The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

Culiseta melanura (Coquillett 1902) is a species of mosquito that is native to the forested regions of eastern North America. The name “melanura” means “dark-colored tail,” which is indicative of the overall dark coloration of the abdomen of this mosquito species (Figure 1). Culiseta melanura is one of just a few mosquito species in the eastern USA that overwinters in the larval stage. Most mosquito species in this region overwinter as either adults or eggs. Culiseta melanura is considered the most important vector in the transmission cycle of eastern equine encephalitis virus, a virus that can cause severe disease in humans and domesticated animals (Cupp et al. 2003).

Credit: Nathan D. Burkett-Cadena, UF/IFAS

Synonymy

Culex melanurus Coquillett (1902)

From the Integrated Taxonomic Information System and International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (2010).

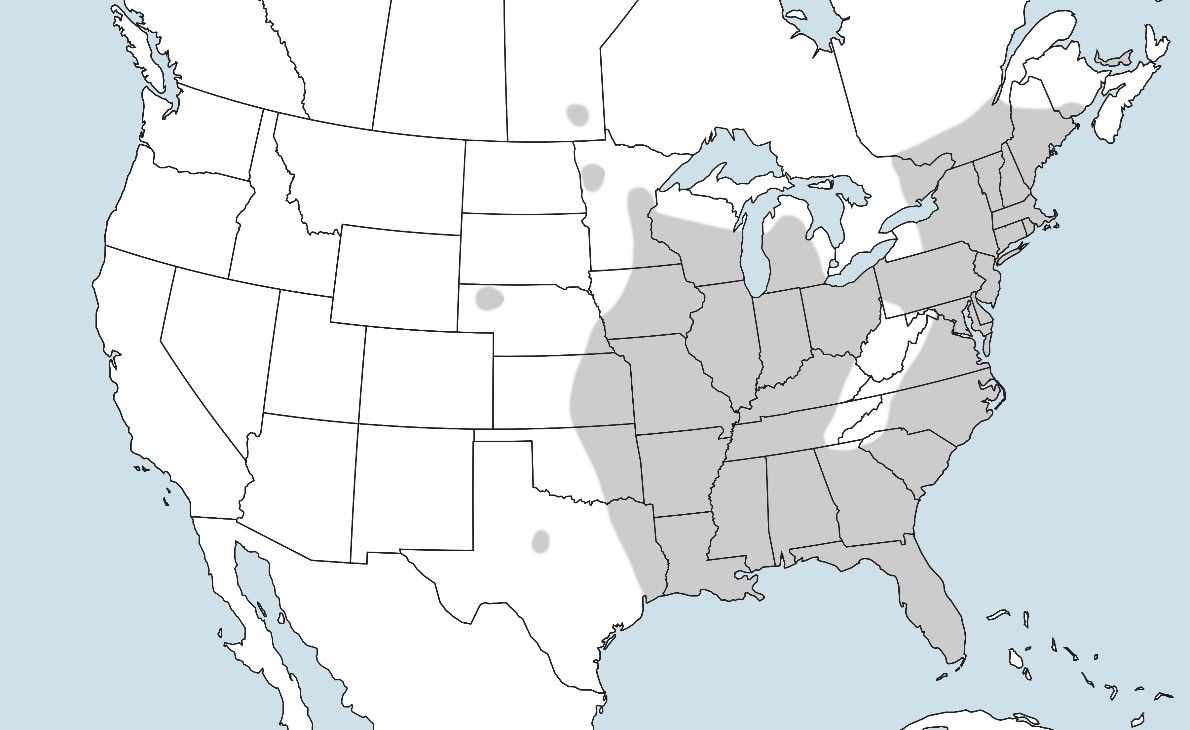

Distribution

Culiseta melanura is primarily found in lowland freshwater swamp habitats of eastern North America, outside of upland Appalachia. It has been recorded from Maine, southern Quebec, and the Great Lakes region in the north, south to Florida, and as far west as eastern Texas (Figure 2; Crans and Mahmood 1998). In Florida, Culiseta melanura is most abundant in the northern half of the state, becoming less common in the southern portion of the peninsula. Culiseta melanura is found as far south as the state of Nuevo León, northeastern Mexico, where larvae were collected the first time in 2001 (Ortega-Morales et al. 2009).

