Introduction

This cultivar of augar maple grows rapidly to 50 feet tall at maturity in a landscape. It grows about one foot each year in most soils but is sensitive to reflected heat, and to drought, turning the leaves brown (scorch) along their edges. Despite some resistance, leaf scorch from dry soil is often evident in areas where the root system is restricted to a small soil area, such as a street tree planting. It is more drought-tolerant in open areas where the roots can proliferate into a large soil space.

Credit: Ed Gilman

General Information

Scientific name: Acer saccharum

Pronunciation: AY-ser sack-AR-rum

Common name(s): 'Green Mountain' sugar maple

Family: Aceraceae

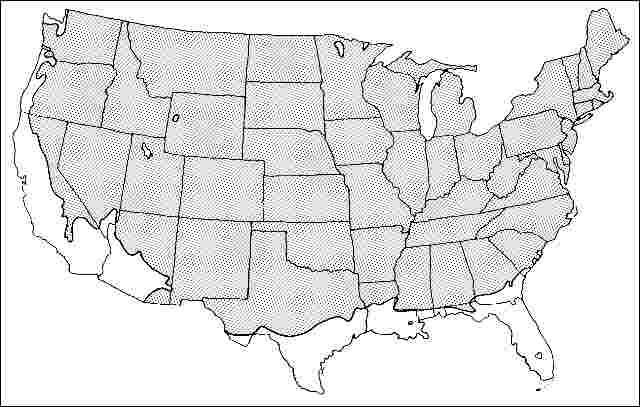

USDA hardiness zones: 3A through 8A (Fig. 2)

Origin: native to North America

Invasive potential: little invasive potential

Uses: street without sidewalk; screen; shade; tree lawn > 6 ft. wide; specimen

Availability: not native to North America

Description

Height: 40 to 60 feet

Spread: 35 to 50 feet

Crown uniformity: symmetrical

Crown shape: oval

Crown density: dense

Growth rate: moderate

Texture: medium

Foliage

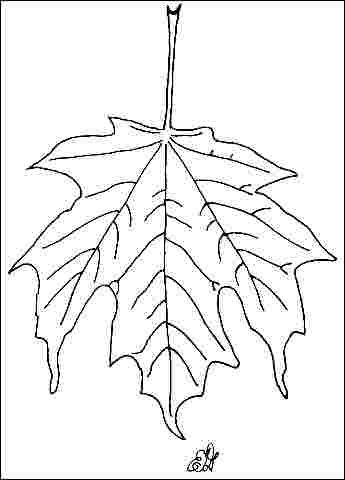

Leaf arrangement: opposite/subopposite (Fig. 3)

Leaf type: simple

Leaf margin: undulate, lobed

Leaf shape: star-shaped

Leaf venation: palmate

Leaf type and persistence: deciduous

Leaf blade length: 2 to 4 inches, 4 to 8 inches

Leaf color: green

Fall color: red, orange

Fall characteristic: showy

Flower

Flower color: green

Flower characteristics: not showy

Fruit

Fruit shape: elongated

Fruit length: 1 to 3 inches

Fruit covering: dry or hard

Fruit color: brown

Fruit characteristics: attracts squirrels/mammals; not showy; fruit/leaves not a litter problem

Trunk and Branches

Trunk/bark/branches: branches droop; showy; typically one trunk; thorns

Pruning requirement: little required

Breakage: resistant

Current year twig color: brown

Current year twig thickness: thin, medium

Wood specific gravity: 0.63

Culture

Light requirement: full sun, partial sun or partial shade, shade tolerant

Soil tolerances: clay; sand; loam; acidic; alkaline; well-drained

Drought tolerance: moderate

Aerosol salt tolerance: none

Other

Roots: not a problem

Winter interest: yes

Outstanding tree: yes

Ozone sensitivity: unknown

Verticillium wilt susceptibility: susceptible

Pest resistance: resistant to pests/diseases

Use and Management

The dense, highly branched crown creates dense shade and will prevent good lawn growth. Branches are usually well attached to trunks, resulting in a low branch failure rate. The main ornamental feature of the tree is the brilliant red, yellow, or orange fall color that develops in the cooler part of its range. The yellows are more prominent in the South. The tree transplants fairly easily but may develop girdling roots that can reduce growth, or in extreme cases kill the tree.

The limbs of sugar maple are usually strong and not susceptible to wind damage. The bark forms attractive bright gray plates, which stand out especially during the winter. Roots are often shallow and reach the surface at an early age, even in sandy soil. Plant in an area where grass below it will not need to be mowed so the roots will not be damaged by the mower. A variety of birds use the tree for food, nesting, and cover, and the fruits are especially popular with squirrels.

