The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

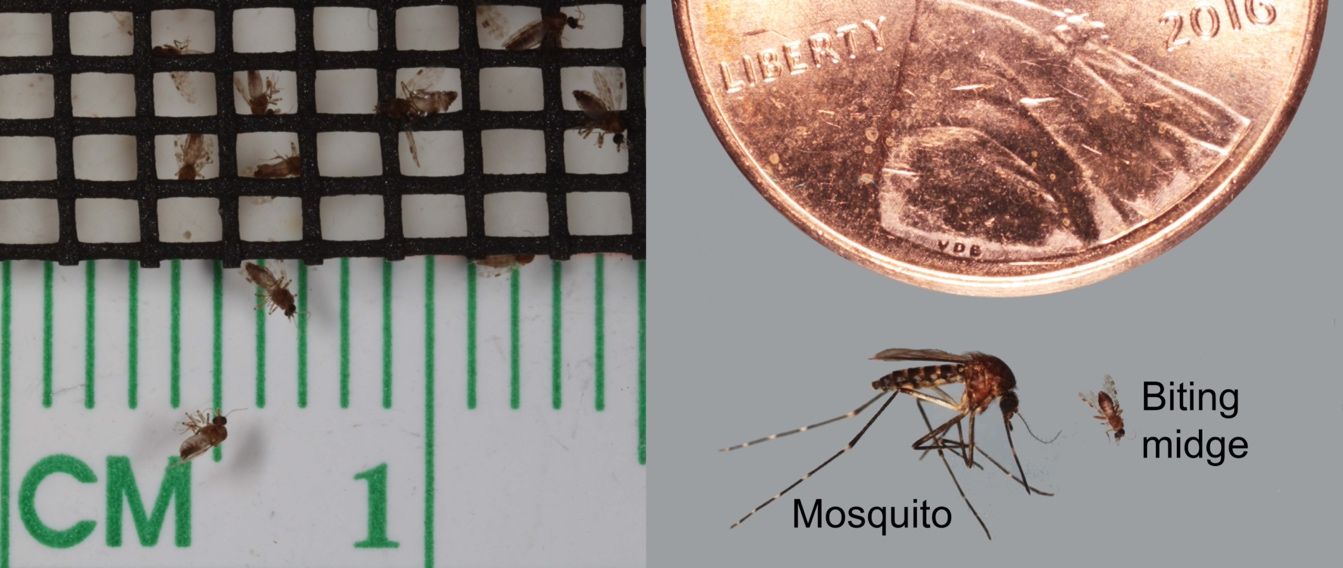

Biting midges (also known as no-see-ums, sand flies, or sand gnats) are tiny bloodsucking flies represented by only a few of the many genera in the family Ceratopogonidae. Biting midges are extremely small insects (Figure 1), and many species are less than one twenty-fourth of an inch (about 1 mm [0.04 in]). Biting midges are important for several reasons. In the United States, especially in coastal areas, these biting insects are often abundant and persistent pests of campers, beachgoers, fishers, and anyone desiring to enjoy the outdoors. Biting midges are also important as vectors (transmitters) of deadly and debilitating pathogens that affect wild and domesticated animals, especially livestock and game animals. Biting midges can even transmit pathogens that affect humans in many parts of the world, especially in South America and Africa.

Credit: Nathan Burkett-Cadena, UF/IFAS

Diversity and Distribution

Biting midges belong to the family Ceratopogonidae in the order Diptera (true flies). Although some genera within this family are known to bite and suck blood, the majority do not bite. The most diverse and widespread genus of biting midges is the genus Culicoides, which includes around 1,350 species worldwide (Borkent and Dominiak 2022). In the USA there are approximately 170 species of Culicoides (Borkent and Grogan 2009), of which around 50 occur in Florida (Blosser et al. 2024). In addition to Culicoides, a few species from other genera within the family Ceratopogonidae are also blood-feeders, including Leptoconops (in the subtropics and tropics), Forcipomyia subgenus Lasiohelea (in tropical rain forests), and two species of Austroconops (Western Australia).

In Florida, biting midge diversity is greatest in the northern half of the state. Numerous species of biting midges use water-filled treeholes as their larval habitat, and the trees that have these treeholes are much more common in the temperate hardwood forest of the Florida Panhandle and north-central Florida (Alachua County, for example). In south Florida, hardwood forests and trees with treeholes are less common, so treehole-adapted species are uncommon or absent. Several biting midge species are considered coastal pests and utilize marshes, swamps, and mangroves of coastal Florida as larval habitats. These coastal species can reach incredible densities and be so pestiferous that they drive even the most stout-hearted nature lovers indoors. Other biting midge species are adapted to the prairies of the south Florida interior and develop in low-lying sunny grasslands and marshes.

