Introduction

Biological and distribution information for a tiphiid wasp species commonly found in Florida, Myzinum maculata, has not been extensively studied or reported in the available literature. Generalized Myzinum or tiphiid wasp (Hymenoptera: Tiphiidae) details will be provided when species-specific information cannot be provided.

Credit: Johnny Dell, http://www.bugwood.org/

Distribution

Myzinum contains 26 species in four genera that are found throughout Florida, with approximately 140 species occurring in a wide range of habitats across North America (Borror and Triplehorn 1989; Stange 1994). Specific distribution information for M. maculata is not available.

Description

Male and female tiphiid wasps differ in appearance, or are sexually dimorphic. The female is larger and more robust than the male. The female also spends more time on and in the ground.

Credit: Donald Spence, University of Florida

Credit: Donald Spence, University of Florida

Credit: Donald Spence, University of Florida

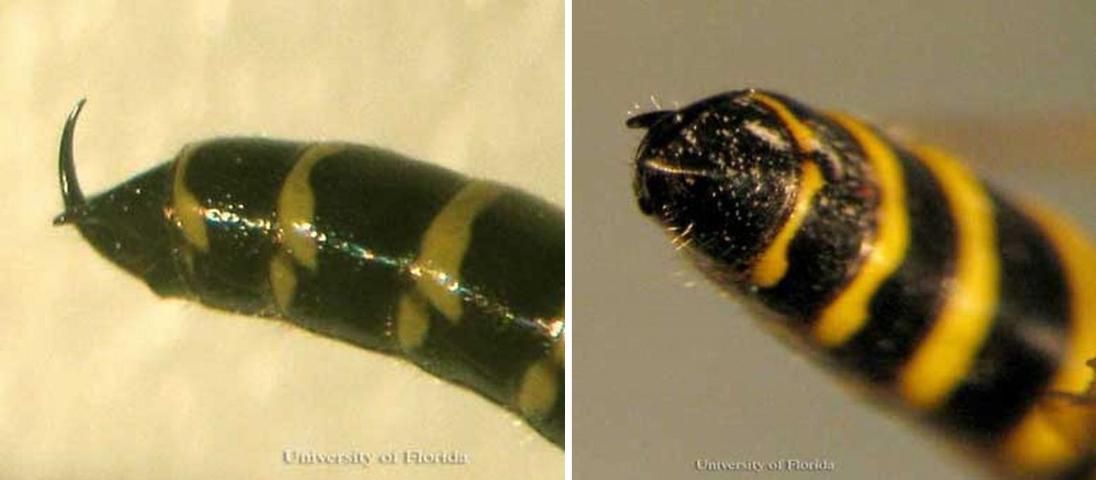

Myzinum maculata are mostly black and can be somewhat hairy. Females range from 11-18 mm (0.43-0.7 inch) in length, while males are 8-16 mm (0.31-0.63 inch). The abdomen has overlapping leaf-like plates, or lamellae, with alternating, conspicuous black and yellow bands.

The abdomen is covered with hairs, except for the metasoma (last segment), which is shiny. Both males and females may have alternating black and yellow bands. However, the male is much more slender and its abdomen is more cylindrical than the female. Males have an upward pointing spine at the end of the last abdominal segment. This spine looks like a stinger but is not (Borror and Triplehorn 1989).

Credit: Donald Spence, University of Florida

The thorax of both males and females is longer than broad. Males have two plate-like lobes that extend from a hardened plate (the mesosternum) on the underside of the thorax and over the bases of the middle coxae (UM 2009).

Credit: Donald Spence, University of Florida

Myzinum maculata males have a unique cleft front claw at the end of the terminal tarsomere.

Credit: Donald Spence, University of Florida

The wings of both males and females are tawny yellow. However, the wings of females are more yellowish than males'. Male wings are darker towards the tips and transparent or clear towards their base. The veins on the leading edges or both wings, or costal veins, are pronounced with a darker stigma (prominent wing cell) two-thirds out from the thorax. The wings of the males have six enclosed cells on the front wings (Goulet and Hüber 1993). The tegula (a hardened plate at the base of the front wing) does not completely cover the base of the wing.

Credit: Donald Spence, University of Florida

On the head, the compound eye sockets are notched or emarginated (Stange 1994). The labrum is folded in front and below the clypeus. There are three ocelli (simple eyes) between and above the eyes. Females have eleven antennal segments, while males have twelve. Antennae are smooth and filiform, or shaped like a thread or filament.