Growing in full sun or shade, sugar maple will tolerate a wide variety of soil types (except compacted soil) but is not salt-tolerant. Established trees look better when given some irrigation during dry weather, particularly in the South. In the South, many leaves remain in the central portion of the canopy for much of the winter, giving the tree a somewhat unkempt appearance. Sugar maples are not recommended for the Dallas area, in many cases due to alkaline soils causing chlorosis. Sensitivity to compaction, heat, drought, and road salt limit usage of sugar maple for urban street plantings, but it is still recommended for parks and other areas away from roads where soil is loose and well-drained. Black maple, a similar species, is more tolerant of heat and drought.

Nurseries may offer one or several other cultivars of sugar maple: 'Bonfire'—brilliant orange-red fall color; 'Endowment Columnar'—50 feet tall, columnar form, red and yellow fall color; 'Globosum'—a slow grower with a dense round crown and a mature height of about 10 feet; 'Goldspire'—dense, compact, pyramidal form, gold fall color; 'Majesty'—ovate form, resistant to frost crack and sun scald; 'Newton Sentry'—upright growth habit; 'Sweet Shadow'—cut leaves; 'Temple's Upright'—an upright growth habit.

Pests

Leaf stalk borer and petiole borer cause the same type of injury. Both insects bore into the leaf stalk just below the leaf blade. The leaf stalk shrivels, turns black, and the leaf blade falls off. The leaf drop may appear heavy but serious injury to a healthy tree is rare.

Gall mites stimulate the formation of growths or galls on the leaves. The galls are small but can be so numerous that individual leaves curl up. The most common gall is bladder gall mite found on Silver Maple. The galls are round and at first green but later turn red, then black, then dry up. Galls of other shapes are seen less frequently on other types of maples. Galls are not serious, so chemical controls are not needed.

Crimson erineum mite is usually found on silver maple and causes the formation of red fuzzy patches on the lower leaf surfaces. The problem is not serious so control measures are not suggested.

Aphids infest maples, usually Norway maple, and may be numerous at times. High populations can cause leaf drop. Another sign of heavy aphid infestation is honey dew on lower leaves and objects beneath the tree. Aphids are controlled by spraying or they may be left alone. If not sprayed, predatory insects will bring the aphid population under control.

Scales are an occasional problem on maples. Perhaps the most common is cottony maple scale. The insect forms a cottony mass on the lower sides of branches. Scales are usually controlled with horticultural oil. Scales may also be controlled with well-timed sprays to kill the crawlers.

If borers become a problem it is an indication the tree is not growing well. Controlling borers involves keeping trees healthy. Chemical controls of existing infestations are more difficult. Proper control involves identification of the borer infesting the tree then applying insecticides at the proper time.

Diseases

Anthracnose is more of a problem in rainy seasons. The disease resembles, and may be confused with, a physiological problem called "scorch". The disease causes light brown or tan areas on the leaves. Anthracnose may be controlled by fungicides sprayed on as leaves open in the spring. Additional sprays may be needed. The disease is most common on sugar and silver maples and boxelder. Other maples may not be affected as severely. Sprays may need to be applied by a commercial applicator having proper spray equipment.

Verticillium wilt symptoms are wilting and death of branches. Infected sapwood will be stained a dark or olive green, but staining can't always be found. If staining can not be found, do not assume the problem is not verticillium wilt. Severely infected trees probably can't be saved. Lightly infected trees showing only a few wilted branches may be pulled through. Fertilize and prune lightly infected trees. This treatment will not cure the problem but may allow the tree to outgrow the infection. Girdling roots will cause symptoms that mimic verticillium wilt.

Girdling roots grow around the base of the trunk rather than growing away from it. As both root and trunk increase in size, the root chokes the trunk. Girdling roots are detected by examining the base of the trunk. The lack of trunk flare at ground level is a symptom. The portion of the trunk above a girdling root does not grow as rapidly as the rest so may be slightly depressed. The offending root may be on the surface or may be just below the sod. The tree crown shows premature fall coloration and death of parts of the tree in more serious cases. If large portions of the tree have died it may not be worth saving. Girdling roots are functional roots so when removed a portion of the tree may die. When the girdling root is large the treatment is as harmful as the problem. After root removal, follow-up treatment includes watering during dry weather. The best treatment for girdling roots is prevention by removing or cutting circling roots at planting or as soon as they are detected on young trees.

Scorch occurs during periods of high temperatures accompanied by wind. Trees with diseased or inadequate root systems will also show scorching. When trees do not get enough water they scorch. Scorch symptoms are light brown or tan dead areas between leaf veins. The symptoms are on all parts of the tree or only on the side exposed to sun and wind. Scorching due to dry soil may be overcome by watering. If scorching is due to an inadequate or diseased root system, watering may have no effect.

Nutrient deficiency symptoms are yellow or yellowish-green leaves with darker green veins. The most commonly deficient nutrient on maple is manganese. Implanting capsules containing a manganese source in the trunk will alleviate the symptoms. Test soil samples to determine if the soil pH is too high for best manganese availability. Plants exposed to weed killers may also show similar symptoms.

Tar spot and a variety of leaf spots cause some concern among homeowners but are rarely serious enough for control.