Introduction

Brazilian peppertree, Schinus terebinthifolia Raddi (Anacardiaceae), is an evergreen shrub or small tree native to Argentina, Paraguay, and Brazil (Ewel et al. 1982). Introduced into Florida as a landscape ornamental in the late 19th century, the popularity of Brazilian peppertree as an ornamental plant was attributed to the numerous bright red drupes (or fruits) produced during the holiday season in Florida. Brazilian peppertree is now recognized as a highly invasive species that quickly dominates disturbed sites as well as natural communities where it forms dense thickets that completely shade out and displace native vegetation. Brazilian peppertree is one of the most widespread of Florida's invasive weed species (Schmitz 1994) and is considered an important threat to Florida biodiversity because it disrupts native plant and animal communities. Birds occasionally become intoxicated following ingestion of the drupes that remain on the trees for several months (Campello and Marsaioli 1974, Kinde et al. 2012). Furthermore, volatiles produced by the flowers can cause sinus and nasal congestion in sensitive humans, and direct contact with the plant's sap can irritate the skin and cause allergic reactions similar to poison ivy. The distribution of Brazilian peppertree extends from the Florida Keys to Nassau County on the east coast and to Okaloosa County on the west coast of Florida (EDDMapS, 2024).

In the 1980s, surveys of the arthropods associated with Brazilian peppertree were conducted in Florida as a first step towards developing a classical (or importation) biological control program against this highly invasive weed (Cassani 1986, Cassani et al. 1989). One of the reasons for conducting these domestic surveys was to conserve limited resources and valuable time that would otherwise be wasted surveying for natural enemies in Brazil that were already established in Florida and having some impact on the weed. Although an extensive list of insects associated with Brazilian peppertree was compiled during these surveys, none of the insects identified severely damaged the drupes of the plant. Because Brazilian peppertree reproduces and is spread mostly by seeds (Langeland et al. 2008, Tobe et al. 1998), the introduction of a natural enemy that preferentially attacked the drupes would contribute to the biological control of this invasive weed by curtailing seed production. The importance of seed predation was recognized in an earlier biological control program against Brazilian peppertree in Hawaii, and eventually led to the introduction of the seed-feeding beetle Lithraeus atronotatus (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) into the islands in the 1950s (Winston et al. 2014).

In 1988, an insect previously unknown to Florida was reared from the drupes of Brazilian peppertree collected in Palm Beach County (Habeck et al. 1989). The insect was subsequently identified as Megastigmus transvaalensis, a phytophagous (or plant feeding) seed chalcid wasp (Figure 1). The Brazilian peppertree seed chalcid is an adventive (or immigrant) species that probably entered into Florida as a contaminant of the fruits that are sold as pink peppercorns in gourmet food stores (Habeck et al. 1989). Other likely modes of introduction into Florida include wasp-infested drupes of Brazilian peppertrees imported as ornamental plants (Grissell and Hobbs 2000), or infested drupes of Schinus spp. sold at craft stores for holiday decorations (Wheeler et al. 2001).

Credit: D. H Habeck, UF/IFAS

Distribution

Megastigmus transvaalensis was originally described from South Africa (Boucek 1978) and was probably introduced accidentally into the US from Reunion or Mauritius via France in Brazilian peppertree seeds sold as spices in some food shops (Habeck et al. 1989). Worldwide, the Brazilian peppertree seed chalcid has been reared from drupes of Schinus spp. collected in Argentina (Wheeler et al. 2001), Brazil (Grissell and Hobbs 2000), the Canary Islands (Grissell 1979), Réunion, Mauritius (Habeck et al. 1989), and South Africa (Iponga et al. 2008; Magengelele and Martin 2023), where it is considered a native species (Grissell 1979, Scheffer and Grissell 2003).

