Introduction

Global population growth is significantly increasing the need for freshwater. This vital resource is in great demand yet also short in supply and unevenly distributed (Global Water Intelligence 2024). Despite the abundant water on the Earth's surface, most water bodies are saline, meaning the water contains a high concentration of dissolved salts, unsuitable for human consumption. Seawater generally has a high salinity, around 35,000 mg/L of total dissolved solids (TDS), which refers to the combined content of all inorganic and organic substances present in water as a dissolved form (Kang and Jackson 2016). Brackish water, a term that describes water with salinity levels between 1,000 and 10,000 mg/L, lies between freshwater and seawater in salt concentration. For drinking water, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency recommends a TDS level of 500 mg/L or lower (Benham et al. 2019).

Desalination is the method of removing dissolved salt and other minerals from saline water sources, including but not limited to brackish and seawater. The desalination process has become a crucial way of producing freshwater worldwide. Over 20,000 desalination plants existed worldwide in 2020, with an estimated capacity of 23.8 billion gallons per day (Paup and Peyton 2022). More recent analyses indicate continued growth. According to the International Desalination and Reuse Association (IDRA), the global installed desalination capacity reached approximately 115 million cubic meters per day (about 30.4 billion gallons per day) by the end of 2022, with more than 21,000 desalination facilities in operation worldwide (Global Water Intelligence 2023). This publication is primarily intended for Extension educators, environmental and water resources consultants, and the general public interested in desalination systems and their environmental impacts.

In Florida, desalination plays a key role in addressing the state's growing water demands. With a projected statewide water supply shortfall of approximately 300 million gallons per day (MGD) by 2040 as a result of population growth, desalination is positioned as a viable option for supplementing freshwater supplies (Martel 2023; Haque 2023; Kassis et al. 2023). Florida already leads the United States in desalination capacity, with more than 130 plants in operation, primarily relying on reverse osmosis to treat brackish groundwater and seawater (Aslan et al. 2023).

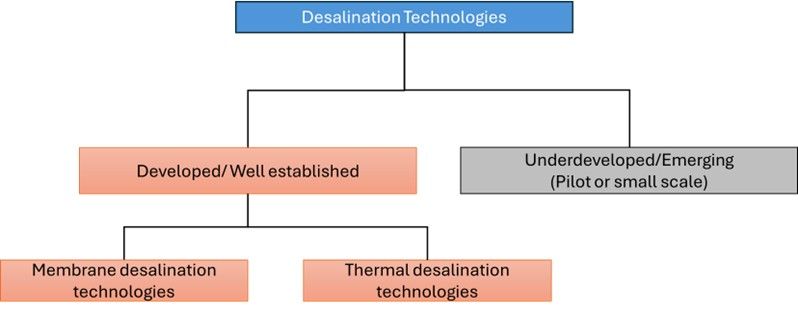

Desalination Technologies

Many technologies are available for the desalination of seawater and brackish groundwater supplies. Depending on their maturity level, desalination technologies can be divided into two categories: developed/well-established and undeveloped/emerging technologies. Developed technologies can be subdivided into thermal desalination and membrane desalination technologies. Over the years, these technologies have been demonstrated to be technically feasible, economically viable, and reliable. Emerging desalination technologies are still in the pilot or small-scale stages of development. For example, forward osmosis (FO), which utilizes natural osmotic pressure differences to draw water through a semipermeable membrane, potentially reduces energy consumption compared to traditional reverse osmosis. Pilot studies have demonstrated FO's effectiveness in desalinating high-salinity brines (Cath et al. 2006). Another example is capacitive deionization (CDI), which employs electrostatic forces to remove ions from brackish water. Recent pilot plant studies have shown CDI's potential for energy-efficient desalination, producing demineralized water with lower energy requirements (Ahmed and Tewari 2018). In terms of energy consumption and feedwater quality, emerging technologies have outperformed currently used technologies.

Thermal Desalination Process

Thermal desalination was the first technology employed in the early era of desalination during the 1950s through the 1970s (Van der Bruggen and Vandecasteele 2002). Thermal desalination is sometimes known as phase-change desalination since the process transitions water from liquid to vapor and then reversely. The thermal desalination process applies energy to the saline water, generating steam that is then collected and condensed into pure water. Due to the expensive nature of this technology, using it is preferable when the salinity content of the water to be treated is high. It is also favorable when co-located with a power plant. Some commonly known thermal-based technologies include multi-stage flash (MSF), multi-effect distillation (MED), and vapor compression distillation (Beltrán and Koo-Oshima 2006).

