Introduction

The European pepper moth, Duponchelia fovealis (Zeller), is a native to both freshwater and saltwater marshlands of southern Europe (mainland Spain, parts of France, and Portugal), the eastern Mediterranean region (Greece, Italy, Corsica, Macedonia (the original area that was part of the former Yugoslavia), Malta, Crete, Sardinia, and Sicily), the Canary Islands, Syria, and Algeria (Bonsignore and Vacante 2010; CABI 2010; Faquaet 2000; MacLeod 1996; Guda et al. 1988). In Malta, it is fairly common in gardens and orchards, and has been noted to overwinter outdoors, reproducing on wild plants in northern Italy (Anonymous 2005a).

Fairly recently (since 1984), this moth became a notable greenhouse pest in northern Europe and Canada for the cut flower, vegetable, and aquatic plant industries (Ahern 2010; Brambila and Stocks 2010; CABI 2010; Anonymous 2005a; Anonymous 2005b; McLeod 1996). It has also become a pest of lisianthus and strawberries grown commercially in its native Italy (Bonsignore and Vacante 2010; Guda et al. 1988). After initial California greenhouse infestations were reported, European pepper moth was detected in several eastern U.S. states. However, established populations in the landscape have not been confirmed and economic damage outside of the greenhouse industry has also not been reported (Gill 2013; Ingerson-Mahar 2014; White 2013).

Distribution

Worldwide

The European pepper moth is native to the Mediterranean region of Europe, but it has expanded its range primarily as a greenhouse pest into other parts of Africa and the Middle East, northwest India, Europe, Canada, and the United States. (Ahern 2010; Bonsignore and Vacante 2010; CABI 2010; Anonymous 2005a; Anonymous 2005b; Faquaet 2000; McLeod 1996; Billen 1994).

United States

In the United States, it was detected on begonia in San Diego County, California, in 2004 (though it was subsequently not detected in 2005 and considered to be eradicated). The European pepper moth was detected again in San Diego County, California and has subsequently been reported in the following counties as of 2013: Fresno, Imperial, Kern, Los Angeles, Monterey, Orange, Riverside, San Diego, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Barbara, Ventura, San Luis Obispo, and San Bernardino (Bethke and Bates 2014). Although a citation has not been provided, Bethke and Bates (2014) report the European pepper moth as established in the following states: Alabama, Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Hawaii, Minnesota, Mississippi, New York, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Carolina, Texas, and Washington. As of December 2014, the reporting of established populations in Florida from California scientists is considered to be erroneous as established and reproducing populations of European pepper moth have not been detected in the landscape despite extensive monitoring from state of Florida (Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry-FDACS-DPI) and University of Florida laboratories (Hodges, G. personal communication). Furthermore, survey maps provided by the Cooperative Agricultural Pest Survey Program only support establishment by survey in total of nine counties within the following eastern U.S. states: Maryland, Mississippi, New York, and Pennsylvania (NAPIS 2014). The potential of widespread establishment in the Florida and southeastern U.S. is unknown, but researchers and extension specialists are aware of its pest potential. Suspect established populations of European pepper moth should be reported to FDACS-DPI (http://www.freshfromflorida.com/Divisions-Offices/Plant-Industry) or the University of Florida's Insect Identification Laboratory (http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/insectid/index.html).

Description

Adults

The adults have a wingspan of 19 to 21 mm (0.75 to 0.83 inch). The forewings are gray-brown in color with two yellowish-white transverse lines. The outermost of these lines has a pronounced "finger" that points towards the back edge of the wing. When at rest, the wings are held out from the body forming a triangle. The adult body measures 9 to 12 mm (0.35 to 0.5 inch) in length. The head, antennae, and body are olive brown. The abdomen has cream-colored rings encircling it. The legs are pale brown (Bethke and Vander Mey 2010; Bonsignore and Vacante 2010; Brambila and Stocks 2010; CABI 2010; Hoffman 2010; Anonymous 2005b; Trematerra 1990; Guda et al. 1988).

