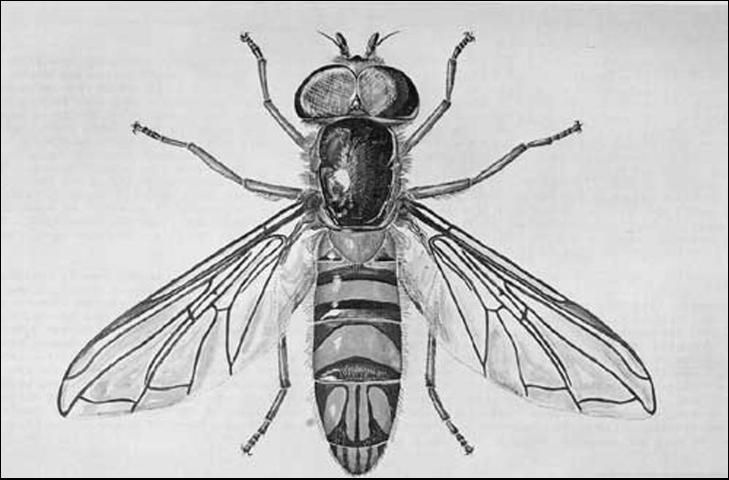

One of the colorful and common little flies in Florida that is most often mistaken for a harmful fruit fly is Allograpta obliqua (Say), a hover fly, flower fly, or syrphid fly. These flies can hover or fly backward, an ability possessed by few insects other than syrphid flies. Adults often visit flowers for nectar or may be seen around aphid colonies where they lay their eggs and feed on honeydew secreted by the aphids. The adults are considered important agents in the cross pollination of some plants. The larvae are important predators, feeding primarily on aphids that attack citrus, subtropical fruit trees, grains, corn, alfalfa, cotton, grapes, lettuce and other vegetables, ornamentals, and many wild plants. When larval populations are high they may reduce aphid populations by 70 to 100%.

Credit: Roy Frye

Synonymy

Scaeva obliqua Say, 1823

Syrphus securiferus Macquart, 1942

Sphaerophoria bacchides Walker, 1849

Syrphus dimensus Walker, 1852

Syrphus signatus Wulp, 1867

Distribution

This hover fly has been found in most of the continental United States from Washington to Maine and into Quebec, Canada, southward to California and Florida; also, Hawaii, Bermuda, Mexico, and parts of the neotropical Americas, including the West Indies.

Identification

The egg is creamy white, sculptured, elongate oval, about 0.84 mm (0.03 in) in length and .25 mm (0.01 in) in diameter. The full-grown larva is 8 to 9 mm (~0.3 in) in length, 2 mm (0.08 in) in width, and about 1.2 mm (0.05 in) in height. Larvae are elongate oval in shape, somewhat flattened on dorsum, with the anterior end drawn out to a point when the insect extends itself. The integument is finely papillose and transversely wrinkled. The fleshy conical elevations are surmounted with pale spines, colored green, with two narrow whitish longitudinal stripes flanking the dorsal vessel.

Larvae of Allograpta obliqua are almost indistinguishable from those of A. exotica (Wiedemann), which occur uncommonly in Florida. The puparium is green; the two whitish larval stripes apparent for a day or two. As the true pupa inside takes on the black and yellow color of the adult, the color of the puparium changes until all of the green disappears. The puparium averages 5.25 mm (0.21 in) long, 2.5 mm (0.1 in) wide, and 2.3 mm (0.1 in) high. Posterior elevation is very gradual. The adult is 6 to 7 mm (~0.2 to 0.3 in) long. This species may be recognized by the generic characters—yellow thoracic stripes and abdominal crossbands; on the fourth and fifth segments, four longitudinal, oblique, yellow stripes or spots; and yellow face lacking a complete median stripe. Eyes of the male are holoptic; those of the female dichoptic.

Credit: James F. Price, University of Florida

Credit: James F. Price, University of Florida

Credit: James F. Price, University of Florida

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Life History and Habits

Adults of Allograpta obliqua occur throughout the year in northern Florida and have been taken in long series in Gainesville in mid-February, but they become much more abundant during spring and summer. In southern Florida they often are abundant even during the winter months. The life cycle varies from as little as three weeks in summer to nine weeks in winter. The eggs are laid singly on the surface of a leaf or twig that bears aphids. They hatch in two to three days during the summer and within eight days in the winter in southern California (Campbell and Davidson 1924).

Wadley (1931) found that the larval stage took five days, with one larva consuming 242 Toxoptera and another 270. Jones (1922) found that larvae took nine days to develop. Miller (1929) reported a larval stage of 10 to 14 days and that the larvae ate an average of 34 aphids per day. Curran (1920) gave the length of the larval stage as 12 to 20 days and recorded one larva as having eaten 265 aphids, an average of 17 per day. The larva fastens itself to a leaf or twig when it is ready to pupate. The pupal stage takes eight to ten days in summer and 18 to 33 days in winter, according to Campbell and Davidson (1924). Wadley (1931) reported a range of six to 11 days with an average of 8.3 days, Miller (1929) six to eight days, Jones (1922) and Curran (1920) five to 17.

Hosts

Many species of aphids have been reported to be hosts of Allograpta obliqua. Species of major economic importance listed by Campbell and Davidson (1924), Curran (1920), Davidson (1916), Heiss (1938), Metcalf (1912, 1916) and Thompson (1928) include Acythosiphon pisum (Harris), Aphis craccivora Koch, Aphis gossyppi Glover, Aphis pomi De Geer, Aphis spiraecola Patch, Brevicoryne brassicae (Linnaeus), Chromaphis juglandicola (Kaltenback), Macrosiphum rosae (Linnaeus), Myzus cerasi (Fabricius), (Sulzer), Rhopalosiphum maidis (Fitch), Schizaphis graminum (Rondani) and Toxoptera aurantii (Fonscolombe).

