The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

Applesnails are larger than most freshwater snails and can be separated from other freshwater species by their oval shell which has the umbilicus (the axially aligned, hollow, cone-shaped space within the whorls of a coiled mollusc shell) of the shell perforated or broadly open. There are four species of Pomacea in Florida, one of which is native and considered beneficial (Capinera and White 2011).

Species Found in Florida

Of the four species of applesnails in Florida, only the Florida applesnail is a native species, while the other three species are introduced. All are tropical/subtropical species in the genus Pomacea, and are not known to withstand water temperatures below 10°C (50°F) (FFWCC 2006).

Pomacea paludosa (Say, 1829), the Florida applesnail, occurs throughout peninsular Florida (Thompson 1984). Based on fossil finds, it is a native snail that has existed in Florida since the Pliocene. It is also native to Cuba and Hispaniola (FFWCC 2006). Collections have been made in Alabama, Georgia, Hawaii, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and South Carolina (USGS 2006). It is the principal food of the Everglades kite, Rostrhamus sociabilis plumbeus Ridgway, and should be considered beneficial. It cannot survive low winter temperatures that occur in the northern tier of Florida counties and northward except where the water is artificially heated by industrial wastewater or in warm springs. It occurs as far west as the Choctawhatchee River. It is easily distinguished from other applesnails in Florida by the low, strongly rounded shell spike, and measures about 40–70 mm (1 ½-2 ¾ in) (Capinera and White 2011).

Credit: Bill Frank

Pomacea maculata (Perry, 1810), the island applesnail, is the most common introduced species. This species was originally thought to be the channeled applesnail. Pomacea maculata was probably released in southern Florida in the early 1980s by persons with the tropical pet industry, and rapidly expanded throughout the state. Pomacea maculata is now found in Alabama, Georgia, Hawaii, Louisiana, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Texas. Introductions have occurred in Arizona, California, and Hawaii. (FFWCC 2006; USGS 2009b).

Credit: Bill Frank

Credit: Barbara Claiborne

Pomacea diffusa Blume, 1957, the spike-topped applesnail, is a Brazilian species that was introduced into southern Florida, probably in the 1950s. This species has a lower tolerance for cold water than the Florida applesnail and is established in Broward, Miami-Dade, Monroe and Palm Beach counties. It is also present in parts of central and north-central Florida. Collections have been made in Alabama and Mississippi (FFWCC 2006, USGS 2009a). It is marketed as an aquarium species under the name "golden applesnail." However, commercial varieties have been bred for the aquarium trade, including the "albino mystery snail." These aquarium snails are sometimes dumped into isolated bodies of water and have been recovered as far north as Alachua County, Florida (Thompson 1984). They feed mostly on decaying vegetation. This snail bears deep grooves between the shell whorls and is 40–60 mm high (1 ½-2 1/3 in) (Capinera and White 2011).

Credit: Bill Frank

Credit: Bill Frank

Pomacea haustrum (Reeve, 1856), the titan applesnail, is rare and is found only in southeastern Florida (FFWCC 2006; USGS 2007). This species lays green egg masses.

Credit: Luis Ruiz Berti

Credit: Bill Frank

Identification of Applesnails of Florida

Identification based on shell shape is very difficult. A much more complete key for all the freshwater snails of Florida is available online through the Florida Museum of Natural History at http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/malacology/fl-snail/snails1.htm.

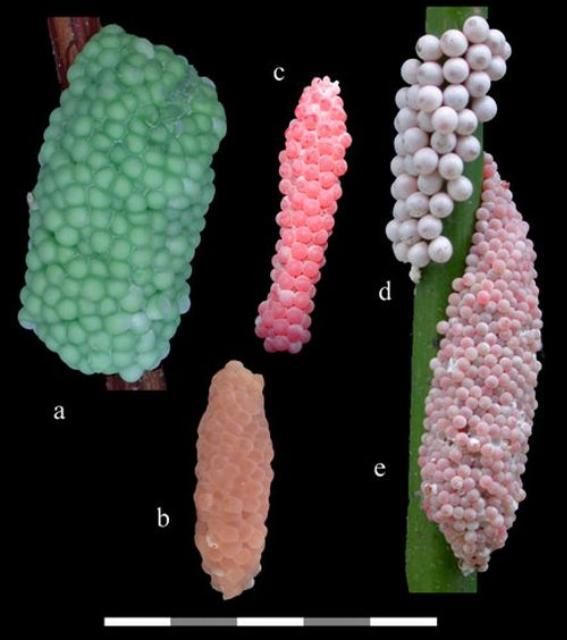

In applesnails, the spire of the shell can be conspicuous, but is much less than the height of the aperture. Applesnails lay grape-like clusters of white, green, or pink to red eggs on solid objects above the water line, and this is the quickest way to determine if applesnails are present.

