The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids, and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

The red-spotted purple, Limenitis arthemis astyanax (Fabricius), is a beautiful forest butterfly that is also commonly seen in wooded suburban areas. It is considered to be a Batesian mimic of the poisonous pipe vine swallowtail, Battus philenor (Linnaeus), with which it is sympatric.

The white admiral, Limenitis arthemis arthemis (Drury), is a more northern subspecies and is not mimetic. It is believed to benefit from its disruptive banded coloration for protection in the absence of a poisonous model (Platt and Brower 1968). The red-spotted purple interbreeds with the white admiral in the zone of overlap, and the hybrids are healthy and fertile (Scott 1986).

The red-spotted purple also interbreeds with the closely related, congeneric viceroy butterfly, Limenitis archippus (Cramer), both in the laboratory and occasionally in the field (Platt 1975, Platt and Greenfield 1968, Covell 1994, Platt and Maudsley 1994, Platt et al. 2003, Ritland 1990). Ritland (1990) discussed factors favoring increased rates of hybridization in southern Georgia and northern Florida.

Credit: Donald W. Hall, UF/IFAS

Distribution

The red-spotted purple is resident from Florida westward to eastern Texas and northward into Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, New York, Vermont, and New Hampshire.

Description

Adults

The wing spread of adults is 3.0 to 3.5 inches (Daniels 2003). The upper surface of the front wings are black with thin marginal white dashes and submarginal, rows of oblong white and orange spots. The upper surfaces of the hind wings are black with iridescent blue patches and spots on the distal half. The undersides of the wings are brownish black with iridescent blue areas and with large orange basal spots, a row of bright orange spots, and two rows of curved iridescent blue dashes near the margins of the wings. The undersides of both wings have a row of curved marginal white dashes.

Credit: Donald W. Hall, UF/IFAS

Eggs

The eggs are whitish to pale green when first laid but later change to gray (Minno et al. 2005, Scott 1986). The egg surface is sculptured with small hexagons with spikes arising from the corners of the hexagons.

Credit: Donald W. Hall, UF/IFAS

Larvae

Full grown larvae are approximately 1.6 inches in length (Minno et al. 2005). The head is brown and fringed with short spines and has a cleft on top. The body is olive green to greenish brown with a pinkish white saddle and a white lateral line. There are a pair of long, thick, branched horns on top of the prothorax and a small pair of branched spines on top of the posterior end and several humps on the back. The larvae are bird-dropping mimics. They are very similar in appearance to viceroy larvae but are less spiny (Minno et al. 2005). Caterpillars of species in the genus Limenitis are our only horned bird dropping mimics (Wagner 2005).

Credit: Donald W. Hall, UF/IFAS

Pupae

The pupae are brown and white (possibly bird-dropping mimics). They hang vertically attached by the terminal end to a small silk pad by a cremaster.

Credit: Donald W. Hall, UF/IFAS

Credit: Donald W. Hall, UF/IFAS

Life Cycle and Biology

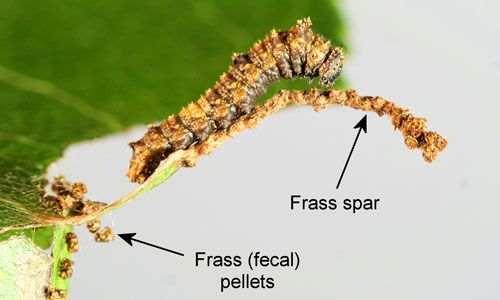

There are two generations per year in Florida. Eggs are laid near the tips of leaves, and the young larva eats most of the leaf tip, except for the midrib. The midrib is elongated into a "frass spar" by the addition of frass (fecal) pellets fastened together with silk. The larva then rests on the midrib/frass spar (Figure 7), returning to the leaf only to feed. The larva also attaches pieces of leaves and frass pellets to the base of the exposed midrib with silk. The frass spar and the frass pellets at the base of the midrib probably serve a defensive function – possibly by being repellent to potential predators.