Credit: Carmelo Peter Bonsignore, Università degli Studi Mediterranea di Reggio Calabria

The male's abdomen curves upwards when at rest, at almost 90 degrees from horizontal. Males have a longer, slimmer abdomen compared to females. In fact, the abdomen of the male is unusually long for most moths as it extends beyond the wings (Bethke and Vander Mey 2010; Bonsignore and Vacante 2010; Brambila and Stocks 2010; CABI 2010; Hoffman 2010; Anonymous 2005b; Trematerra 1990). The hindwings cannot be seen unless the specimen is spread. When they are, the hindwings of both sexes are pale-olive brown with a cream-colored wavy line crossing the middle of the wing (Bonsignore and Vacante 2010; CABI 2010; Trematerra 1990).

Credit: James Hayden, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry

Credit: Carmelo Peter Bonsignore, Università degli Studi Mediterranea di Reggio Calabria

Unknown (2006a) and Pijnakker (2001), noted that the adults (presumably both males and females) fly low and fast with their abdomen curved upwards, which gives the species a unique flight pattern. In addition, it has been noted that in heavy infestations, the adults can move in swarms (Unknown 2006a).

Eggs

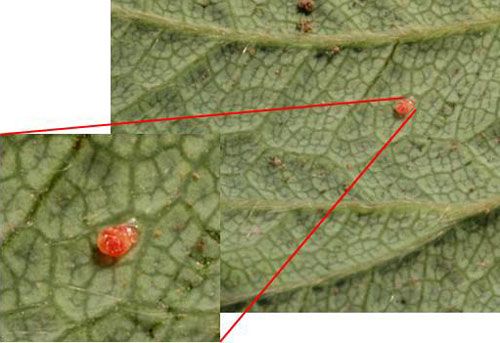

The eggs measure 0.5 X 0.7 mm (0.02 X 0.03 inch) and are whitish-green or straw-colored when laid. Eggs turn pink then red as the embryo develops, finally turning brown prior to hatching. They are laid singly or in masses of three to 10 (overlapping like roof tiles) mostly on the undersides of leaves (close to the veins) though they can also be found on the upper surface of the leaf, on the stalks, at the base of the plant, or in the upper soil layer (Bethke and Vander Mey 2010; Bonsignore and Vacante 2010; Brambila and Stocks 2010; CABI 2010; Hoffman 2010; Anonymous 2005a; Anonymous 2005b; Billen 1994; Trematerra 1990; Guda et al. 1988).

Credit: Carmelo Peter Bonsignore, Università degli Studi Mediterranei di Reggio Calabria

Credit: Lance Osborne, University of Florida

Credit: Pasquale Trematerra, Università degli Studi Molise, Italia

Females have also been documented laying eggs on furnishings within the greenhouse (Jackel et al. 1996). In addition, eggs being laid on the fruit have been recorded (Lance Osborne personal communication).

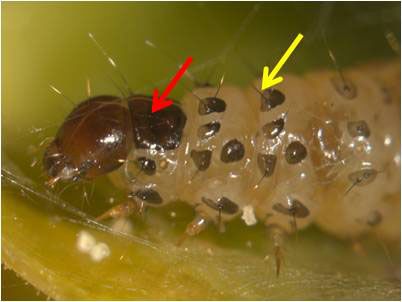

Larvae

Upon hatching, the larvae measure 1.5 mm (0.06 inch) in length and have a shiny dark head and a salmon pink body with a line of separated brown to gray spots extending across and around each segment. On some segments there are two transverse rows of these spots. If you look at these spots with a hand lens, you will see at least one short, stout hair emerging from each of them. There is also a hard dorsal plate (or sclerotized region) located on the segment just behind the head. This plate is the same color as the head capsule (Bethke and Vander Mey 2010; Bonsignore and Vacante 2010; Brambila and Stocks 2010; CABI 2010; Hoffman 2010; Trematerra 1990; Guda et al. 1988).

