Purpose and Target Audience

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) are soil microorganisms that form symbiotic relationships with approximately 80%–90% of vascular plant families. Most crops are dependent on AMF to facilitate the uptake of nutrients, especially phosphorus and nitrogen, thus these fungi make significant contributions to crop production. However, this fungal group is highly sensitive to environmental stressors and management practices, such as intensive tillage and the application of synthetic fertilizers and fungicides. This publication provides general knowledge to growers and the public on the biology and ecological functions of AMF. Understanding how AMF interact with crops and knowing their benefits may raise awareness about this resource and encourage growers to consider AMF when managing their farms. Moreover, we aim to improve the public's knowledge of the role AMF play in agricultural ecosystems.

Introduction

More than 90% of terrestrial plants form symbiotic associations with mycorrhizal fungi (Chen et al. 2017; Begum et al. 2019). Mycorrhizal fungi contribute to nutrient cycling, ecosystem diversity, and the changes and interactions within plant communities over time (Hage-Ahmed et al. 2018; Birhane et al. 2012). These fungi have the ability to supply essential nutrients to plants more efficiently than plants can by themselves. Therefore, incorporating mycorrhizal fungi into agricultural practices has the potential to decrease chemical inputs, improve soil health, and increase crop yield. In this publication, we delve into the world of mycorrhizal fungi, focusing on the biological and ecological roles of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and their associations within the environment.