Description

Adults

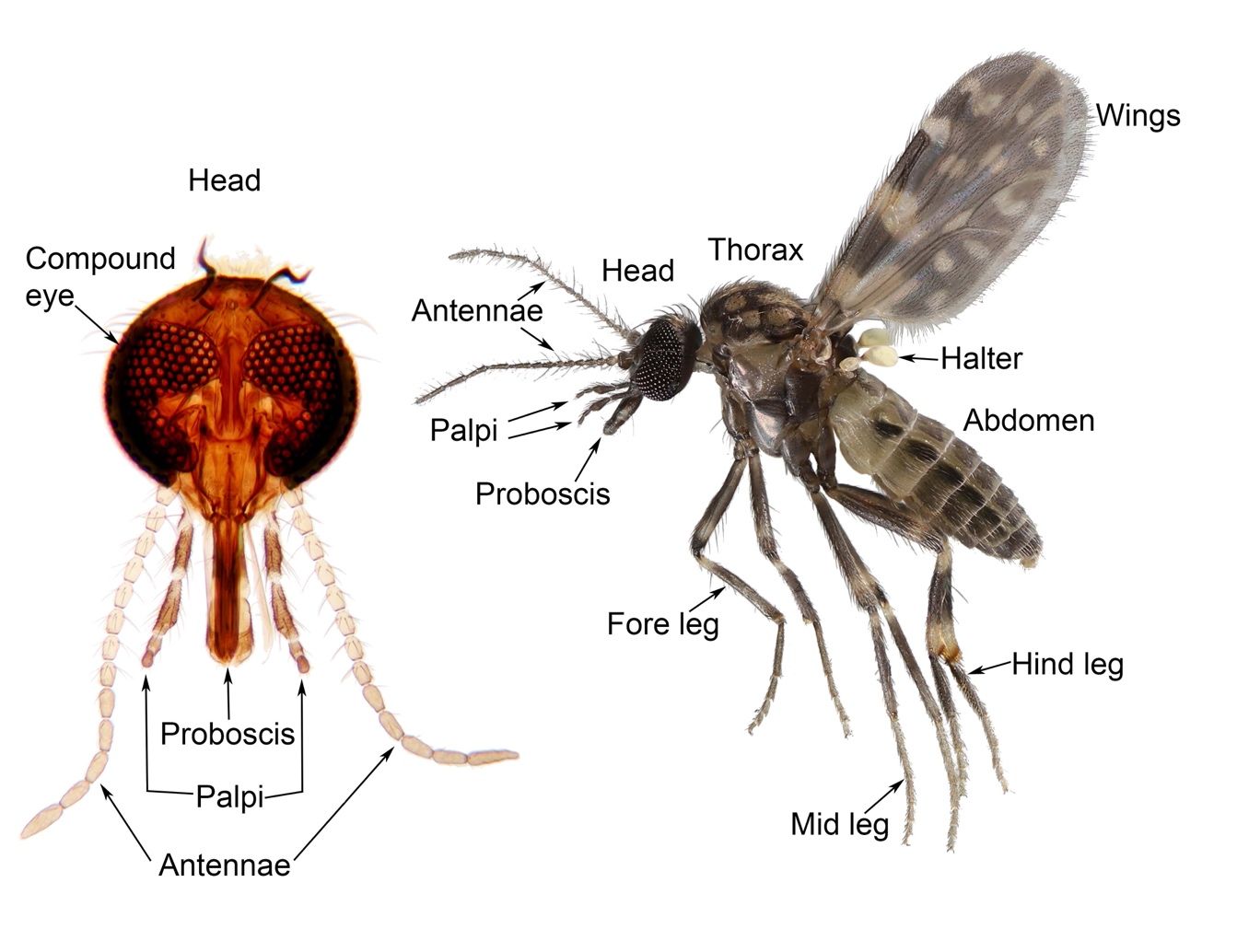

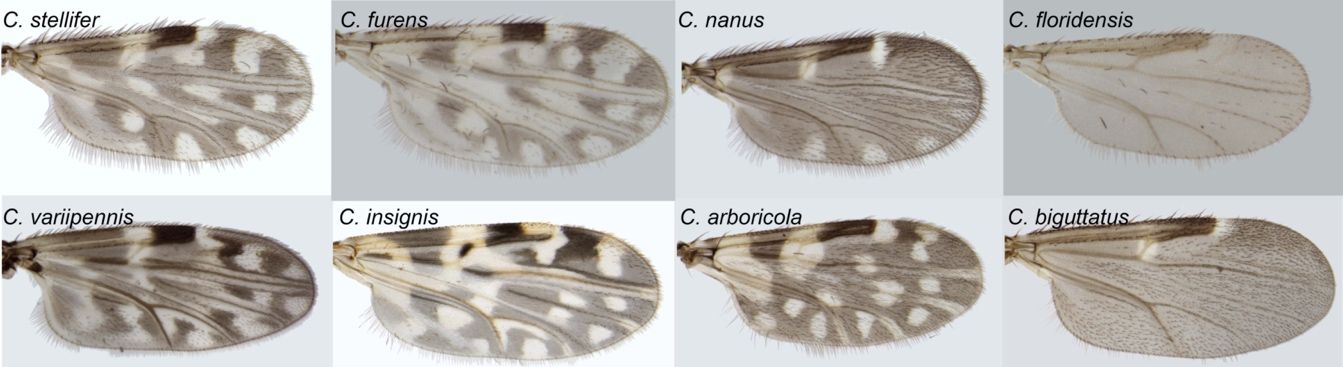

Adult biting midges (Figure 2) are tiny, usually 1.0 mm to 2.0 mm (0.04 to 0.08 in) long (Figure 1). Of the 50 or so species that occur in Florida, the average length is about 1.5 mm (0.06 in). The mouthparts of female biting midges are specialized for piercing the flesh of vertebrate animals and sucking their blood (Figure 2). Their mouthparts are elongated to form a proboscis, which consists of multiple elements, including mandibles, which are used for cutting flesh, and a hypopharynx, which transports saliva and host blood. Male biting midges have mouthparts that generally resemble those of the female but are not adapted for piercing skin. The palpi are five-segmented appendages of the mouthparts that possess a sensory organ (on the third segment) used to locate host animals. The antennae of biting midges have 15 segments. The basal 10 segments are usually short, while the apical five segments are much longer. Adult biting midges, like other Diptera, have two wings. The wings have veins, which give the wing its rigidity, and cells made of membranous exoskeleton. The wings of most biting midge species are patterned with dark and pale spots characteristic of the species (Figure 3). These “wing patterns” are extremely important in identifying biting midges to species. The halteres are the remnants of hind wings, used as flight stabilizers. Biting midges have three pairs of legs, and each leg has five segments (coxa, trochanter, femur, tibia, tarsus) that terminate in robust claws. The abdomen of a biting midge is segmented and terminates in the copulatory (mating) appendages. In females, the copulatory appendages are barely visible, while in males, the copulatory appendages appear as grasping structures.