Credit: Donald Spence, University of Florida

Credit: Donald Spence, University of Florida

Life Cycle

Tiphiids are reported to be both pollinators (adults) and ectoparasites (larvae) (Tooker and Hanks 2000). Their polyphagous nature has not been thoroughly studied but Tooker and Hanks (2000) found that adults of species in the genus Myzinum feed on 22 species of plants, mostly in the Asteraceae and Apiaceae plant families (Tooker and Hanks 2000).

Tiphiids are generally parasitoids on the larvae of two Coleoptera insect families, Scarabaeidae and, to a lesser extent, Cicindelidae (Selmen 2008, Borror and Triplehorn 1989). Female tiphiids search out species of these subterranean beetle larvae and access them through tunnels they form or through tunnels formed by the adult beetles (Hanson 1995, Stange 1994, Krombein 1938). When a larva is found, the wasp will lay her eggs on the abdomen of the beetle larva, as an ectoparasite (Quicke 1997, Stange 1994, Schönitzer and Lawitzky 1987, Krombein 1938). The beetle larva becomes partially paralyzed during their development through the injection of neurotoxins (such as proline and polyamine) by the female wasp (Quicke 1997, Hanson 1995). The beetle larva is only partially paralyzed so that the wasp larva may initially feed on a living host (Quicke 1997). Once the wasp larva completely consumes the beetle larva, it constructs a cocoon for overwintering. Wasps emerge from cocoons in the spring (Krombein 1938).

Activity of the females from this point is not known (Krombein 1938). The males are known to congregate on vegetation early in the morning when temperatures are low, presumably waiting for females to emerge from the soil or to forage (Hanson 1995, Krombein 1938).

Hosts and Economic Importance

Tiphiid wasps are used as biological controls of white grubs in farm settings (Davis 1919) and as a turfgrass pest management strategy (Rogers and Potter 2004). Female wasps seek out beetle larvae in the ground. The female deposits an egg on the body of the grub. As the wasp larvae develop, they eat the beetle larvae. Biological controls such as this occur in nature, but as the populations of both species fluctuate, the level of parasitism changes from season to season.

Selected References

Borror D, Triplehorn C, Johnson N. 1989. An Introduction to the Study of Insects, Sixth Edition. Saunders College Publishing, New York. 875 pp.

Davis J. 1919. Contributions to a knowledge of the natural enemies of Phyllophaga. Bulletin of the Illinois Natural History Survey 13: 53–138.

Goulet H, Hüber J. 1993. Hymenoptera of the World: An Identification Guide to Families. Agriculture Canada Publication. 668 pp.

Hanson PE, Gauld ID. 1995. The Hymenoptera of Costa Rica. Oxford University Press, Oxford, England. 893 pp.

Krombein K. 1938. Studies in the Tiphiidae II, A revision of the Nearctic Myzininae (Hymenoptera: Aculeata). Transactions of the American Entomological Society 44: 227–292.

Quicke DLJ. 1997. Parasitic wasps. Kluwer Academic Publishers. New York, NY. 460 pp.

Rogers ME, Potter DA. 2004. Biology and conservation of Tiphia wasps, parasitoids of turf-infesting white grubs. Acta Hort. (ISHS) 661: 505–510.

Schönitzer K, Lawitzky G. 1987. A phylogenetic study of the antenna cleaner in Formicidae, Mutillidae, and Tiphiidae (Insecta, Hymenoptera). Zoomorphology 107: 273–285.

Selmen L. (2008). White grubs, Phyllophaga spp. Featured Creatures. http://entomology.ifas.ufl.edu/creatures/field/white_grub.htm (7 January 2010).

Stange L. 1994. The Tiphiid wasps of Florida (Hymenoptera: Tiphiidae). Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry. Entomology Circular No. 364 http://www.fl-dpi.com/enpp/ento/entcirc/ent364.pdf. 2 pp.

Tooker J, Hanks L. 2000. Flowering plant hosts of adult Hymenopteran parasitoids of Central Illinois. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 93: 580–588.

University of Minnesota (UM), Department of Entomology. (2009). Hymenoptera Family Characters. Insect Collection. https://insectcollection.umn.edu/hymenoptera (7 January 2010).