Credit: Nathan D. Burkett-Cadena, UF/IFAS

Description

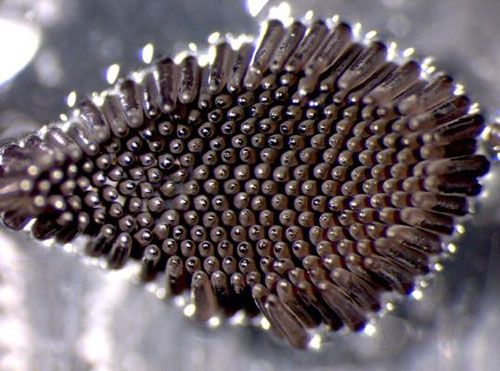

Eggs

The eggs of Culiseta melanura are rather long (about 0.84 mm [0.033 in] in length) (Mattingly 1972) and narrow, and laid on the water's surface in floating clusters. Each floating egg cluster (often called an egg raft) consists of approximately 100 eggs and is the product of a digested blood meal, so each time a female bites she can produce a large number of eggs. The egg rafts are bowl-shaped, and 2.0 to 2.5 mm (0.08 to 0.1 in) in diameter (Figure 3). Culiseta eggs resemble the eggs of Culex mosquitoes in shape but are usually larger (Clements 1999).