Credit: Nathan Burkett-Cadena, UF/IFAS

Credit: Nathan Burkett-Cadena, UF/IFAS

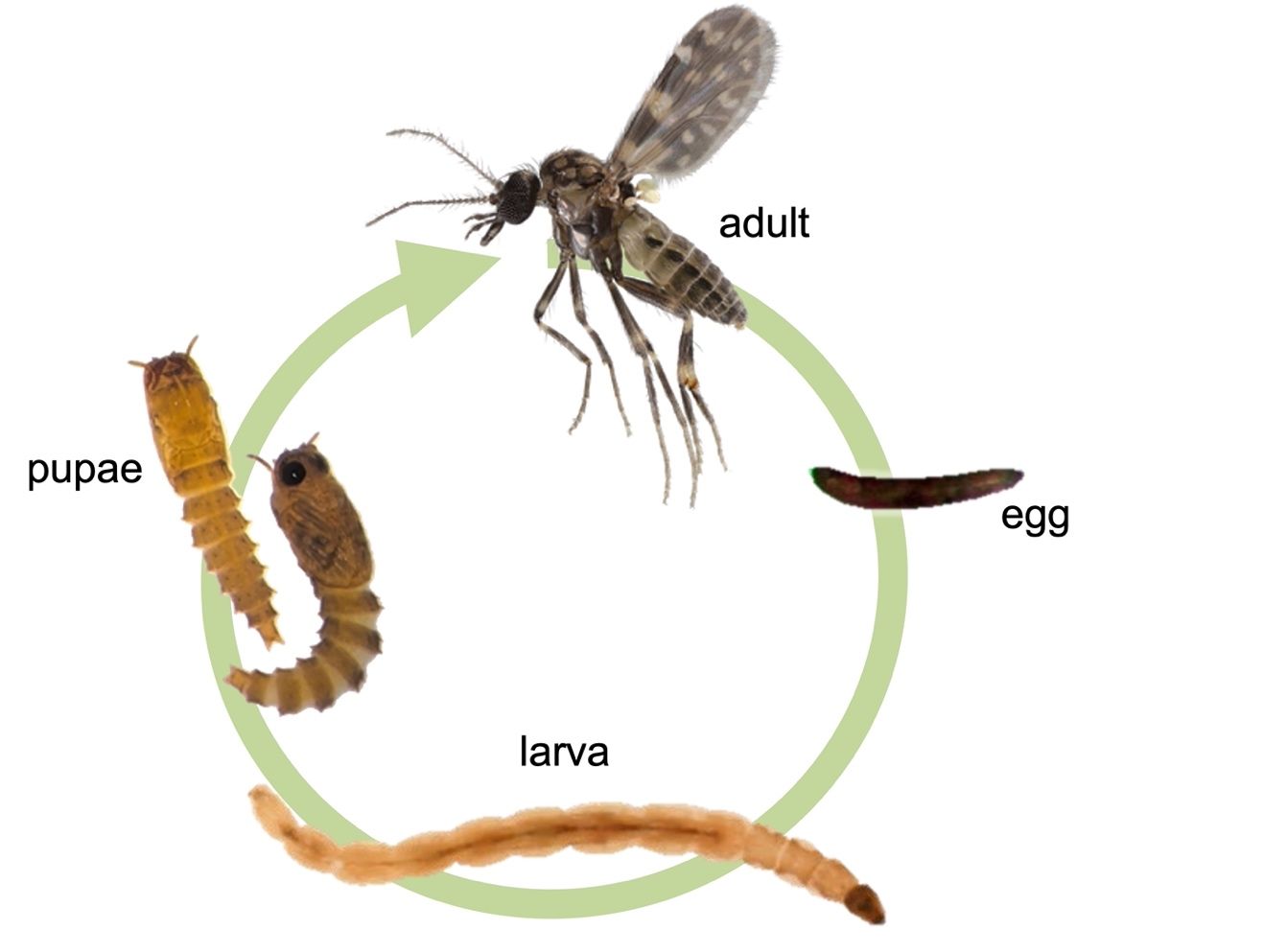

Eggs

Eggs of biting midges are extremely small (about 0.25 mm or 0.01 inch long) and crescent shaped (Figure 4). The eggs are white when newly laid but then darken to brown as they mature (Blanton and Wirth 1979).

Credit: Nathan Burkett-Cadena, UF/IFAS

Larvae

Biting midge larvae are typically long and very slender, generally resembling a tiny worm (Figure 4). Like adults, they are extremely small (2 mm to 5 mm [0.08 to 0.2 in] long when mature). The head is typically brown or tan and much darker than the rest of the body (Figure 4), which is usually milky or translucent. Segments of the thorax (three segments) and abdomen (nine segments) are roughly cylindrical, about twice as long as they are wide, and similar in size. At the tail end of the body are four pairs of setae (bristles) that are used for locomotion and a pair of narrow papillae (fingerlike projections) that may be visible or retracted into the rectum. Larvae generally lack spiracles and respire through their exoskeletons. The mouthparts of biting midge larvae are composed of several elements that are used for scraping, chewing, seizing prey, and/or filtering food particles. The shape of the mandibles and other mouthparts, can be important in identifying biting midge larvae to species (Blanton and Wirth 1979; Mullen and Murphree 2019).

