Introduction

As part of the Savvy Survey Series, this publication provides Extension faculty with an overview of the mixed-mode survey. There are many methods that can be combined for conducting mixed-mode surveys, including face-to-face interviews, telephone interviews, web surveys, and mail questionnaires. This publication focuses specifically on one type of mixed-mode survey that uses both e-mail and postal mail for sending survey invitations, as well as a website and paper questionnaires for collecting responses. Mixed-mode surveys such as this are well suited for conducting needs assessments for program development or follow-up surveys for program evaluation.

A major advantage of mixed-mode surveys is that they allow Extension faculty to include people who lack access to or experience with online surveys to participate via mail, while saving money by reducing the amount spent on postage when e-mail messages and an online questionnaire are used to collect some of the responses. Another advantage is that mixed-mode surveys usually have a higher response rate than surveys conducted solely online (Israel, 2013a; 2013b). In short, mixed-mode surveys are an effective way to collect data (see, for example, Israel, 2011; 2013a; 2013b; Newberry, III and Israel, 2017).

Currently, the University of Florida has a license for Qualtrics survey software, which allows each Extension faculty member to have an account for creating and conducting online surveys. This fact sheet provides guidance for constructing the questionnaire, addressing visual design and formatting considerations, and implementing a mixed-mode survey. Extension faculty who incorporate best practices of questionnaire design and survey procedures will be able to collect many responses and more useful data.

Considerations Specific to Constructing a Mixed-Mode Questionnaire

Since mixed-mode surveys combine e-mail invitations and online questionnaires with postal letters and paper questionnaires, the design of the correspondence and questionnaires requires careful attention so that differences between the online and postal versions are kept to a minimum. This is important because even subtle differences in a questionnaire’s wording or visual presentation can significantly impact the amount and quality of the collected data.

For the paper version of the questionnaire, the space available on a printed page and the weight of the survey package are important considerations (see Savvy Survey #11: Mail-Based Surveys). On the other hand, the online version of the survey must be constructed to match the skill level and experience of the survey population as well as the technology used by the survey software. Qualtrics software, for example, offers a suite of tools for developing a questionnaire, and the designer can include many types of questions and response formats (see Savvy Survey # 6: Writing Items for the Questionnaire). A word of caution: using some of the fancier or more complex question formats should be avoided in order to align the online response process with that of the paper version. Consequently, use of sophisticated skip logic (i.e., survey software commands to skip over questions that do not apply to a particular person) and other features of online survey software should be minimized (see Savvy Survey #13: Online Surveys). Like Qualtrics, other survey applications include many of the same options. It is important to become familiar with the features of the chosen software, especially default settings, in order to avoid unintended problems that adversely affect the usefulness and credibility of the data.

As discussed in Savvy Survey #5: The Process of Developing Survey Questions, a logic model can be very helpful in identifying and selecting high-priority questions to include in the survey.