Credit: Deborah Arav and Leon Blaustein, University of Haifa

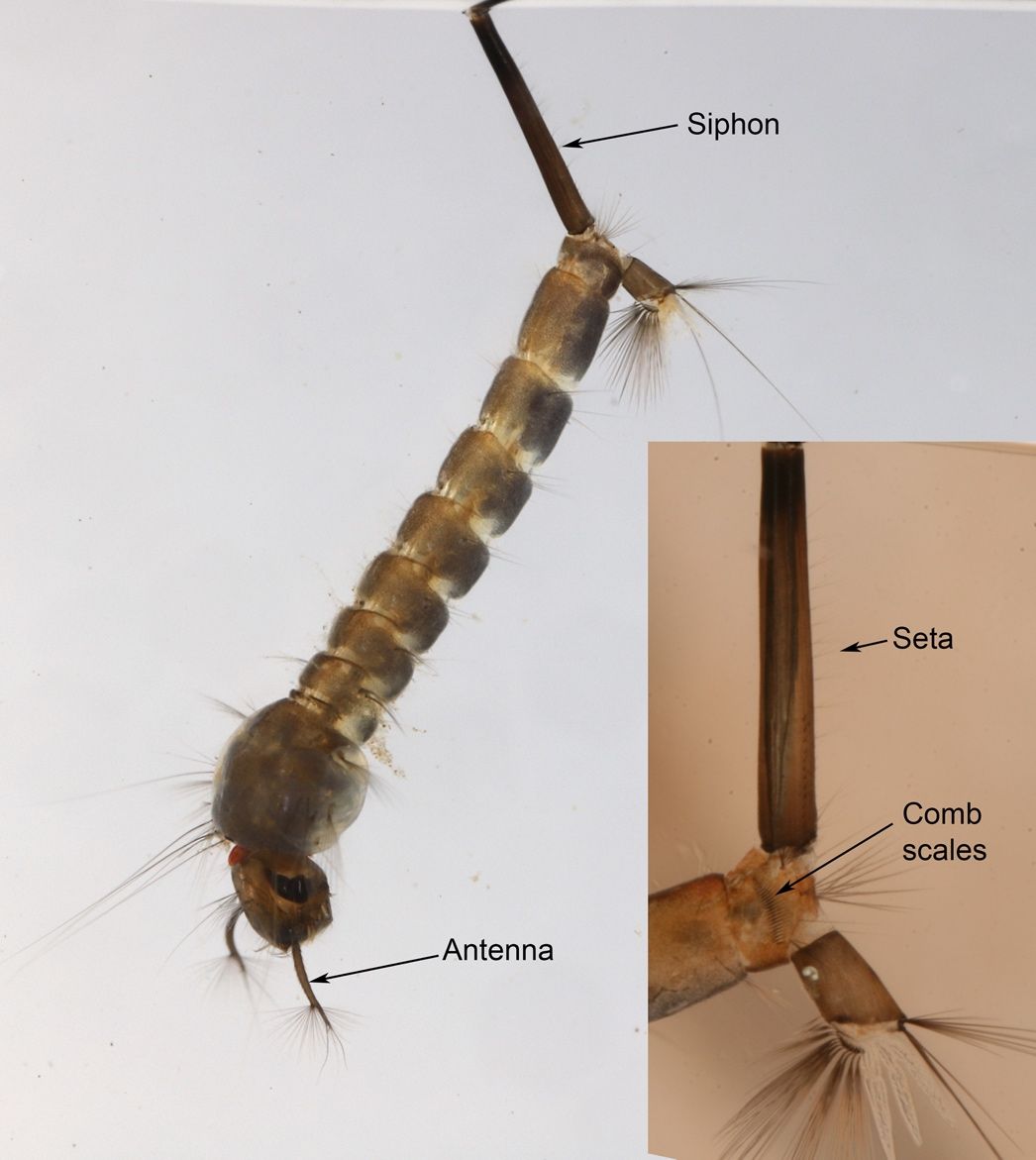

Larvae

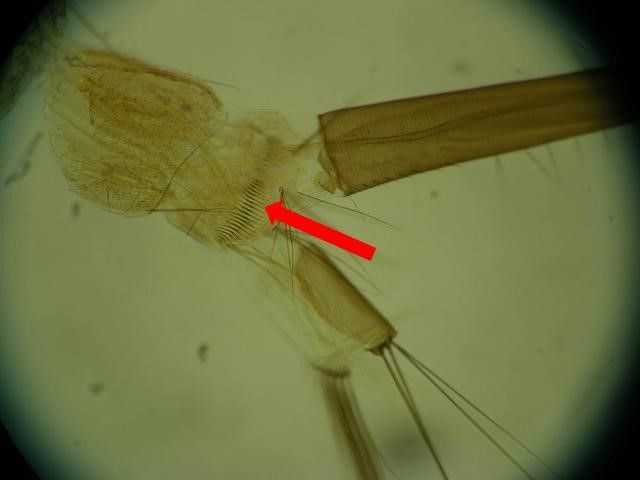

Culiseta melanura larvae are usually dark in color with a very long and narrow siphon (breathing tube) that does not taper much from the base to the tip (Figure 4; Burkett-Cadena 2013). Like other members of the genus, larvae of Culiseta melanura have a pair of setae (hair-like structures) located at the very base of their siphon (Figure 5; Darsie and Ward 2005). This characteristic is only found on larvae of this genus and not other mosquitoes. Other identifying characteristics of Culiseta melanura larvae are a row of 8–14 short and branched setae on the underside of the siphon (Figure 4 inset) and a single row of parallel thorn-like scales located on the eighth segment of the abdomen, that resemble a comb (Figure 6; Darsie and Ward 2005; Crans 2010). The antennae of Culiseta melanura larvae are completely dark, whereas the antennae of many mosquito larvae have a white section.

Credit: Nathan D. Burkett-Cadena, UF/IFAS

Credit: Eva A. Buckner, UF/IFAS

Credit: Eva A. Buckner, UF/IFAS

Pupae

Mosquito pupae are comma-shaped due to the fusion of the head and thorax into a single body region, known as the cephalothorax, connected to the segmented and curved abdomen. Mosquito pupae breathe through two horn-like structures called respiratory trumpets, which are located on either side of the cephalothorax (Figure 7). Culiseta melanura pupae can be recognized by the long setae present on the second segment of its abdomen (Barr 1963). A second seta at the tip of the paddle (the swimming appendage at the end of the abdomen that resembles the tail of a whale or dolphin) distinguishes Culiseta melanura from other Culiseta pupae (Figure 7; Darsie et al. 1962).