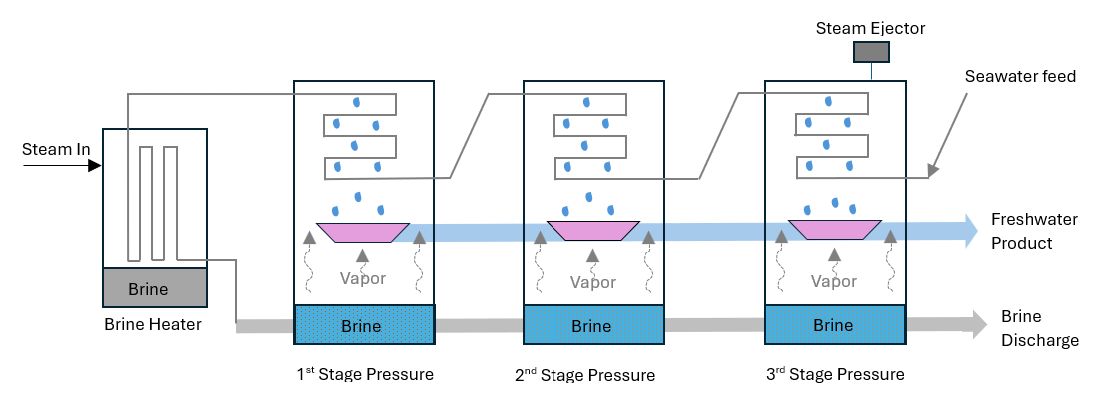

Multi-Stage Flash Distillation (MSF): Figure 2 illustrates the schematic flow chart of the MSF process. It is mainly employed for desalinating seawater. This process relies on the principles of water evaporation and condensation.

The MSF consists of various stages: the feed water preheats, the pressure reduces in stages with low temperature, a fraction of saline water evaporates (flashes), and the remaining water continues rushing in stages. The vapor in each stage collects and condenses to form fresh water. Each successive stage of the MSF unit operates at a lower pressure to maximize water recovery (Assad et al. 2022). The associated advantage of the MSF distillation method is the production of quality water that has less than 10 mg/L TDS. The salinity of the feed water does not significantly influence the cost of the MSF process. The disadvantages of using the MSF are the costs of installation and operation, coupled with the requirement for a high level of technical knowledge. Another concern is the corrosion and scaling of the evaporator component (Islam et al. 2018).

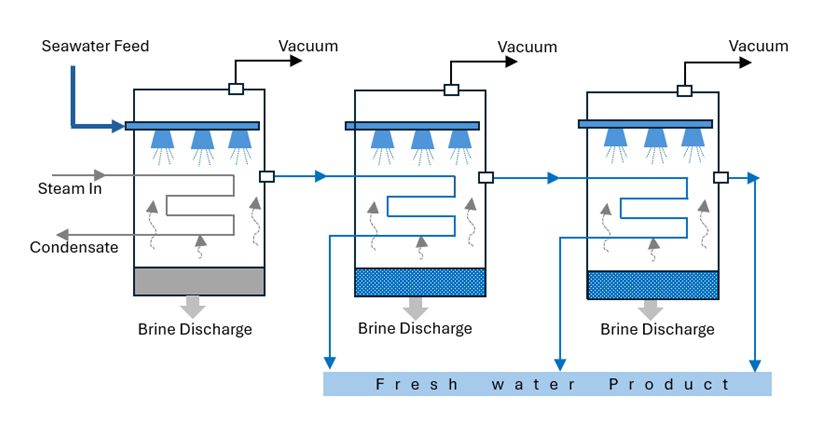

Multi-Effect Desalination (MED): This process also requires the application of evaporation and condensation at a decreased ambient pressure. In the MED method, a series of evaporator effects produces water at progressively lower pressures. Figure 3 shows the schematic flow chart of the MED process. It is mainly used for seawater desalination. With decreased pressure, water boils at a lower temperature, so the first vessel vapor serves as a heating medium for the second and so on. The vapor from each stage condenses in the next successive stage, thereby giving up its heat to drive more evaporation (Assad et al. 2022).

