The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

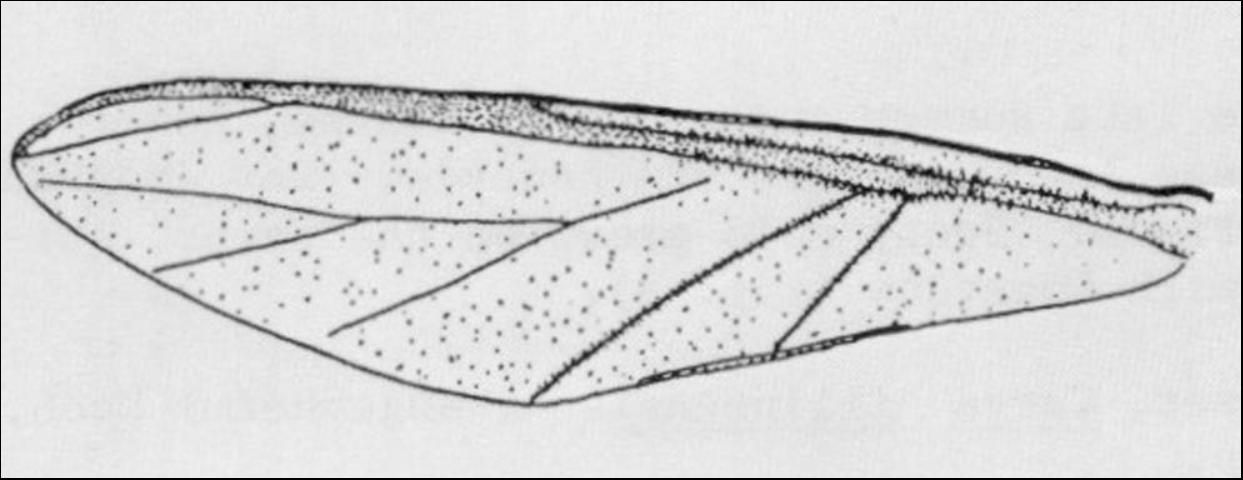

This bark-feeding aphid was first described by Harris (1841) as Aphis caryae from pignut hickory, Carya glabra (= porcina) (Mill.) Sweet, in Massachusetts. It is the largest aphid that occurs in the United States, and it was probably this species that was reported by Thomas (1879) from limbs of pignut hickory in Illinois. Weed (1891) described its various forms and gave a short note on its biology. Wilson (1909) described the genus Longistigma for this species because of the extremely long slender stigma that extends around the end of the wing.

Credit: Louis Tedders, USDA ARS, courtesy of ForestryImages.org

Distribution

Longistigma caryae has been reported from Alabama, Arkansas, Arizona, California, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

Description

Apterous (wingless) viviparous female: body 6 mm (~1/4 in)long, abdomen 3.5 mm (~1/8 in) in diameter, antennae 3 mm (~1/8 in) long, posterior legs 9 mm (~1/3 in) long. Light to dark brown except cornicles and a few small spots on the abdomen; tips of femora, tibia and tarsi black. Cornicles very short and truncate. Rostrum extending to posterior coxae. Body, legs and antennae with long, light brown hairs. Antennal segment III equal to IV plus V; VI short, with unguis thumb-shaped.

Credit: UF/IFAS

Alate (winged) viviparous female: body 6 mm (~1/4 in) long, abdomen 3 to 5 mm (~1/8 to 3/16 in) in diameter, head to tip of folded wings 10 mm (~3/8 in); wing expanse 18 mm (~3/4 in), antennae 3 mm (~1/8 in), posterior legs 11 mm (7/16 in). Head and thorax bluish-black; antennae and cornicles black; dorsum of abdomen whitish with 2 rows of black spots on each side of the median line and a transverse series of small, black dots on each segment. Cornicles short and truncate. Tips of femora, tibia and tarsi black. Body, legs and antennae covered with long brown hairs. Wings dusky, especially toward base. Oviparous females do not differ in appearance from viviparous females.

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Hosts

Basswood—Tilia spp., hickory—Carya spp., oak—Quercus spp., pecan—Carya illinoensis (Wangenheim) Koch, sycamore—Platanus spp., walnut—Juglans spp. and wax myrtle—Myrica cerifera (Barnard and Dixon, Mueller 2002).

Economic Importance

During the late summer and autumn months, aphids excrete large amounts of a sticky, clear liquid while feeding. This is known as honeydew and can form a sticky coating on automobiles, picnic tables, lawn furniture, and plants underneath trees where the aphids are feeding. Soon sooty mold, which is grey-black in color, begins to grow on the sugar-rich honeydew. While sooty mold does not directly damage plants, it blocks sunlight and disrupts photosynthesis, contributing to reduced plant vigor. Sooty mold can also damage the finish on cars, chairs, tables, or other objects.

Survey and Detection

Look for sooty mold on any of the host plants. Check the tree bark for large dark aphids during the summer and early autumn.

Management

For management information please contact your local UF/IFAS Extension agent: https://sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu/find-your-local-office/.

Selected References

Barnard EL, Dixon WN. (October 1983). Giant bark aphid. Insects and Diseases: Important Problems of Florida's Forest and Shade Tree Resources. No longer online.

Harris TW. 1841. A Report on the insects of Massachusetts, injurious to vegetation. (1842 Reprint: A treatise on some of the insects of New England, which are Injurious to vegetation. Cambridge), 459 p.

Mueller CW. (March 2002). Giant bark aphids. Horticulture Update. https://tfsweb.tamu.edu/GiantBarkAphids/ (September 2024).

Thomas C. 1879. Eighth report of the state entomologist on the noxious and beneficial insects of the state of Illinois. Third Annual Report, 212 p.

Weed CM. 1891. Fifth contribution to a knowledge of certain little-known Aphididae. Insect Life 3: 285–293.

Wilson HF. 1909. Notes on Lachnus caryae Harris under a new name. Canadian Entomologist 41: 385–387.