Credit: Nathan D. Burkett-Cadena, UF/IFAS

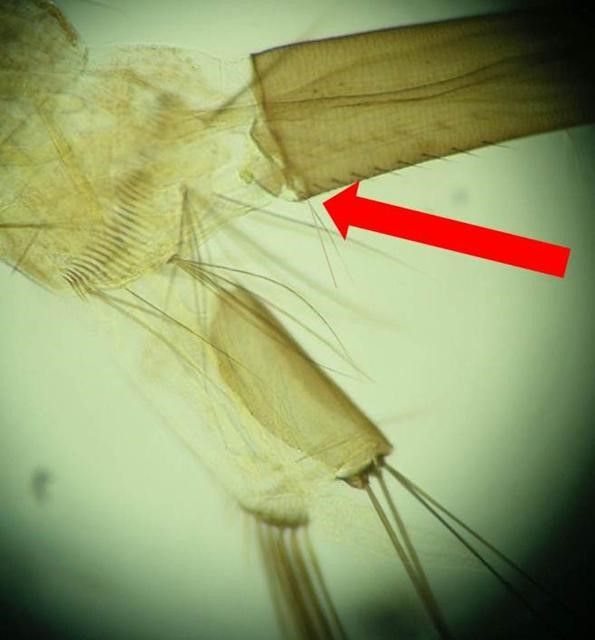

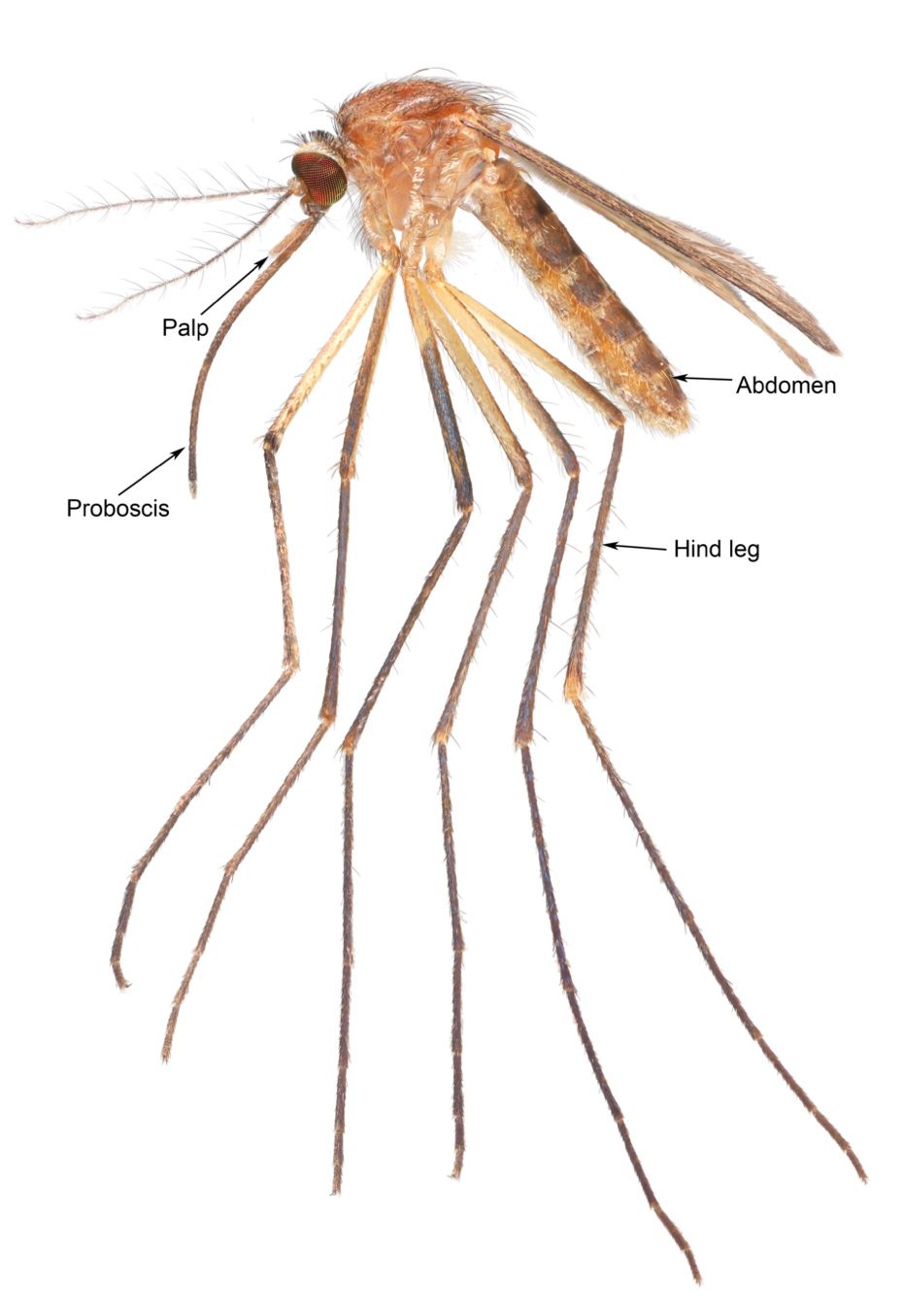

Adults

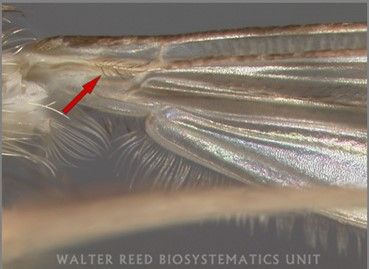

Culiseta melanura is a medium-sized, dark-colored mosquito that generally resembles species of the mosquito genus Culex in overall shape and coloration (King et al. 1960). This species can be recognized by its unusually long, curved, dark-scaled proboscis (biting mouthparts) (Figure 8; King et al. 1960). Its palpi (the paired, finger-shaped structures between the proboscis and eyes) are also dark in color but short. The top of the head is covered with narrow yellow scales and dark scales that stand upright. The top of the thorax is covered in bronze-brown and golden-brown scales (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955). The sides of the thorax are speckled with patches of dull-white scales. The tergites (plates on the upper side of the abdomen) of the abdomen are covered with dark-brown to black scales with a bronze to slightly purple reflection and small patches of dull-white scales on the sides of the base of each segment. Some segments may have narrow yellow-white light bands. The underside of the abdomen is covered in dull white or yellowish scales with scattered dark-colored scales (Burkett-Cadena 2013). The legs are primarily dark-scaled (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955). The base of the subcostal vein on the underside of the wing has a cluster of dark setae that is used for recognizing the genus Culiseta (Figure 9; Carpenter and LaCasse 1955).

Credit: Nathan D. Burkett-Cadena, UF/IFAS

Credit: Judith Stoffer, Walter Reed Biosystematics Unit

Life Cycle

Culiseta melanura has multiple generations per year in the southern part of its range (Horsfall 1955), and adults are active year-round (West et al. 2020a). In the northeastern portion of its range, this species has only two generations per year, probably due to low temperatures during much of the year (Mahmood and Crans 1998). Adult females favor laying their eggs in habitats with acidic water (pH of 5.0 or lower) that are found in dark “crypts” such as spaces created by upturned root masses of trees (Figure 10) that grow in freshwater swamps (cypress, white cedar, or red maple) (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955).

Credit: Nathan D. Burkett-Cadena, UF/IFAS

