Introduction

Organic soils (Histosol), though accounting for only 3% of terrestrial soils (FAO 2020), are among the most fertile soils globally (Kramer and Shabman 1993; Inisheva 2006), supporting extensive agricultural production in North America, Northern and Eastern Europe, Canada, Siberia, and Southeast Asia (Kuhry et al. 1993; Glaser et al. 2004; Parent and Ilnicki 2002; Caron et al. 2015). These soils form from plant remains that accumulate through time under seasonally flooded or flooded wetlands such as bogs, fens, swamps, and marshes (NWWG 1988). However, the anaerobic conditions of these environments lead to oxygen depletion in the soil. This lack of oxygen poses agronomic challenges, such as by hindering seed germination, plant growth, and yield (Alpi and Beevers 1983; Perata and Alpi 1993; Magneschi and Perata 2009). To overcome these agronomic challenges, drainage is widely implemented to enhance the productivity of organic soils (Kramer and Shabman 1993). Although drainage is essential for improving their productivity, it exposes soil organic matter (SOM) to oxygen, stimulating microbial activity associated with SOM decomposition, which leads to accelerated carbon loss—a phenomenon known as organic soil subsidence (Armentano 1980; Schothorst 1982; Byrne et al. 2004; Pereira et al. 2005; Drösler et al. 2008; Bhadha, Wright, et al. 2020). Many studies have reported soil carbon loss as a result of draining organic soils for agricultural use. For example, the annual carbon losses, ranging between 1 and 11 t C ha⁻¹ (tons of carbon per hectare), have been reported in drained temperate organic soils formed under fen wetlands (Kasimir-Klemedtsson et al. 1997; Byrne et al. 2004; Höper et al. 2008). Organic soil loss is happening in different parts of the world, including the Everglades Agricultural Area (EAA) situated in south Florida, United States.

By recognizing the importance of soil conservation, the USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) has initiated a comprehensive conservation plan for on-farm management of all natural resources (USDA-NRCS 2020). In this plan, USDA-NRCS recommends 32 conservation and environmental farming practices to best conserve the land’s natural resources, while offering growers the opportunity for improving farm sustainability and productivity. From these 32 practices, four of them are well-suited for managing organic soil loss within the EAA: cover crop (#5), crop rotation (#6), soil organic amendments (#16), and conservation tillage (#17). This factsheet provides specific insights for commercial growers, landowners, farm managers, and Extension faculty on promising conservation practices for organic soils of the EAA, thereby promoting their adoption for sustaining agricultural production.

Constraints Associated with Organic Soil Management in South Florida

Reductions in soil organic matter (SOM), increases in soil bulk density, changes in soil pH, and declines in soil porosity are major concerns for organic soils drained for agricultural use. When these soils are drained for agriculture or other uses, oxygen starts to permeate through the topsoil, promoting soil microorganisms to start decomposing organic materials at a higher rate. As a result, peat soil decomposition exceeds the rate of accumulation, thereby lowering surface elevation, a process commonly referred to as soil subsidence (Bhadha, Wright, et al. 2020). After drainage, soil subsidence is further accelerated by other processes, including compaction by farm equipment, shrinkage, water and wind erosion, and prescribed fires.

Organic soil subsidence after drainage is globally well known; for example, Figure 1 illustrates how organic soil subsidence has been taking place in the EAA. In addition, Aich and Dreschel (2011) estimated 7.1 x 109 m3 of peat, equivalent to 1.4 times the volume of Lake Okeechobee, have been lost over the past 130 years within the Everglades (EAA and Everglades Protection Area, which include five Water Conservation Areas and the Everglades National Park).

Credit: Noel Manirakiza and Jehangir Bhadha, UF/IFAS

Ways to Slow Down Soil Loss within the Everglades Agricultural Area

Draining organic soils for agricultural purposes is common worldwide because of the significant economic benefits these fertile soils provide (Kramer and Shabman 1993). However, to mitigate the loss of organic soils, the implementation of conservation practices is strongly recommended. This section discusses four recommended conservation agricultural practices in detail, including cover crops, conservation tillage, crop rotation, and organic amendments that can potentially conserve organic soil loss within EAA (Figure 2).

