The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

The Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus (Skuse), was first documented in the United States in Texas in 1985 (Sprenger and Wuithiranyagool 1986). A year later, the Asian tiger mosquito was found in Florida at a tire dump site near Jacksonville (O'Meara 1997). Since that time, this species has spread rapidly throughout the eastern states, including all of Florida's 67 counties (O'Meara 1997). The arrival of Aedes albopictus has been correlated with the decline in the abundance and distribution of the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti. There are a number of possible explanations for the competitive exclusion of Ae. aegypti by Ae. albopictus. The decline is likely due to a combination of (a) sterility of offspring from interspecific matings, (b) reduced fitness of Aedes aegypti from parasites brought in with Aedes Albopictus, and (c) superiority of Aedes albopictus in larval resource competition (Lounibos 2002). The distribution of Ae. aegypti currently is limited to urban habitats in southern Texas, Florida and in New Orleans (Lounibos 2002).

Aedes albopictus is a competent vector of many viruses including dengue fever (CDC 2001), Eastern equine encephalitis virus (Mitchell et al. 1992), and zika virus (CDC 2019). Its life cycle is closely associated with human habitat, and it breeds in containers with standing water, often tires or other containers. It is a daytime feeder and can be found in shady areas where it rests in shrubs near the ground (Koehler and Castner 1997). Aedes albopictus feeding peaks in the early morning and late afternoon; it is an opportunistic and aggressive biter with a wide host range including man, domestic and wild animals (Hawley 1988).

Credit: J. L. Castner, UF/IFAS

Distribution

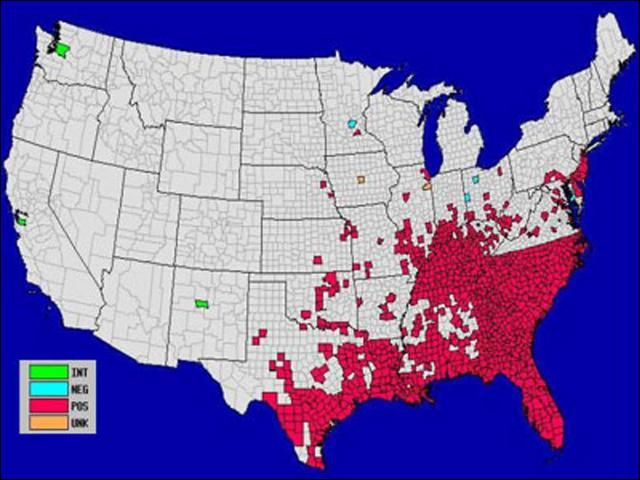

The distribution of Aedes albopictus is subtropical, with a temperate distribution in North America, and in the United States has expanded rapidly over the past few years. This species was first documented in Texas in 1985 and is currently established in 866 counties in 26 states (CDC 2001).

Credit: Center for Disease Control

The worldwide distribution includes most of Asia and covers tropical and subtropical regions worldwide with introductions into the Caribbean (Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 1989). Endemic to Asia and the Pacific islands, the range has greatly expanded to include North and South America, Africa and Europe (O'Meara 1997).

Description

Adult Aedes albopictus are easily recognized by the bold black shiny scales and distinct silver white scales on the palpus and tarsi (Hawley 1988). The scutum (back) is black with a distinguishing white stripe down the center beginning at the dorsal surface of the head and continuing along the thorax. It is a medium-sized mosquito (approximately 2.0 to 10.0 mm (0.08 to 0.4 in), males are on average 20% smaller than females). Differences in morphology between male and female include the antennae of the male are plumous and mouthparts are modified for nectar feeding. The abdominal tergites are covered in dark scales. Legs are black with white basal scales on each tarsal segment. The abdomen narrows into a point characteristic of the genus Aedes. Field identification is very easy because of these distinct features.

For a pictorial key (that includes the larval, pupal and adult stage for many common Florida mosquitoes) to identify Ae. albopictus and other mosquitoes of Florida, see: https://fmel.ifas.ufl.edu/media/fmelifasufledu/key/pdf/atlas.pdf.

Credit: UF/IFAS

Life Cycle

Aedes albopictus overwinter in the egg stage in temperate climates (Lyon and Berry 2000) but are active throughout the year in tropical and subtropical habitats. Eggs are laid singly on the sides of water-holding containers such as tires, animal watering dishes, birdbaths, flowerpots and natural holes in vegetation (Hawley 1988). They are black and oval with a length of 0.5 mm (0.02 in). Eggs can withstand desiccation up to one year. Larval emergence occurs after rainfall raises the water level in the containers. The eggs may require several submersions before hatching (Hawley 1988). Additionally, oxygen (O2) tension greatly affects egg hatch (Hawley 1988). A number of studies have shown low O2 tension stimulates the hatching of Aedes albopictus eggs and is a more important factor than flooding or temperature on inducing egg hatch (Hawley 1988). Development is temperature dependent, but the larvae usually pupate after five to ten days and the pupal stage lasts two days (Hawley 1988). Larvae, also called wigglers, are active feeders. They feed on fine particulate organic matter in the water. The larvae use a breathing siphon to acquire oxygen and must periodically come to the surface to do so. The larvae develop through four instars prior to pupation. Unlike many other insects, the pupae of mosquitoes are active and short-lived. They do not feed but can move about. For more information see the Public Health Pesticide Applicator Training Manual - Mosquitoes.