Larvae of Culiseta melanura typically hatch within two days of eggs being laid (Mattingly 1972). Culiseta melanura larvae are filter feeders and use their brush-like mouthparts to feed on algae, plankton, fungi, bacteria, and other microorganisms suspended in the water column (AMCA 2024). Larval development of Culiseta melanura is relatively slow and often takes two to three months for full development (Armstrong and Andreadis 2022). Larvae hatching in late spring or early summer develop into pupae, whereas those hatching in late summer or early fall overwinter and remain in the larval stage during winter. If temperatures become very cold during the winter, larvae burrow into the sediments in their habitats and can survive several months as third and fourth instar larvae buried in cold muck (Armstrong and Andreadis 2022). Larvae typically pupate in April and emerge as adults by early May in northern states with overlapping generations occurring during summer and two major peaks in adult populations approximately one month apart (Crans and Mahmood 1998; Crans 2004). The pupae remain in the aquatic habitat and do not eat. Temperature affects the length of the pupal stage, which lasts several days (AMCA 2024).

Like other mosquitoes, adults feed on nectar and other plant juices as their source of energy. Females of Culiseta melanura and most other mosquito species require a blood meal in order to nourish and develop their eggs (AMCA 2024). Adult females of Culiseta melanura primarily feed on the blood of songbirds such as the northern cardinal, American robin, and wood thrush (Molaei and Andreadis 2006; Molaei et al. 2006; Bingham et al. 2014; Burkett-Cadena et al. 2015; Miley et al. 2021; West et al. 2020b). However, adult Culiseta melanura females also feed on the blood of reptiles, particularly lizards, in the southern part of their range (Blosser et al. 2017; West et al. 2020b). Lizards are mainly bitten during the warmer months of the year, because lizards sleep on exposed leaves in branches during warm weather but sleep inside crevices (like under loose bark) during cold weather (Blosser et al. 2017). A few studies have shown that Culiseta melanura females will occasionally bite mammals, such as white-tailed deer, raccoons, dogs, cats, and humans (Molaei and Andreadis 2006; Molaei et al. 2006; West et al. 2020b). Females of Culiseta melanura mainly seek out host animals and bite them during the first two hours after sunset but will also bite throughout the night (Nasci and Edman 1981).