Vapor Compression (VC): Improvements to MED involve adding vapor compression (VC) to increase energy efficiency. It involves evaporating the feed water, compressing the resulting vapor, and then employing the pressurized vapor as a heat source to evaporate additional feed water. Either a mechanical compressor or a steam ejector can carry out the vapor compression. VC units are usually small in capacity (Islam et al. 2018).

Membrane Desalination Process

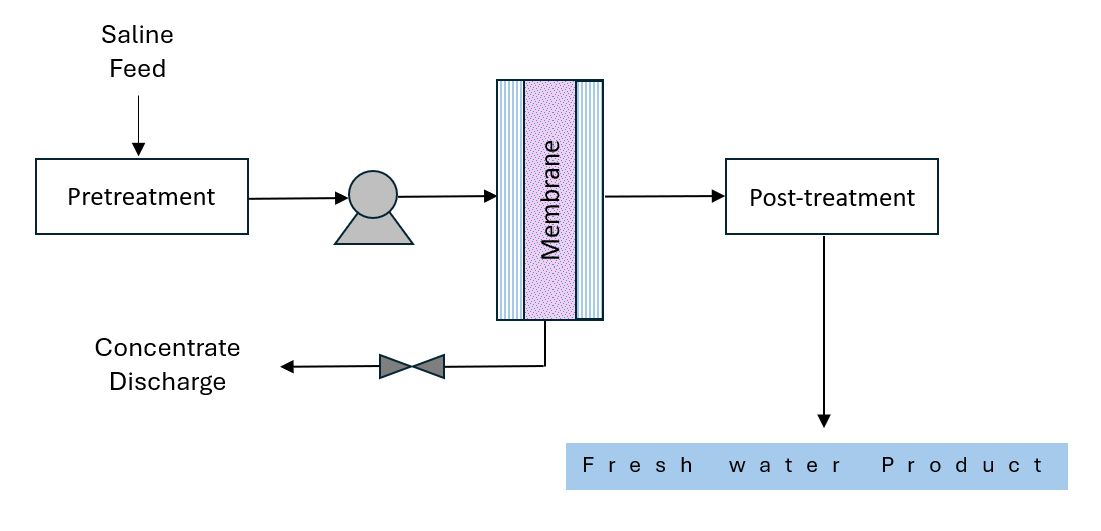

Another category of desalination methods is membrane-based technology, which allows specific components to pass through a membrane while blocking others. Membrane technology separates these various components of saline water by applying pressure gradients, temperature gradients, concentration gradients, or electrical potential gradients. The most frequently used membrane-based technologies are reverse osmosis (RO), electrodialysis (ED), and, in some cases, forward osmosis (FO) (Islam et al. 2018). Using solar energy can also produce water vapor from saline water. Then, the vapor condenses on a cooler surface to collect potable water. The use of this method is minimal since it usually collects a small quantity of desalinated water (Beltrán and Koo-Oshima 2006).

Reverse Osmosis (RO): Recently, the most common method for desalination in the world is reverse osmosis, as shown in Figure 4. After pretreating the saline, the RO process uses pressure as the driving force to push saline water through a semi-permeable membrane into a product water stream and a concentrated brine stream. The application of pressure on the membrane systems facilitates the passage of the water molecules, pushing freshwater through but leaving salt and other impurities behind. Reverse osmosis is a great, less expensive technology that uses electricity rather than heat to power the pumps in the plant. Pretreatment is a crucial part of the RO process as it protects the membrane surfaces from corroding and fouling, while also ensuring the efficiency of the system (Assad et al. 2022).