Other aphid hosts reported by those listed above are Amphorophora sonchi (Oestlund), Aphis cardui Linnaeus, Aphis lutescens Monell, Aphis rumicis Linnaeus, Aphis viburnicola Gillette, Capitophorus braggii (Gillette), Capitophorus fragaefolii (Cockerell), Hyalopterus artiplicis (Linnaeus), Macrosiphoniella sanborni (Gillette), Macrosiphum euphorbiae (Thomas), Myzocallis alhambra Davidson, Rhopalosiphum fitchii (Sanderson) and Theriophis bella (Walsh). In addition to aphids, Aleyrodidae (whiteflies) have been reported to serve as hosts for the larvae of this syrphid.

Parasites

Allograpta obliqua larvae, and occasionally pupae, are heavily parasitized, even exceeding 50% some years. The hymenopterous parasites that attack Allograpta obliqua as listed in Muesebeck et al. (1951, 1958, 1967) include the following species of Ichneumonidae: Diplazon laetatorius (Fabricius), Diplazon scutellaris (Cresson), Ethelurgus syrphicola (Ashmead), Homotropus pacificus (Cresson), Syrphoctonus flavolineatus (Gravenhorst) and Syrphoctonus fuscitarsus (Provancher); one species of Pteromalidae: Pachyneuron allograptae Ashmead; and one species of Ceraphronidae: Conostigmus timberlakei Kamal.

Selected References

Bhatia ML. 1939. Biology, morphology and anatomy of aphidophagous syrphid larvae. Parasitology 31: 78–129.

Butler GD Jr, Werner FG. 1957. The syrphid flies associated with Arizona crops. Arizona Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletin 132: 1–12.

Campbell RE, Davidson WM. 1924. Notes on aphidophagous Syrphidae of southern California. Bulletin of the Southern California Acadamy of Science 23: 3–9; 59–71.

Curran CH. 1920. Observations on the more common aphidophagous syrphid flies (Dipt.). Canadian Entomologist 53: 53–55.

Davidson WM. 1916. Economic Syrphidae in California. Journal of Economic Entomology 9: 454–457.

Davidson WM. 1919. Notes on Allograpta fracta O.S. (Diptera: Syrphidae). Canadian Entomologist 51: 235–239.

Fluke CL. 1929. The known predacious and parasitic enemies of the pea aphid in North America. Wisconsin Agricultural Experiment Station Research Bulletin 93: 1–47.

Heiss EM. 1938. A classification of the larvae and puparia of the Syrphidae of Illinois exclusive of aquatic forms. University of Illinois Bulletin 36: 1–142.

Jones CR. 1922. A contribution to our knowledge of the Syrphidae of Colorado. Colorado Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 269.

Kamal M. 1939. Biological studies on some hymenopterous parasites of aphidophagous Syrphidae. Egyptian Ministry of Agriculture Technical Service Bulletin 207.

Knowlton GF, Smith CF, Harmston FC. 1938. Pea aphid investigations. Utah Academy of Science Proceedings 15: 73–75.

Krombein KV. et al. 1958. Hymenoptera of America north of Mexico—Synoptic Catalog. USDA Agricultural Monograph No. 2, First Supplement. 305 pp.

Krombein KV, Burks BD. et al. 1967. Hymenoptera of America north of Mexico—Synoptic Catalog. USDA Agricultural Monograph No. 2, Second Supplement. 584 pp.

Metcalf CL. 1912. Life-histories of Syrphidae IV. Ohio Naturalist 12: 533–541.

Metcalf CL. 1916. Syrphidae of Maine. Maine Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 253: 1–264.

Miller RL. 1929. A contribution to the biology and control of the green citrus aphid, Aphis spiraecola Patch. Florida Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletin 203: 431–476.

Muesebeck CFW, Krombein KV, Townes HK, et al. 1951. Hymenoptera of America north of Mexico—Synoptic Catalog. USDA Agricultural Monograph No. 2. 1420 pp.

Say T. 1823. Descriptions of dipterous insects of the United States. Academy of the Natural Sciences of Philadelphia Journal 1: 45–48.

Smith RH. 1923. The clover aphid: Biology, economic relationships and control. Idaho Agricultural Experiment Station Research Bulletin 3: 1–75.

Stone A. et al. 1965. A Catalogue of the Diptera of America north of Mexico. USDA Agricultural Handbook No. 276. 1696 pp.

Thompson WL. 1928. The seasonal and ecological distribution of the common aphid predators of central Florida. Florida Entomologist 11: 49–52.

Tilden JW. 1952. Observations on the habits of certain syrphids (Diptera). Entomological News 63: 39–43.

Wadley FM. 1931. Ecology of Toxoptera graminum, especially as to factors affecting importance in the northern United States. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 24: 325–395.

Weems HV Jr. 1951. Check list of the syrphid flies (Diptera: Syrphidae) of Florida. Florida Entomologist 34: 89–113.

Weems HV Jr. 1954. Natural enemies and insecticides that are detrimental to beneficial Syrphidae. Ohio Journal of Science 54: 45–54.

Williston SW. 1886. Synopsis of the North American Syrphidae. U.S. Natural History Museum Bulletin 31: 1–335.