Biology of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi

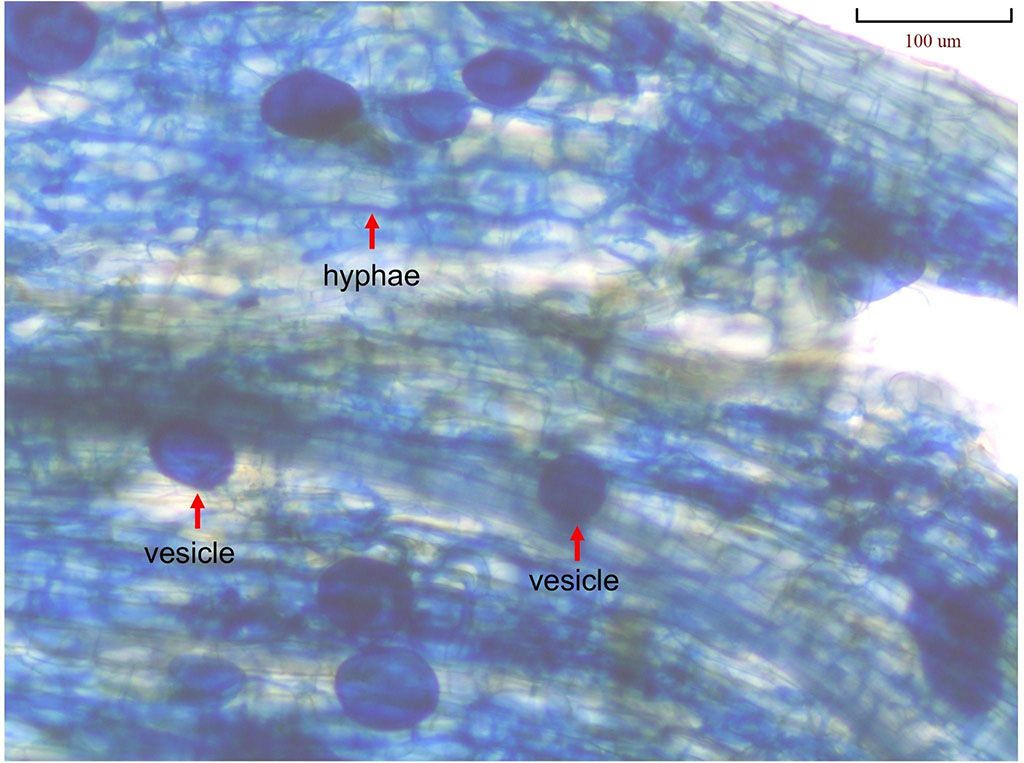

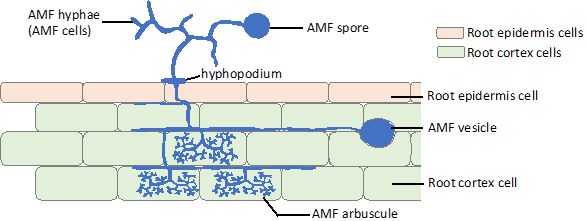

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, of the phylum Glomeromycota, have been studied extensively for their ability to enhance plant growth, improve nutrient uptake, and protect against biotic and abiotic stressors (Figueiredo et al. 2021). Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi complete part of their life cycle within their host (i.e., the plant) without damaging it or causing disease, which is why AMF are referred to as plant symbionts. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi-plant symbiosis is a natural interaction within the plant roots where the exchange of energy, nutrients, and water happens between AMF structures (hyphae, arbuscules, and vesicles; Figure 1) and root cells. Over 80% of terrestrial plant species form AMF associations, which make up the symbiotic fungal hyphae network connecting plant roots and fungi (Giovanetti et al. 2006). Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi are more prevalent in warmer environments such as the tropics (Figueiredo et al. 2021). However, AMF can also be found where terrestrial plants grow in harsh environments, such as the Arctic (Rasmussen et al. 2022).

Credit: Kaile Zhang, UF/IFAS

The Biological Interaction Between AMF and Their Plant Hosts: From Their Initial Meeting to Nutrient Exchange

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi survive in the soil as spores or hyphal fragments that germinate under suitable conditions, enabling them to colonize the root cells of their plant hosts and perform nutrient exchange (Figure 2). There are two main stages of AMF-plant symbiosis: the pre-symbiotic phase and active symbiosis. During the pre-symbiotic phase, fungal spores germinate, the germ tube elongates, the hyphae branch, and contact is initiated with a plant host. In this phase, germinating spores have a short window of opportunity to colonize a plant; otherwise, they will die. This window may last from a few days to several weeks before spore growth stops (Hildebrandt et al. 2002). Fungal spores, much like plant seeds, contain a reserve of nutrients that they utilize for initial growth. To continue the growth cycle, spores must contact plant roots or root exudates in the soil. These exudates act as chemical cues that can signal the presence of a potential host plant and provide the necessary resources for their growth. Concurrently, AMF can emit chemical signals to facilitate the sensing and approaching of host plants. Therefore, it is crucial to avoid chemical treatments, such as fungicides or heavy inorganic fertilizers, during this time, as these treatments will hinder AMF colonization and persistence in the field (Hage-Ahmed et al. 2018). Once a spore finds a plant root, hyphae (Figures 1 and 2) emerge from the spore and form a specialized structure that attaches to the root surface cells and then colonizes the root cortex cells (Figure 2; Bonfante and Genre 2010).

The second stage, active symbiosis, occurs inside the roots when other fungal structures, including vesicles and arbuscules, are formed. Arbuscules, which look like branching tree-shaped structures, are the interface for nutrient exchange between fungi and plant hosts (Nara 2006). They typically form one to three days after initial host contact and degenerate within three to five days, requiring continual replacement (Luginbuehl and Oldroyd 2017; Alexander et al. 1988). Nutrient exchange between mycorrhizal fungi and host plants occurs within the plant cells that are penetrated by AMF arbuscules, where plants deliver approximately 20% of their sugars to the fungal cells (Wang et al. 2017). The nutrient exchange between arbuscules and plants is important for regulating soil and plant nutrients, therefore significantly influencing ecosystem processes, such as plant productivity (van Der Heijden et al. 1998).

