Introduction

Water quality is a broad term used to describe a range of physical, chemical, and/or biological characteristics of water. Many different factors contribute to water quality. The decision of whether the quality of a given water body is good or bad, whether it is acceptable or unacceptable, varies from place to place and depends on the intended use of that water body. For example, if you are concerned with drinking water quality, you would want to ensure that the water does not have anything that could harm human health, such as chemical or biological contaminants, but drinking water quality also must consider problematic tastes, odors, or colorations. In contrast, if you are concerned with the water quality of a natural lake, you might focus more on the dissolved oxygen and nutrient concentrations that can influence organisms in the lake, such as fish or invertebrates. The United States Geological Survey summarizes these points by defining water quality as “a measure of the suitability of water for a particular use based on selected physical, chemical, and biological characteristics” (Cordy 2001). In Florida, water quality criteria have been established for six different types of water bodies, and these criteria vary by the use of each water body type. The water body classifications are described in F.A.C. §62-302.400, and water quality criteria are located in F.A.C. §62-302.500 and §62-302.530. More detailed information on Florida water regulations is available in the Handbook of Florida Water Regulations.

This publication defines general terminology and approaches used to describe water quality. It is targeted toward individuals who have an interest in water quality issues but may not have training in specific details of these issues. The publication provides a baseline introduction to these terms for a non-expert but may also be useful as a review for individuals working in water quality regulation or monitoring. This publication focuses on chemical pollutants dissolved in water, but keep in mind that other types of pollutants also exist. Ultimately, this publication will allow the reader to have a deeper understanding of specific water quality issues and provide the terminology that is needed to engage in these topics.

Water Quality Terminology and Calculations

The various terms and calculations used to describe water quality related to pollutants can be confusing, but each term has a specific purpose. For this discussion, pollutants are defined as materials (e.g., pesticides, nutrients, or microplastics) that are present where they should not be or present at concentrations greater than normal for a given body of water.

Two common ways to characterize water quality parameters associated with chemical pollutants are concentration and load. The concentration of a pollutant is the ratio of pollutant mass or volume per volume of water. Concentrations are reported with units of mass per volume, such as parts per thousand (ppt) or milligrams per liter (mg/L), or volume per volume, which is often reported as a percentage. For example, the concentration of salt in ocean water is approximately 35 grams per liter, which is equal to 35 ppt. This means that for every liter of ocean water, there are 35 grams of salt dissolved in it. In contrast, a pollutant load is the total amount (or mass typically) of a pollutant in or carried by a particular water body within a particular timeframe. Loads are reported using units that reflect the mass of a pollutant carried by a particular water body for a specific timeframe, such as kilograms per day (kg/d) or pounds per year (lb/y). To calculate pollutant load, you need to know the pollutant concentration and the applicable flow rate. The flow rate is the volume of water moving past a fixed location over a period of time. Flow rate is reported in units of volume per time, such as cubic feet per second (ft3/s, sometimes reported as cfs) or liters per second (L/s). The flow rate can be calculated using the average water velocity and cross-sectional area (width × depth) of the water body. Flowing water bodies (e.g., streams, rivers) carry a pollutant load. The pollutant load entering a non-flowing water body, such as a pond or a lake, can be represented by the mass of a pollutant in water flowing into that water body in a given time period. The pollutant load of a given water body is calculated as the concentration of a pollutant in the water (mg/L or lb/ft3) multiplied by the flow rate (L/s or ft3/s):

Load (lb/s) = Pollutant concentration (lb/ft3) × Flow rate (ft3/s)