Credit: Lyle Buss, University of Florida

Credit: Marja van der Straten, Plant Protection Service, Wageningen, the Netherlands

As the larvae grow, their background color changes to a creamy white or light brown or dirty white color (CABI 2010; Trematerra 1990). The color apparently varies depending on the host plant (CABI 2010; Guda et al. 1988). In some cases, the background color of the larvae can even be quite dark (due to recent feeding activity) making the spots hard to see. Prior to pupation, they can reach 17 to 30 mm (0.7 to 1.25 inch) long and become pearly in appearance. They also seem to lose their spots just before pupation. (Anonymous 2005b; Trematerra 1990).

Credit: Lyle Buss, University of Florida

Marek and Bártová (1998) state that the larvae are photophobic (having an intolerance of light) and when they are exposed to light, they move back and forth vigorously. It has also been noted that when feeding on the aquatic hosts, they do not seem to mind the leaves being submerged in water (CABI 2010; Billen 1994).

Pupae

The pupae undergo pupation in a cocoon made of webbing, frass, and soil particles. The cocoon measures 15 to 19 mm (0.6 to 0.75 inch). The pupa itself is yellow brown in color (becoming darker as the adult gets closer to emergence) and measures 9 to 12 mm long (0.35 to 0.5 inch) (Bethke and Vander Mey 2010; Bonsignore and Vacante 2010; Brambila and Stocks 2010; CABI 2010; Hoffman 2010; Anonymous 2005b; Trematerra 1990; Guda et al. 1988).

Credit: James Hayden, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry

Life Cycle and Biology

The length of development for this pest varies according to temperature. In a greenhouse setting (at 68°F or 20°C), the development time is four to nine days for the eggs; three to four weeks for the larvae; one to two weeks for pupation; and one to two weeks for adults (six to eight weeks in total). The adults quickly mate with females laying eggs within 24 hours of emergence. The females are capable of laying 200 eggs during their lifetime. In a greenhouse setting, eight to nine generations per year have been recorded (Ahern 2010; Bethke and Vander Mey 2010; Bonsignore and Vacante 2010; Brambila and Stocks 2010; CABI 2010; Hoffman 2010; Unknown 2006a; Anonymous 2005a; Anonymous 2005b; Jackel et al. 1996; Pijnakker 2001; Romeijn 1996). In the warm climates of California and the southeastern United States, the potential for multiple brood production and a shortened life cycle is quite high (Bethke and Vander Mey 2010; Brambila and Stocks 2010).

This pest does not seem to be cold tolerant and the literature suggests that this insect does not undergo hibernation or diapause. In northern climates, it is mainly a pest of greenhouses (though it may be found outside during warm summer months, dying off when it becomes cold) (Ahern 2010; Brambila and Stocks 2010; CABI 2010; Hoffman 2010; Anonymous 2005a; Anonymous 2005b; Faquaet 2000). Based on these observations, in warmer, humid climates, it may be possible to find the species outside in the landscape for longer times. It is worth noting that the lack of observations of hibernation or diapause may only apply to greenhouses that are in continuous operation and for areas such as the Canary Islands where it has been noted that they produce broods continuously because of a fairly constant climate year round.

However, one paper notes that the moth can overwinter in the pupal stage (Unknown 2006a). The ability of the European pepper moth to overwinter in the pupal stage corresponds with notations describing the presence of adults in parts of its native range from April to May and from August to October, producing at least two broods a year (Ahern 2010; CABI 2010; Anonymous 2005b; Faquaet 2000; Marek and Bártová 1998; Guda et al. 1988). The observation that it could hibernate in a pupal stage in areas with less extreme winter temperatures could have a large affect on the level of pest this species could become in the United States.