Visual Design and Formatting

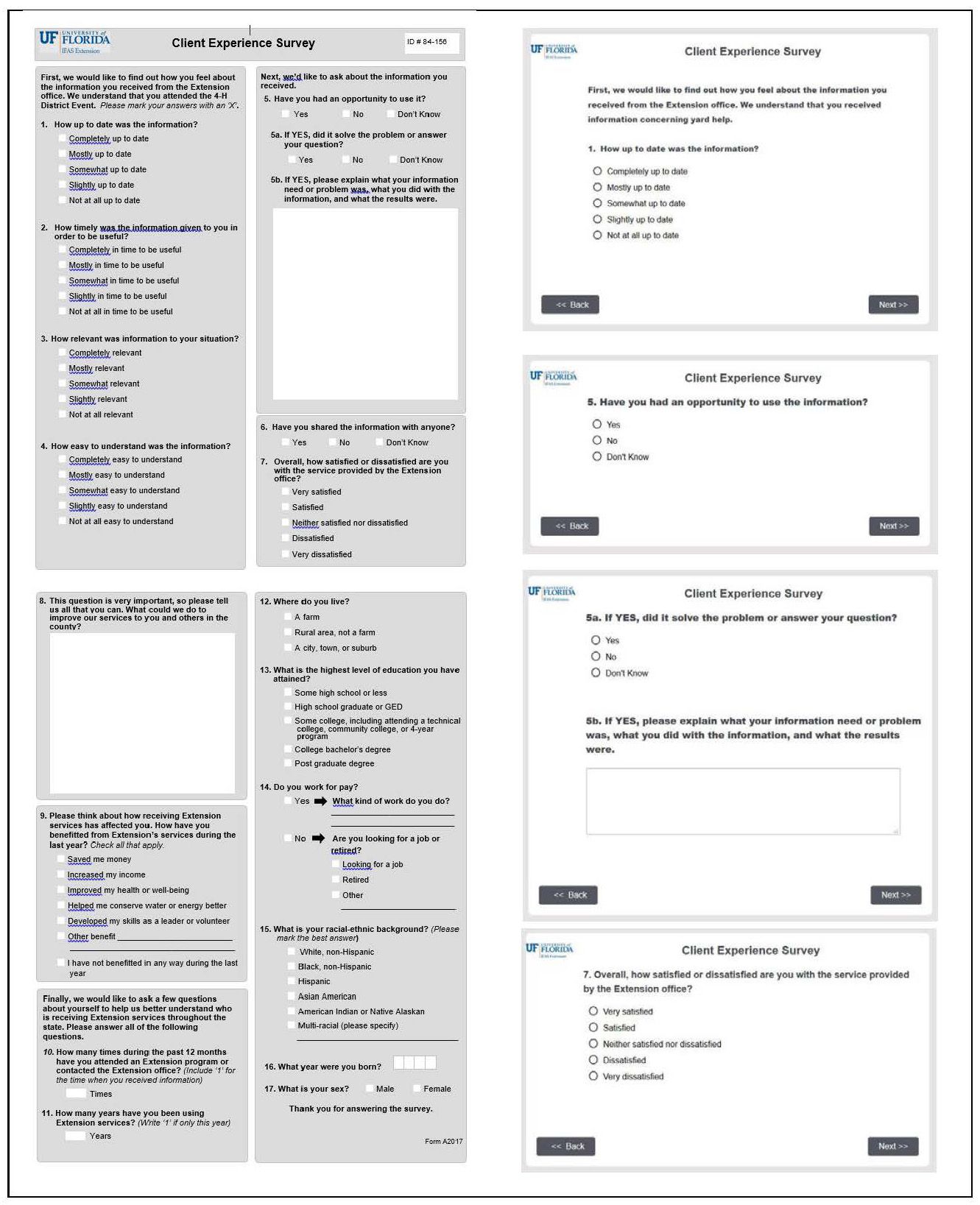

The focus of designing mixed-mode questionnaires is centered on making the online and paper versions appear as similar as possible. Survey researchers call this a “unified mode” design (Dillman, Smyth, and Christian, 2014). This can be challenging because paper surveys utilize a portrait orientation while online surveys usually display questions in a landscape orientation on a desktop or laptop computer. Consequently, the online version of the questionnaire typically uses one question per screen or a gridded set of items on a single screen (Figure 1). In addition, surveys on smartphones are usually seen in portrait orientation because of the way people hold the phone and the screen size can affect how questions are displayed. Note the paper version of the questionnaire in Figure 1 uses shaded areas on the printed page, separated by white outlines, to mimic the screen-by-screen construction of the online version.

Credit: UF/IFAS

The appearance of individual questions, as well as the entire questionnaire, can impact whether and how people answer the survey (Dillman et al., 2014). A good design provides cues to a respondent on how to navigate from one question to another and what kind of information the survey designer is looking for. For example, the size of the answer space for the question "What could we do to improve our services to you and others in the county?" tells a respondent how much to write (a larger space encourages people to write more than a smaller space; see Israel, 2010). Qualtrics, for example, enables survey designers to specify how much space to include (e.g., a single line of text, multi-line essay space, etc.).