Pupae

Biting midge pupae are small (2 mm to 4 mm [0.1 to 0.2 in]) and elongate with a mobile and flexible body. The head and thorax are fused into a “cephalothorax,” which bears the eyes and respiratory organs, called “horns,” that arise near the dorsal anterior portion of the body (Figure 4). The abdomen is distinctly segmented and typically spiky or pointed. Pupae move with a distinctive swaying motion of the abdomen. When the pupa is fully mature, features of the adult biting midge, such as the wings, legs, eyes, and mouthparts, can be seen through its exoskeleton.

Life Cycle and Ecology

Adults

Like other flies, biting midges are holometabolous, which means that they pass through four complete life-stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult (Figure 4). As adults, biting midges of many species fly relatively long distances (2 km or about 1.2 miles) for insects that measure only a few millimeters. For instance, Culicoides variipennis females have been found to fly up to four kilometers (about 2.5 miles) (Lillie et al. 1981). Other species, like Culicoides mohave, have been found to fly up to six kilometers (3.7 miles) in California (Brenner et al. 1984).

It is very difficult to study the lifespan of a tiny insect in the wild, so our understanding of how long biting midges live is mainly based on the results of laboratory studies. For example, Culicoides obsoletus adults survived more than 90 days in the laboratory (Barcelo and Miranda 2021). In general, very little is known about how long adult biting midges live in nature, but adults of most species probably live at least one month. Adult male and female biting midges feed on nectar as a source of carbohydrates (Mullen and Murphee 2019). During their lifespan, females of most species feed on vertebrate blood to obtain nutrients for egg development. Some species can produce at least one batch of eggs without taking a bloodmeal. As a group, biting midges bite all four classes of terrestrial vertebrates (amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals). Most species that have been studied bite primarily mammals, but other species bite birds, and a few species bite amphibians and/or reptiles (Mullen and Murphree 2019). One species, Culicoides testudinalis Wirth and Hubert, mainly bites turtles (Jamnback 1965).

Most biting midge species generally bite during dusk, night, or morning (Kettle 1962). However, much variation in the time of day that species bite is recognized. During cold weather, for example, and in coastal areas, many biting midge species will bite in broad daylight. Culicoides arboricola Root & Hoffman, Culicoides edeni Wirth & Blanton, and Culicoides knowltoni mostly bite their host animals (birds) within one hour after sunset (Garvin and Greiner 2003). On the other hand, Culicoides tissoti, a species that utilizes freshwater springs as larval development sites, bites aggressively in the daytime (Blanton and Wirth 1979).

Eggs

Generally, females lay eggs within a week after taking a bloodmeal, with the number of eggs per batch varying between species. For example, egg batches of Culicoides sonorensis can contain up to 179 eggs (Jones 1967), while Culicoides variipennis have been shown to produce up to 243 eggs per batch and up to 1,143 eggs throughout their lifespan (Jones 1967). Culicoides furens can lay 50 to 110 eggs per clutch, and Culicoides mississippiensis Hoffman 25 to 50 eggs per clutch. Eggs are generally deposited on moist substrates (Blanton and Wirth 1979). Typically, the eggs hatch within a few days of being laid, for example, between two to five days for Culicoides sonorensis (Jones 1967); two to four days for Culicoides furens; and five to seven days for Culicoides barbosai (Linley 1966). While eggs of biting midges cannot survive drying, the eggs of many species can remain dormant for months waiting for appropriate hatching signals (e.g., temperature, moisture).

Larvae

Biting midge larvae pass through four stages, called instars, which each last a few days. The growth and development of biting midge larvae is rapid and generally is completed within two weeks. For example, Culicoides variipennis can develop from egg to adult within 16 days in laboratory conditions. However, some species can remain in the larval stage for long periods—up to one year—especially when conditions are not optimal, for example, due to low food availability or low temperatures.

As a group, larvae of biting midges can develop in a wide array of habitats where they have access to water, air, and food (Blanton and Wirth 1979), including the edges of streams, marshes, ponds, puddles, and treeholes (Table 1). Each species, however, is usually found in just one or two types of larval habitats. The species that develop in wet treeholes, for example, do not develop in marshes or ponds. Some species, such as Culicoides loughnani, have very specific larval habitats, like rotting cactus. Larvae of biting midges are not fully aquatic but do require substantial moisture for their development. Biting midge larvae feed on microscopic organisms like other insects, nematodes, tardigrades, and bacteria (Hribar and Mullen 1991).

Table 1. Larval habitats of some biting midge species in Florida.

Pupae

A fully developed larva transforms into a pupa, the stage in which a holometabolous insect undergoes dramatic morphological changes before emerging as a flying adult capable of feeding and reproducing. Because they do not feed or move long distances, the pupae of biting midges are generally found in the same habitats as the larvae. The pupal stage is sometimes as short as 1.5 days, but can be much longer, especially when substrate moisture or temperatures are low (Vaughan and Turner 1987).

Medical and Veterinary Significance

Dozens of species of biting midges are important as significant biting pests and transmitters of human and animal pathogens around the world. Most people are probably familiar with the annoying and persistent nuisance “no-see-ums” that bite and can reach incredible densities in coastal areas. Reactions to bites generally consist of localized stinging or burning sensations with defined red areas surrounding bite sites. While discomfort usually lasts for minutes to hours, individuals who are hypersensitive to bites may itch for two to three days (Mullen and Murphee 2019). In some areas of Sub-Saharan Africa and the American tropics, biting midges are known to transmit dangerous human pathogens including filarial worms in the genus Mansonella, which cause mansonellosis, and the potentially deadly Oropouche virus (OROV) (Downes et al. 2014). Mansonellosis presents with mild fever, dermatitis, and skin lesions (Lima et al. 2016; Simonsen et al. 2014). Biting midges are a cause of concern for livestock farmers because they transmit viruses that can affect horses, cattle, sheep, and deer. Additionally, biting midge bites can trigger “sweet itch,” a form of allergic dermatitis often seen in horses (Anderson et al. 1993).