Credit: Donald W. Hall, UF/IFAS

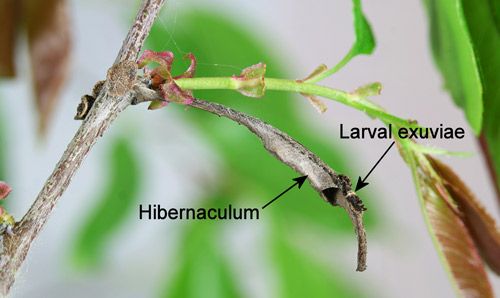

Third instar larvae overwinter in a small leaf shelter (hibernaculum) that is attached to the stem of the host plant with silk.

Credit: Donald W. Hall, UF/IFAS

Adults prefer to feed on tree sap, fermenting fruit, or dung, but they do occasionally take nectar from flowers, and also frequently feed at mud or drink from mud puddles (Allen 1997; Glassberg et al. 2000; Opler and Krizek 1984; Scott 1986).

Hosts

Preferred plant hosts for red-spotted purple larvae in Florida are black cherry (Prunus serotina Ehrh.) and deerberry (Vaccineum stamineum L.), occasionally willows—particularly Carolina willow (Salix caroliniana Michx.) and possibly species in the family Betulaceae. Plant names for Florida plants are from Wunderlin et al. (2019). In the northern US, a variety of other plants are used including aspens, poplars, cottonwood, hawthorn, birches, black oak, and serviceberry (Allen 1997; Cech and Tudor 2005; Opler and Krizek 1984; Scott 1986).

Credit: Jerry Bulter, UF/IFAS

Credit: Jerry Butler, UF/IFAS

Credit: Donald W. Hall, UF/IFAS

Credit: Donald W. Hall, UF/IFAS

Selected References

Allen TJ. 1997. The Butterflies of West Virginia and Their Caterpillars. University of Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. 400 pp.

Cech R, Tudor G. 2005. Butterflies of the East Coast: An Observer's Guide. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. 345 pp.

Covell CV Jr. 1994. Field observations of matings between female Limenitis archippus and male L. arthemis subspecies (Nymphalidae). Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 48: 199-204.

Daniels JC. 2003. Butterflies of Florida: Field Guide. Adventure Publications, Inc. Cambridge, Minnesota. 256 pp.

Glassberg J, Minno MC, Calhoun JV. 2000. Butterflies through Binoculars: Florida. Oxford University Press. New York, New York. 256 pp.

Minno MC, Butler JF, Hall DW. 2005. Florida Butterfly Caterpillars and Their Host Plants. University Press of Florida. Gainesville, Florida. 341 pp.

Opler PA, Krizek GO. 1984. Butterflies East of the Great Plains. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, Maryland. 294 pp.

Platt AP. 1975. Monomorphic mimicry in Nearctic Limenitis butterflies: experimental hybridization of the L. arthemis-astyanax complex with L. archippus. Evolution 29: 120-141.

Platt AP, Brower LP. 1968. Mimetic versus disruptive coloration in intergrading populations of Limenitis arthemis and astyanax butterflies. Evolution 22: 699-718.

Platt AP, Greenfield JC. 1971. Interspecific hybridization between Limenitis arthemis astyanax and L. archippus (Nymphalidae). Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 25: 278-284.

Platt AP, Maudsley JR. 1994. Continued interspecific hybridization between Limenitis (Basilarchia) arthemis astyanax and L. (B.) archippus in the southeastern U.S. (Nymphalidae). Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 48: 190-198.

Ritland DB. 1990. Localized interspecific hybridization between mimetic Limenitis butterflies (Nymphalidae) in Florida. Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 44: 163-173.

Scott JA. 1986. The Butterflies of North America: A Natural History and Field Guide. Stanford University Press. Stanford, California. 583 pp.

Wagner DL. 2005. Caterpillars of Eastern North America. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. 512 pp.

Wunderlin RP, Hansen BF, Franck AR, Essig FB. 2022. Atlas of Florida Plants (https://florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/). [SM Landry and KN Campbell (application development), USF Water Institute.] Institute for Systematic Botany, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida. (12 April 2022)