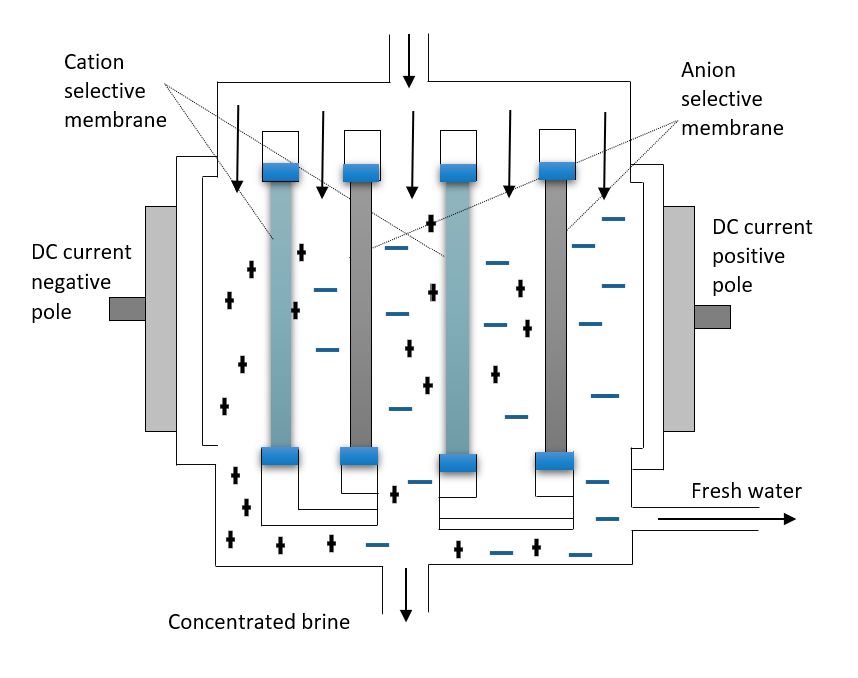

Electrodialysis (ED): Electrodialysis is an electrochemical process mainly applied in the desalination of brackish water, which works on the principle of ion migration in an electric field, as shown in Figure 5. During the process of ED, a direct current moves through the water to transport salt ions across ion exchange membranes, separating the salt from the feed water stream. ED is only capable of removing ionic components from the solution since the driving force for separation is an electric field. ED utilizes electromotive force applied to electrodes adjacent to both sides of a membrane to separate dissolved minerals in water. The individual membrane units where the mineral separation takes place are known as the cell pairs (Islam et al. 2018).

Desalination in the United States, Including Florida

Over the past 50 years, the desalination process has dramatically improved because of many years of research and innovation. During World War II, research was conducted on desalination to meet remote locations' freshwater needs, and countries like the United States continue to use these desalination technologies to meet the freshwater requirements of the national and global populace (Islam et al. 2018).

The total installed capacity of desalination plants in the United States has expanded from around 302 MGD in 2009 to about 479 MGD in 2022. California, Florida, and Texas, which are highly prone to water scarcity, are leading states in the usage of desalination technologies in the United States (Herber 2024). Currently, the largest desalination plant in the United States is the 50 MGD Claude "Bud" Lewis Carlsbad Desalination Plant in California (Herber 2024). Florida was one of the first states to accept desalinated groundwater as a source of drinking water (Hill 2012, fig. 2). Especially in coastal areas, desalination in this US state is essential for meeting water requirements and mitigating saltwater intrusion (i.e., the movement of saltwater into freshwater aquifers or other freshwater sources). Florida also leads the nation in desalination capacity, with more than 130 desalination plants (Aslan et al. 2023).

According to the South Florida Water Management District (n.d.), reverse osmosis is the most common method of treating brackish groundwater and seawater. The same source also reported that as of 2023, South Florida had about 38 brackish groundwater and 2 seawater desalination plants operating with a combined capacity of 292 MGD. Tampa Bay Water's Seawater Desalination Plant, located alongside the Big Bend Power Plant in Apollo Beach, receives up to 50 MGD of seawater from the power plant's cooling system. This enables the facility to produce up to 25 MGD of high-quality drinking water (Tampa Bay Water, n.d.).

According to the Florida regional water supply plans, Florida’s water management agencies identified over 600 MGD of potential sources of brackish and seawater desalination capacity to meet future demands (SFWMD, n.d.). Table 1 shows the top 10 countries that use the most desalination technology.

Table 1. Top 10 countries using desalination technologies (Islam et al. 2018).

Environmental Impact

Environmental considerations play a critical role in the design and implementation of desalination technologies. These systems produce two primary outputs: low-salinity freshwater and high-salinity concentrate (brine), both of which have specific environmental impacts. The most significant local environmental concerns arise from the discharge of brine and the chemicals used in the desalination process. Additionally, the high energy consumption of desalination systems contributes to global greenhouse gas emissions, which must be evaluated in the context of international climate agreements, such as the Kyoto Protocol, a landmark accord that influenced global climate policy discussions (UNFCCC 1997).

