Introduction

Growing up to 80 feet tall with a 50- to 60-foot spread, Texas red oak forms a stately tree with a narrow, rather dense rounded canopy. This oak is similar to the Shumard oak. The crown spreads with age becoming round at maturity. The 4- to eight8ly dark green during most of the year, Texas red oak puts on a vivid display of brilliant red to red-orange fall and winter foliage, providing a dramatic landscape statement. Fall and winter coloration varies from year to year in USDA hardiness zones 8 and 9. During the winter the bare tree provides interesting branching patterns. The 1.5-inch-wide acorns are surrounded by a shallow, enclosing cup and are popular with wildlife.

Credit: Ed Gilman, UF/IFAS

General Information

Scientific name: Quercus texana

Pronunciation: KWERK-us teck-SAY-nuh

Common name(s): Texas red oak, Texas oak

Family: Fagaceae

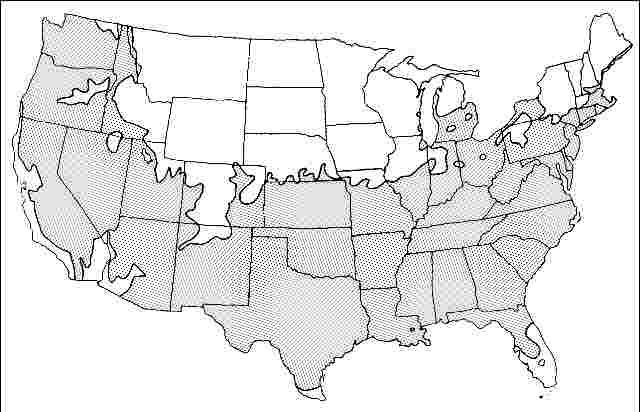

USDA hardiness zones: 5B through 9A (Fig. 2)

Origin: native to North America

Invasive potential: little invasive potential

Uses: reclamation; street without sidewalk; shade; specimen; parking lot island > 200 sq ft; tree lawn > 6 ft wide; urban tolerant; highway median

Availability: somewhat available, may have to go out of the region to find the tree

Description

Height: 30 to 75 feet

Spread: 25 to 50 feet

Crown uniformity: symmetrical

Crown shape: round, oval

Crown density: moderate

Growth rate: fast

Texture: coarse

Foliage

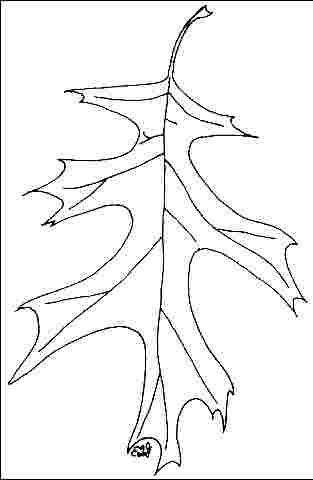

Leaf arrangement: alternate (Fig. 3)

Leaf type: simple

Leaf margin: parted, lobed

Leaf shape: obovate, elliptic (oval)

Leaf venation: pinnate

Leaf type and persistence: deciduous

Leaf blade length: 4 to 8 inches

Leaf color: green

Fall color: red, orange

Fall characteristic: showy

Flower

Flower color: brown

Flower characteristics: not showy

Fruit

Fruit shape: round, oval

Fruit length: .5 to 1 inch

Fruit covering: dry or hard

Fruit color: brown

Fruit characteristics: attracts squirrels/mammals; not showy; fruit/leaves a litter problem

Trunk and Branches

Trunk/bark/branches: branches droop; not showy; typically one trunk; thorns

Pruning requirement: needed for strong structure

Breakage: resistant

Current year twig color: brown

Current year twig thickness: medium

Wood specific gravity: unknown

Culture

Light requirement: full sun

Soil tolerances: clay; sand; loam; alkaline; acidic; well-drained

Drought tolerance: high

Aerosol salt tolerance: none

Other

Roots: not a problem

Winter interest: yes

Outstanding tree: yes

Ozone sensitivity: unknown

Verticillium wilt susceptibility: resistant

Pest resistance: resistant to pests/diseases

Use and Management

Texas red oak has become popular in some areas but is utilized sparingly in others. It deserves wider use in most parts of its range due to urban adaptability. Planted on 30- to 40-foot-centers, it will form a closed canopy over a two-lane street in 20- to 25-years with good growing conditions.