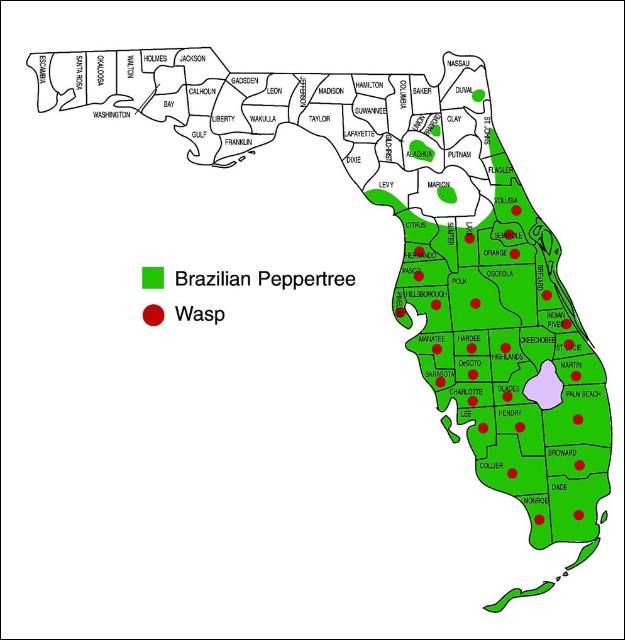

In the United States, the wasp has been reported from California (Harper and Lockwood 1961, Scheffer and Grissell 2003), Hawaii (Beardsley 1971, Scheffer and Grissell 2003), and Florida (Habeck et al. 1989, Scheffer and Grissell 2003). In Florida, the insect has been recovered from Brazilian peppertree drupes collected in the following counties: Brevard, Broward, Charolette, Collier, Dade, Desoto, Glades, Hardee, Hendry, Hernando, Highlands, Hillsborough, Lake, Lee, Martin, Monroe, Orange, Palm Beach, Pasco, Pinellas, Polk, Sarasota, Seminole, St. Lucie, and Volusia (Figure 2) (Wheeler et al. 2001).

Credit: Stephan McJonathan, FDACS-DPI

Description

The following descriptions of the life stages of the Brazilian peppertree seed chalcid were compiled from two sources. The description of the adult stage is derived from the original description of the wasp by Hussey (1956). However, none of the immature stages of the Brazilian peppertree seed chalcid have been described in the scientific literature. The only published information on the immature stages of Megastigmus wasps is that of Megastigmus nigrovariegatus Ashmead, a Nearctic species whose immature stages were described and illustrated by Milliron (1949). Because the immature stages of the Brazilian peppertree seed chalcid are probably very similar in appearance to those of Megastigmus nigrovariegatus, the descriptions of the developmental stages of the Brazilian peppertree seed chalcid are based on those of Megastigmus nigrovariegatus.

Adults

Adults of the Brazilian peppertree seed chalcid are pale yellow-brown in color. Males range in size from 2.3 to 2.9 mm whereas females tend to be larger. Body length for female wasps ranges from 3.1 to 3.4 mm; the length of the abdomen and ovipositor range in size from 1.2 to 1.4 and 1.5 to 1.9 mm, respectively. Almost half of the overall body length in females is attributed to the ovipositor. Gravid females of Megastigmus nigrovariegatus normally contain 10 to 25 eggs (Milliron 1949). Presumably, females of the Brazilian peppertree seed chalcid are capable of producing the same number of eggs.

Eggs

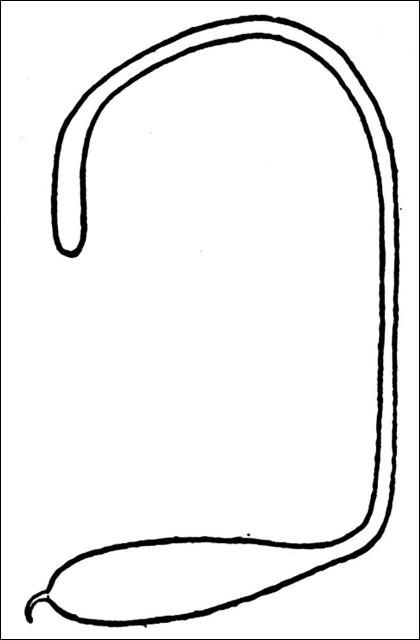

The egg of Megastigmus nigrovariegatus (Figure 3) is composed of three parts: a long narrow anterior stalk, an elongate-oval body, and a short spur-like posterior stalk (Milliron 1949). Individual eggs range in size from 0.99 to 1.5 mm in length, are grayish white in color, and the entire surface is shiny and smooth lacking ornamentation. Eggs of the Brazilian peppertree seed chalcid probably are similar in shape, size and texture.