Credit: Noel Manirakiza and Jehangir Bhadha, UF/IFAS

Benefit Symbols

The figures use six symbols to highlight the benefits offered by each of the following four conservation practices: (1) cover crops; (2) conservation tillage; (3) crop rotation; and (4) organic amendments. Table 1 lists the explanations of each symbol.

Table 1. Symbols and their associated soil conservation benefits.

Credit: Noel Manirakiza and Jehangir Bhadha, UF/IFAS

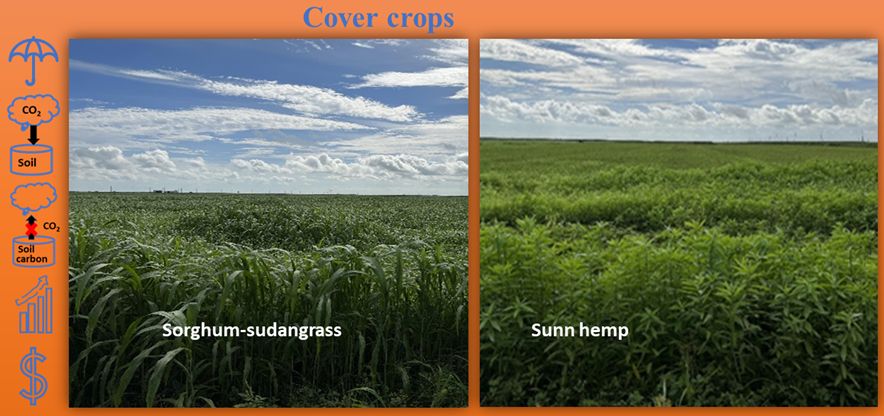

What are cover crops?

Cover crops are non-cash crops grown either in monoculture or mixture after harvesting cash crops to protect or improve soils. Cover crops are usually grown to make use of the time between cash crop seasons. Once the cover crop season ends, farmers terminate the cover crop and incorporate them into the soil. This adds organic matter, recycles nutrients, and improves soil conditions for the next cash crop. Typically, the fallow period within the EAA is considered the summer months, which are too hot and wet to sustain most cash crops except rice and sugarcane. Hot weather cover crops, commonly known as summer cover crops, such as sorghum-sudangrass (Sorghum bicolor), Sunn hemp (Crotalaria juncea), buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum), Japanese millet (Echinochloa esculenta), foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.), pearl millet (Cenchrus americanus), cowpeas (Vigna unguiculata), and bush green beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) (Creamer and Baldwin 2019), can work well in the EAA because they can germinate well in summer. Although, buckwheat is typically grown in spring and fall, not summer; has a short growing season; and has low biomass, requiring careful management to prevent it from going to seed and becoming a weed. Beyond the EAA, growers who have farms located in cool weather environments can also reap the benefits of cover crop use. In winter, cool weather cover crops, commonly known as winter cover crops, such as crimson clover (Trifolium incarnatum L.), winter or cereal rye (Secale cereale), oat (Avena sative), triticale (Triticosecale Wittmack), black oat (Avena strigosa Schreb), mustards (Brassica juncea), hairy vetch (Vicia villosa Roth), and Austrian peas (Pisum sativum L. ssp.) can work well (Shaughnessy et al. 2017; Reicosky et al. 2021).

How They Help

- Cover crops provide soil cover, which prevents soil loss by water and wind erosion (Creamer and Baldwin 2019).

- Cover crops enhance carbon input by using sunlight to harvest carbon from the atmosphere and transfer it to the soil in the form of SOM after cover crop incorporation into soil (Creamer and Baldwin 2019). The accumulated SOM, thereby, improves soil health. By accumulating moisture and cooling the soil, cover crops reduce microbial activity associated with SOM mineralization, thus preventing the oxidation (loss) of existing SOM.