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi produce a variety of enzymes useful for transferring nutrients from the soil to other hyphae (Ohirogge and Jaworski 1997). These nutrients — phosphorus (P), inorganic nitrogen (N), sulfur (S), potassium (K), copper (Cu), and iron (Fe) — are initially acquired by the hyphae of AMF as they extend into the soil (Garg and Chandel 2011). For example, researchers found significantly higher P concentrations in the leaves and roots of AMF-inoculated cotton compared to non-inoculated controls (Gao et al. 2020). In lettuce, a diverse mixture of mycorrhizal fungi improved zinc (Zn) accumulation, Cu concentration, and antioxidant levels (Baslam et al. 2011). Moreover, AMF are able to regulate the uptake of elements such as sodium and chlorine, which can be toxic to plant growth when present in high concentrations (Begum et al. 2019).

Credit: Hui-Ling Liao, UF/IFAS

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi can also improve soil structure by producing glomalin (Tang et al. 2022). Glomalin is a strong glue-like substance that binds soil particles together to help form aggregates, which make channels in the soil for root exploration and water movement. By searching outside the area around roots where nutrients and water are limited and by increasing the root surface area, AMF can increase nutrient transport to their hosts (Begum et al. 2019; Chen et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2017).

The Role of AMF in Plant Defense and Adaptation to Abiotic Stress

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi can enhance plant defenses by changing the type and amount of compounds released by the roots. Some of these compounds can deter parasitic nematodes and may attract their microbial predators (Jung et al. 2012). In addition, AMF-inoculated plants may have enhanced plant defense responses against soil-borne pathogenic fungi and bacteria and parasitic nematodes that cause infestations and diseases such as Fusarium wilt, root or shoot rot, and Verticillium wilt (Jung et al. 2012; Hashem et al. 2021; Villani et al. 2021).

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi can apply diverse strategies and mechanisms to handle environmental stressors, such as warming/cold, flooding/drought, and salt or nutrient imbalances. For example, AMF species Rhizophagus irregularis and Glomus mosseae assist plants with heavy metal toxicity in soils (Punamiya et al. 2010). These mycorrhizae can immobilize heavy metals in the cell walls and vacuoles. They may also chelate some metals (Punamiya et al. 2010), reducing the availability and toxicity of these metals to plants.

In addition to their ability to mitigate heavy metal toxicity, AMF play a crucial role in alleviating drought stress through different functions that help plants to conserve water during low water conditions. For example, AMF can produce antioxidant chemicals to help protect cells from damage caused by oxidative stress, which occurs when there are too many reactive oxygen species. These reactive oxygen species are by-products of normal cell activities and can trigger cell damage or even cell death if not managed properly (Tang et al. 2022; Mansoor et al. 2022). Furthermore, AMF enhance water use efficiency by supplying additional water to plants during reduced water conditions. Birhane et al. (2012) found that birch seedlings (Betula papyifera) experienced increased leaf area in drought conditions when colonized with AMF.

AMF can also help plants deal with cold-weather stresses. For example, AMF can increase water-holding capacity, protein content, and sugars (Abdel Latef and Chaoxing 2011). The accumulation of sugars during stress helps plants regulate their metabolism and produce defense compounds as well as water-conserving chemicals. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi can also rebalance the water and homeostasis in plant cells (osmoregulation), which builds organic acids to protect against high salinity (Begum et al. 2019).

The Influence of Agricultural Management on AMF Functionality

In agricultural ecosystems, AMF play a pivotal role in influencing soil health and crop productivity. By enhancing nutrient uptake, improving plant health, and mitigating stress factors, mycorrhizal associations can increase crop yield. This symbiotic relationship is particularly valuable in nutrient-poor soils, where AMF bridges the gap between soil nutrient availability and the nutritional demands of crops. Although the root systems of most agricultural crops host AMF, additional crop studies could help identify optimal management practices for promoting AMF colonization and matching specific AMF species to their corresponding plant species. Table 1 lists representative greenhouse studies or field trials demonstrating the benefits of AMF to specific crops. Studies, such as those in greenhouse or field trials, provide valuable insights into the potential benefits of AMF for specific crops, but they may not cover every crop variety or growing condition. Growers should be cautious about relying solely on these studies for management decisions, as results can vary depending on the crop, location, and environmental factors. It is important to consider these factors, along with local conditions, when deciding whether to use AMF for crop management.