Credit: H. E. Milliron (1949)

Larvae

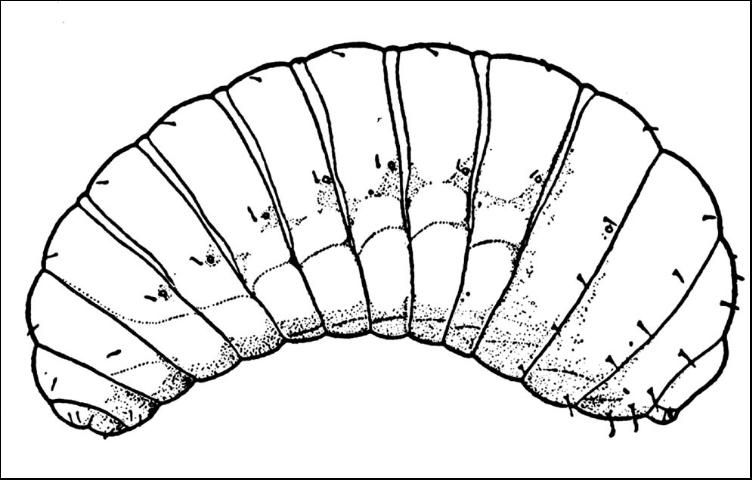

The Brazilian peppertree seed chalcid presumably has five instars, the same number of instars reported for Megastigmus nigrovariegatus (Milliron 1949). Although more than one egg may be deposited inside a drupe, the larvae are cannibalistic and usually only one larva is capable of completing its development. Occasionally, a single drupe will support complete development of two larvae.

Credit: H. E. Milliron (1949)

Pupa

After the larvae of the Brazilian peppertree seed chalcid attain their maximum size, they transform into the pupal stage (Figure 5) and remain in a prolonged diapause (or resting) period for several months. Adult emergence seems to be photoperiod induced and occurs when the drupes containing viable pupae are exposed to short day length (12-hour photoperiod), which coincides with the flowering phase of Brazilian peppertree during the fall of the year (Wheeler et al. 2001).

Credit: H. E. Milliron (1949)

Life Cycle

The complete life history of the Brazilian peppertree seed chalcid has not been investigated but a generalized biology of seed-attacking Megastigmus wasps was described by (Milliron 1949). After mating, the female deposits an egg inside the developing seed where all life stages of the wasp develop. The egg incubation period is short, and larvae probably hatch in four to five days. After several months, a single adult emerges from the seed. However, this period may be shorter in Megastigmus transvaalensis as adults emerged a few weeks after flower initiation (G.S. Wheeler, unpublished data). Prior to emergence of the adult wasp, it is difficult to distinguish between attacked and unattacked drupes as there apparently is no external evidence of the insect developing inside the seed.

The Brazilian peppertree seed chalcid presumably has two generations per year that are synchronized with the winter and spring drupe production periods of its host plant. The sex ratio of wasps emerging from drupes of Brazilian peppertree averaged over a two-year period was 2:1 (females: males) (Wheeler et al. 2001).

Host Plants

The Brazilian peppertree seed chalcid is capable of developing and reproducing on plants in the genera Rhus and Schinus. The host range of the insect includes at least six Rhus spp. native to Africa, including Rhus angustifolia L., Rhus laevigata L., Rhuslancea L.f., Rhus natalensis (Krauss), Rhus tripartita (Ucria) Grande, and Rhus vulgaris Meikle (Hussey 1956, Grissell 1979, Yoshioka and Markin 1991, Scheffer and Grissell 2003, Magengelele and Martin, 2023). Schinus molle L. and Schinus terebinthifolia, which are both native to South America, are considered novel host plants (Hussey 1956, Habeck et al. 1989, Scheffer and Grissell 2003). No native members of the Anacardiaceae found within the Florida distribution of Brazilian peppertree are attacked by the wasp despite numerous attempts to rear the insect from the drupes of high-risk species like winged sumac, Rhus copallinum L. (Wheeler et al. 2001).

Importance

Megastigmus transvaalensis inhibits seed production and may reduce the spread of Brazilian peppertree into natural areas where this invasive weed is displacing native species. In a two-year study, up to 31% and 76% of the Brazilian peppertree drupes were damaged by the wasp during the winter and spring fruit production periods, respectively (Wheeler et al. 2001). The drupes that are damaged by the wasp also fail to germinate. It remains to be determined why a higher incidence of wasp-damaged drupes was observed in Brazilian peppertree plants occurring north of Lake Okeechobee and in more inland rather than coastal sites (Wheeler et al. 2001).

Selected References

Beardsley JW. 1971. Megastigmus sp. Proceedings of the Hawaiian Entomological Society 21: 28.

Boucek Z. 1978. A study of the nonpodagrionine Torymidae with enlarged hind femora, with a key to the African genera (Hymenoptera). Journal Entomological Society South Africa 41: 91–134.

Campello JP, Marsaioli AJ. 1974. Triterpenes of Schinus terebinthifolius. Phytochemistry 13: 659–660.

Cassani JR. 1986 Arthropods on Brazilian peppertree Schinus terebinthifolius (Anacardiaceae), in south Florida. Florida Entomologist 69: 184–196.