- Cover crops enrich topsoil with nutrients by using their deep roots to absorb nutrients from deeper soil layers and bring them to the topsoil where shallow-rooted cash crops can access them (Creamer and Baldwin 2019). Leguminous cover crops, in particular, biologically fix atmospheric nitrogen (Creamer and Baldwin 2019). This enrichment of soil fertility boosts agricultural profits by reducing the need for chemical fertilizers and lowering input costs.

- Cover crops enhance nutrient cycling within the plant-soil system by absorbing residual nutrients that would otherwise be lost via leaching. This process improves water quality by preventing excess nutrient runoff. The nutrients absorbed into cover crop tissues are released to subsequent crops as cover crop biomass decomposes.

- Cover crops manage pests such as weeds and diseases in subsequent cash crops (Creamer and Baldwin 2019). Weeds compete with cash crops for resources such as nutrients, light, and water, limiting plant growth and yield. Some cover crops help mitigate this issue by releasing chemicals that inhibit weed seed germination.

- Cover crop roots exude substances that feed beneficial soil organisms (e.g., mycorrhizae fungi), playing important roles in improving soil functions.

Planning Ahead

- Keep in mind that cover crops are grown for different benefits.

- To maximize all cover crop benefits, growing a mixture of cover species is of paramount importance. To choose cover species for your farm, first clarify your goal for growing cover crops. Do you want to prevent soil erosion, accumulate SOM, reduce soil compaction, and/or add nutrients like nitrogen?

Technical Notes

- As biomass production increases, so do the cover crop benefits. Thus, use only high-quality seeds at the company’s recommended seeding rate to produce more biomass. For example, in south Florida, growers typically apply 25–30 lb/acre.

- If your farm is in a hot weather environment, you should consider hot weather cover crops (i.e., summer cover crops). Under cool weather conditions, you should consider cold weather cover crops (i.e., winter cover crops).

- Planting mixtures of cover crop species can help optimize the soil benefits associated with cover cropping practice.

Maintenance

- The longer the growing season lasts, the more carbon is sequestered, and the more nutrients are absorbed into cover crop biomass. Once the cover crops are terminated and incorporated into the soils, biomass starts to decompose and gradually release nutrients for subsequent cash crops, improving SOM. SOM plays a crucial role in enhancing the ability of soils to retain more water and nutrients. Cover crops should be terminated at (or just before) flowering to maximize all soil benefits associated with them. Delaying termination increases the carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratio, making the plant material more resistant to decomposition and potentially leading to nutrient immobilization.

