Introduction

This publication will provide examples of how AI can potentially improve the forecasting of water resource variables at both the field and regional levels. It is primarily intended for Extension educators, environmental and water resources consultants, farmers, researchers, and students who want to know more about AI systems and their applications in agriculture and the environment. By exploiting the opportunities that AI brings, stakeholders will gain insights into the advantages of smart technologies for environmental monitoring (Campbell 2021).

Accurate forecasting of surface water discharge and groundwater levels is essential for effective water resource management, especially in regions like Florida, where these resources are vital to the local ecosystem and economy. Florida's unique hydrological characteristics, including an extensive surface water network and the productive Floridan Aquifer, present a complex yet crucial area for hydrological studies.

The advent of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), an emerging transformative technology, has permeated every aspect of our lives, from computer vision to healthcare and now the environment (Russell and Norvig 2016; Botache and Guzman 2024). As highlighted by McAfee and Brynjolfsson (2017) and Choi et al. (2023), these technologies are redefining how to approach problems, providing innovative, scalable, and efficient solutions to complex challenges in diverse fields.

Nowadays, hydrological systems are becoming increasingly complex, a consequence of the growing interaction between nature and humans from the local scale of river sections, lakes, reservoirs, and so forth, to the global scale (Hannah et al. 2011). In addition, the climate drives the hydroclimatic characteristics of an area, affecting the availability of natural resources, soil health, the functioning and services of ecosystems, and human health (IPCC 2014). However, traditional approaches can hardly handle this nonlinear behavior; moreover, the analysis of hydrological systems at the large scale, even globally, requires dealing with large volumes of real-time data. There is great demand for the development of models to evaluate, predict, and optimize the performance of complex hydrological systems whose behavior is characterized by strong nonlinearity. AI could help to understand the complex relationships between the Earth’s climate, soil, and water processes. With its ability to learn from databases, make predictions, and automate decision-making processes, AI presents a compelling solution to the multifaceted challenges of climate, soil, and water resources management (Schmidhuber 2015). Therefore, it is expected that AI could potentially improve the forecasting of environmental parameters at the field and regional levels, such as soil, water, and climate (Reichstein et al. 2019).

In recent years, deep learning (DL) has shown great potential for processing massive data and solving large-scale nonlinear problems (Goodfellow et al. 2016). With their ability to capture complex nonlinear relationships and temporal dependencies in data, these models are well-suited for predicting hydrological variables (Shen 2018). With the right database, advanced AI methods can be employed to predict key meteorological variables. Atmospheric factors, particularly temperature and precipitation, play a significant role in predicting streamflow, groundwater level, soil moisture, and soil temperature (Beven 2011). The main goal of this publication is to introduce new AI techniques that can predict all environmental parameters of climate, soil, and water.

What is machine learning (ML)?

Machine learning (ML), a subfield of artificial intelligence, focuses on enabling computers to derive insights and make predictions from data without explicit hard-coded instructions. In hydrologic science, ML techniques are harnessed to model and predict complex water-related processes—such as streamflow, groundwater recharge, soil moisture dynamics, and water quality—by uncovering intricate patterns within large and often highly variable datasets. Unlike traditional hydrologic modeling that relies heavily on deterministic equations derived from physical principles, ML approaches can integrate diverse data sources (e.g., weather records, land-use information, topographic metrics, remote sensing imagery, and historical water resource measurements) to construct flexible, data-driven models.

These models learn from historical observations, adapt to changing conditions, and often improve in accuracy as more data become available. This is particularly useful for hydrologic forecasting in regions with limited observational data or rapidly shifting climatic conditions. By distilling complexity into relationships between inputs (like precipitation, temperature, and watershed characteristics) and outputs (such as streamflow or groundwater levels), ML provides a complementary tool to traditional methods, offering improved predictive capabilities, enhanced understanding of system behavior, and support for more informed decision-making in water resource management.

