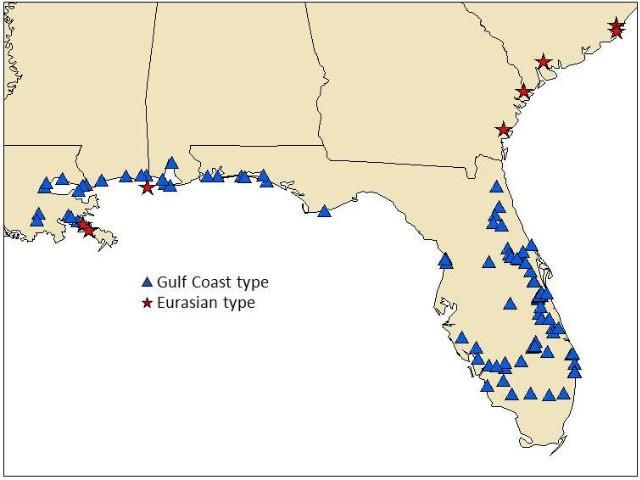

Phragmites is a tall, perennial, wetland grass, occurring in both fresh and brackish waters in North American. Phragmites can be divided into three genetic lineages: native North America types, a Gulf Coast type, and a Eurasian type. The native types are found in the northeast, Midwest and western United States, but not in the southeast. The Gulf Coast lineage occurs widely from the Atlantic coast of Florida, along the Gulf Coast from Florida to Texas and south into Mexico and Central and South America (Meyerson et al. 2009). The Eurasian lineage was introduced into Philadelphia with ships ballast in the 1800s (Burk 1877), and has become increasingly abundant and widespread in North America. It is now the dominant type along the Atlantic coast from Georgia northwards, and has moved into the Midwest, the Mississippi River Delta, and western states (Saltonstall 2002).

Native and Eurasian Phragmites are currently considered to be the same species, Phragmites australis, while the Gulf Coast type is thought to be the result of hybridization between an African species, Phragmites mauritianus and P. australis (Lambertini et al. 2012). The Gulf Coast type may represent an early introduction from Africa.

Eurasian Phragmites was discovered for the first time in Florida in 2013 in Lake Seminole, Pinellas Co. (Overholt et al. 2014), and efforts are underway to eradicate this population. Prior to this finding, the closest Eurasian Phragmites had been found to Florida was 42 miles north of the Florida/Georgia border along Interstate 95, and 60 miles west of Florida on Petit Bois Island, Mississippi (Williams et al. 2012). Due to the proximity of the Eurasian type to Florida, it would seem likely that it will eventually reinvade the state.

Reproduction of Phragmites

There are reports of prolific seed production in populations of Phragmites (see references in Pellegrin and Hauber 1999), but in the Gulf Coast, little or no seed production has been observed (Hauber et al. 1991; Ward 2010; Williams et al. 2012). The lack of seed may be due to self-incompatibility, as most plants at a given location could belong to a single clone. Phragmites does spread through the growth of rhizomes, and it is thought that the majority of spread within a population is due to clonal growth. Broken pieces of rhizomes may be responsible for dispersal of Phragmites along water courses. How Gulf Coast Phragmites became so widespread in the southeastern United States with little or no seed production is not known.

Why be concerned about possible invasion of exotic Phragmites into Florida?

The Eurasian type of Phragmites has proven to be a highly aggressive invader, particularly in the northeastern and mid-Atlantic states, where it has largely displaced native Phragmites (Myerson et al. 2009). A study conducted in the Mississippi River Delta in Louisiana demonstrated that the Eurasian type can out-compete the Gulf Coast type (Howard et al. 2008). Thus, the Eurasian Phragmites may have the potential to displace Gulf Coast Phragmites and other wetland plants if it invades Florida.

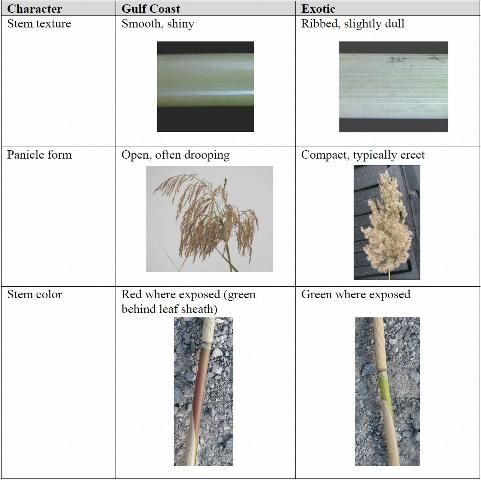

How can Gulf Coast and Eurasian Phragmites be distinguished?

Eurasian and Gulf Coast Phragmites are morphologically distinct, and can be separated by three characters indicated in the table below. Fine longitudinal ribbing on the stems of Eurasian Phragmites may be the best character to separate the two types. The ribbing can be detected visually, but also by slowly rotating the stem under a finger nail.

References

Burk, I. 1877. "List of plants recently collected on ships' ballast in the neighborhood of Philadelphia." Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 29: 105–109.

Hauber, D. P., D. A. White, S. P. Powers and F. R. Defrancesch. 1991. "Isozyme variation and correspondence with unusual infrared reflectance patterns in Phragmites australis (Poaceae)." Plant Systematics and Evolution 178: 1–8.

Howard, R. J., S. E. Travis and B. A. Sikes. 2008. "Rapid growth of a Eurasian haplotype of Phragmites australis in a restored brackish marsh in Louisiana, USA." Biological Invasions 10: 369–379.

Lambertini, C., I. A. Mendelssohn. M. H. G. Gustafsson, B. Olesen, T. Riis, B. K. Sorrell and H. Brix. 2012. "Tracing the origin of gulf coast Phragmites (Poaceae): A story of long-distance dispersal and hybridization." American Journal of Botany 99: 538–551.

Meyerson, L. A., K. Saltonstall and R. M. Chambers. 2009. Phragmites australis in Eastern North America: A historical and ecological perspective. pp. 57-82. In: B. R. Silliman, E. Grosholz and M. D. Bertness (eds.). Salt Marshes Under Global Siege. Univ. of Cal. Press.

Overholt, W. A., M. P. Sowinski, D. C. Schmitz, J. Schardt, V. Hunt, D. J. Larkin and J. B. Fant. 2014. "Early detection and rapid response to an exotic Phragmites population in Florida." Aquatics Magazine 36 (3): 5–7.

Pellegrin, D. and D. P. Hauber. 1999. "Isozyme variation among populations of the clonal species, Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steudel." Aquatic Botany 63: 241–259.

Saltonstall, K. 2002. "Cryptic invasion by a non-native genotype of the common reed, Phragmites australis, into North America." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99: 2445–2449.

Ward, D. B. 2010. "North America has two species of Phragmites (Gramineae)." Castanea 75: 394–401.

Williams, D. A., M. Hanson, R. Diaz and W. A. Overholt. 2012. "Determination of common reed (Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steudel) varieties in Florida." Journal of Aquatic Plant Management 50: 69–74.