Credit: Noel Manirakiza and Jehangir Bhadha, UF/IFAS

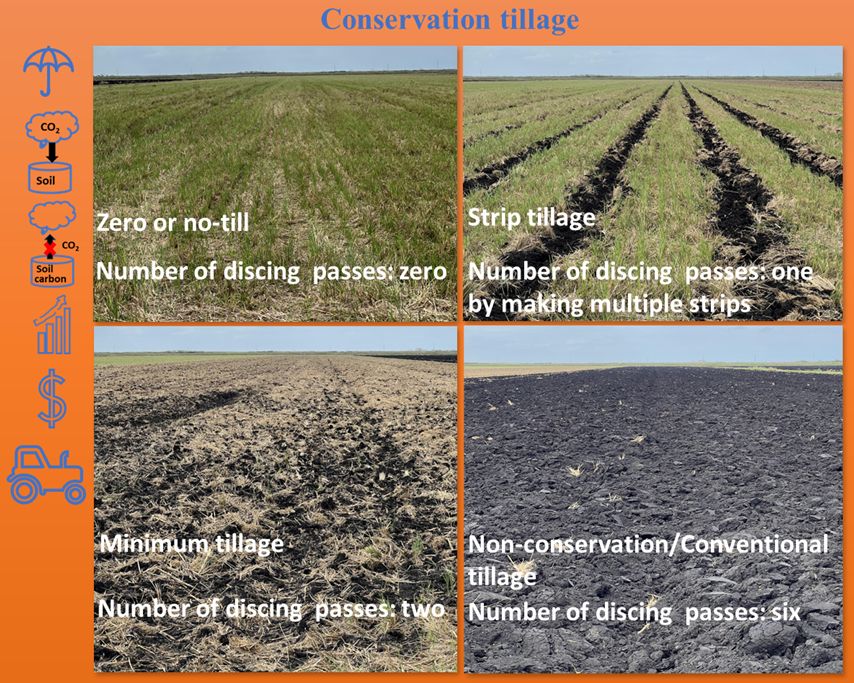

What is conservation tillage?

Conservation and conventional tillage practices are both practices used for land preparation prior to planting crops. The difference between the two lies in their level of soil disturbance. Conservation tillage practices (no-till, strip till, and minimum tillage) are characterized by minimal soil disturbance, while conventional tillage, also known as intensive or non-conservation tillage, is characterized by excessive soil disturbance.

How It Helps

- Conservation tillage, particularly zero tillage, maintains surface soil cover by retaining crop residues on the soil surface (Busari et al. 2015).

- This practice prevents soil loss from water and wind erosion by forming and stabilizing soil macroaggregates (Gambolati et al. 2005; Bhatt and Khera 2006). Stabilized soil macroaggregates prevent soil microorganisms from accessing SOM locked up within aggregates and, in turn, prevent the loss of existing SOM. This practice can be the ideal solution for mitigating soil subsidence in the EAA.

- Cutting the cost of agricultural inputs such as fuel, renting tractors, and so forth, can save money and increase agricultural profits.

- Reducing farm traffic prevents soil subsidence.

- Conservation tillage cools the soil by increasing moisture retention, which can reduce microbial activities essential for SOM mineralization. This process also prevents soil shrinkage and reduces the risk of accidental muck fires—factors that contribute to soil subsidence.

- SOM buildup improves soil health and fertility (Ecowworld 2024).

Planning Ahead

- Do you have the right farm equipment?

- Are the weather conditions conducive for farm operations?

Technical Notes

- Soil compaction from heavy farm equipment causes organic soils to subside. So, it is advisable to keep farm traffic at minimal levels.

Credit: Noel Manirakiza and Jehangir Bhadha, UF/IFAS

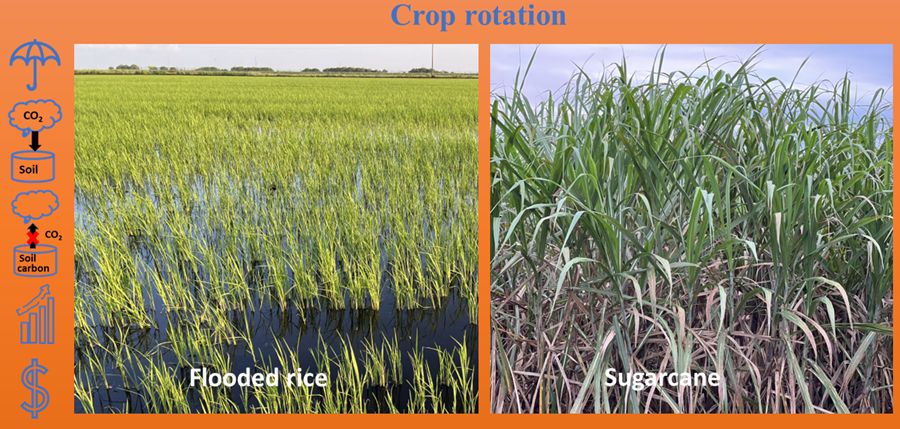

What is crop rotation?