Medical and Veterinary Importance

Culiseta melanura is the principal vector of eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEV), a deadly virus endemic to eastern North America (Crans 2010). Culiseta melanura females primarily bite songbirds, which are the natural hosts of EEEV. Humans, horses, and other mammals become infected with EEEV when other mosquito species, such as Aedes canadensis, Coquillettidia perturbans, and Culex erraticus feed on the blood of infected birds and then later bite a mammal, transferring the virus from birds to these hosts (Crans and Schulze 1986; Howard et al. 1988; Cupp et al. 2003). A few studies have demonstrated that Culiseta melanura takes a lesser percentage (5%–25%) of blood meals from mammals (Molaei et al. 2006; Bingham et al. 2014; West et al. 2020b), which suggests that Culiseta melanura can be involved in the transmission of eastern equine encephalitis virus directly to mammals, including humans.

Eastern equine encephalitis virus can cause disease in humans, horses, dogs, and some bird species (Zacks and Paessler 2010). Illness from EEEV infection is most often observed in horses, which are very susceptible to the virus. In humans, EEEV infections rarely result in symptomatic disease, with only 4%–5% of human EEEV infections resulting in disease. When infection with EEEV does cause clinical disease, the symptoms can be very severe. Symptoms include flu-like illness, characterized by fever, chills, body aches, and joint pain, or severe neurologic disease, characterized by fever, headache, vomiting, diarrhea, seizures, behavioral changes, drowsiness, and coma. The severe form of disease more commonly occurs in children under the age of 15, adults over the age of 50, and those with compromised immune systems. Approximately 30% of people who develop severe neurologic disease die. Many survivors suffer from long-lasting neurological problems (CDC 2024). In humans, EEEV symptoms occur generally four to ten days after the bite of an infectious mosquito.

An average of 11 human cases of EEE are reported annually in the United States (CDC 2024), though an outbreak in 2019 led to 38 cases and 12 deaths (Lindsey et al. 2020). Most human EEE cases occur in eastern states. Approximately half (52%) of the total EEEV human cases that were documented from 2003 to 2016 were reported in Massachusetts (24 cases), Florida (18), and New Hampshire (13). The states with the highest average annual incidence (cases per million people) from 2003 to 2016 were New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Vermont, Maine, and Alabama (Lindsey et al. 2018). An average of 1.5 EEE cases per year have been documented in Florida since 1957, with a range of 0–5 cases observed each year (FDOH 2019).

An EEEV vaccine is available for horses but not humans. An average of 44 horses with EEEV were reported each year from 2004 to 2023 in the state of Florida (Day 2024). Eastern equine encephalitis virus can be fatal in up to 90% of unvaccinated horses (Zacks and Paessler 2010). Humans and equines are dead-end hosts for EEEV, meaning mosquitoes do not acquire the virus from them (CDC 2024).

Culiseta melanura is not considered to be an important vector of West Nile virus to humans. However, West Nile virus has been detected in this mosquito species in several studies (Andreadis et al. 2001; Apperson et al. 2004; Godsey et al. 2005; Molaei and Andreadis 2006). Therefore, it is possible that Culiseta melanura may transmit West Nile virus between birds that then serve as part of the mechanism sustaining West Nile virus in a region (Godsey et al. 2005).

Management

The ecology of Culiseta melanura makes its control difficult. Because Culiseta melanura larval habitats are in swamps typically protected by environmental laws, habitat manipulation is generally not possible. Adulticide aerial applications of the pyrethroid sumithrin and the organophosphate naled have resulted in varying degrees of Culiseta melanura control, potentially due to the inability to spray protected areas containing Culiseta melanura habitat (Rathburn et al. 1971; Howard and Oliver 1997; Burtis et al. 2021). Applying larvicide to larval habitats may control immature stages, but reaching crypt-like Culiseta melanura larval habitats can be difficult. For example, while an aerial granular methoprene application was effective in reducing mosquito emergence in open water, it was unable to sufficiently penetrate cryptic Culiseta melanura larval habitats, leading to significantly higher emergence of mosquitoes from inside crypts compared to open water (Burtis et al 2021).

Selected References

AMCA [The American Mosquito Control Association]. Life cycle. https://www.mosquito.org/life-cycle/. [Accessed 24 December 2024].