Local environmental impacts tend to be more immediate and pronounced compared to global effects, making them particularly important to address. Notably, the environmental implications differ between seawater and inland desalination plants, as well as between thermal and membrane systems. Each system presents unique environmental challenges. However, some common environmental factors can be identified across all desalination processes.

Impact on Source Water: Marine water intakes can cause impingement and entrainment. That means both large marine organisms like fish and tiny aquatic organisms, including plankton, fish eggs, and larvae, can be trapped or carried with the intake water, causing their injury and death. Using nearshore wells can minimize this threat, but it increases energy consumption. For inland desalination plants, brackish groundwater is a common intake source. Withdrawal of brackish groundwater can potentially harm the physical sustainability of the aquifer, prompt subsidence (the gradual sinking or settling of land), or cause saltwater intrusion, mainly when the aquifer is located near the sea or a water body with a higher salt concentration.

Impact from Concentration: The brine water produced by the desalination process, sometimes referred to as reject water, is a primary concern from an environmental perspective. When the source water is seawater, desalination requires the exclusion of suspended and dissolved solids. These solids are rejected with unprocessed water, increasing their density and solids concentration together with the chemicals added in the pretreatment stage. If the process is thermal, the temperature of the rejected water is higher than typical seawater temperatures, which can cause significant environmental impacts. In addition, increasing the salinity of the seawater near the intake can reduce the performance of the desalination system. Inland desalination systems usually discharge the rejected water into rivers, lakes, or wells. Therefore, it can have adverse environmental impacts on the receiving water body.

Issues with Desalinated Water Products: The desalination process does not remove all constituents and contaminants. This is more evident in RO systems, where a small fraction of ions (especially monovalent ions such as sodium and chloride) and dissolved organic molecules (e.g., some pesticides or herbicides) can pass through to the permeated water (National Research Council 2008). Boron and bromide are examples of two other potential contaminants that can go through single-pass RO desalination processes without being removed. Higher levels of boron may cause adverse health effects.

Impact from Gas Emissions: The energy used in the desalination process is primarily electricity and heat. Desalination plants produce large amounts of greenhouse gases due to high energy requirements. RO technology generally requires less energy than other desalination technologies, such as thermal systems.

Future Outlook

Desalination offers tremendous opportunities to address global water scarcity, particularly in arid and coastal regions. However, it faces challenges related to energy use, cost, and environmental impact. The future of desalination depends on advancements in energy efficiency, renewable integration, and sustainable brine management, as well as public acceptance and regulatory support.

The issue of its high energy demand, particularly for thermal desalination methods, contributes to substantial greenhouse gas emissions. Integrating renewable energy sources like solar and wind with desalination facilities could help reduce these environmental impacts (Assad et al. 2022; Islam et al. 2018). Another pressing concern is the disposal of brine, a byproduct that can negatively affect marine and land ecosystems. Innovative approaches, such as recovering valuable minerals from brine, present opportunities to turn this waste into a resource (National Research Council 2008).

Cost is another barrier, as the substantial capital and operational expenses of desalination technologies make them less accessible, especially in developing regions. Advances in materials, science, and modular system designs could help lower these costs and enable wider adoption (Beltrán and Koo-Oshima 2006). Moreover, as climate change exacerbates water scarcity, desalination systems must be equipped to handle varying water qualities and extreme environmental conditions, requiring robust infrastructure and advanced filtration technologies. Emerging solutions, including forward osmosis, hybrid systems, and the use of artificial intelligence for optimization, offer promising pathways to tackle these challenges and improve the efficiency and sustainability of desalination processes (Van der Bruggen and Vandecasteele 2002).

Concluding Remarks

Desalination projects require an environmental impact assessment (EIA) study to determine the impact the project can have on the environment. The EIA considers all environmental parameters and criteria. It evaluates the potential effects on air, land, and marine environments and proposes mitigation measures to reduce the environmental impact. Since the intake and discharge of water from and to the seas are similar between seawater desalination plants and power generation plants, the environmental aspects of this type of desalination system are known in more detail. On the other hand, inland desalination, especially RO systems, needs more studies and regulatory guidelines to protect the environment.