Credit: Michele M. Cutwa, UF/IFAS

Credit: Michele M. Cutwa, UF/IFAS

Medical Significance

Aedes albopictus is known to be a competent laboratory vector of more than 30 viruses. Of these 30 only a few are known to affect humans; they are eastern equine encephalitis (EEE), Cache Valley virus, dengue, St. Louis and LaCrosse encephalitis viruses (CDC 2001, Hawley 1988), and zika virus (CDC 2019). Despite being featured as the ferocious tiger mosquito (ABC news 2001) it has not been found to be a significant health concern and is in fact a less efficient vector than other Aedes mosquitoes. Aedes albopictus has been implicated in the transmission of dengue, but this is not a major vector.

Aedes aegypti is the most competent vector of dengue virus (Gulber 1998). The Asian tiger mosquito is considered a maintenance vector and occasionally is involved with dengue transmission in Asia (CDC 2001). Dengue virus was isolated from collections of Aedes albopictus in Mexico after an epidemic (Lounibos 2002). Despite occasional viral isolations, there is no evidence that this mosquito is a public health threat in the United States. There is one isolated incidence in Polk County, Florida where Aedes albopictus was implicated in the transmission of eastern equine encephalitis in 1991 (Moore and Mitchell 1997). More recently there was an isolation of La Crosse virus found in field collected Aedes albopictus in North Carolina (Gerhardt et al. 2001). The implications of these findings are that this mosquito should be monitored for disease activity, but at this time should not be considered a public health threat.

Surveillance and Management of Aedes albopictus

After entering the United States twenty years ago, Aedes albopictus has spread throughout much of the eastern states. The mosquito was most likely transported along highways and other major roadways in shipments of used tires imported from other countries for retreading. In January 1988, the U.S. Public Health Service required all used tires entering the U.S. from known endemic countries be dry, clean and treated with fumigants (Moore and Mitchell 1997). Surveillance for Aedes albopictus was initiated in 1986 and this species continues to be monitored by public health agencies (Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 1989).

Management of adult populations is more complicated than for other species due to insecticide tolerance to malathion, temephos and bediocarb (Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 1987). In many suburban areas, complaints to health departments are more frequently due to Aedes albopictus than in former years when Aedes aegypti was the most commonly reported nuisance mosquito (Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 1989). Source reduction is an effective way for people in the community to manage the populations of many mosquitoes, especially container breeding species such as the Asian tiger. The removal of mosquito breeding habitat can be an effective method for mosquito control (Dame and Fasulo 2003).

Eliminate any standing water on the property, change pet watering dishes, overflow dishes for potted plants, and bird bath water frequently. Do not allow water to accumulate in tires, flower-pots, buckets, rain barrels, gutters etc. Use personal protection to avoid mosquito bites. Long sleeves and insect repellent such as DEET will reduce exposure to bites. The Asian tiger mosquito is a day biter with feeding peaks early morning and late afternoon, so by limiting outdoor activities during crepuscular periods (dawn and dusk) when mosquitoes are generally most active, bites can be avoided.

For more information please see

Mosquitoes and Their Control: Intergrated Pest Management for Mosquito Reduction around Homes and Neighborhoods (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in1045)

Use and Application of DEET Repellent (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/IG122)

Selected References

ABC news. 2001. Ferocious tiger mosquito invades the United States. July 30.

Centers for Disease Control. 2019. Zika transmission. https://www.cdc.gov/zika/causes/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/zika/prevention/transmission-methods.html. (7 June 2021).

Centers for Disease Control. 2001. Information on Aedes albopictus. Arboviral Encephalitides. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/arbor/albopic_new.htm (21 January 2004).

Centers for Disease Control. 1986. Epidemiologic notes and reports Aedes albopictus Introduction—Texas. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 35:141–2.

Centers for Disease Control. 1987. Current trends update: Aedes albopictus Infestation—United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 36:769–773.

Centers for Disease Control. 1989. Update: Aedes albopictus infestation—United States, Mexico. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 38:440, 445–446.

Cutwa MM, O'Meara GF. Photographic guide to the common mosquitoes of Florida. https://fmel.ifas.ufl.edu/media/fmelifasufledu/key/pdf/atlas.pdf

Dame D, Fasulo TR. 2003. Mosquitoes. Public Health Pesticide Applicator Training Manual. https://ccmedia.fdacs.gov/content/download/109002/file/Public-Health-Manual-2023.pdf

Gerhardt RR, Gottfried KL, Apperson CS, Davis BC, Erwin PC, Smith AB, Panella NA, Powell EE, Nasci RS. 2001. First isolation of La Crosse Virus from naturally infected Aedes albopictus. Emerging Infectious Diseases 7:807–811.

Gubler DJ. 1998. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 480–496.

Hawley WA. 1988. The biology of Aedes albopictus. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association. Supplement #1 p. 1–40.

Koehler PG, Castner JL. 1997. Bloodsucking insects. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/IN019 (21 January 2004).

Lounibos PL. 2002. Invasions by insect vectors of human disease. Annual Review of Entomology 47:233–266.

Lyon WF, Berry RL. 1991. Asian tiger mosquito. Ohio State University Extension Fact Sheet HYG-2148-98.

Mitchell CJ, Niebylski ML, Smith GC, Karabatsos N, Martin D, Mutebi JP, Craig GB Jr, Mahler MJ. 1992. Isolation of eastern equine encephalitis virus from Aedes albopictus in Florida. Science 257:526–527.

Moore CG, Francy DB, Eliason DA, Monath TP. 1988. Aedes albopictus in the United States: rapid spread of a potential disease vector. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 4:35–61.

Moore CG, Mitchell CJ. 1997. Aedes albopictus in the United States: ten-year presence and public health implications. Emerging Infectious Diseases 3:329–334.

O'Meara GF. 1997. The Asian tiger mosquito in Florida. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. No longer online.

Sprenger D, Wuithiranyagool T. 1986. The discovery and distribution of Aedes albopictus in Harris County, Texas. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 2:217–219.