Traditional hydrological models, which are based on deterministic equations derived from physical principles, often have limitations in representing the nonlinear and highly variable behavior of environmental systems (Beven 2011; Clark et al. 2017). In contrast, data-driven models—particularly those based on machine learning and deep learning—can identify complex patterns in large and heterogeneous datasets without relying on predefined assumptions (Shen 2018; Reichstein et al. 2019). These models are well-suited for integrating multiple data sources, including remote sensing, meteorological observations, and land-use data, and can adapt to non-stationary conditions (Nearing et al. 2021). Consequently, they frequently demonstrate improved predictive performance over conventional methods, particularly in regions with limited data availability or where hydrological conditions are subject to rapid change (Mosavi et al. 2018; Kratzert et al. 2019). These capabilities make AI-based models a valuable addition to existing hydrological forecasting frameworks.

What is deep learning (DL)?

Deep learning (DL), a specialized branch of machine learning, utilizes multi-layered neural networks—computational models inspired by the human brain that consist of interconnected nodes (or "neurons") organized in layers—to model and interpret complex, nonlinear relationships within large hydrological datasets. In hydrologic science, DL techniques are employed to enhance the prediction and analysis of key water-related processes such as streamflow, groundwater levels, soil moisture, and water quality. By integrating diverse data sources—including meteorological records, remote sensing imagery, and land-use information—DL models can automatically extract relevant features and uncover intricate patterns that traditional methods may miss. This capability allows for more accurate and timely forecasts, improved understanding of hydrological dynamics, and better-informed water resource management decisions. Additionally, DL's ability to handle vast and varied datasets makes it particularly valuable in regions with limited observational data or rapidly changing environmental conditions, thereby advancing the effectiveness and resilience of water resource forecasting systems.

Case Study in Florida

Machine Learning in Forecasting Water Resources

With available data from a Florida hydrology database, research has been initiated to apply advanced AI methods for forecasting the most consequential hydrological fields (i.e., groundwater level and surface water discharge).

Overview of DL Models Used in Forecasting Water Resources in Florida

Several types of neural network models have been applied to predict and analyze water time series data. General recurrent neural networks (RNN), particularly well-suited for processing sequential data such as time series, were utilized to predict changes in water levels over time based on past measurements. Feedforward neural networks were employed to establish direct predictions from meteorological inputs, useful in scenarios where historical data patterns directly inform future conditions. Lastly, transformer models, known for their ability to handle complex relationships within data, were utilized to enhance predictions by focusing on the intricate dependencies and patterns in water level fluctuations. Together, these models operated as robust tools to accurately forecast water-related trends, which are crucial for effective water resource management.