A "clean" design that clearly and consistently indicates where the question starts and where the associated answer choices are helps a respondent answer the questions accurately. In Figure 1, several screens of the online survey illustrate constructing the questionnaire with a consistent format, including a header at the top (with the logo and survey title) and navigation buttons in the bottom center area of the screen. There is little extra wording or graphics to distract the respondent.

For more detailed information about writing items or for formatting a questionnaire, see Savvy Survey #6a–d and #7 of the series.

Implementing a Mixed-Mode Survey

Preparation

Getting ready to conduct a mixed-mode survey involves several steps.

Step 1: Prepare the correspondence that will be used in the survey process.

There are several options for sending e-mail or mail invitations to the survey. For surveys that emphasize using e-mail and the online questionnaire, the initial contact should include the link to the website hosting the survey. This recommendation is due to the nature of e-mail messages: they are easily discarded and quickly buried in a person's inbox. Follow-up contacts using this strategy will continue with several e-mail invitations and finish with one or two postal invitations.

Each e-mail and postal message should be carefully worded using the principles of social exchange theory (Dillman et al., 2014) to encourage people to complete the survey. Briefly, social exchange theory asserts that people will be more likely to respond when the benefits (e.g., importance, salience, prestige, usefulness) outweigh the costs (e.g., time, effort, difficulty) and they trust those sending the survey to deliver the benefits. In practice, the e-mail message should discuss how the respondent will benefit, why his or her response is important, and steps taken to reduce costs (i.e., providing a link to access the survey).

Figures 2–6 in Appendix A illustrate a series of messages, with each one tailored to play a specific role in the survey process. In addition, the correspondence should provide all of the information needed for a person to make an informed decision to participate in the survey, including, for example, the amount of time it will take to complete. It is a best practice (and may be required) to have the questionnaire and letters reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) to ensure compliance with regulations for conducting research on human subjects. Note that mixed-mode strategies that use a different sequence of postal and e-mail contacts, as discussed below, will also have the letters worded in a manner that fits the mode and step in the process.

When preparing the correspondence, consider how to personalize it. Research shows that personalization has a small but significant effect on increasing response rates (Dillman et al., 2014). Personalization helps connect the respondent to the survey. This can be done by using individual names of clients in contact messages (e.g., Dear Joe Client) or by a group name with which clients identify (e.g., Dear Jackson County Cattlemen). Although including logos or images might help personalize e-mails to a group, some people continue to use e-mail applications without HTML formatting (which is required to display the graphics). Consequently, e-mail messages should limit the use of logos and images. Finally, draft a simple subject line to use with the e-mail messages (e.g., UF/IFAS Extension Client Experience Survey).

Step 2: Develop an e-mail list with names, e-mail addresses, postal addresses, and other relevant information.

Spreadsheet programs, such as Microsoft® Excel, are useful for organizing the information and keeping track of which people respond and which do not. Table 1 illustrates a spreadsheet list, which includes a column listing the response status and one recording the date that a completed questionnaire is received. In addition, data in a spreadsheet can be used in a mail merge to personalize both e-mail and mail messages by inserting names and other information.

Step 3: Test the survey.

The third step is to test (and re-test) the online survey, making sure that questions are displayed properly, they are shown in the right order, and questions are skipped when they should be. In addition, it is important to test the e-mail distribution procedures by sending an invitation to your own and a colleague's e-mail address (it is embarrassing to have to send out corrected links to the survey, etc.).

Sending Survey Invitations

Contact procedures should be tailored to the situation, as recommended by Dillman et al. (2014) Tailored Design Survey Method. Table 2 shows several examples of contact procedures for a mail and e-mail mixed-mode survey. A best practice is to use multiple contacts to obtain a high response rate and minimize the risk of nonresponse bias.

The sequence of contacts can be tailored to fit one's budget and desire to emphasize online responses.

- Option 1: E-mail Augmentation is designed to collect a large majority of the responses by postal mail. This option also provides an opportunity for people who prefer to complete the survey online by sending an e-mail invitation that is scheduled to arrive shortly after the mailed survey packet (Israel, 2013a).

