Introduction

The introduced tree Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cav.) S.T. Blake (Myrtaceae), known as paperbark, punktree, or melaleuca, is an aggressive invader of many South Florida ecosystems, including the Everglades. Melaleuca is considered a pest because it displaces native vegetation and degrades wildlife habitat; it also creates fire hazards and can cause human health problems (Rayamajhi et al. 2002). The USDA/ARS with federal and state permission introduced the psyllid Boreioglycaspis melaleucae (Figure 1) into Broward County, Florida, in February 2002 as a potential biocontrol agent of melaleuca.

Credit: Susan Wineriter, USDA

Distribution

B. melaleucae has been collected from all states in its native Australia except South Australia (Burkhardt 1991). Specimens released in Florida originated from southeastern Queensland. As of October 2002, the melaleuca psyllid had been released in five Florida counties—Broward, Collier, Lee, Miami-Dade, and Palm Beach—and is known to have established in all counties except Palm Beach. It eventually spread naturally to all 22 central and south Florida counties where melaleuca infestations occur.

Description

Adults

Boreioglycaspsis adults (Figure 2) are small, about 3 mm long, and inconspicuous, pale yellow-orange to white in color with gray to black markings. The tips of the antennae are gray to black, and the wings are transparent with yellow veins. The compound eyes are usually pale green with a distinctive dark spot within, but various shades of red have been observed in the laboratory; its three ocelli are bright orange, the dorsal two being the most obvious. Two prominent finger-shaped appendages or genae (Figure 3) extend outward and slightly downward from beneath the eyes. When resting or feeding, the body is parallel to leaf or stem surfaces unlike, for example, the invasive Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri, that holds its body at a 45° angle.

Credit: Susan Wineriter, USDA

Credit: Jeffrey Lotz, DPI

Males and females can be distinguished easily from one another by the shape of their abdomens and by the male genitalia. The abdomen of a male is shaped like an elongated isosceles triangle when viewed from above and terminates in distinctive claspers, easily apparent when viewed laterally. The abdomen of a female is more rectangular, gradually tapering to the tip; the pleural membranes usually are expanded, partially visible from above, bulging with eggs. Females generally are larger than males. Adults frequently drag their hind legs when walking, and jump or fly when disturbed.

Nymphs

Nymphs, except for neonates (or newly hatched insects), are sedentary unless disturbed. First instars are pale yellow with no markings, but by the 5th instar they have gray to black markings on the body (Figure 4). Nymphs secrete conspicuous white waxy filaments from a dorsal caudal plate while feeding. The filamentous wax loosely covers their bodies (Figure 5). Branches and leaves become covered with the waxy filaments creating a flocculence (wool-like tufts) that indicates a heavy infestation (Figure 6). Rain will wash away the flocculence, but nymphs will soon secrete more. In addition, they produce copious amounts of honeydew held externally in balloon-like waxy membranes; nymphs discard honeydew filled spheres nearby. Adults also excrete waxy spheres of honeydew, but they flip them away from their immediate area.

Credit: Jeffrey Lotz, DPI

Credit: Susan Wineriter, USDA

Credit: Susan Wineriter, USDA

Eggs

Eggs are pale to bright yellow and are laid singly or in groups on both leaves and stems of melaleuca (Figure 7). They are held on by a narrow projection or pedicel inserted into the leaf.

Credit: Susan Wineriter, USDA

Life History

Females deposit approximately 80 eggs (Rayamajhi et al. 2002), and nymps hatch in two to three weeks. The nymphal stage (five instars) requires three to four weeks. Following its release in Florida, B. melaleucae established quickly (Center et al. 2006) and dispersed throughout melaleuca's range at a rate of approximately 7 km/year (Balentine et al. 2009). The insect is now widely established, with enormous populations developing during the spring dry season in all habitat types. However, populations decline during the summer, probably due to high temperatures rather than precipitation (Chiarelli et al. 2011).

Importance

Both adults and nymphs feed on melaleuca, causing high mortality of seedlings and premature leaf drop from mature trees (Franks et al. 2006; Morath et al. 2006). High psyllid infestations also increase mortality of coppicing (resprouting) stumps (Center et al. 2007). The melaleuca snout weevil, Oxyops vitiosa, the first insect released for biological control of melaleuca, cannot establish at permanently flooded melaleuca sites because of the soil requirement for pupation. Under these conditions, the psyllid B. melaleucae is still capable of severely damaging melaleuca because this insect completes its life cycle entirely in the tree canopy.