Forecasting River Discharge and Groundwater Levels in Florida Using AI Methods

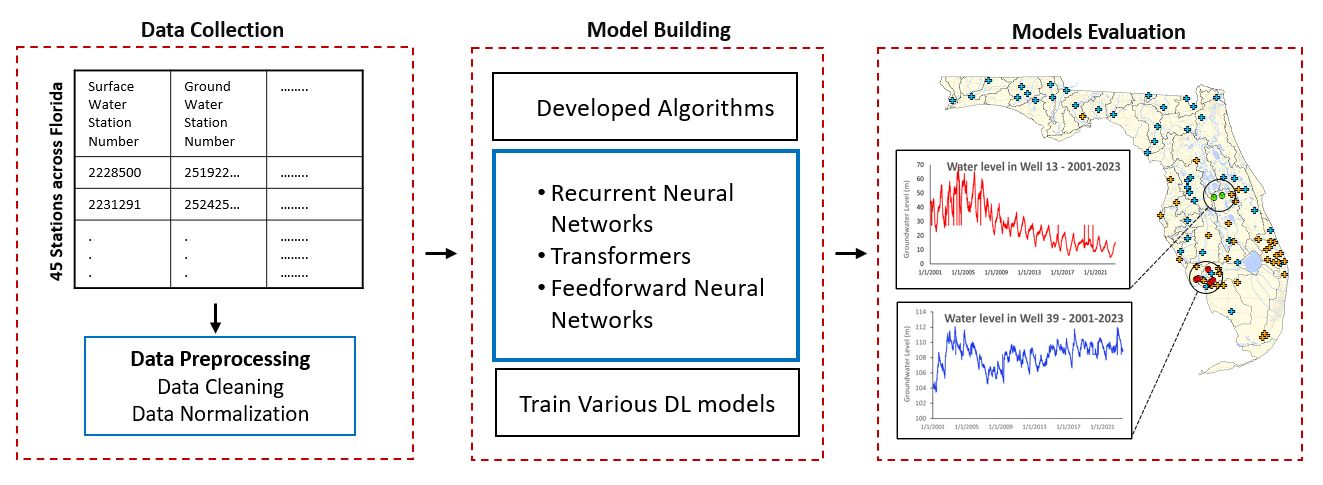

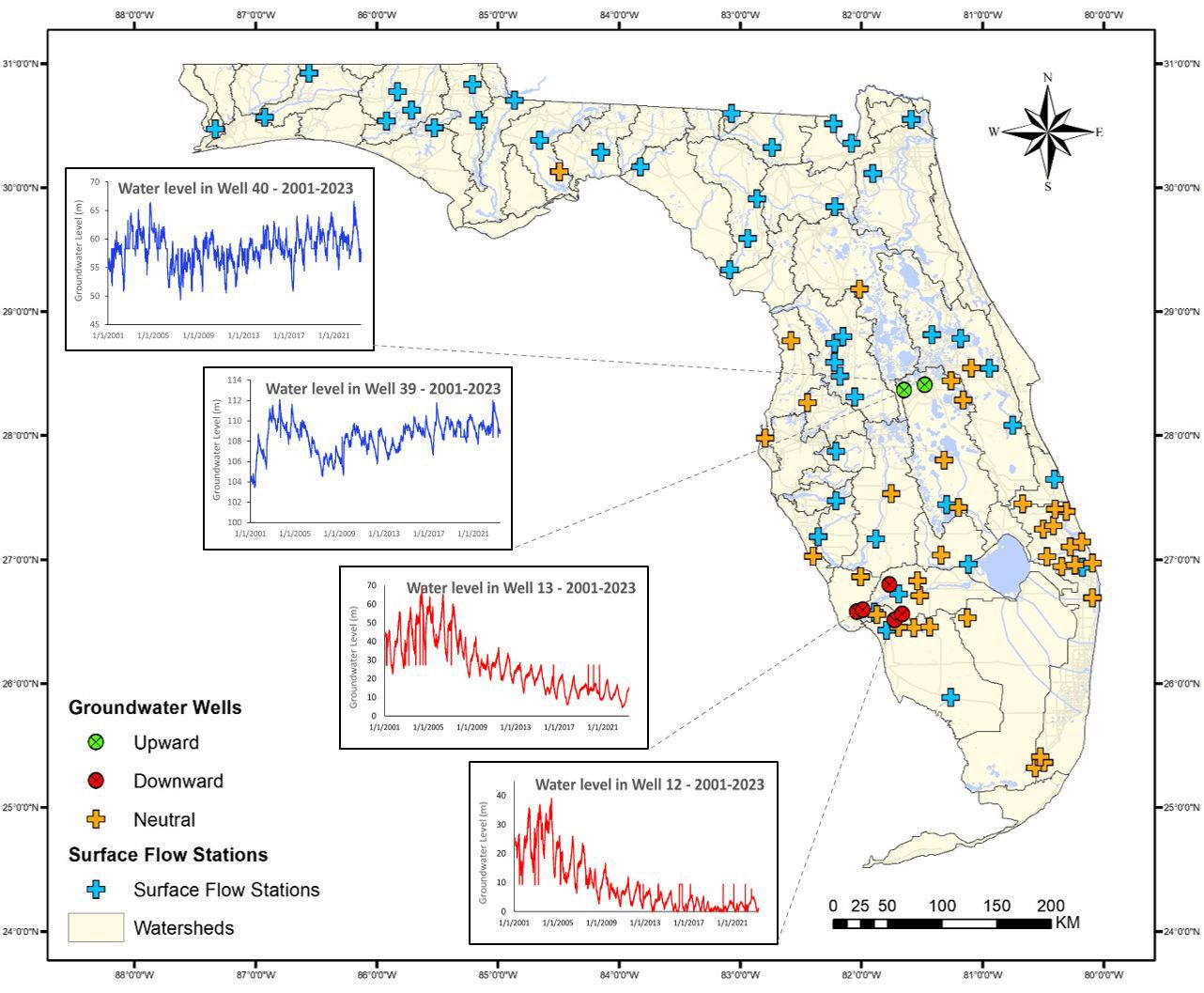

This study utilized daily records from the United States Geological Survey covering 23 years (2001–2023) from 45 surface water discharge stations and 45 groundwater level stations. Data preprocessing involved several essential steps to ensure data quality and consistency. Missing values were handled using linear interpolation, where the missing data points were estimated based on the values of the nearest known points, maintaining the continuity of the dataset (Figure 1). Additionally, units were standardized for consistency: groundwater levels were converted from feet to meters, and surface water discharge values were converted from cubic feet per second to cubic meters per second. The dataset was then split chronologically into training and testing sets using an 80:20 ratio, with 80% of the data allocated for model training and 20% reserved for testing to evaluate model performance. While prior knowledge of these steps is not essential for understanding the results, readers interested in more details can refer to standard resources on data preprocessing techniques in AI applications (Maharana et al. 2022). Additionally, recent advancements in large language models now offer accessible and user-friendly tools, enabling even non-experts to handle many data preprocessing tasks efficiently (Zhang et al. 2024).

This research evaluated various deep learning models for predicting daily surface water discharge and groundwater levels in Florida. The evaluated models include specific architectures under the categories of recurrent neural networks (RNNs), feedforward neural networks, and transformer models. An LSTM, a specialized type of RNN, was used for its effectiveness in capturing sequential dependencies in hydrological time-series data. The LSTM model was updated to include a layer size of 512 neurons (or “units”), aligning its representational capacity with the other models. For feedforward neural networks, NBEATS and NHITS were employed, with NHITS demonstrating strength in handling multiscale hierarchical patterns. NHITS was further modified to have a hidden size of 512 neurons, ensuring a fair comparison with other models. NBEATS retained its original architecture, featuring two stacks of three fully connected layers with 512 neurons per layer, optimized for trend and seasonal pattern recognition. Among transformer-based models, Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) and Informer were utilized for their ability to process sequential data efficiently. TFT was configured with a hidden size of 512 neurons and 8 attention heads, while retaining its original feedforward dimension of 128, making it slightly less complex than Informer. Informer featured an encoder-decoder structure