- Option 2: E-mail Preference can be used with populations who may be unfamiliar with Extension (and reluctant to respond to a cold contact via e-mail). The postal pre-letter can help to introduce the survey and encourage people to respond to the two e-mail invitations. The final two contacts might be sent by postal mail because a number of studies have shown that a postal follow-up with a paper questionnaire results in a large number of completed surveys (Israel, 2013a; 2013b; Millar and Dillman, 2011; Messer and Dillman, 2011; Newberry, III and Israel, 2017).

- Option 3: E-mail Emphasis starts with three e-mail invitations to maximize online responses and minimize postage costs. Because of the findings from the previously cited studies, sending one or two replacement questionnaires by postal mail is highly recommended for this option.

Because the population and timing of the invitations will vary with each option, the letters and e-mail messages should be tailored to the specific role in the sequence. For example, the e-mail message in Option 1 should emphasize the convenience and opportunity to complete the survey online instead of using the paper questionnaire, while the initial email for option 3 would use a similar introduction as that for an e-mail-only survey.

There are several methods for sending e-mail invitations with the Qualtrics survey software. These options are outlined in Table 3.

These options vary in complexity and the amount of faculty control, with the first having the least and the last having the most complexity and control. When using the second option (the Qualtrics internal mailing tool), it is important to recognize that the software reports the number of e-mail invitations sent and, recently, it also reports the number of e-mails that "bounce" or fail to be delivered. One advantage of the third option—using your own e-mail software—is that bounced and delayed e-mail messages can be identified and more easily addressed.

In Summary

This publication in the Savvy Survey Series has focused on procedures for constructing a mixed-mode questionnaire and implementing the survey. It noted that a population's access and experience, software capabilities, and screen/paper compatibility are important considerations in the construction of the questionnaire. In addition, attending to the visual design and formatting of the online and paper questionnaires to minimize differences was emphasized as a critical step in the process. Finally, steps in getting prepared and for sending a sequence of e-mail and postal invitations for completing the survey were discussed. Using multiple contacts in each mode also was emphasized as a best practice for mixed-mode surveys. Using a mixed-mode survey is a way for Extension faculty to collect data from more people and reduce the risk of bias while keeping costs within the available budget.

References

Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method. (4th ed.) Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

Israel, G. D. (2010). Effects of answer space size on responses to open-ended questions in mail surveys. Journal of Official Statistics, 26(2), 271-285. Available at: https://www.scb.se/contentassets/ff271eeeca694f47ae99b942de61df83/effects-of-answer-space-size-on-responses-to-open-ended-questions-in-mail-surveys.pdf.

Israel, G. D. (2011). Strategies for Obtaining Survey Responses from Extension Clients: Exploring the Role of E- mail Requests. Journal of Extension [on-line], 49(3), Article 3FEA7. Available at: https://archives.joe.org/joe/2011june/a7.php.

1. Israel, G. D. (2013a). Combining mail and e-mail contacts to facilitate participation in mixed-mode surveys. Social Science Computer Review, 31(3) 346-358. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439312464942.

Israel, G. D. (2013b). Using Mixed-mode Contacts in Client Surveys: Getting More Bang for Your Buck. Journal of Extension, 51(3), Article 3FEA1. Available at: https://archives.joe.org/joe/2013june/a1.php.

Messer, B. L., & Dillman, D. A. (2011). Surveying the general public over the Internet using address-based sampling and mail contact procedures. Public Opinion Quarterly, 75(3), 429-457. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfr021.

Millar, M. M., & Dillman, D. A. (2011). Improving response to Web and mixed-mode surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 75,(2), 249-269. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfr003.

Newberry, III, M. G., & Israel, G. D. (2017). Comparing two web/mail mixed-mode contact protocols to a unimode mail survey. Field Methods. 29(3), 281-298. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X17693804.

Appendix A.

Credit: UF/IFAS

Credit: UF/IFAS

Credit: UF/IFAS

Credit: UF/IFAS

Credit: UF/IFAS

Table 1. Example of a spreadsheet file with contact information for mailing and record keeping.