Dispersal

Adults are good fliers (upwards of 100 km or 62 miles), but they can also be dispersed through propagative and non-propagative material such as fruit, herbs, fresh vegetable products, and cut flowers, because they can bore into stems and fruit and are well hidden among the soil and leaves as well as between the container sides and the soil (CABI 2010; Derksen and Whilby 2010; Hoffman 2010; Anonymous 2005a; Anonymous 2005b; Stocks and colleagues personal observation). In one paper, a reference indicates that the European pepper moth has been dispersed on mother-in-law's tongue, Sansevieria, and croton, Codiaeum variegatum through the commercial shipping of these plants, though there is nothing in the literature indicating that these plants are actually hosts (Unknown 2006b).

Host Plants

The European pepper moth has been listed as a pest on at least 35 species of plants ranging from aquatic plants to crop plants to plants grown in the nursery and floriculture trade. They are as follows:

-

Alternanthera splendid, an aquatic plant

-

Alternanthera rosaefolia, an aquatic plant

-

Apium graveolens, celery

-

Bacopa lanigera, water hyssop

-

Begonia tuberosa

-

Begonia elatior

-

Bellis perennis, English daisy

-

Beta vulgaris, beets

-

Capsicum annuum, pepper

-

Chenopodium album, lamb's quarters

-

Convolvulus arvensis, bindweed

-

Cuphea hyssopifolia, false heather

-

Echinodorus tropica, sword plant

-

Echinodorus parviflorus, sword plant

-

Euphorbia pulcherrima, poinsettia

-

Eustoma grandiflorum, Lisianthus

-

Ficus triangularis, fig

-

Hyeronima alchorneoides, a tropical tree of South American origin so it is probably a transplanted landscape tree

-

Hygrophila rubella, an aquatic plant

-

Ludwigia glandulosa, an aquatic plant

-

Ludwigia perennis, an aquatic plant

-

Malva sylvestris, mallow

-

Mentha pulegium, penny royal

-

Nesaea pedicellata, an aquatic plant

-

Ocimum basilicum, basil

-

Origanum majorana, majorum

-

Oxalis acetosella, common wood sorrel

-

Plantago lanceolata, plantain

-

Portulaca oleracea, common purslane

-

Punica granatum, pomegranate

-

Ranunculus repens, creeping buttercup

-

Rotala macranda, an aquatic plant

-

Rotala wallichii, an aquatic plant

-

Rubus fruticosus, blackberry

-

Solanum lycopersicum, tomatoes

Additionally, damage notes in the literature include the following genera:

-

Amaranthus

-

Anemone

-

Annona

-

Anthurium

-

Bouvardia

-

Calathea

-

Chrysanthemum

-

Cineraria

-

Codiaeum

-

Coleus

-

Cucumis, cucumbers

-

Cucurbita, squash

-

Cyclamen

-

Fragaria, strawberries

-

Gerbera, African daisies

-

Heuchera, coral bells

-

Impatiens

-

Kalanchoe

-

Lactuca, lettuce

-

Limonium, sea lavender

-

Lysimachia

-

Ophiopogon, mondo grass

-

Pelargonium, geranium

-

Paeon

-

Phalaenopsis, orchids

-

Rhododendron, azalea

-

Rosa, roses

-

Rumex

-

Sambucus, elderberry

-

Sarracenia

-

Senecio

-

Tanacetum

-

Thymus, thyme

-

Ulmus, elm

-

Zea, corn

The European pepper moth also attacks certain aquatic plants such as Aponogeton and Cryptocoryne (Ahern 2010; Bethke and Vander Mey 2010; Bonsignore and Vacante 2010; Brambila and Stocks 2010; CABI 2010; Hoffman 2010; DeVenter 2009; Unknown 2006a; Anonymous 2005a; Zimmermann 2004; Clark 2000; Marek and Bártová 1998; MacLeod 1996; Romeijn 1996; Billen 1994; Guda et al. 1988).