Economic Importance of Invasive Species

The introduced island applesnail primarily eats rooted aquatic vegetation, while the native Florida applesnail feeds heavily on periphyton, a complex mixture of algae, cyanobacteria, heterotrophic microbes, and detritus attached to submerged surfaces in most aquatic ecosystems.

Mating and egg laying for both island and Florida applesnails start in March and can continue through October. The females emerge from the water, usually at night, to lay white or bright pink egg masses on stable substrates such as tree trunks, pilings, seawalls, or even plant stems. If adverse conditions occur, applesnails can burrow into sediments, seal the entrance to their shells with the operculum, and remain in this condition for several months. The other applesnails found in Florida seem not to be spreading or causing injury.

Credit: Bill Frank

However, it is the channeled applesnail, Pomacea canaliculata (Lamarck 1828), that causes concern to farmers. The channeled applesnail has caused significant damage to rice and taro crops in the Pacific islands and in southeastern Asia. Fortunately, this species has not been documented from Florida. It has been reported from California and Hawaii (USGS 2010). Although, the USGS map (2010) shows it in northeastern Florida, recent molecular data proved that this population was not Pomacea canaliculata (Capinera and White 2011).

Both the island and channeled applesnails are potential threats to Florida's aquatic ecosystems. It is not known whether these two species have similar feeding preferences (FFWCC 2006).

Credit: Jeffrey Lotz, DPI

Credit: Jeffrey Lotz, DPI

Management

While elimination of applesnails by chemical means has been attempted, no effective chemical recommendation has been developed. The most effective management methods are hand or mechanical removal of snails and egg masses. In Florida, some of the natural predators of applesnails include limpkins, Everglades (snail) kites, raccoons, turtles and alligators. It is also believed that redear sunfish and certain ducks will consume smaller immature snails (FFWCC 2006).

You can scrape off the egg masses and allow them to fall into the water since inundated eggs will not hatch. However, only pink egg masses should be scraped or removed. Egg masses with large, white eggs were laid by the native Florida applesnail and should be left undisturbed, as they do not pose a threat and are the principal food of the Everglades kite. Never release applesnails from aquaria into the wild (FFWCC 2006).

Credit: Rawlings et al.

Effective 5 April 2006, USDA-APHIS requires permits for importation or interstate shipment of all marine and freshwater snails. Permits are not being issued for members of the genus Pomacea, with the exception of the spike-topped applesnail, Pomacea diffusa (FFWCC 2006). To ship any of these species without a permit is a violation of United States federal law.

Selected References

Capinera JL, White J. (July 2011). Terrestrial snails affecting plants in Florida. Featured Creatures.

Estebenet AL, Cazzaniga NJ. 1992. Growth and demography of Pomacea canaliculata (Gastropoda: Ampullariidae) under laboratory conditions. Malacological Review 25: 1–12.

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FFWCC). (2006). Non-native applesnails in Florida.

Ghesquiere S. (2011). Apple snails.

Stange LA. 1998. The Applesnails of Florida (Gastropoda: Prosobranchia: Pilidae). FDACS-DPI. Entomology Circular 388. 2 pp.

Thompson FG. 1997. Pomacea canaliculata (Lamaarck 1822) (Gastropoda, Prosobranchia, Pilidae): A freshwater snail introduced into Florida, U.S.A. Malacological Review 30: 91.

Thompson FG. (2004). An Identification Manual for the Freshwater Snails of Florida. Florida Museum of Natural History.

USGS. (April 2006). Pomacea paludosa (Say 1829). Nonindigenous Aquatic Species.

USGS. (August 2007). (Reeve 1858). Nonindigenous Aquatic Species.

USGS. (August 2009a). Blume 1957. Nonindigenous Aquatic Species.

USGS. (October 2009b). Pomacea insularum Blume 1957. Nonindigenous Aquatic Species.

USGS. (January 2010). Pomacea canaliculata (Lamarck 1819). Nonindigenous Aquatic Species.

Winner BA. 1991. A Field Guide to Molluscan Spawn, II. Privately published, North Palm Beach. 94 p.