Andreadis TG, Anderson JF, Vossbrinck CR. 2001. Mosquito surveillance for West Nile virus in Connecticut, 2000: Isolation from Culex pipiens, Cx. restuans, Cx. salinarius, Culiseta melanura. Emerging Infectious Diseases 7: 670–674. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2631746/

Apperson CS, Hassan HK, Harrison BA, Savage HM, Aspen SE, Farajollahi A, Crans W, Daniels TJ, Falco RC, Benedict M, Anderson M, McMillen L, Unnasch TR. 2004. Host feeding patterns of established and potential mosquito vectors of West Nile virus in the eastern United States. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 4: 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1089/153036604773083013

Armstrong PM, Andreadis TG. 2022. Ecology and epidemiology of eastern equine encephalitis virus in the northeastern United States: An historical perspective. Journal of Medical Entomology 59(1): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjab077

Barr RA. 1963. Pupae of the genus Culiseta Felt II: Descriptions and a key to the North American species. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 56: 324–330. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/56.3.324

Bingham AM, Burkett-Cadena ND, Hassan HK, McClure CJ, Unnasch TR. 2014. Field investigations of winter transmission of eastern equine encephalitis virus in Florida. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 91(4): 685–693. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.14-0081

Blosser EM, Lord CC, Stenn T, Acevedo C, Hassan HK, Reeves LE, Unnasch TR, Burkett-Cadena ND. 2017. Environmental drivers of seasonal patterns of host utilization by Culiseta melanura (Diptera: Culicidae) in Florida. Journal of Medical Entomology 54(5): 1365–1374. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjx140

Burkett-Cadena ND. 2013. Mosquitoes of the Southeastern United States. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, AL. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.30347333

Burkett-Cadena ND, Bingham AM, Hunt B, Morse G, Unnasch TR. 2015. Ecology of Culiseta melanura and other mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) from Walton County, FL, during winter period 2013–2014. Journal of Medical Entomology 52(5): 1074–1082. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjv087

Burtis JC, Poggi JD, Duval TB, Bidlack E, Shepard JJ, Matton P, Rossetti R, Harrington LC. 2021. Evaluation of a methoprene aerial application for the control of Culiseta melanura (Diptera: Culicidae) in wetland larval habitats. Journal of Medical Entomology 58(6): 2330–2337. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjab108

Carpenter SJ, LaCasse WJ. 1955. Mosquitoes of North America (North of Mexico). University of California Press, Berkeley, California. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520325098

CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]. 2024. Eastern Equine Encephalitis. https://www.cdc.gov/eastern-equine-encephalitis/site.html. [Accessed 23 December 2024].

Clements AN. 1999. The Biology of Mosquitoes, vol 2, Sensory Reception and Behavior. CABI Publishing, New York. https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851993133.0000

Crans WJ. 2004. A classification system for mosquito life cycles: Life cycle types for mosquitoes of the northeastern United States. Journal of Vector Ecology 29: 1–10.

Crans WJ. 2010. Culiseta melanura (Coquillett). Center for Vector Biology–Rutgers. https://vectorbio.rutgers.edu/outreach/species/sp25.htm. [Accessed 10 June 2016].

Crans WJ, Mahmood F. 1998. Evidence for a bi-voltine life cycle in Culiseta melanura. New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station Publication No. E-40101-01-99.

Crans WJ, Schulze TL. 1986. Evidence incriminating Coquillettidia perturbans (Diptera: Culicidae) as an epizootic vector of eastern equine encephalitis. I. Isolation of EEE virus from Cq. perturbans during an epizootic among horses in New Jersey. Bulletin of the Society for Vector Ecologists 11: 178–184.

Cupp EW, Klingler K, Hassan HK, Vlguers LM, Unnasch TR. 2003. Transmission of eastern equine encephalomyelitis virus in central Alabama. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 68: 495–500. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2003.68.495

Darsie RF Jr, Ward RA. 2005. Identification and Geographical Distribution of the Mosquitoes of North America, North of Mexico. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, Florida.

Darsie RF Jr, Tindall EE, Barr AR. 1962. Description of the pupa of Culiseta melanura. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 3: 167–170.

Day J. 2024. Florida disease activity update newsletter. Volume 4, Issue 20. https://www.clarke.com/florida-arboviral-disease-activity-report-archive/. [Accessed 23 December 2024].

FDOH [Florida Department of Health]. 2019. Florida mosquito-borne disease guidebook. Chapter 2. Overview of select zoonotic mosquito-borne viruses in Florida. https://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/mosquito-borne-diseases/_documents/guidebook-chapter-two.pdf. [Accessed 23 December 2024].