It makes a good street tree after some initial pruning to develop a central leader. Several leaders often develop in the nursery and when they are removed to develop one leader, the tree often looks very open and bare. Although this may be somewhat undesirable from an aesthetic standpoint, it creates a stronger tree which will provide a much longer service life than a multiple-leadered tree. The tree "fills in" as it grows older, forming a coarsely-branched, open interior. Once trained into a central leader this tree will require less pruning than live oak or pin oak, and may, therefore, require less maintenance as an urban tree. But it will not live as long as live oak. Branches are more upright and will not grow down toward the ground as will live, water, and laurel oak. Like other oaks, care must be taken to develop a strong branch structure early in the life of the tree. Be sure that main branches remain less than about half the diameter of the trunk to ensure proper development and longevity in the landscape. Be sure that these are removed periodically so that only one trunk remains.

A native of Central Texas on alkaline and slightly acidic soil, Texas red oak grows well in full sun on a wide variety of soils. Although it prefers moist, rich soil where it will grow rapidly, it will tolerate drier locations. It is highly stress-tolerant and will endure urban conditions quite well, including high pH soil. It appears to be well-adapted to clay soil, even those which are poorly drained.

Mites and occasionally root rot on prolonged wet soil are the major pests. Oak wilt will kill Texas red oak and is of particular concern in Texas.

Pests

Usually no pests are serious.

Galls cause homeowners much concern. There are many types and galls can be on the leaves or twigs. Most galls are harmless so chemical controls are not suggested.

Scales of several types can usually be controlled with sprays of horticultural oil.

Aphids cause distorted growth and deposits of honeydew on lower leaves. On large trees, naturally-occurring predatory insects will often bring the aphid population under control.

Boring insects are most likely to attack weakened or stressed trees. Newly planted young trees may also be attacked. Keep trees as healthy as possible with regular fertilization and water during dry weather.

Many caterpillars feed on oak. Large trees tolerate some feeding injury without harm. Trees repeatedly attacked, or having some other problem, may need spraying. Tent caterpillars form nests in trees then eat the foliage. The nests can be pruned out when small. Where they occur, gypsy moth caterpillars are extremely destructive on oaks.

Twig pruner causes twigs to drop off in the summer. The larvae ride the twig to the ground. Rake up and destroy fallen twigs.

Lace bugs suck juices from leaves causing them to look dusty or whitish gray.

Leaf miners cause brown areas in leaves. To identify leaf miner injury tear the leaf in two across the injury. If the injury is due to leaf miner, upper and lower leaf surfaces are separate and black insect excrement will be seen.

Diseases

Usually no diseases are serious.

Anthracnose may be a serious problem in wet weather. Infected leaves have dead areas following the midrib or larger veins. These light brown blotches may run together and, in severe cases, cause leaf drop. Trees of low vigor, repeatedly defoliated, may die. Trees defoliated several years in a row may need spraying, to allow the tree to recover.

Canker diseases attack the trunk and branches. Keep trees healthy by regular fertilization. Prune out diseased or dead branches.

Leaf blister symptoms are round raised areas on the upper leaf surfaces causing depressions of the same shape and size on lower leaf surfaces. Infected areas are yellowish-white to yellowish-brown. The disease is most serious in wet seasons in the spring but it does not need to be treated.

A large number of fungi cause leaf spots but are usually not serious. Rake up and dispose of infected leaves.

Powdery mildew coats leaves with white powdery growth.

Oak wilt is a fatal disease beginning with a slight crinkling and paling of the leaves. This is followed by leaf wilting and browning of leaf margins then working inward. The symptoms move down branches toward the center of the tree. Cut down and destroy infected trees. The disease may be spread by insects or pruning tools. The disease appears to infect red, black, and live oaks particularly. Avoid pruning in late spring and early summer in areas where oak wilt is present. Dormant or summer pruning is best.

Shoestring root rot attacks the roots and once inside moves upward, killing the cambium. The leaves on infected trees are small, pale, or yellowed and fall early. There is no practical control. Healthy trees may be more resistant than trees of low vigor.