Cassani JR, Maloney DR, Habeck DH, Bennett FD. 1989. New insect records on Brazilian peppertree (Anacardiaceae), in south Florida. Florida Entomologist 72: 714–716.

Ewel J, Ojima DS, Karl DA, DeBusk WF. 1982. Schinus in successional ecosystems of Everglades National Park T-676. National Park Service, South Florida Research Center, Everglades National Park, Homestead, FL.

EDDMapS. 2024. Early Detection & Distribution Mapping System. The University of Georgia - Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health. Available online at http://www.eddmaps.org/; last accessed May 19, 2024.

Grissell EE, Hobbs KR. 2000. Megastigmus transvaalensis (Hussey) (Hymenoptera: Torymidae) in California: Methods of introduction and evidence of host switching, pp.265-278. In The Hymenoptera: Evolution, Biodiversity and Biological Control. CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne, Australia.

Grissell EE. 1979. Subfamily Megastigminae, pp. 765–767. In Krombein KV, Hurd HDJ (eds.), Catalog of Hymenoptera in America North of Mexico. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC.

Habeck DH, Bennett FD, Grissell EE. 1989. First record of a phytophagous seed chalcid from Brazilian peppertree in Florida. Florida Entomologist 72: 378–379.

Harper RW, Lockwood S. 1961. Forty-first annual report, Bureau of Entomology. California Department of Agriculture Bulletin 50: 127–129.

Hussey NW. 1956. A new genus of African Megastigminae (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London (B) 25: 157–162.

Igonga DM, Cuda JP, Milton SJ, Richardson DM. 2008. Megastigmus wasp damage to seeds of Schinus molle, Peruvian pepper tree, across a rainfall gradient in South Africa: implications for invasiveness. African Entomology 16: 127–131.

Kinde H, Foate E, Beeler E, Uzal F, Moore J, Poppenga R. 2012. Strong circumstantial evidence for ethanol toxicosis in cedar waxwings (Bombycilla cedrorum). Journal of Ornitholology. (DOI: 10.1007/s10336-012-0858-7).

Langeland K A, Cherry HM, McCormick CM, Craddock Burks KA. 2008. Identification & biology of nonnative plants in Florida's natural areas, 2nd edition. University of Florida, Gainesville. IFAS Communication Services. 193 pp.

Magengelele NL, Martin GD. 2023. Distribution and impact of the native South African wasp, Megastigmus transvaalensis (Hussey, 1956) (Hymenoptera: Torymidae) on the invasive Schinus terebinthifolia Raddi (Anacardiaceae) in South Africa. African Entomology 31:1-3.

Milliron HE. 1949. Taxonomic and biological investigations in the genus Megastigmus with particular reference to the taxonomy of the Nearctic species (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea: Callimomidae). American Midland Naturalist 41: 257–420.

Scheffer SL, Grissell EE. 2003. Tracing the geographical origin of Megastigmus transvaalensis (Hymenoptera: Torymidae): an African wasp feeding on a South American plant in North America. Molecular Ecology 12: 415–421.

Schmitz DC. 1994. The ecological impact of non-indigenous plants in Florida, pp. 10–17. In An Assessment of Non-indigenous Species in Florida's Public Lands. Technical Report TSS-94-100, Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Tallahassee, FL.

Tobe JD. et al. 1998. Florida Wetland Plants: An Identification Manual. Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Tallahassee, FL.

Wheeler GS, Massey LM, Endries M. 2001. The Brazilian peppertree drupe feeder Megastigmus transvaalensis (Hymenoptera: Torymidae): Florida distribution and impact. Biological Control 22: 139–148.

Winston RL, Schwarzländer M, Hinz HL, Day MD, Cock MJW, Julien MH. (eds.). 2014. Biological Control of Weeds: A World Catalogue of Agents and Their Target Weeds, 5th edition, FHTET-2014-04. Morgantown, WV: USDA Forest Service, Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team. 838 pp.

Wunderlin RP, Hansen BF, Franck AR, Essig FB2017. Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants (https://florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/). [Landry SM, Campbell KN (application development), USF Water Institute.] Institute for Systematic Botany, University of South Florida, Tampa (accessed 20 Jun 2017).

Yoshioka ER, Markin GP. 1991. Efforts of biological control of Christmas berry Schinus terebinthifolius in Hawaii, pp. 377-385. In T. D. Center et al. (eds.), Proceedings of the Symposium on Exotic Pest Plants, 2–4 November, 1988, Miami, FL. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Washington, DC.