Godsey MS, Blackmore MS, Panella NA, Burkhalter K, Gottfried K, Halsey LA, Rutledge R, Langevin SA, Gates R, Lamonte KM, Lambert A, Lanciotti RS, Blackmore C, Loyless T, Stark L, Oliveri R, Conti L, Komar N. 2005. West Nile virus epizootiology in the southeastern United States, 2001. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 5: 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2005.5.82

Horsfall W. 1955. Mosquitoes, Their Bionomics and Relation to Disease. The Ronald Press Company, New York.

Howard JJ, Morris CD, Emord DE, Grayson MA. 1988. Epizootiology of eastern equine encephalitis virus in upstate New York, USA. VII. Virus surveillance 1978–85, description of 1983 outbreak, and series conclusions. Journal of Medical Entomology 25(6): 501–514. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/25.6.501

Howard JJ, Oliver J. 1997. Impact of naled (Dibrom 14) on the mosquito vectors of eastern equine encephalitis virus. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 13: 315–325.

Integrated Taxonomic Information System. 2010. Culiseta melanura (Coquillett, 1902). https://itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=126443#null [Accessed 10 June 2016].

King W, Bradley G, Smith C, McDuffie W. 1960. A handbook of the mosquitoes of the southern United States. Agriculture Handbook No. 173. United States Department of Agriculture, Washington, D.C.

Lindsey NP, Martin SW, Staples JE, Fischer M. 2020. Notes from the field: Multistate outbreak of eastern equine encephalitis virus—United States, 2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69: 50–51. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6902a4

Lindsey NP, Staples JE, Fischer M. 2018. Eastern equine encephalitis virus in the United States, 2003–2016. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 98(5): 1472–1477. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.17-0927

Mahmood F, Crans WJ. 1998. Effect of temperature on the development of Culiseta melanura (Diptera: Culicidae) and its impact on amplification of eastern equine encephalomyelitis virus in birds. Journal of Medical Entomology 35: 1007–1012. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/35.6.1007

Mattingly PF. 1972. Mosquito eggs XXI Genus Culiseta Felt. Mosquito Systematics Journal 4: 114–127.

Miley KM, Downs J, Burkett-Cadena ND, West RG, Hunt B, Deskins G, Kellner B, Fisher-Grainger S, Unnasch RS, Unnasch TR. 2021. Field analysis of biological factors associated with sites at high and low to moderate risk for eastern equine encephalitis virus winter activity in Florida. Journal of Medical Entomology 58 (6): 2385–2397. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjab066

Molaei G, Andreadis TG. 2006. Identification of avian- and mammalian-derived bloodmeals in Aedes vexans and Culiseta melanura (Diptera: Culicidae) and its implication for West Nile virus transmission in Connecticut, USA. Journal of Medical Entomology 43: 1088–1093. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/43.5.1088

Molaei G, Oliver J, Andreadis TG, Armstrong PM, Howard JJ. 2006. Molecular identification of blood-meal sources in Culiseta melanura and Culiseta morsitans from an endemic focus of eastern equine encephalitis virus in New York. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 75: 1140–1147. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2006.75.1140

Nasci RS, Edman JD. 1981. Vertical and temporal flight activity of the mosquito Culiseta melanura (Diptera: Culicidae) in southeastern Massachusetts. Journal of Medical Entomology 18(6): 501–504. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/18.6.501

Ortega-Morales AI, Elizondo-Quiroga A, Gonzalez-Villarreal A, Siller-Rodriguez QK, Reyes-Villanueva F, Fernandez-Salas I. 2009. First record of Culiseta melanura in Mexico, with additional Mexican records for Aedes sollicitans. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 25: 100–102. https://doi.org/10.2987/08-5774.1

Rathburn, CB Jr, Rogers AJ, Boike AH Jr, Lee RM. 1971. The effectiveness of aerial sprays for the control of adult mosquitoes in Florida as assessed by three methods. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 31: 52–55.

West RG, Mathias D, Day JF, Boohene CK, Unnasch TR, Burkett-Cadena ND. 2020a. Vectorial capacity of Culiseta melanura (Diptera: Culicidae) changes seasonally and is related to epizootic transmission of eastern equine encephalitis virus in central Florida. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 8: 270. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.00270

West RG, Mathias D, Day JF, Acevedo C, Unnasch TR, Burkett-Cadena ND. 2020b. Seasonal changes of host use by Culiseta melanura (Diptera: Culicidae) in central Florida. Journal of Medical Entomology 57(5): 1627–1634. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjaa067

Zacks MA, Paessler S. 2010. Encephalitic alphaviruses. Veterinary Microbiology 140: 281–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.08.023