with 2 encoder layers, 512 neurons, 8 attention heads, and 2,048 feedforward dimensions, optimized for long-sequence forecasting using sparse self-attention mechanisms. Regularization was applied consistently across all models using dropout or weight decay to prevent overfitting. Additionally, all models were trained for 100 epochs with early stopping, a batch size of 128, and optimization using Adam or equivalent optimizers with similar learning rates. These adjustments ensured that each model operated with comparable resources, allowing for a balanced evaluation of their performance on hydrological forecasting tasks. Collectively, these models operated as robust tools to accurately forecast water-related trends, which are crucial for effective water resource management.

The preliminary results demonstrate that DL models consistently performed well across all stations, effectively capturing the temporal dynamics of both surface water and groundwater. Among the evaluated models, NHITS emerged as the most robust, delivering superior accuracy in the majority of the 45 groundwater and 45 surface water stations analyzed, often outperforming other models by significant margins. TFT ranked as the second-best model, outperforming NHITS in 12 surface water stations and 6 groundwater stations. To further demonstrate the practical application of the models, NHITS, as the top-performing model, was used to forecast surface water discharge and groundwater levels for the next 3, 6, 9, and 12 months. The forecasting results highlight the capability of NHITS and other models to accurately predict future trends. These important trends include potential drops in the groundwater levels of some areas that could affect water availability for farming, as well as increases in river discharge and the groundwater levels of other areas that might lead to flooding (Figure 2).

Conclusions

Increasing population and extreme weather events are expected to make water resources forecasting more important due to more frequent and intense droughts, heatwaves, and large storms. This publication aims to introduce the new advanced machine learning approaches applied to water resources and to describe a case study of applications in Florida. Several deep learning techniques have been introduced for hydrological applications in Florida. Among these, transformers represent a significant advancement in AI, demonstrating their potential to revolutionize hydrology modeling. This makes them a game changer in predicting daily surface water discharge and groundwater levels.

These comparisons highlight each model's varying capabilities in handling Florida's complex hydrological data, contributing valuable insights to the development of accurate and reliable hydrological forecasting models, which are crucial for sustainable water resource management in the face of changing climate conditions.