In fact, the European pepper moth's natural habitat is freshwater and saltwater marshlands, so ornamental aquatic plants (especially if grown in a greenhouse setting) are particularly susceptible. As European pepper moth is mainly a threat to cultivated crops, it does not seem to represent much of a threat to biodiversity in natural ecosystems; however, it is prudent to remember that not much is known about its ecology in its native habitat (including what plants its feeds on in the marshlands). Therefore, there is potential for it being an environmental threat (Ahern 2010).

Economic Importance

Virtually all of the plants listed above either are or can be grown in Florida, many of them commercially and most of them can be maintained in a homeowner's yard. Florida's crop plants that are probably the most at risk from this pest include the following:

-

corn ($227,154,000)

-

cucumbers ($101,550,000)

-

green peppers ($198,553,000)

-

squash ($51,480,000)

-

tomatoes ($520,205,000)

-

strawberries ($313,632,000)

(US$ sales for 2009 - data obtained from USDA-ERS).

Damage

The European pepper moth inflicts damage to roots, leaves, flowers, buds and fruit on which it feeds as larvae (Ahern 2010; Bethke and Vander Mey 2010; Anonymous 2005a; Anonymous 2005b; Bonsignore and Vacante 2010; CABI 2010; Hoffman 2010; Murphy 2005; Messelink and Van Wensveen 2003; Pijnakker 2001). In leaves, this feeding damage appears first as rounded or crescent-shaped bites on the outside of the leaves, but eventually the whole leaf is eaten (Bonsignore and Vacante 2010; Marek and Bártová 1998; Romeijn 1996; Guda et al. 1988). The leaves that are attacked are usually at the base of the plant, but leaves higher in the canopy can also be attacked if the plants are placed very close together (Ahern 2010; Brambila and Stocks 2010; CABI 2010; Messelink and Van Wensveen 2003).

Credit: Carmelo Peter Bonsignore, Università degli Studi Mediterranei di Reggio Calabria

Credit: Marja van der Straten, Plant Protection Service, Wageningen, the Netherlands

Late instar larvae can even burrow into soft woody or herbaceous plant stems causing more damage (i.e., withered or dried crowns and stem collapse) (Ahern 2010; Bethke and Vander Mey 2010; CABI 2010; Hoffman 2010; Anonymous 2005a; Anonymous 2005b; Murphy 2005; Pijnakker 2001; Romeijn 1996; Guda et al. 1988). The holes left by the boring of this pest into the stem can facilitate infection by the fungus Botrytis cinerea (Guda et al. 1988).

Credit: Jim Bethke, Department of Entomology, University of California, Riverside

In potted plants, where the soil is not hard packed around the roots, the larvae can be found below the soil line, sometimes feeding on roots (Ahern 2010; CABI 2010; Messelink and Van Wensveen 2003; Pijnakker 2001; Guda et al. 1988). They also feed on decaying plant debris (Anonymous 2005a; Anonymous 2005b; Murphy 2005; Pijnakker 2001). In fact, MacLeod (1996), Romeijn (1996), Messelink and Van Wensveen (2003), and Murphy (2005), report that while there is no feeding damage to live roses, high numbers of larvae can be found in rose detritus that could serve as a source of infestation for other plants.

Sometimes the European pepper moth eats so aggressively that only the naked caules (stem or stalk of the plant) are left (Marek and Bártová 1998). Other times, external damage can only be detected when there are heavy infestations because it can bore into the stems. The leaves can even appear to develop normally, and the grower does not know he has the pest until the damage is already done (Unknown 2006a). The stems will then collapse suddenly, without the darkening of the stem associated with fungal diseases (Unknown 2006a; Billen 1994).

Monitoring

Monitoring for this pest may be necessary for controlling its population levels by helping to coordinate biological and chemical control measures (Bonsignore and Vacante 2010; DeVenter 2009; Guda et al. 1988). Water traps seem to be the most effective means of capturing the males of this insect, followed by delta traps, and funnel traps (all using the pheromone as bait) (Bonsignore and Vacante 2010; Brambila and Stocks 2010; DeVenter 2009; Zandigiacimo and Buian 2007). Light trapping (ultraviolet or blue light) can also be used to monitor the population (CABI 2010; Anonymous 2005a; Pijnakker 2001; MacLeod 1996; Romeijn 1996).