The units cancel as the following: lb/ft3 × ft3/s = lb/s

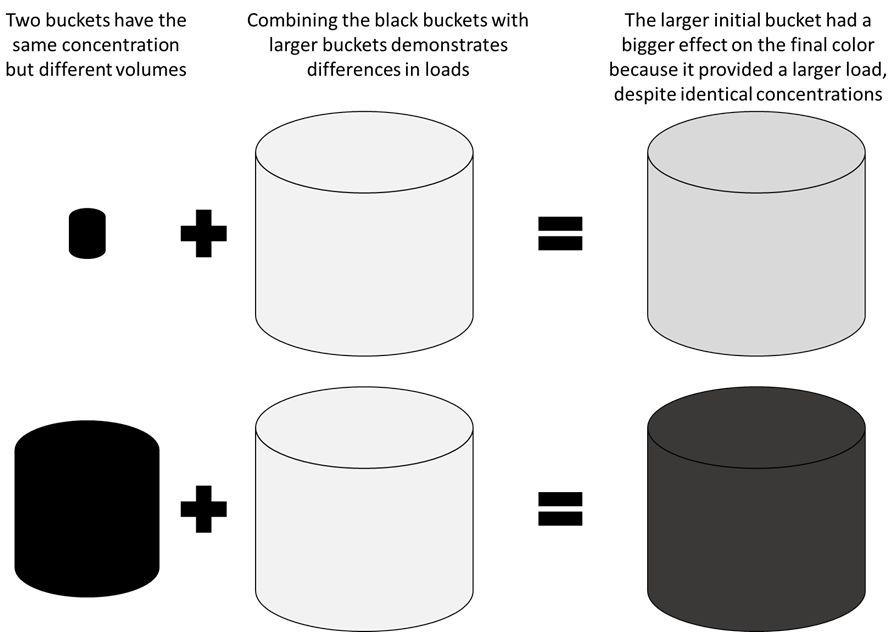

A useful way to visualize the relationship between pollutant concentration and load is to imagine you have a 1-gallon coffee carafe and a coffee mug filled with coffee directly from the carafe. The carafe and the mug have the exact same coffee in them, so the concentration is identical, and they would taste the same if you took a drink from either. Now imagine adding sugar to your coffee. If you add 1 tablespoon to the mug and 1 tablespoon to the carafe, you are adding the same load of sugar, but they will no longer taste the same. To have the two containers continue tasting the same, you would need to add more sugar (a larger load) to the carafe than to the mug. Similarly, a stream draining into a lake will contribute a much smaller load of a pollutant than if a large river with the same pollutant concentration was draining into the lake. Figure 1 provides a cartoon visualization similar to this scenario, and Figure 2 provides a satellite image visualizing sediment loads to the coast.

Credit: "Sediment Spews from Connecticut River" by NASA Goddard Photo and Video, licensed under CC BY 2.0

Which water quality parameter is more important?

Unsurprisingly, it depends. Knowing the concentration of a pollutant is important if you are concerned with questions related to how the pollutant is impacting organisms in the water (often referred to as toxicity or nuisance conditions). For example, the concentration of dissolved oxygen in the water is crucial for aquatic life. If dissolved oxygen concentrations (mg/L) are too low, the water is described as hypoxic (low in oxygen) or anoxic (containing no oxygen), which can lead to fish kills. Another example is related to human health. The US Environmental Protection Agency has set a standard limit for nitrate in drinking water at 10 mg/L. This limit is set to prevent the development of methemoglobinemia in humans (also known as blue baby syndrome). In this case, nitrate enters the bloodstream and bio-transforms into nitrite. Then, the nitrite alters the oxygen carrying capacity of hemoglobin molecules, reducing the distribution of oxygen throughout the body. Most water quality regulations are based on pollutant concentration thresholds because pollutant concentration is important for human and/or environmental health.

In contrast to concentration, pollutant loads are important to consider when you are interested in the accumulation of a pollutant. For example, if you are trying to figure out how long it will take for a reservoir to fill with sediments, you would need to know the sediment load over time. Alternatively, if you are interested in how effective agricultural best management practices (BMPs) are at reducing phosphorus export from the edge-of-fields or to coastal estuaries through canals or streams, you would want to know the phosphorus load. In the BMP example, knowing the load is important because BMPs can reduce pollutant export by reducing the concentration of a pollutant, the flow rate, or both. If there was no change in concentration after implementing BMPs, you might think that the BMPs were ineffective. However, it could be that the BMPs reduced the total flow rate, thus reducing the load despite no change in concentration.

Concentrations and loads are closely linked when considering water quality regulations. Water quality regulations/standards are designed to protect water according to their designated uses (drinking, recreation, wildlife, etc.) and are commonly based on pollutant concentration limits. For example, the Florida legislature has set water quality standards for different types of lakes throughout the state based on water column chlorophyll a (a measure of the amount of algae in the water), total phosphorus, and total nitrogen. For blackwater lakes, the chlorophyll a standard states that the annual average concentration of chlorophyll a should not exceed 20 µg/L more than once in any consecutive three-year period (F.A.C. §62-302.531). If a water body does not meet these water quality standards (e.g., chlorophyll a in a blackwater lake exceeds 20 µg/L), the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) identifies the water body as “impaired” for not meeting water quality standards.

Once the FDEP identifies a water body as impaired, the department establishes and adopts a total maximum daily load (TMDL) for the pollutant(s) of concern causing the impairment. By definition, TMDLs are the established maximum pollutant load that can be contributed to a given water body while still allowing that water body to achieve water quality standards based on pollutant concentration. Following the adoption of a TMDL, the FDEP works closely with local partners to develop a plan for how the TMDL will be met. There are a few different ways to accomplish this planning process, including Reasonable Assurance Plans (RAPs) and Basin Management Action Plans (BMAPs). Additional information on RAPs and BMAPs is available through the FDEP website. For more details on US and Florida water quality regulations, see the following EDIS publications from the 2021 Handbook of Florida Water Regulations: FE1043, “Florida Water Resources Policy,” and FE608, “Florida Watershed Restoration Act.”

Summary

There are many different factors that contribute to water quality, and different pollutants can be more or less problematic depending on the water body and its intended usage. Regardless of the pollutant, water body, or usage being considered, it is important to understand the difference between pollutant concentration and pollutant load. This publication has defined pollutant concentration and pollutant load, provided examples of each, and described why both concentrations and loads are important factors when considering water quality regulations. The principles described can apply to many different water quality constituents, providing the reader with a better understanding of how and when use of concentrations and loads is most appropriate.

Reference

Cordy, G. E. 2001. “A Primer on Water Quality.” United States Geological Survey Fact Sheet 027-01. https://doi.org/10.3133/fs02701