In organic soils facing soil loss, a conservation crop rotation means cultivating various water-tolerant crops on the same farm in a recurring sequence. Flooded rice (Oryza sativa) and sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) as water-tolerant crops are grown in rotation to reduce organic soil loss within the EAA. There, approximately 445,000 acres of organic soils are used for sugarcane production, and over 50,000 acres of fallow sugarcane land are available for rice production (Bhadha et al. 2016). The rice fields are flooded by pumping water from the canals at flood depths ranging between 5 and 20 cm in EAA (Bhadha et al. 2018; Tootoonchi et al. 2018). Previous studies have shown that keeping organic soil saturated slows the decomposition process (Hendriks et al. 2007; Waddington et al. 2010; Worrall et al. 2010). Therefore, increasing rice acreage could be a viable solution to slowing soil loss in the EAA.

How It Helps

- Growing water-tolerant crops in rotation keeps soils saturated. This condition deprives soil microorganisms of oxygen, reducing the loss of existing SOM by suppressing microbial activity related to carbon mineralization. Such saturated soil conditions also prevent shrinkage and prescribed muck fires. In the EAA, flooded rice cultivation helps in improving soil health and water quality (Fan et al. 2024; Bai et al. 2025).

- Both sugarcane and flooded rice cultivation accumulate new SOM by photosynthetically sequestering atmospheric CO2 and storing it in the soil in the form of SOM. These benefits of SOM buildup lead to soil health improvement (Trace X Technologies 2025).

- Crop rotation controls weeds and pests (Davis 2024).

- Cultivating flooded rice and sugarcane offers local community employment.

Planning Ahead

- Incorporate only water-tolerant crops into the rotation. Flooded fallow (flooded, uncropped land) can serve as an alternative to flooded rice cultivation, instead of relying on traditional fallow practices (uncropped land).

- Design a crop rotation that produces a large amount of crop residues. Crop residues are left on the soil at harvest to increase carbon inputs to the soil.

Technical Notes

- Plant flooded rice at the right time and rate. In south Florida, growers plant rice between March and May at a seeding rate of 70 lb/acre.

- Maintaining soil saturation is key to soil conservation. It is advisable to regularly monitor soil water tables and, in cases where water tables are low, try to raise their levels via pumping water in the field.

Maintenance

- Monitor and control pests such as rice stink bug, plant hoppers, rice delphacid, and stem borer to avoid crop damage and attendant yield loss.

Credit: Noel Manirakiza and Jehangir Bhadha, UF/IFAS

What is an organic amendment?

Organic amendments are organic materials applied to the topsoil to improve soil properties and plant growth. These amendments include, but are not limited to, compost, bagasse, mill mud, manure, straw, wood chips, and biosolids. Bagasse is a fibrous material left after extracting sugar juice from sugarcane stocks, while mill mud is a solid material left after filtering the extracted cane juice (Alvarez-Campos et al. 2018). In south Florida, the sugarcane industry produces over 2.5 million metric tons of bagasse (Bhadha, Xu, et al. 2020), and its application as a soil amendment can potentially conserve soil loss in the EAA.

How It Helps

- Improving soil aggregation and stability prevents erosion.

- Reducing soil compaction improves root growth and development (Negiş et al. 2020).

- Organic amendments add new SOM to the soil system (Şeker and Manirakiza 2020).

- Organic amendments can act as an alternative energy source for microbial respiration to prevent existing SOM oxidation.

- SOM buildup improves soil properties and overall soil fertility (Manirakiza and Şeker 2018, 2020; Manirakiza et al. 2021).

- As organic amendments are rich in plant nutrients, they can potentially save growers money by reducing the cost of purchasing chemical fertilizers.

Planning Ahead

- Do you have enough organic amendments available for your farm size?

- Do you have farm equipment for transportation and application?

Technical Notes

- Apply organic amendments prior to the wet season, as moisture is essential for their mineralization and nutrient release. Both processes are important for plant uptake. This practice also contributes to the accumulation of SOM in the soil over time, improving soil structure and fertility.

- Mixing two amendments, such as bagasse and mill mud, can improve soil better than applying single amendments. The combined OM from both amendments helps build up SOM over time, enhancing soil fertility, moisture retention, and structure compared to using a single amendment.

Maintenance

- After applying amendments to the field, it is highly advisable to keep the field moist to protect against the wind blowing away the applied amendments once they dry.

