The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids, and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

Halictidae are one of the six bee families in the order Hymenoptera. Also known as sweat bees, halictids are a very diverse group of metallic and non-metallic bees. Halictids display the most diverse gradation in social behavior (Michener 2007) as species can be solitary, communal, semi-social, or primitively eusocial. This family also includes cleptoparasitic and social parasitic species.

Some species exhibit solitary or primitively eusocial behaviors across different populations depending on time of year, geographic location, altitude, and often unknown factors (Michener 2007). The genus Lasioglossum in Halictidae is one of the largest genera of bees worldwide, with an incredibly diverse array of behaviors.

Credit: Tim Lethbridge

Credit: UF/IFAS Honey Bee Lab

Distribution

Halictid bees are found worldwide, but are especially abundant in temperate regions. Halictidae is split into four subfamilies: Rophitinae, Nomiinae, Nomioidinae, and Halictinae. In Florida, there are over 50 species of Halictidae found within the subfamilies Nomiinae and Halictinae and including the following eight genera: Sphecodes, Lasioglossum, Nomia, Agapostemon, Augochloropsis, Augochlora, Augochlorella, and Halictus (Pascarella and Hall 2008). Most of these species are also common throughout the eastern United States.

Description

Halictid bees can vary greatly in appearance. While a select few are robust, most are slender bees. The majority of species are dull to metallic black, with the remaining species being metallic green, blue or purple. Female halictids carry pollen on the tibia and femur of their hind legs, except for parasitic species (e.g. Sphecodes) which do not carry pollen at all. Males usually resemble females of the same species except that they are often more slender, do not have scopa (area of long dense hairs on hind tibia used for carrying pollen), and sometimes have distinct yellow markings on the face, abdomen, and/or legs. Mature larvae are grub-like in appearance, without setae, and usually less than 15 mm long. Pupae are very delicate and rarely encountered due to their brief developmental period and unexposed nests (Michener 2007).

Credit: Jeff Hollenbeck

Credit: Tim Lethbridge

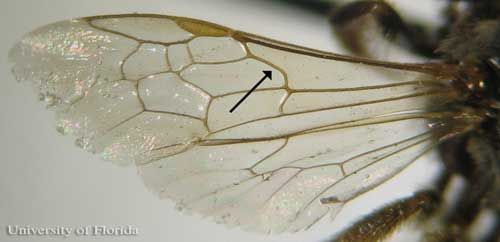

Halictidae can be separated from other families of bees by a strongly curved basal vein in the wing. The genus Lasioglossum can be further separated by weak or reduced wing veins.

Credit: UF/IFAS Honey Bee Lab

Credit: UF/IFAS Honey Bee Lab

Life Cycle

In social populations, there is some degree of cooperative brood care, division of reproduction and labor (e.g. queens and workers), and/or overlapping generations. For the vast majority of social Halictids, colonies are annual, lasting one year, and are initiated by a single female queen bee, typically in the spring (Wcislo and Engel 1996; Schwartz et al. 2007).

Solitary species of Halictids overwinter as prepupae or adults and most produce a single generation per year For bees that overwinter as prepupae, development to adulthood is completed in spring or summer. After finishing development, adult bees emerge, mate, and subsequently, females begin digging nests and provisioning cells with pollen and nectar. In each cell they lay a single egg. When the larva emerges from the egg, it consumes the pollen provision until the food is gone. The larva then defecates, enters the prepupal stage, and may or may not remain in this prepupal form for the rest of the year and over winter depending on the species. It is believed that some prepupae remain in that stage for a year or more depending on the species and on environmental conditions. Some prepupae, on the other hand, will pupate immediately but adults will remain in their cell over the winter before emerging in spring or summer, again depending on the species.

Credit: Beatriz Moisset

Foraging

Most species are polylectic, or gather floral resources including pollen and nectar from multiple plant species. There are a few oligolectic species and subgenera that feed from a single plant family. All halictids are mass provisioners, that is, the adults provision each cell with all the food (pollen and nectar) a larva will need until it emerges.

Credit: Lynette Schimming

Nesting Behavior

Most halictids nest underground, though others nest aboveground in rotting wood or other substrates. Nest architecture of halictids that nest in rotting rood is irregular, usually due to the nature of the wood, but can resemble ground nests (Eickwort and Eickwort 1973). Nest cells usually are lined with a waxy substance likely extruded from the bee's Dufour's gland (a gland found on the underside of the abdomen). Species that are parasites (e.g. Sphecodes spp.) do not build nests at all but rather usurp nests of other species. Despite usually nesting in the ground, nesting behavior is otherwise highly variable between the species. Each subfamily has its own characteristic nesting habit:

- In Rophitinae, larval cells typically are excavated either at a slant or horizontally off of a main lateral tunnel.

- Nomiinae build vertical cells, sometimes in clusters.

- Nomioidinae nest in sub-horizontal cells off of vertical burrows. Halictinae have diverse nest types, including series of cells, scattered cells, and clusters of cells. The area around the clusters sometimes is excavated.

Credit: Ettore Balocchi

Credit: UF/IFAS Honey Bee Lab

Cleptoparasites

The family Halictidae contains a few social parasites and cleptoparasitic bee genera. These include Sphecodes, Microsphecodes (not present in Florida) and some Lasioglossum species. These genera are primarily cleptoparasites of other halictids or bees of similar size. Sphecodes females typically kill the egg or larva in the cell before they lay an egg, but in most other cleptoparasitic species, eggs are laid on unfinished cell walls or through sealed cells and the larva of the cleptoparasite kills the other egg or larva before eating the host's stored food (Michener 2007).

Credit: Tim Lethbridge

Management

Sweat bees are very important pollinators for many wildflowers and crops, including stone fruits, pomme fruits, alfalfa and sunflower. Sweat bee populations can be encouraged with wildflower plantings and by providing nesting areas. Halictids typically nest in bare soil located in a sunny location. Minimum tillage and insecticide use will help to increase populations of Halictidae and other soil nesting bees.

Credit: Katie Buckley, University of Florida

Selected References

Eickwort G. C, and Eickwort K. R. 1973. "Notes on the nests of three wood-dwelling species of Augochlora from Costa Rica (Hymenoptera: Halictidae)." Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 46:17–22.

Michener C. D. 1994. pp. 134–141. The Bee Genera of North and Central America (Hymenoptera: Apoidea). Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC.

Michener C. D. 2007. pp. 6–11, 23–29, 57–58, 319–412. The Bees of the World, 2nd Edition. The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD.

Pascarella J. B., and Hall H. G. (2008). The Bees of Florida. https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/hallg/melitto/intro.htm

Schwarz, M. P., M. H. Richards, and B. N. Danforth. 2007. "Changing paradigms in insect social evolution: Insights from Halictine and Allodapine bees." Ann. Rev. Entomol. 25: 127–150.

Stehr F. W. 1987. pp. 691–693. Immature Insects, Vol 1. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company: Dubuque, IA.

Wcislo W. T., and Engel M. S. 1996. "Social behavior and nest architecture of Nomiine Bees (Hymenoptera: Halictidae; Nomiinae)." Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 69:158–167.