Culicoides paraensis is one of the principal vectors (transmitters) of Oropouche virus (OROV) in South America and the Caribbean (Dixon et al. 1981; Pinheiro et al. 1981a). While antibodies to OROV have been detected in monkeys and wild birds, sloths are the only known natural virus reservoir for OROV (Pinheiro et al. 1981b). Recently, OROV has spread beyond South America to locations like Haiti, Cuba, and Dominican Republic where sloths do not occur. Scientists speculate that the expanding strains of OROV are mutated forms of the virus, and the mutation allows the virus to use humans as hosts and some mosquito species as vectors (Scachetti et al. 2024). Oropouche virus causes a potentially deadly illness in humans known as Oropouche fever. The most common symptoms are fever, chills, headaches, muscle and joint aches, malaise, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and light sensitivity. Although the illness is generally mild, more severe symptoms such as spontaneous bleeding or meningitis may occur, particularly in immunocompromised individuals and children (Sakkas et al. 2018).

Biting midges in the genus Culicoides transmit hemorrhagic disease viruses, such as bluetongue virus (BTV) and epizootic hemorrhagic disease virus (EHDV) to wild and domestic ruminants like sheep, cattle, and deer. These lead to substantial losses in productivity and animal deaths each year and cost ranchers and farmers millions of dollars. The diseases caused by BTV and EHDV are clinically indistinguishable from one another, with symptoms in animals including swelling and bluish discoloration of the tongue, hoof inflammation, hemorrhaging, and death (Mullen and Murphee 2019; McGregor et al. 2022). In the United States, Culicoides sonorensis and Culicoides insignis are the confirmed Culicoides vectors of BTV and EHDV (McGregor et al. 2022). More information on Bluetongue can be found in the Bluetongue Ask IFAS publication available on https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu.

African horse sickness virus (AHSV) is also transmitted by biting midges in genus Culicoides (Mellor and Hamblin 2004). The disease caused by AHSV is endemic to Sub-Saharan Africa, but outbreaks of AHS have also occurred in North Africa, the Middle East, the Arabian Peninsula, Southwest Asia, and the Mediterranean region (Sanchez-Vizcaino et al. 2014). African horse sickness is considered the most economically significant equine disease worldwide and affects horses, mules, and donkeys (Dennis et al. 2019). Three clinical forms of the disease, pulmonary, cardiac, and horse sickness fever, as well as a mixed form, are recognized. These range in symptom severity and fatality rates (Burrage and Laegreid 1994). The mildest form of AHS, horse sickness fever, is generally not fatal. Symptoms of horse sickness fever include low-grade fever, anorexia, depression, and congestion (Faber et al. 2022). The pulmonary-cardiac form of AHS is the most common and lethal form, with a mortality rate of 70% (Dennis et al. 2019).

Lastly, Schmallenberg virus (SBV), first detected in Europe in 2011, is transmitted by Culicoides species to ruminants such as cattle, goats, and sheep (Rasmussen et al. 2012; Balengheim et al. 2014). Animals infected with SBV generally exhibit mild symptoms like fever, anorexia, and diarrhea (Davies et al. 2012). Most importantly, milk production of infected animals can be reduced by up to 50%, resulting in high economic losses for dairy farmers (Hoffmann et al. 2011; Muskens et al. 2012).

Management and Prevention

Historically, control strategies for biting midges have focused on nuisance species (Carpenter et al. 2008). However, since biting midges are important vectors of animal and human pathogens, interest in controlling biting midges and their impacts has increased in recent years. Strategies for controlling midges and preventing the diseases caused by viruses transmitted by biting midges include vaccination, adulticide sprays, biological and cultural control, and habitat modification.

Vaccination

Vaccination is often considered the most effective method of preventing diseases caused by viruses transmitted by biting midges (Harrup et al. 2016). However, the development of a vaccine requires extensive research, and vaccines are sometimes not used due to financial, logistical, or trade constraints (Harrup et al. 2016). The use of vaccines against biting-midge-transmitted viruses can also have some additional challenges. For instance, EHDV and BTV vaccines generally protect animals against only one or a few of the many known serotypes of these diseases. In some states in the USA, BTV vaccines are available to protect sheep against BTV serotypes 10, 11, and 17. For EHD, however, no licensed vaccines are available in the USA, though experimental vaccines against EHDV-2 and EHDV-6 are available. Vaccinating some animals can also be especially challenging. Vaccination of deer, for example, may not be practical for wild, semi-wild, or free-ranging animals (Orange et al. 2021).

Adulticide Sprays

Vector control techniques worldwide rely largely on the use of chemical insecticides to kill or deter vectors (Van Den Berg et al. 2021). Various organophosphates and pyrethroids applied as ultra-low-volume (ULV) sprays have been used for the reduction of nuisance biting midges (Carpenter et al. 2008). Pyrethrins and synthetic pyrethroids are the predominant insecticide class for the control of blood-feeding dipterans such as mosquitoes and biting midges (Walters et al. 2009). The pyrethroid permethrin, for example, is widely used for mosquito control in the United States (EPA 2024) and is the main insecticide used against the biting midges that transmit BTV and EHDV in Florida (Harmon et al. 2020). The popularity of pyrethroids is in part associated with their high insecticidal potency and relative safety for mammals (van Balen et al. 2012).