Summary

Organic soils (Histosols) have high inherent fertility, making them suitable for crop production. To facilitate farming, drainage of the soil must occur first to remove excessive moisture, but this leads to organic soil loss. Managing organic soil loss is necessary to increase the longevity of these soils. This factsheet describes four potential conservation and environmental farming practices recommended by USDA-NRCS that can be well suited for conserving organic soil loss within the EAA. These practices include the use of cover crops, crop rotation (flooded rice with sugarcane), conservation tillage, and the application of organic amendments. These practices have been adopted by growers in the EAA and have shown a positive impact on conserving organic soil loss. Expanding both the adoption and acreage of these practices is strongly recommended to further reduce soil loss within the EAA.

References

Aich, S., and T. W. Dreschel. 2011. “Evaluating Everglades Peat Carbon Loss Using Geospatial Techniques.” Florida Scientist 2011 74: 63–71.

Alpi, A., and H. Beevers. 1983. “Effects of O2 Concentration on Rice Seedlings.” Plant Physiology 71 (1): 30–34. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.71.1.30

Alvarez-Campos, O., T. A. Lang, J. H. Bhadha, J. M. McCray, B. Glaz, and S. H. Daroub. 2018. “Biochar and mill ash improve yields of sugarcane on a sand soil in Florida.” Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 253: 122–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.11.006

Armentano, T. V. 1980. “Drainage of Organic Soils as a Factor in the World Carbon Cycle.” BioScience 30 (12): 825–830. https://doi.org/10.2307/1308375

Bai, X., S. J. Smidt, Y. G. Her, et al. 2025. “Sensitivity of Redox Conditions to Irrigation Practice and Organic Matter Decomposition in a Rotational Flooded Rice (Oryza sativa) Cropping System.” Journal of Environmental Quality. https://doi.org/10.1002/jeq2.70087

Bhadha, J. H., R. Khatiwada, S. Galindo, N. Xu, and J. Capasso. 2018. “Evidence of Soil Health Benefits of Flooded Rice Compared to Fallow Practice.” Sustainable Agriculture Research 7 (4): 31–41. https://doi.org/10.5539/sar.v7n4p31

Bhadha, J. H., T. Luigi, and M. VanWeelden. 2016. “Trends in Rice Production and Varieties in the Everglades Agricultural Area.” EDIS 2016 (6). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-ss653-2016

Bhadha, J. H., A. L. Wright, and G. H. Snyder. 2020. “Everglades Agricultural Area Soil Subsidence and Sustainability: SL 311/SS523, rev. 3/2020.” EDIS 2020 (2). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-ss523-2020

Bhadha, J. H., N. Xu, R. Khatiwada, S. Swanson, and C. LaBorde. 2020. “Bagasse: A Potential Organic Soil Amendment Used in Sugarcane Production: SL477/SS690, 8/2020.” EDIS 2020 (5). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-ss690-2020

Bhatt, R., and K. L. Khera. 2006. “Effect of Tillage and Mode of Straw Mulch Application on Soil Erosion in the Submontaneous Tract of Punjab, India.” Soil and Tillage Research 88 (1–2): 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2005.05.004

Busari, M. A., S. S. Kukal, A. Kaur, R. Bhatt, and A. A. Dulazi. 2015. “Conservation Tillage Impacts on Soil, Crop and the Environment.” International Soil and Water Conservation Research 3 (2): 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iswcr.2015.05.002

Byrne, K. A., B. Chojnicki, T. R. Christensen, et al. 2004. “EU Peatlands: Current Carbon Stocks and Trace Gas Fluxes, Report 4/2004.” In Concerted Action: Synthesis of the European Greenhouse Gas Budget. Geosphere-Biosphere Centre.