Hosts

In Australia, B. melaleucae is known to occur on four species of closely related melaleucas in the Melaleuca leucadendra complex. These are Melaleuca argentea, Melaleuca leucadendra, Melaleuca nervosa, and Melaleuca quinquenervia. None of these species is native to the New World. In addition, in host range studies conducted at the USDA/ARS Australian Biological Control Laboratory, it completed development on Melaleuca viridiflora and Melaleuca nodosa, also native to Australia. In host-range tests conducted at the FDACS Florida Biological Control Laboratory, it completed development one time on bottlebrush, Callistemon (= Melaleuca) citrinus, the broad-leaved form, an introduced ornamental.

Survey and Detection

In order to survey for B. melaleucae, look for flocculence on the newest growth of the host trees. Adults can be collected using a beat sheet and an insect aspirator or with yellow sticky insect trapping cards.

Similar Species in Florida

Boreioglycaspis melaleucae is distinctive because of its long genae (Figure 8), which are nearly as long as the vertex. The only other species in Florida with such conspicuous long genae is the invasive pest species, Glycaspis brimblecombei Moore, found on introduced eucalyptus (Halbert et al. 2001). When alive, the green color morph (Figure 9) would not be confused with B. melaleucae, but the brown color morph (Figure 10) could be. When dead, G. brimblecombei color morphs are more similar and both could be confused with B. melaleucae.

Credit: Jeffrey Lotz, DPI

Credit: Susan Wineriter, USDA

Credit: Susan Wineriter, USDA

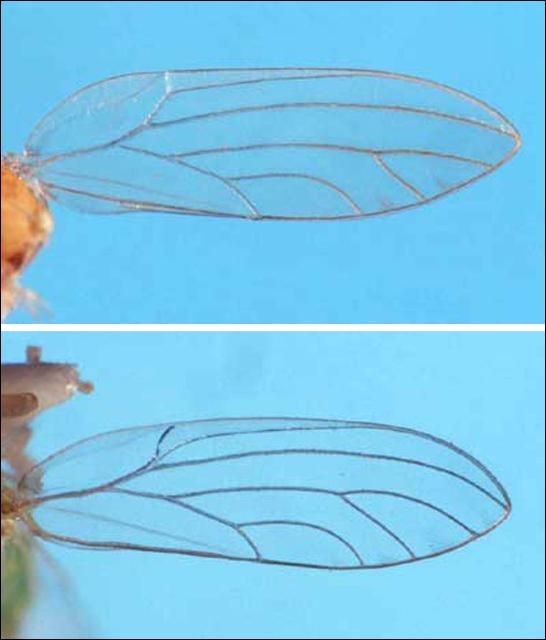

Dead adults can be separated by the following couplet:

1. Antennae less than half as long as body, excluding wings; branch of the median wing vein distal to the point at which Cu1a intersects the edge of the wing . . . . . . . . . B. melaleucae

1'. Antennae about 3/4 as long as body, excluding wings; branch of median wing vein proximal to the point at which Cu1a intersects the edge of the wing . . . . . . . . G. brimblecombei

Credit: Susan Wineriter, USDA

Nymphs should not be confused on plants: Glycaspis brimblecombei nymphs form lerps (a shelter produced from a carbohydrate secretion from the anus), whereas B. melaleucae nymphs are just covered with fuzzy wax. Another introduced but not invasive psyllid, Blastopsylla occidentalis Taylor, found on introduced eucalpytus, is morphologically quite distinctive from B. melaleucae, but the overall appearance of the adult and similar nymphal flocculence could cause confusion. This psyllid is about half the size of B. melaleucae and has no prominent genae.

Management

Biological Control

The psyllid should be a major pest of Melaleuca quinquenervia only; and therefore, there should be no need for biological control. One Australian nymphal parasitoid, Psyllaephagus sp., (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae) is known from B. melaleucae (Purcell et al. 1997) and was screened out of shipments sent to Florida. No Psyllaephagus spp. occur in Florida, and native Florida psyllid parasites are unlikely to cross-over.