Since using AMF improves the efficiency of nutrient uptake, such as for P and N, the need for inorganic fertilizers could decrease in some systems (Begum et al. 2019; Yang et al. 2004). Reduced inputs would not only enhance the overall soil health but also mitigate agricultural pollution, lessening harm to diverse ecosystems and wildlife species. However, modern industrial agriculture, such as high chemical regimes, repeated tillage, and monocultures, decreases AMF abundance and diversity (Guzman et al. 2021). When AMF developmental stages are interrupted by chemical inputs, AMF colonization and growth can be significantly reduced (Hage-Ahmed et al. 2018). Consequently, agricultural practices should accommodate a healthy spore bank to ensure colonization occurs after chemical exposure. For example, decreased tillage, conservation tillage, seed drills, and crimp rollers are highly recommended to help fungi colonize crop roots more robustly, which in turn will facilitate crop resilience and nutrient transfer (Hage-Ahmed et al. 2018).

Table 1. The representative greenhouse studies or field trials indicating the benefits of AMF to the growth and resilience of specific agricultural crops.

Glossary of Specialized Terms

AMF arbuscules are the site of nutrient exchange located inside plant cells that have a branching, tree-like structure.

AMF vesicles are round, fungal exchange sites located within plant cortical cells formed by AMF.

Antioxidants are substances that help protect our cells from damage.

Fungal hyphae are branching, filamentous structures of the fungus.

Fungal spores are biological particles that enable fungi to reproduce. Their function is similar to seeds in plants.

A germ tube is a tiny thread that emerges from a fungal spore as it begins to grow. This germ tube develops into a hypha, which is a long, thin filament that forms the basic structural unit of a fungus.

Glomalin is a sticky, glue-like substance produced by hyphae and spores of AMF.

Plant cortex cells are unspecialized cells located between the surface cells (epidermis) and the vascular tissues.

Plant epidermis cells are surface cells covering the stems, flowers, fruit, and seeds of plants.

Reactive oxygen species include a variety of reactive, oxidant molecules that can turn on or off different biological functions. They play a role in aging and genetic mutations. They are also capable of degrading organic pollutants.

The rhizosphere is the narrow area surrounding the soil which is influenced directly by root exudates and microorganisms around the roots.

Symbiosis is a mutually beneficial association between two or more different organisms.

References

Abdelhameed, R. E., and R. A. Metwally. 2019. “Alleviation of Cadmium Stress by Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis.” International Journal of Phytoremediation 21 (7): 663–671. https://doi.org/10.1080/15226514.2018.1556584

Abdel Latef, A. A., and H. Chaoxing. 2011. “Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Influence on Growth, Photosynthetic Pigments, Osmotic Adjustment and Oxidative Stress in Tomato Plants Subjected to Low Temperature Stress.” Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 33: 1217–1225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11738-010-0650-3

Ajay, P., and S. Pandey. 2017. “Role of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Plant Growth and Reclamation of Barren Soil with Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Crop.” International Journal of Soil Science 12 (1): 25–31. https://doi.org/10.3923/ijss.2017.25.31

Alexander, T., R. Meier, R. Toth, and H. C. Weber. 1988. “Dynamics of Arbuscule Development and Degeneration in Mycorrhizas of Triticum aestivum L. and Avena sativa L. with Reference to Zea mays L.” New Phytologist 110 (3): 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.1988.tb00273.x

Balliu, A., G. Sallaku, and B. Rewald. 2015. “AMF inoculation enhances growth and improves the nutrient uptake rates of transplanted, salt-stressed tomato seedlings.” Sustainability 7 (12): 15967–15981. https://doi.org/10.3390/su71215799

Baslam, M., I. Garmendia, and N. Goichoechea. 2011. “Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) improved growth and nutritional quality of greenhouse-grown lettuce.” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 59 (10): 5504–5515. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf200501c