In Florida, researchers have tested the efficacy of ULV applications with adulticides containing organophosphates (malathion, naled) and the pyrethroid resmethrin, against the coastal pest Culicoides furens (Linley et al. 1987; Linley et al. 1988; Linley and Jordan 1992). Naled was found to be the most effective ULV spray, achieving 90% mortality at distances up to 106 m, compared to 36 m for malathion and 25 m for resmethrin.

More recently, ULV applications with Permanone 30-30 (30% permethrin, 30% piperonyl butoxide) have resulted in complete mortality in field-collected adult biting midges Culicoides furens from Florida (Cooper et al. 2025). Additionally, applications of Talstar®, a 7.9% bifenthrin barrier spray product, at the maximum label rate reduced the numbers of Culicoides furens (Lloyd et al. 2021).

Other Control Strategies

Alternative control strategies, including biological and cultural control approaches, are commonly used on livestock farms to deter or eliminate biting midges, although their effectiveness remains insufficiently validated. Installing screens on windows and doors may reduce the number of biting midges entering animal enclosures (Harrup et al. 2016). Pyrethroid-impregnated ear tags have also been designed to repel and kill biting midges and other blood-sucking flies (Harrup et al. 2016). Keeping animals indoors from dusk until dawn may offer protection from biting midges (Carpenter et al. 2008; Baylis et al. 2010). Unfortunately, this approach is challenging for large herds or nontame animals like white-tailed deer.

Habitat modification is a method of altering and/or eliminating habitats where the larvae and pupae of biting midges develop (Harrup et al. 2016). The larvae and pupae of biting midges cannot survive desiccation (drying out) (McDermott and Lysyk 2020). Therefore, improving water drainage may reduce the number of larvae present in an area. A study in California tested the impact of removing a wastewater pond complex known to support a large population of Culicoides sonorensis. However, no difference on the adult Culicoides sonorensis population was found after removing the ponds, despite the elimination of what is thought to be the main developmental site for this species (Mayo et al. 2014). This study highlights the limited understanding of the developmental habitats of biting midges, and the challenges of habitat modification practices for the control of biting midges. The practicality of habitat modification to control biting midges may be limited by the implementation cost and the existence of regulatory issues such as the destruction of wetlands in the United States and the European Union (Pfannenstiel et al. 2015).

Human Protection Against Biting Midges

Window and door screens can be used to prevent the entry of biting midges into indoor areas. The opening size of the screen is an important factor to consider, as regular window screens do not exclude biting midges from indoor areas (Figure 1). The openings of biting midge (no-see-um) screen are small enough to exclude biting midges, but biting midge screen is not typically used as a window or door screen.

DEET-based repellents commonly used to protect humans from mosquitoes are also the main repellent used to repel biting midges (Harrup et al. 2016). However, other products, including those made with essential oils, have gained popularity. For example, the essential oil from Melaleuca ericifolia has been shown to achieve 95% repelling efficacy against Culicoides ornatus and Culicoides immaculatus up to three hours after application in field conditions in Australia (Greive et al. 2010). Essential oils have also been successful in repelling biting midges in laboratory experiments. For instance, essential oils from lemon eucalyptus Eucalyptus maculata var. citriodora were up to 100% repellent against Culicoides obsoletus, performing even better than DEET, which showed 75% repellency (Gonzalez et al. 2014).

Selected References

Anderson GS, Belton P, Kleider N. 1993. Hypersensitivity of horses in British Columbia to extracts of native and exotic species of Culicoides (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae). Journal of Medical Entomology 30 (4): 657–663. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/30.4.657

Balengheim T, Pages N, Goffredo M, Carpenter S, Augot D, Jacquier E, Talavera S, Monaco F, Depaquit J, Grillet C, Pujols J, Satta G, Kasbari M, Setier-Rio ML, Izzo F, Alkan C, Delécolle JC, Quaglia M, Charrel R, Polci A, Bréard E, Federici V, Cêtre-Sossah C, Garros C. 2014. The emergence of Schmallenberg virus across Culicoides communities and ecosystems in Europe. Preventative Veterinary Medicine. 116:360–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2014.03.007

Barceló C, Miranda MA. 2021. Development and lifespan of Culicoides obsoletus s.s. (Meigen) and other livestock-associated species reared at different temperatures under laboratory conditions. Medical Veterinary Entomology 35 (2): 187–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/mve.12487

Blanton FS, Wirth WW. 1979. The sand flies (Culicoides) of Florida (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae). Arthropods of Florida and Neighboring Land Areas; Volume 10. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. Gainesville, FL. 204 pp.

Blosser EM, McGregor BL, Burkett-Cadena ND. 2024. A photographic key to the adult female biting midges (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae: Culicoides) of Florida, USA. Zootaxa 5433 (2): 151–182. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.5433.2.1

Borkent A, Dominiak P, Daz F. 2022. An update and errata for the catalog of the biting midges of the world (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae). Zootaxa 5120 (1): 53–64. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.5120.1.3

Borkent A, Grogan WL. 2009. Catalog of the New World biting midges North of Mexico (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae). Zootaxa 2273 (2273): 1–48. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2273.1.1

Brenner RJ, Wargo MJ, Stains GS, Mulla MS. 1984. The dispersal of Culicoides mohave (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) in the desert of Southern California. Mosquito News 44:343–350.