References

Ahmed, M. A., and S. Tewari. 2018. “Capacitive Deionization: Processes, Materials and State of the Technology.” Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 813: 178–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2018.02.024

Aslan, G., I. Penna, Z. Cakir, and J. Dehls. 2023. “Brackish-Water Desalination Plant Modulates Ground Deformation in the City of Cape Coral, Florida.” Science of Remote Sensing 7: 100077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srs.2023.100077

Assad, M. E. H., M. N. AlMallahi, M. A. Abdelsalam, M. AlShabi, and W. N. AlMallahi. 2022. “Desalination Technologies: Overview.” 2022 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences (ASET). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ASET53988.2022.9734991

Beltrán, J. M., and S. Koo-Oshima. 2006. “Water Desalination for Agricultural Applications.” In Proceedings of the FAO Expert Consultation on Water Desalination for Agricultural Applications. Land and Water Discussion Paper 5. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/a0494e

Benham, B., E. J. Ling, and K. Haering. 2019. “Virginia Household Water Quality Program: Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) in Household Water.” Publication 442-666. Virginia Cooperative Extension. https://www.wellwater.bse.vt.edu/files/BSE-260.pdf

Cath, T. Y., A. E. Childress, and M. Elimelech. 2006. “Forward Osmosis: Principles, Applications, and Recent Developments.” Journal of Membrane Science 281 (1–2): 70–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2006.05.048

Global Water Intelligence. 2023. IDRA—Desalination & Reuse Handbook 2023–2024.

Global Water Intelligence. 2024. IDRA—Desalination & Reuse Handbook 2024–2025. https://www.globalwaterintel.com/pages/idrahandbook

Haque, S. E. 2023. “The Effects of Climate Variability on Florida’s Major Water Resources.” Sustainability 15 (14): 11364. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411364

Herber, G. 2024. “What are the prominent desalination plants in USA and how do they contribute to the country’s water sustainability?” Medium, March 16. https://medium.com/@desalter/what-are-the-prominent-desalination-plants-in-usa-and-how-do-they-contribute-to-the-countrys-water-e1ee71c42f05

Hill, C. 2012. “Florida Brackish Water and Seawater Desalination: Challenges and Opportunities.” Florida Water Resources Journal, September. https://fwrj.com/techarticles/0912%20tech2.pdf

Islam, M. S., A. Sultana, A. H. Saadat, M. S. Islam, M. Shammi, and M. K. Uddin. 2018. “Desalination Technologies for Developing Countries: A Review.” Journal of Scientific Research 10 (1): 77–97. https://doi.org/10.3329/jsr.v10i1.33179

Kang, M., and R. B. Jackson. 2016. “Salinity of Deep Groundwater in California: Water Quantity, Quality, and Protection.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113 (28): 7768–7773. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1600400113

Kassis, Z. R., W. Guo, R. G. Maliva, W. S. Manahan, R. Rotz, and T. M. Missimer. 2023. “Pumping-Induced Feed Water Quality Variation and Its Impacts on the Sustainable Operation of a Brackish Water Reverse Osmosis Desalination Plant, City of Hialeah, Florida, USA.” Sustainability 15 (6): 4713. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064713

Martel, D. A. Fiscal Year 2022–2023 Annual Work Plan Performance. South Florida Water Management District.

National Research Council (NRC), Committee on Advancing Desalination Technology. 2008. Desalination: A National Perspective. The National Academies Press.

Paup, B. T., and G. B. Peyton V. 2022. The Future of Desalination in Texas. Texas Water Development Board. https://www.twdb.texas.gov/innovativewater/desal/doc/2022_TheFutureofDesalinationinTexas.pdf

South Florida Water Management District. n.d. “Desalination.” Accessed August 7, 2025. https://www.sfwmd.gov/our-work/alternative-water-supply/desalination

Tampa Bay Water. n.d. “Tampa Bay Seawater Desalination.” Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.tampabaywater.org/tampa-bay-seawater-desalination

UNFCCC. 1997. Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Kyoto Climate Change Conference, December 1997. https://unfccc.int/documents/2409

Van der Bruggen, B., and C. Vandecasteele. 2002. “Distillation vs. Membrane Filtration: Overview of Process Evolutions in Seawater Desalination.” Desalination 143 (3): 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0011-9164(02)00259-X