With sufficient data and computational resources, AI-based models can identify areas susceptible to flooding and regions likely to experience water shortages. Despite their strong predictive performance, AI models remain limited in their ability to represent hydrologic processes, management scenarios, and system dynamics. Therefore, combining AI models with traditional physics-based hydrologic models is recommended to improve forecasting under future climate conditions. Large-scale implementation will require continued advances in Earth-observation datasets (e.g., upcoming satellite missions), improved retrieval algorithms, integrated modeling frameworks, and cloud-based processing environments (Brocca et al. 2024). In the coming years, the complementary use of AI and physics-based modeling is expected to enhance hydrologic simulations and forecasting, supporting informed decision-making at regional and statewide scales.

References

Beven, K. J. 2011. Rainfall-Runoff Modelling: The Primer. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119951001

Botache, E. M., and S. Guzman. 2024. “How to Identify If Your Time Series Inputs Are Adequate for AI Applications: Assessing Minimum Data Requirements in Environmental Analyses: AE594, 1/2024.” EDIS 2024 (1). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-ae594-2024

Brocca L. , S. Barbetta, S. Camici, et al. 2024. “A Digital Twin of the Terrestrial Water Cycle: A Glimpse into the Future Through High-Resolution Earth Observations.” Frontiers in Science 1. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsci.2023.1190191

Campbell, S. I., D. B. Allan, A. M. Barbour, et al. 2021. “Outlook for Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning at the NSLS-II.” Machine Learning: Science and Technology 2: 013001. https://doi.org/10.1088/2632-2153/abbd4e

Choi, D., O. Mirbod, U. Ilodibe, and S. Kinsey. 2023. “Understanding Artificial Intelligence: What It Is and How It Is Used in Agriculture: AE589, 10/2023.” EDIS 2023 (6). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-ae589-2023

Clark, M. P., B. Nijssen, J. D. Lundquist, et al. 2015. “A Unified Approach for Process‐Based Hydrologic Modeling: 1. Modeling Concept.” Water Resources Research 51 (4): 2498–2514. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015WR017198

Goodfellow, I., Y. Bengio, and A. Courville. 2016. Deep Learning. The MIT Press.

Hannah, D. M., S. Demuth, H. V. Lanen, et al. 2011. “Large-Scale River Flow Archives: Importance, Current Status and Future Needs.” Hydrological Processes 25 (7): 1191–1200. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.7794

IPCC. 2014. Climate Change 2014—Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Regional Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by C. B Field, V.R. Barros, D. J. Dokken et al. Cambridge University Press.

Kratzert, F., D. Klotz, G. Shalev, G. Klambauer, S. Hochreiter, and G. Nearing. 2019. “Towards Learning Universal, Regional, and Local Hydrological Behaviors via Machine Learning Applied to Large-Sample Datasets.” Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 23 (12): 5089–5110. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-23-5089-2019

Maharana, K., S. Mondal, and B. Nemade. 2022. “A Review: Data Pre-Processing and Data Augmentation Techniques.” Global Transitions Proceedings 3 (1): 91–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gltp.2022.04.020

McAfee, A., and E. Brynjolfsson. 2017. Machine, Platform, Crowd: Harnessing Our Digital Future. WW Norton & Company.

Mosavi, A., P. Ozturk, and K. W. Chau. 2018. “Flood Prediction Using Machine Learning Models: Literature Review.” Water 10 (11): 1536. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10111536

Nearing, G. S., F. Kratzert, A. K. Sampson, et al. 2021. “What role does hydrological science play in the age of machine learning?” Water Resources Research 57 (3): e2020WR028091. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020WR028091

Reichstein, M., G. Camps-Valls, B. Stevens, et al. 2019. “Deep Learning and Process Understanding for Data-Driven Earth System Science.” Nature 566: 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-0912-1

Russell, S. J., and P. Norvig. 2016. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach. 3rd edition. Pearson.

Schmidhuber, J. 2015. “Deep Learning in Neural Networks: An Overview.” Neural Networks 61: 85–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2014.09.003

Shen, C. 2018. “A Transdisciplinary Review of Deep Learning Research and Its Relevance for Water Resources Scientists.” Water Resources Research 54 (11): 8558–8593. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018WR022643

Zhang, S., Z. Huang, and E. Wu. 2024. “Data Cleaning Using Large Language Models.” 2025 IEEE 41st International Conference on Data Engineering Workshops (ICDEW): 28–32.