Begum, N., C. Qin, M. A. Ahanger, et al. 2019. “Role of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Plant Growth Regulation: Implications in Abiotic Stress Tolerance.” Frontiers in Plant Science 10: 1068. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.01068

Birhane, E., F. Sterck, M. Fetene, F. Bongers, and T. Kuyper. 2012. “Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance photosynthesis, water use efficiency, and growth of frankincense seedlings under pulsed water availability conditions.” Oecologia 169: 895–904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-012-2258-3

Bonfante, P., and A. Genre. 2010. “Mechanisms Underlying Beneficial Plant-Fungus Interactions in Mycorrhizal Symbiosis.” Nature Communications 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1046

Boyer, L. R., P. Brain, X. M. Xu, and P. Jeffries. 2014. “Inoculation of Drought-Stressed Strawberry with a Mixed Inoculum of Two Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi: Effects on Population Dynamics of Fungal Species in Roots and Consequential Plant Tolerance to Water.” Mycorrhiza 25: 215–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-014-0603-6

Calvo-Polanco, M., B. Sanchez-Romera, R. Aroca, et al. 2016. “Exploring the Use of Recombinant Inbred Lines in Combination with Beneficial Microbial Inoculants (AM Fungus and PGPR) to Improve Drought Stress Tolerance in Tomato.” Environmental and Experimental Botany 131: 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2016.06.015

Charoonnart, P., K. Seraypheap, S. Chadchawan, and T. Wangsomboondee. 2016. “Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus improves the yield and quality of Lactuca sativa in an organic farming system.” ScienceAsia 42: 315. https://doi.org/10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2016.42.315

Chen, S., H. Zhao, C. Zou, et al. 2017. “Combined inoculation with multiple arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi improves growth, nutrient uptake and photosynthesis in cucumber seedlings.” Frontiers in Microbiology 8: 2516. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02516

Figueiredo, A. F., J. Boy, and G. Guggenberger. 2021. “Common Mycorrhizae Network: A review of the Theories and Mechanisms Behind Underground Interactions.” Frontiers in Fungal Biology 2: 735299. https://doi.org/10.3389/ffunb.2021.735299

Gao, X., H. Guo, Q. Zhang, et al. 2020. “Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) enhanced the growth, yield, fiber quality and phosphorus regulation in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.).” Scientific Reports 10: 2084. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59180-3

Garg, N., and S. Chandel. 2011. “Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Networks: Process and Functions.” In Sustainable Agriculture, edited by E. Lichtfouse, M. Hamelin, M. Navarrete, and P. Debaeke. Vol. 2. Springer Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0394-0_40

Giovannetti, M., L. Avio, P. Fortuna, E. Pellegrino, C. Sbrana, and P. Strani. 2006. “At the Root of the Wood Wide Web.” Plant Signaling & Behavior 1 (1): 1–5. https://doi.org/10.4161/psb.1.1.2277

Guzman, A., M. Montes, L. Hutchins, et al. 2021. “Crop diversity enriches arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities in an intensive agricultural landscape.” New Phytology 231 (1): 447–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17306

Hage-Ahmed, K., K. Rosner, and S. Steinkellner. 2018. “Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Their Response to Pesticides.” Pest Management Science 75 (3): 583–590. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.5220

Hashem, A., A. Akhter, A. A. Alqarawi, G. Singh, K. F. Almutairi, and E. F. AbdAllah. 2021. “Mycorrhisal Fungi Induced Activation of Tomato Defense System Mitigates Fusarium Wilt Stress.” Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 28 (10): 5442–5420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.07.025

Hijri, M. 2016. “Analysis of a large dataset of mycorrhiza inoculation field trials on potato shows highly significant increases in yield.” Mycorrhiza 26: 209–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-015-0661-4

Hildebrandt, U., K. Janetta, and H. Bothe. 2002. “Towards Growth of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Independent of a Plant Host.” Applied and Environmental Microbiology 68 (4): 1919–1924. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.68.4.1919-1924.2002