Burrage T, Laegreid W. 1994. African horse sickness: pathogenesis and immunity. Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Disease 17:275–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-9571(94)90047-7

Carpenter S, Mellor PS, Torr SJ. 2008. Control techniques for Culicoides biting midges and their application in the U.K. and northwestern Palaearctic. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 22 (3): 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2915.2008.00743.x

Cooper VM, Buckner EA, Jiang Y, Burkett-Cadena ND. 2025. Laboratory and field assays indicate that a widespread no-see-um, Culicoides furens (Poey) is susceptible to permethrin. Scientific Reports, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-025-89520-0

Davies I, Vellema P, Roger P. 2012. Schmallenberg virus—an emerging novel pathogen. In Practice 34:598. https://doi.org/10.1136/inp.e7372

Dennis SJ, Meyers AE, Hitzeroth II, Rybicki EP. 2019. African horse sickness: A review of current understanding and vaccine development. Viruses 11 (9): 844. https://doi.org/10.3390/v11090844

Dixon KE, Travassos da Rosa AP, Travassos da Rosa JF, Llewellyn CH. 1981. Oropouche virus. II. Epidemiological observations during an epidemic in Santarém, Pará, Brazil in 1975. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 30:161–164.

Downes BL, Jacobsen KH. 2010. A systematic review of the epidemiology of mansonelliasis. African Journal of Infectious Diseases 4 (1): 7–14. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajid.v4i1.55085

Environmental Protection Agency. 2024. Permethrin, resmethrin, d-phenothrin (Sumithrin): Synthetic pyrethroids for mosquito control. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/mosquitocontrol/permethrin-resmethrin-d-phenothrin-sumithrinr-synthetic-pyrethroids-mosquito. [Accessed 5 October 2024]

Faber E, Tshilwane SI, Van Kleef M, Pretorius A. 2022. Apoptosis versus survival of African horse sickness virus serotype 4-infected horse peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Virus Research 307:198609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2021.198609

Garvin MC, Greiner EC. 2003. Ecology of Culicoides (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) in southcentral Florida and experimental Culicoides vectors of the avian hematozoan Haemoproteus danilewskyi Kruse. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 39 (1): 170–178. https://doi.org/10.7589/0090-3558-39.1.170

González M, Venter GJ, López S, Iturrondobeitia JC, Goldarazena A. 2014. Laboratory and field evaluations of chemical and plant‐derived potential repellents against Culicoides biting midges in northern Spain. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 28 (4): 421–431. https://doi.org/10.1111/mve.12081

Greive KA, Staton JA, Miller PF, Peters BA, Oppenheim VMJ. 2010. Development of Melaleuca oils as effective natural-based personal insect repellents. Australian Journal of Entomology 49:40–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-6055.2009.00736.x

Harmon LE, Sayler KA, Burkett-Cadena ND, Wisely SM, Weeks ENI. 2020. Management of plant and arthropod pests by deer farmers in Florida. Journal of Integrated Pest Management 11 (1): 12. https://doi.org/10.1093/jipm/pmaa011

Harrup LE, Miranda MA, Carpenter S. 2016. Advances in control techniques for Culicoides and future prospects. Veterinaria Italiana 52 (3–4): 247–264. https://doi.org/10.12834/vetit.741.3602.3

Hoffmann B, Scheuch M, Höper D, Jungblut R, Holsteg M, Schirrmeier H, Eschbaumer M, Goller KV, Wernike K, Fischer M, Breithaupt A, Mettenleiter TC, Beer M. 2012. Novel orthobunyavirus in cattle, Europe, 2011. Emerging Infectious Diseases 18:469–472. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1803.111905

Hopken MW, Ryan BM, Huyvaert KP, Piaggio AJ. 2017. Picky eaters are rare: DNA-based blood meal analysis of Culicoides (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) species from the United States. Parasites and Vectors 10 (1): 169. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-017-2099-3

Howell PG. 1962. The isolation and identification of further antigenic types of African horse sickness virus. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research 29:139–149.

Hribar LJ, Mullen GR. 1991. Comparative morphology of the mouthparts of biting midge (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) larvae. Contributions of the American Entomological Institute 26:1–71

Jamnback, H. 1965. The Culicoides of New York State (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae). Vol 399. The University of the State of New York, Albany, New York, United States of America.

Jones HR. 1967. Some irradiation studies and related biological data for Culicoides variipennis (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 60 (4): 836–846.

Kettle DS. 1962. The bionomics and control of Culicoides and Leptoconops (Diptera, Ceratopogonidae = Heleidae). Annual Review of Entomology 7:401–418.

Lillie TH, Marquardt WC, Jones RH. 1981. The flight range of Culicoides variipennis (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae). The Canadian Entomologist 113 (5): 419–426.

Lima NF, Aybar CA, Juri MJ, Ferreira MU. 2016. Mansonella ozzardi: a neglected New World filarial nematode. Pathogens and Global Health 110 (3): 97–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/20477724.2016.1190544

Linley JR. 1966. The ovarian cycle in Culicoides barbosai Wirth & Blanton and C. furens (Poey) (Diptera, Ceratopogonidae). Bulletin of Entomological Research 57 (1): 1–17.

Linley JR, Jordan S. 1992. Effects of ultra-low volume and thermal fog malathion, scourge and naled applied against caged adult Culicoides furens and Culex quinquefasciatus in open and vegetated terrain. Journal of American Mosquito Control Association 8:69–76.

Linley JR, Parsons RE, Winner RA. 1987. Evaluation of naled applied as a thermal fog against Culicoides furens (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae). Journal of American Mosquito Control Association 3:387–391.

Linley JR, Parsons RE, Winner RA. 1988. Evaluation of ULV naled applied simultaneously against caged adult Aedes taeniorhynchus and Culicoides furens. Journal of American Mosquito Control Association 4:326–332.