Caron, J., J. S. Price, and L. Rochefort. 2015. “Physical Properties of Organic Soil: Adapting Mineral Soil Concepts to Horticultural Growing Media and Histosol Characterization.” Vadose Zone Journal 14 (6): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2014.10.0146

Davis, E. 2024. “Understanding the Relationship Between Crop Rotation and Weed Management.” Husfarm, March 3. Archived June 21, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240621020833/https://husfarm.com/article/understanding-the-relationship-between-crop-rotation-and-weed-management

Drösler, M., A. Freibauer, T. R. Christensen, and T. Friborg. 2008. “Observations and Status of Peatland Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Europe.” In The Continental-Scale Greenhouse Gas Balance of Europe, edited by A. J. Dolman, R. Valentini, and A. Freibauer. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-76570-9_12

Ecowworld. 2024. “How Conservation Tillage Practices Improve Soil Health and Boost Yields.” Ecowworld, July 25. https://ecowworld.com/conservation-tillage-benefits-soil/

Fan, Y., N. R. Amgain, A. Rabbany, et al. 2024. “Assessing Flood-Depth Effects on Water Quality, Nutrient Uptake, Carbon Sequestration, and Rice Yield Cultivated on Histosols.” Climate Smart Agriculture 1 (1): 100005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csag.2024.100005

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 2020. Peatland Mapping and Monitoring—Recommendations and Technical Overview. http://www.fao.org/3/CA8200EN/CA8200EN.pdf

Gambolati, G., M. Putti, P. Teatini, et al. 2005. “Peat land oxidation enhances subsidence in the Venice watershed.” Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union 86 (23): 217–220. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005EO230001

Glaser, P. H., B. C. S. Hansen, D. I. Siegel, A. S. Reeve, and P. J. Morin. 2004. “Rates, Pathways and Drivers for Peatland Development in the Hudson Bay Lowlands, Northern Ontario, Canada.” Journal of Ecology 92 (6): 1036–1053. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-0477.2004.00931.x

Hendriks, D. M. D., J. van Huissteden, A. J. Dolman, and M. K. van der Molen. 2007. “The Full Greenhouse Gas Balance of an Abandoned Peat Meadow.” Biogeosciences 4 (3): 411–424. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-4-411-2007

Höper, H., J. Augustin, J. P. Cagampan, et al. 2008. “Restoration of Peatlands and Greenhouse Gas Balances.” In Peatlands and Climate Change, edited by M. Strack. International Peat Society. https://edepot.wur.nl/39508

Inisheva, L. I. 2006. “Peat Soils: Genesis and Classification.” Eurasian Soil Science 39: 699–704. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1064229306070027

Kasimir-Klemedtsson, Å., L. Klemedtsson, K. Berglund, P. Martikainen, J. Silvola, and O. Oenema. 1997. “Greenhouse Gas Emission from Farmed Organic Soils: A Review.” Soil Use and Management 13 (s4): 245–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-2743.1997.tb00595.x

Kramer, R. A., and L. Shabman. 1993. “The Effects of Agricultural and Tax Policy Reform on the Economic Return to Wetland Drainage in the Mississippi Delta Region.” Land Economics 69 (3): 249–262. https://doi.org/10.2307/3146591

Kuhry, P., B. J. Nicholson, L. D. Gignac, D. H. Vitt, and S. E. Bayley. 1993. “Development of Sphagnum-Dominated Peatlands in Boreal Continental Canada.” Canadian Journal of Botany 71: 10–22. https://doi.org/10.1139/b93-002

Magneschi, L., and P. Perata. 2009. “Rice Germination and Seedling Growth in the Absence of Oxygen.” Annals of Botany 103 (2): 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcn121

Manirakiza, N., and C. Şeker. 2018. “Effects of Natural and Artificial Aggregating Agents on Soil Structural Formation and Properties—a Review Paper.” Fresenius Environmental Bulletin 27 (12A): 8637–8657.