Jung, S. C., A. Martinez-Medina, J. A. Lopez-Raez, and M. J. Pozo. 2012. “Mycorrhiza-Induced Resistance and Priming of Plant Defenses.” Journal of Chemical Ecology 38: 651–664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-012-0134-6

Kaur, J., J. Chavana, P. Soti, A. Racelis, and R. Kariyat. 2020. “Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) influences growth and insect community dynamics in Sorghum-sudangrass (Sorghum x drummondii).” Arthropod-Plant Interactions 14: 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11829-020-09747-8

Luginbuehl, L. H., and G. E. D. Oldroyd. 2017. “Understanding the Arbuscule at the Heart of Endomycorrhizal Symbioses in Plants.” Current Biology 27 (17): R952–R963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.06.042

Madhushan, K. W. A., S. C. Karunarathna, D. M. D. Dissanayake, et al. 2023. “Effect of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Lowland Rice Growth and Yield (Oryza sativa L.) Under Different Farming Practices.” Agronomy 13 (11): 2803. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13112803

Mansoor, S., O. Ali Wani, J. K. Lone, et al. 2022. “Reactive Oxygen Species in Plants: From Source to Sink.” Antioxidants 11 (2): 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11020225

Mathur, S., M. P. Sharma, and A. Jajoo. 2018. “Improved Photosynthetic Efficacy of Maize (Zea mays) Plants with Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF) Under High Temperature Stress.” Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 180: 149–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.02.002

Nara, K. 2006. “Ectomycorrhizal Networks and Seedling Establishment During Early Primary Succession.” New Phytologist 169 (1): 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01545.x

Ohirogge, J. B., and J. G. Jaworski. 1997. “Regulation of Fatty Acid Synthesis.” Annual Review of Plant Physiology 48: 109–136. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.109

Ouledali, S., M. Ennajeh, A. Zrig, S. Gianinazzi, and H. Khemira. 2018. “Estimating the Contribution of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi to Drought Tolerance of Potted Olive Trees (Olea europaea).” Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 40: 81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11738-018-2656-1

Pavithra, D., and N. Yapa. 2018. “Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi inoculation enhances drought stress tolerance of plants.” Groundwater for Sustainable Development 7: 490–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsd.2018.03.005

Punamiya, P., R. Datta, D. Sarkar, S. Barber, M. Patel, and P. Da. 2010. “Symbiotic Role of Glomus mosseae in Phytoextraction of Lead in Vetiver Grass Chrysopogon zizanioides L.” Journal of Hazardous Materials 177 (1–3): 465–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.12.056

Rasmussen, P. U., N. Abrego, R. Roslin, et al. 2022. “Elevation and plant species identity jointly shape a diverse arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal community in the high Arctic.” New Phytologist 236 (2): 671–683. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.18342

Regvar, M., K. Vogel-Mikuš, and T. Ševerkar. 2003. “Effect of AMF Inoculum from Field Isolates on the Yield of Green Pepper, Parsley, Carrot, and Tomato.” Folia Geobotanica 38 (2): 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02803154

Tang, H., M. U. Hassan, L. Feng, et al. 2022. “The Critical Role of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi to Improve Drought Tolerance and Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Crops.” Frontiers in Plant Science 13: 919166. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.919166

van Der Heijden, M. G. A., J. Klironomos, M. Ursic, et al. 1998. “Mycorrhizal fungal diversity determines plant biodiversity, ecosystem variability and productivity.” Nature 396: 69–72. https://doi.org/10.1038/23932

Villani, A., F. Tommasi, and C. Paciolla. 2021. “The arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Glomus viscosum improves the tolerance to Verticillium wilt in artichoke by modulating the antioxidant defense systems.” Cells 10 (8). https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10081944

Wang, W., J. Shi, Q. Xie, Y. Jiang, N. Yu, and E. Wang. 2017. “Nutrient Exchange and Regulation in Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis.” Molecular Plant 10 (9): 1147–1158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2017.07.012