Chemical Control

Melaleuca quinquenervia is a federally and state-listed noxious weed and legally cannot be purchased or possessed. However, landowners of older large melaleuca trees in urban areas may be distressed by the damage psyllids cause to their trees or by the abundance of flocculence and honeydew produced by nymphs. While homeowners should be encouraged to remove trees, they may not be willing to do so. Chemicals labeled for psyllids may be warranted in this instance. Strong sprays of water will wash the nymphs from the leaves.

Selected References

Balentine KM, Pratt, PD, Dray, Jr. FA, Rayamajhi MB, Center T. D. 2009. Geographic distribution and regional impacts of Oxyops vitiosa (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) and Boreioglycaspis melaleucae (Hemiptera: Psyllidae), biological control agents of the invasive tree Melaleuca quinquenervia. Environmental Entomology 38: 1145–1154.

Burckhardt D. 1991. Boreioglycaspis and spondyliaspidine classification (Homoptera: Psylloidea). The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 39: 15–52.

Center TD, Pratt PD, Tipping PW, Rayamajhi M B, Van TK, Wineriter SA, Dray J, Purcell M. 2006. Field colonization, population growth, and dispersal of Boreioglycaspis melaleucae Moore, a biological control agent of the invasive tree Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cav.) Blake. Biological Control 39:363–374.

CenterTD, Pratt PD, Tipping PW, Rayamajhi MB, Van TK, Wineriter SA, Dray FA. 2007. Initial impacts and field validation of host range for Boreioglycaspis melaleucae Moore (Hemiptera: Psyllidae), a biological control agent of the invasive tree Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cav.) Blake (Myrtales: Myrtaceae: Leptospermoideae). Environmental Entomology 36: 569–576.

Chiarelli RN, Pratt PD, Silvers CS, Blackwood JS, Center TD. 2011. Influence of temperature, humidity, and plant terpenoid profile on life history characteristics of Boreioglycaspis melaleucae (Hemiptera: Psyllidae), a biological control agent of the invasive tree Melaleuca quinquenervia. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 104: 488–497.

Franks SJ, Kral, AM, Pratt PD. 2006. Herbivory by introduced insects reduces growth and survival of Melaleuca quinquenervia seedlings. Environmental Entomology 35: 366–372.

Halbert SE, Gill RJ, Nisson JN. 2001. Two Eucalyptus psyllids new to Florida (Homoptera: Psyllidae). Florida Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry, Gainesville, Entomology Circular No. 407: 1–2.

Hodkinson I D. 1974. The biology of Psylloidea (Homoptera): a review. Bulletin of Entomological Research 64: 325–339.

Moore KM. 1964. Observations of some Australian forest insects. 19. Additional information on the genus Glycaspis (Homoptera: Psyllidae); erection of a new subgenus and descriptions of six new species. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 89: 221–234.

Moore KM. 1970. Observations of some Australian forest insects. 23. A revision of the genus Glycaspsis (Homoptera: Psyllidae) with descriptions of seventy-three new species. Australian Zoologist 15: 248–342.

Morath SU, Pratt PD, Silvers CS, Center TD. 2006. Herbivory by Boreioglycaspis melaleucae (Hemiptera: Psyllidae) accelerates foliar senescence and abscission in the invasive tree Melaleuca quinquenervia. Environmental Entomology 35: 1372–1378.

Purcell MR, Balciunas JK, Jones P. 1997. Biology and host-range of Boreioglycaspis melaleucae (Hemiptera: Psyllidae), potential biological control agent for Melaleuca quinquenervia (Myrtaceae). Environmental Entomology 26: 366–372.

Rayamajhi MB, Purcell MF, Van TK, Center TD, Pratt PD, Buckingham GR. 2002. Australian paperbark tree (Melaleuca), pp. 117–130. In Van Driesche R, Blossey B, Hoddle M, Lyon S, and Reardon R (eds.), Biological Control of Invasive Plants in the Eastern United States. USDA Forest Service Publication FHTET-2002-04. USDA Forest Service, Morgantown, West Virginia.

Wineriter SA, Buckingham GR, Frank JH. 2003. Host-range of Boreioglycaspis melaleucae Moore (Hemiptera: Psyllidae), a potential biocontrol agent of Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cav.) S.T. Blake (Myrtaceae), under quarantine. Biological Control 27: 273–292.