Manirakiza, N., and C. Şeker. 2020. “Effects of Compost and Biochar Amendments on Soil Fertility and Crop Growth in a Calcareous Soil.” Journal of Plant Nutrition 43 (20): 3002–3019. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904167.2020.1806307

Manirakiza, N., C. Şeker, and H. Negiş. 2021. “Effects of Woody Compost and Biochar Amendments on Biochemical Properties of the Wind Erosion Afflicted a Calcareous and Alkaline Sandy Clay Loam Soil.” Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 52 (5): 487–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/00103624.2020.1862148

Creamer, N., and K. Baldwin. 2019. “Summer Cover Crops.” Horticultural Information Leaflets. NC State Extension Publications. Revised July 18, 2019. Archived December 24, 2019, at https://web.archive.org/web/20191224231128/https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/summer-cover-crops

National Wetland Working Group (NWWG). 1988. Wetlands of Canada. Ecological Land Classification Series No. 2.

Negiş, H., C. Şeker, I. Gümüş, N. Manirakiza, and O. Mücevher. 2020. “Effects of Biochar and Compost Applications on Penetration Resistance and Physical Quality of a Sandy Clay Loam Soil.” Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 51 (1): 38–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/00103624.2019.1695819

Parent, L. E., and P. Ilnicki, eds. 2002. Organic Soils and Peat Materials for Sustainable Agriculture. CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420040098

Perata, P., and A. Alpi. 1993. “Plant Responses to Anaerobiosis.” Plant Science 93 (1–2): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-9452(93)90029-Y

Pereira, M. G., L. D. Anjos, and G. S. Valladares. 2005. “Organossolos: Ocorrência, gênese, classificação, alterações pelo uso agrícola e manejo.” In Tópicos em ciência do solo, editado por P. V. Torrado, L. R. F. Alleoni, M. Cooper, A. P. Silva, and E. J. Cardoso. Sociedade Brasileira de Ciência do Solo 4: 233–276.

Reicosky, D. C., A. Calegari, D. R. dos Santos, and T. Tiecher. 2021. “Cover Crop Mixes for Diversity, Carbon and Conservation Agriculture.” In Cover Crops and Sustainable Agriculture, edited by R. Islam and B. Sherman. 1st ed. CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003187301-11

Schothorst, C. J. 1982. Drainage and Behaviour of Peat Soils. Report No. 3. Institute for Land and Water Management Research. ICW.

Şeker, C., and N. Manirakiza. 2020. “Effectiveness of Compost and Biochar in Improving Water Retention Characteristics and Aggregation of a Sandy Clay Loam Soil Under Wind Erosion.” Carpathian Journal of Earth and Environmental Sciences 15 (1): 5–18. https://doi.org/10.26471/cjees/2020/015/103

Shaughnessy, D., R. F. Polomski, L. Burgess, and T. Corny. 2017. “Cover Crops.” Home & Garden Information Center. Factsheet No.1252. Clemson Cooperative Extension. https://hgic.clemson.edu/factsheet/cover-crops/

Tootoonchi, M., J. H. Bhadha, T. A. Lang, J. M. McCray, M. W. Clark, and S. H. Daroub. 2018. “Reducing Drainage Water Phosphorus Concentration with Rice Cultivation Under Different Water Management Regimes.” Agricultural Water Management 205: 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2018.04.036

Trace X Technologies. 2023. “5 Benefits of Crop Rotation for Sustainable Agriculture.” Trace X, June 2. https://tracextech.com/5-benefits-of-crop-rotation-for-sustainable-agriculture/

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service (USDA-NRCS). 2020. Conservation Choices: Your Guide to 32 Conservation and Environmental Farming Practices. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2022-09/ConservationChoices_2020.pdf

Waddington, J. M., W. T. Gruenwald, C. Rebmann, et al. 2010. “Toward Restoring the Net Carbon Sink Function of Degraded Peatlands: Short-Term Response in CO2 Exchange to Ecosystem-Scale Restoration.” Journal of Geophysical Research Biogeoscience 115 (G1): G04044. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JG001090

Worrall, F., M. J. Bell, and A. Bhogal. 2010. “Assessing the Probability of Carbon and Greenhouse Gas Benefit from the Management of Peat Soils.” Science of the Total Environment 408 (13): 2657–2666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.01.033