Lloyd AM. 2021. Field evaluation of Talstar (bifenthrin) residential barrier treatments alone and in conjunction with Mosquito Magnet Liberty Plus traps in Cedar Key, Florida. Journal of Florida Mosquito Control Association 68 (1): 56–62. https://doi.org/10.32473/jfmca.v68i1.129100

Mayo CE, Osborne CJ, Mullens BA, Gerry AC, Gardner IA, Reisen WK, Barker CM, Maclachlan NJ. 2014. Seasonal variation and impact of waste-water lagoons as larval habitat on the population dynamics of Culicoides sonorensis (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) at two dairy farms in northern California. PLoS One 9(2). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089633

McDermott EG, Lysyk TJ. 2020. Sampling considerations for adult and immature Culicoides (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae). Journal of Insect Science 20 (6): 2. https://doi.org/10.1093/jisesa/ieaa025

McGregor BL, Shults PT, McDermott EG. 2022. A review of the vector status of North American Culicoides (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) for bluetongue virus, epizootic hemorrhagic disease virus, and other arboviruses of concern. Current Tropical Medicine Reports 9 (4): 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40475-022-00263-8

McVey DS, MacLachlan NJ. 2015. Vaccines for prevention of bluetongue and epizootic hemorrhagic disease in livestock: A North American perspective. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 15 (6): 385–396. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2014.1698

Mellor PS, Hamblin C. 2004. African horse sickness. Veterinary Research 35 (4): 445–466. https://doi.org/10.1051/vetres:2004021

Mullen GR, Murphree CS. 2019. Biting midges (Ceratopogonidae). In: Mullen G, Durden L, editors. Medical and Veterinary Entomology, 3rd Edition, Academic Press, London, United Kingdom, 213–236 pp.

Muskens J, Smolenaars AJ, van der Poel WH, Mars MH, van Wuijckhuise L, Holzhauer M. van Weering H, Kock P. 2012. Diarrhea and loss of production on Dutch dairy farms caused by the Schmallenberg virus. Tijdschr Diergeneeskd 137 (2): 112–115.

Orange JP, Dinh ETN, Goodfriend O, Citino SB, Wisely SM, Blackburn JK. 2021. Evidence of epizootic hemorrhagic disease virus and bluetongue virus exposure in nonnative ruminant species in northern Florida. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 51 (4): 745–751. https://doi.org/10.1638/2019-0174

Pfannenstiel RS, Mullens BA, Ruder MG, Zurek L, Cohnstaedt LW, Nayduch D. 2015. Management of North American Culicoides biting midges: Current knowledge and research needs. Vector Borne Zoonotic Diseases 15 (6): 374–384. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2014.1705

Pinheiro FP, Hoch AL, Gomes ML, Roberts DR. 1981a. Oropouche virus. IV. Laboratory transmission by Culicoides paraensis. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 30 (1): 172–176.

Pinheiro FP, Travassos da Rosa AP, Travassos da Rosa JF, Ishak R, Freitas RB, Gomes ML, LeDuc JW, Oliva OF. 1981b. Oropouche virus. I. A review of clinical, epidemiological, and ecological findings. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 30 (1): 149–160.

Rasmussen LD, Kristensen B, Kirkeby C, Rasmussen TB, Belsham GJ, Bødker R, Bøtner A. 2012. Culicoides as vectors of Schmallenberg virus. Emerging Infectious Diseases 18 (7): 1204–1206. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1807.120385

Sakkas H, Bozidis P, Franks A, Papadopoulou C. 2018. Oropouche fever: A review. Viruses 10 (4): 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/v10040175

Sánchez-Vizcaíno JM, Martínez-Avilés M, Sánchez-Matamoros A, Rodríguez-Prieto V. 2014. Emerging vector-borne diseases and the potential to prevent them spreading. CABI Reviews 9:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1079/PAVSNNR20149039

Scachetti GC, Forato J, Claro IM, Hua X, Salgado BB, Vieira A, Simeoni CL, Barbosa ARC, Rosa IL, de Souza GF, Fernandes LCN, de Sena ACH, Oliveira SC, Singh CML, de Lima ST, de Jesus R, Costa MA, Kato RB, Rocha JF, Santos LC, Rodrigues JT, Cunha MP, Sabino EC, Faria NR, Weaver SC, Romano CM, Lalwani P, Proença-Módena JL, de Souza WM. 2024. Reemergence of Oropouche virus between 2023 and 2024 in Brazil. Lancet Infectious Diseases PIIS1473309924006194. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00619-4

Simonsen PE, Fischer PU, Hoerauf A, Weil GJ. 2014. The filariasis. In: Farrar J, Hotez PJ, Junghanss T, Kang G, Lalloo D, White NJ, editors. Manson’s Tropical Diseases. 23rd edition, Saunders, London, United Kingdom, 737–765 pp.

Sloyer KE, Acevedo C, Wisely SM, Burkett-Cadena ND. 2023. Host associations of biting midges (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae: Culicoides) at deer farms in Florida, USA. Journal of Medical Entomology 60 (3): 518–526. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjad036

Van Den Berg H, Da Silva Bezerra HS, Al-Eryani S, Chanda E, Nagpal BN, Knox TB, Velayudhan R, Yadav RS. 2021. Recent trends in global insecticide use for disease vector control and potential implications for resistance management. Science Reports 11 (1): 23867. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03367-9

Vaughan JA, Turner EC Jr. 1987. Development of immature Culicoides variipennis (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) from Saltville, Virginia, at constant laboratory temperatures. Journal of Medical Entomology 24 (3): 390–395. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/24.3.390

Walters JK, Boswell LE, Green MK, Heumann MA, Karam LE, Morrissey BF, Waltz JE. 2009. Pyrethrin and pyrethroid illnesses in the Pacific northwest: a five-year review. Public Health Reports 124 (1): 149–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335490912400118