Inspection for caterpillars, pupae, and adults is also necessary. Look for signs of the caterpillars' presence, such as webbing (i.e., feeding tunnels), leaves spun together to form tunnels (particularly at interface of leaves and soil), life stages, and frass along with feeding damage, leaf wilting, and stem collapse (from larval tunneling) (Bonsignore and Vacante 2010; Brambila and Stocks 2010; Anonymous 2005b; Romeijn 1996). In addition, be sure to look at the interface between the soil and the leaves, between the soil and the container sides, and in detritus found around the crop (Ahern 2010; Brambila and Stocks 2010; Stocks and colleagues personal observation). In containerized plants, be sure to look around the base of pots and in detritus next to the pots. Cocoons have been found along the bottom edges of the container next to detritus, but can also be found on low lying leaves (Stocks and colleagues personal observation; Guda et al. 1988).

Credit: Lyle Buss, University of Florida

Credit: Lyle Buss, University of Florida

Adults are nocturnal and like sheltered areas (such as under vegetation or on the outside of the containers [especially when these containers are grouped together forming a larger sheltered area). When the adults are disturbed, their flight is short and irregular or they can drop to the ground below (Bonsignore and Vacante 2010; Guda et al. 1988; Stocks and colleagues personal observation]). The detection of the eggs is difficult and requires a certain level of expertise to accomplish. Sampling of the other life stages is easier and less costly (Bonsignore and Vacante 2010).

Management

Management for this pest includes biological, cultural, and chemical controls and should be coordinated with population monitoring.

Biological Control. All of these biocontrol agents can be ordered for commercial use. Application recommendations (and methods) vary, so be sure to read the label.

Biocontrol agents for the larval stage includethe following:

-

Bt - which is a formulation of the toxin produced by Bacillus thuringiensis

-

Dalotia coriaria - a rove beetle (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae), though it may be listed commercially as Atheta coriaria

-

Heterorhabditis bacteriophora and Steinernema spp. - entomopathogenic nematodes (Nematoda: Rhabditida)

(Ahern 2010; Bethke and Vander Mey 2010; Bonsignore and Vacante 2010; Brambila and Stocks 2010; CABI 2010; Zandigiacimo and Buian 2007; Unknown 2006b; Anonymous 2005a; Messelink and Van Wensveen 2003; Pijnakker 2001; Jackel et al. 1996; MacLeod 1996).

Biocontrol agents for the egg stage include the following:

-

Gaeolaelaps aculeifer - a predatory mite (Acari: Mesostigmata: Laelapidae) that may be listed commercially as Hypoaspis aculeifer

-

Dalotia coriaria - a rove beetle (see agents for larval stage)

-

Stratiolaelaps scimitus - a predatory mite (Acari: Mesostigmata: Laelapidae) that may be listed commercially as Hypoaspis miles

-

Trichogramma evanescens, T. cacoeciae and T. brassicae - parasitoid wasps (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae)

(Bonsignore and Vacante 2010; Brambila and Stocks 2010; CABI 2010; Zandigiacimo and Buian 2007; Unknown 2006b; Anonymous 2005a; Zimmermann 2004; Messelink and Van Wensveen 2003; Jackel et al. 1996).

Cultural Control. As European pepper moth feeds on plant detritus and debris, cultural control such as the removal of plant material refuse and weeds from production areas may be useful. Also, the removal of lower leaves of the plant that contact the soil may reduce the availability of optimally moist microhabitats (Brambila and Stocks 2010; Zandigiacimo and Buian 2007; Unknown 2006b; Anonymous 2005a). If you are in a greenhouse setting, installing insect nets is necessary for the control for not only this pest, but others (Zandigiacimo and Buian 2007; Unknown 2006b; Anonymous 2005a).