Yang, S., F. Li, S. S. Malhi, P. Wang, S. Dongrang, and J. Wang. 2004. “Long-Term Fertilization Effects on Crop Yield and Nitrate Nitrogen Accumulation in Soil in Northwestern China.” Agronomy Journal 96 (4): 1039–1049. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2004.1039

Yooyongwech, S., T. Samphumphuang, R. Tisarum, C. Theerawitaya, and S. Chaum. 2016. “Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) improved water deficit tolerance in two different sweet potato genotypes involves osmotic adjustments via soluble sugar and free proline.” Scientia Horticulturae 198: 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2015.11.002

Zhou, L.-J., Y. Wang Y, M. D. Alqahtani, and Q.-S. Wu. 2023. “Positive Changes in Fruit Quality, Leaf Antioxidant Defense System, and Soil Fertility of Beni-Madonna Tangor Citrus (Citrus nanko × C. amakusa) After Field AMF Inoculation.” Horticulturae 9 (12): 1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9121324

Further Reading

Askari, A., M. R. Ardakani, F. Paknejad, and Y. Hosseini. 2019. “Effects of Mycorrhizal Symbiosis and Seed Priming on Yield and Water Use Efficiency of Sesame Under Drought Stress Conditions.” Scientia Horticulturae 257: 108749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2019.108749

Fellbaum, C. R., J. A. Mensah, A. J. Cloos, et al. 2014. “Fungal nutrient allocation in common mycorrhizal networks is regulated by the carbon source strength of individual host plants.” New Phytologist 203 (2): 646–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12827

Gough, E. C., K. J. Owen, R. S. Zwart, and J. P. Thompson. 2021. “Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi acted synergistically with Bradyrhizobium sp. to improve nodulation, nitrogen fixation, plant growth and seed yield of mung bean (Vigna radiata) but increased the population density of the root-lesion nematode Pratylenchus thornei.” Plant and Soil 465: 431–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-021-05007-7

Maya, M. A., and Y. Matsubara. 2013. “Influence of Arbuscular Mycorrhiza on the Growth and Antioxidative Activity in Cyclamen Under Heat Stress.” Mycorrhiza 23: 381–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-013-0477-z

van Der Heijden, M. G. A., and T. R. Horton. 2009. “Socialism in Soil? The Importance of Mycorrhizal Fungal Networks for Facilitation in Natural Ecosystems.” Journal of Ecology 97 (6): 1139–1150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01570.x

Walder, F., H. Niemann, M. Natarajan, M. F. Lehmann, T. Boller, and A. Wiemken. 2012. “Mycorrhizal Networks: Common Goods of Plants Shared Under Unequal Terms of Trade.” Plant Physiology 159: 789–797. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.112.195727

Zhang, L., M.-X. Wang, L. Hua, L. Yuan, J. G. Huang, and C. Penfold. 2014. “Mobilization of Inorganic Phosphorus from Soils by Ectomycorrhizal Fungi.” Pedosphere 24 (5): 683–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1002-0160(14)60054-0

Zhang, K., R. Tappero, J. Ruytinx, S. Branco, and H.-L. Liao. 2021. “Disentangling the Role of Ectomycorrhizal Fungi in Plant Nutrient Acquisition Along a Zn Gradient Using X-ray Imaging.” Science of the Total Environment 801: 149481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149481

Zhang, K., H. Wang, R. Tappero, et al. 2023. “Ectomycorrhizal fungi enhance pine growth by stimulating iron-dependent mechanisms with trade-offs in symbiotic performance.” New Phytologist 242 (4): 1645–1660. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.19449.

Zhang, W., L. Yu, B. Han, K. Liu, and X. Shao. 2022. “Mycorrhizal inoculation enhances nutrient absorption and induces insect-resistant defense of Elymus nutans.” Frontiers in Plant Science 13: 898969–898969. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.898969

Zhu, X. C., F. B. Song, S. Q. Liu, and T. D. Liu. 2011. “Effects of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus on Photosynthesis and Water Status of Maize Under High Temperature Stress.” Plant and Soil 346: 189–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-011-0809-8