Chemical Control. Targeted spraying of the plants may be better than broadly spraying the area because of larval behavior (i.e., burrowing into the stem or fruit, forming webbing tunnels between the leaves and the soil, etc.) (Ahern 2010; Bethke and Vander Mey 2010; Brambila and Stocks 2010; Anonymous 2005a; Pijnakker 2001; Guda et al. 1988). Large droplets size is recommended (Bethke and Vander Mey 2010). Contact insecticides are recommended for use before the larvae bore into the stem; after the larvae have bored into the stem, however, systemic applications of those chemicals that can be applied through the irrigation water were recommended (Unknown 2006b; Arzone et al. 2002). In a greenhouse setting, the adults can be treated with an aerosol or fog and applied at night to take advantage of their nocturnal activity (Bethke and Vander Mey 2010).

Selected References

Ahern R. (September 2010). Amended New Pest Advisory Group Report. Duponchelia fovealis Zeller: Lepidoptera/Pyralidae. UF/IFAS Pest Alert. http://entomology.ifas.ufl.edu/pestalert/Duponchelia_fovealis_NPAG_ET_Report_20100917.pdf (29 September 2011).

Anonymous. (2005a). Risk management decision document for Duponchelia fovealis in Canada. Canadian Food Inspection Agency. UF/IFAS Pest Alert. http://entomology.ifas.ufl.edu/pestalert/duponchelia_fovealis_risk_management.pdf (30 September 2011).

Anonymous. (December 2005b). Plant Pest Information: Duponchelia fovealis Zeller. Canadian Food Inspection Agency. UF/IFAS Pest Alert. http://entomology.ifas.ufl.edu/pestalert/duponchelia_fovealis_canada.pdf (30 September 2011).

Arzone A, Tavella L, Alma A. 2002. Evoluzione dei problemi entomologici delle coltivazioni floricole e florovivaistiche. Informatore Fitopatologico 52(2): 22-31.

Bethke J, Vander Mey B. Pest Alert: Duponchelia fovealis. University of California Cooperative Extension, San Diego. http://ucanr.org/sites/cetest/files/55177.pdf (29 September 2011).

Bethke JA, Bates LM. (2014). European pepper moth. Center for Invasive Species Research. http://cisr.ucr.edu/european_pepper_moth.html (17 December 2014).

Billen W. 1994. On the harmfulness of Duponchelia fovealis (Zeller, 1847) in Germany (Lepidoptera, Pyralidae). Nota Lepidopterol 16(3/4): 212.

Bonsignore CP, Vacante V. 2010. Duponchelia fovealis (Zeller). Une nuova emergenza per la fragola? Protezione delle colture, pp. 40-43.

Brambila J, Stocks I. (December 2010). The European pepper moth, Zeller (Lepidoptera: Crambidae), a Mediterranean pest moth discovered in central Florida. http://www.freshfromflorida.com/content/download/23893/486212/duponchelia-fovealis.pdf (10 September 2014).

CABI International. (2010). Selected sections for: Duponchelia fovealis (southern European marshland pyralid). Crop Protection Compendium. http://www.cabi.org/cpc/ (30 September 2011).

Clark JS. 2000. Duponchelia fovealis (Zell.) arriving on imported plant material. Atropos 10: 20-21.

Derksen A, Whilby L. (2011). Update on Florida CAPS trapping activities for Duponchelia fovealis Zeller, September 2010 to May 2011. CAPS Report. http://www.cabi.org/cpc/ (30 September 2011).

DeVenter P van. (2009). Water trap best for catching Duponchelia. In the Greenhouse. https://research.wur.nl/en/publications/water-trap-best-for-catching-duponchelia (8 February 2023).

Faquaet M. 2000. Duponchelia fovealis, een nieuwe soort voor de Belgische fauna (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Phegea 28: 1.

Gill S. (2013). Greenhouse IPM Pest Alert: European Pepper Moth. University of Maryland Extension. https://extension.umd.edu/learn/greenhouse-ipm-pest-alert-european-pepper-moth (17 December 2014).

Guda CD, Capizzi A, Trematerra P. 1988. Damages on Eustoma grandiflorum (Raf.) Shinn. caused by Duponchelia fovealis (Zeller). Annali dell'Istituto Sperimentale per la Floricultura 19: 3-11.

Hodges G. December 2014. Personal Communication. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry.

Hoffman K. (July 2010). CDFA Detection Advisory for a Cramid moth: Duponchelia fovealis (Zeller) (Pyraloidea: Crambidae). County of Kern, California. http://www.kernag.com/dept/news/2010/2010-san-diego-duponchelia-fovealis-07-16-2010.pdf (29 September 2011).

Ingerson-Mahar J. (2014). European pepper moth. Plant & Pest Advisory. Rutgers Cooperative Extension. http://plant-pest-advisory.rutgers.edu/european-pepper-moth/ (17 December 2014).

Jackel B, Kummer B, Kurhais M. 1996. Biological control of Duponchelia fovealis Zeller (Lepidoptera, Pyralidae). Mitteilungen aus der Biologishen fur Land und Forstwirtschaft 321: 483.

MacLeod A. 1996. Summary Pest Risk Assessment: Duponchelia fovealis. DEFRA (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs), Central Science Laboratory, Sand Hutton, York, United Kingdom.

Marek J, Bártová E. 1998. Duponchelia fovealis Zeller, 1847, a new pest of glasshouse plants in the Czech Republic. Plant Protection Science 34: 151-152.

Messelink G, Van Wensveen W. 2003. Biocontrol of Duponchelia fovealis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) with soil-dwelling predators in potted plants. Communications in Agriculture and Applied Biological Sciences, Ghent University, 68(4a), pp. 159-165.

Murphy G. (November 2008). An overview of Duponchelia control options. Greenhouse Canada. http://www.greenhousecanada.com/inputs/crop-protection/an-overview-of-duponchelia-control-options-1424

NAPIS Pest Tracker (2014). European pepper moth, Duponchelia fovealis. http://pest.ceris.purdue.edu/pest.php?code=ITBMGZA (17 December 2014).

NAPPO. (November 2010). Thirteen new state detections of Duponchelia fovealis, United States. Phytosanitary Alert System. http://www.pestalert.org/oprDetail.cfm?oprID=466&keyword=Duponchelia%20fovealis (29 September 2011).

Osborne LS. (2011). European pepper moth. Mid-Florida Research and Education Center. http://mrec.ifas.ufl.edu/lso/dupon/ (3 October 2011).

Pijnakker J. 2001. Duponchelia fovealis, le lépidoptère redouté des plantes en pot aux Pays-Bas. Revue Horticole 429: 51-53.

Romeijn G. 1996. Een nieuwe plaag in de kas. Vakblad voor de Bloemisterij 47: 46-47.

Trematerra P. 1990. Morphological aspects of Duponchelia fovealis Zeller (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Redia 73: 41-52.

Unknown. 2006a. Duponchelia alla ribalta. Dall'estero. Colture Protette No. 3, page 14.

Unknown. 2006b. Duponchelia: capitolo secondo. Dall'estero. Colture Protette No. 4, page 24.

White J. (2012). Greenhouse Pest Alert: The European pepper moth, Duponchelia fovealis. http://www2.ca.uky.edu/entomology/entfacts/ef324.asp (17 December 2014).

Zandigiacimo P, Buian FM. 2007. Duponchelia fovealis: Un Lepidopterro Crambide Dannoso alle Colture Floricole. Notiziario ERSA, 20: 3-5.

Zimmermann O. 2004. Use of Trichpgramma wasps in Germany; Present status of research and commercial application of egg parasitoids against lepidopterous pests for crop. Gesunde Pflanzen 56: 157-166.