Introduction

The goal of the "Building for Birds" online tool is to provide decision makers with a way to evaluate different development scenarios and how they affect habitat for different species of forest birds that can use fragmented areas. This evaluation tool is most useful for small developments or developments in already fragmented landscapes.

The tool is designed for use when no opportunity is available to conserve large forest areas of 125 acres or more within a proposed development. Developers are sometimes reluctant to conserve trees and forest fragments in subdivided residential/commercial areas because it costs time and money, but there is value in this conservation effort for many different species of forest birds—not to mention future homeowners waking to birdsong in the mornings. Forest fragments and trees conserved in built areas can serve as breeding, wintering, and stopover habitat for a variety of species.

Many bird species use habitat in and around urban areas. The online tool calculates conserved bird habitat scores based on forest fragments and tree canopy cover conserved for a particular development design. To determine bird habitat scores as a result of different development designs, simply enter the amount of conserved forest fragments and conserved tree canopy cover in built areas. Using these inputs, the tool generates a report for a particular scenario, containing a score for each of the bird habitat categories and a list of birds that could be found in each of these habitats. The tool can be found at http://wec.ifas.ufl.edu/buildingforbirds/web/home.html . Below, we describe how this tool can assist with preserving stopover sites for migrating birds.

Migrating Birds

Long-Distance Migrants

In and around urban areas, forest fragments could be used by an important group of birds called Neotropical migrants (Figure 1). These long-distance migrants typically breed during the summer in the United States and Canada, and they migrate south to spend the winter months in Mexico, Caribbean islands, Central America, and South America (Figure 2). Note that although some individuals of a population of Neotropical migrants winter in the United States (e.g., some yellow warblers winter in south Florida), most winter south of the United States. Migrating species make the return trip in the spring back to their breeding grounds. Along the migration route, forest fragments in urban and rural areas can serve as stopover sites where migrants land for anywhere from a few days to a few weeks. These stopover sites provide crucial "rest stops" where Neotropical migrants rest and forage on their long journeys.

Credit: Audubon, www.audubon.org

On their breeding grounds, a few Neotropical migrants use forest edges and open woodlands and are not very sensitive to forest fragmentation (e.g., Baltimore oriole, Icterus galbula). However, many Neotropical migrants are sensitive to fragmentation (e.g., cerulean warbler, Setophaga cerulea) and typically only breed successfully in large patches of forest (greater than 100 acres). Birds that primarily breed in large forest patches are called interior forest specialists. These species are thought to be vulnerable in fragmented landscapes because they are area sensitive, typically build open-cup nests on or near the ground, lay relatively few eggs, and often do not nest again if a nest fails.

In fragmented landscapes containing agriculture and urban areas, a variety of nest predators and brood parasites are more abundant along the edges of forests. Nest predators include mammals and birds, such as raccoons, cats, skunks, blue jays, and crows. The main brood parasite is the brown-headed cowbird that lays eggs in a Neotropical migrant's nest, tricking the migrant parents into feeding and raising the cowbird chick instead of their own. Cowbirds and nest predators thrive in fragmented forest landscapes containing agriculture fields, pastures, and residential development.

Some interior forest specialists (e.g., Canada warbler, Cardellina Canadensis) breed in dense understory growth in the openings of large forests and use regenerating vegetation (caused by windfalls, fires, and clearcutting). Although they technically breed along edges, they do so in large forest patches, and they are thought to be vulnerable to the increased predation and cowbird parasitism common in forest edges found in fragmented landscapes where urban and agriculture areas are nearby. Overall, interior forest specialists are vulnerable to forest fragmentation and many populations of these species are declining and are in danger of extinction due to human modifications of the landscape.

Short- and Medium-Distance Migrants

Short- and medium-distance migrants are birds that breed in the United States and Canada and winter in the United States. Short-distance migrants move within their breeding range, whereas medium-distance migrants move south of their breeding range but still within the United States. Many of these species are considered both as year-round residents (they breed and winter in the same area) and short- and/or medium-distance migrants. The American robin (Turdus migratorius) is an example because a portion of the robin population breeds in Canada and migrates south to the United States during the winter. Other robins can be seen year-round in most states south of Canada, but of these, a portion of the population will migrate south during the winter, going across state lines. Florida is one state where robins do not breed but they can be found in Florida during the winter because some robins migrate there.

Sometimes, individuals in the same species can either be short/medium-distance or long-distance migrants. For example, cedar waxwings (Bombycilla cedrorum) are Neotropical migrants. Most of them are long-distance and spend the winter months in Central America and Caribbean islands, but a portion of the population is medium-distance and winters in Georgia, Texas, Florida, and other southern states of the United States.

Scoring Justification and Species List

Studies we encountered in our review of the literature have found that many Neotropical migrants, both migrants that breed in the interiors of large forests and migrants that breed in small forest patches and open woodlands, use small forest fragments as stopover sites. Thus, small forest fragments may not be appropriate as breeding habitat for many interior forest Neotropical migrant species but could serve as stopover habitat. Short/medium-distance migrants also use forest fragments as stopover sites. Some studies have indicated that Neotropical and short-distance migrants were found in early and late successional forest fragments. Therefore, we count both early and late successional forest patches as stopover habitat. Early successional forest fragments are defined here as 1) shrublands composed primarily of shrubs with some scattering of trees and grassland patches, and 2) very young forests primarily composed of planted pine saplings and/or pioneer species such as black cherry (Prunus sp.), trees that are 0–15 years old, and tree height is typically less than 30 ft. In late successional forest fragments, most of the trees that form the canopy are over 30 ft tall, including both relatively young forests with trees 15–50 years old and mature forests with trees 50 years old or older. (To be considered a forest fragment, the minimum size is 1 acre of forest. Any groupings of trees less than 1 acre do not count as forest fragments.)

From the scientific literature, we generated a list of migrant birds that were observed in small forest fragments during the spring and fall migration seasons, indicating these species could use small urban forest remnants as stopover habitat https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1WGlFiMlrhCd6fpTDoBSyAvKepXQAiMhzGb4CBSaeC3s/edit#gid=204625953. We included only forest birds that are in order Passeriformes (i.e., perching birds), Piciformes (i.e., woodpeckers), Apodiformes (hummingbirds), and Columbiformes (doves and pigeons); we excluded raptors, waterbirds, etc. from the lists. Because of study locations reported in the literature, this list does not cover all North American migrant species. In other words, bird species may be missing because they were not adequately studied. However, we suspect that any forest-dwelling migrant bird could use small forest fragments as stopover sites along its migration route.

A majority of the species were from studies that surveyed migrating species in one or several similar-sized, small forest fragments. These studies listed migrant bird species that used these patches during the fall or spring. They did not explicitly compare forest fragments of different sizes. However, a few studies conducted surveys across a range of small forest fragments, and these studies found that relatively larger forest fragments contained more Neotropical migrants (Cox 1988, Somershoe et al. 2004). Because of these studies, we gave more points for conserving relatively larger forest fragments, and we divided forest fragments into 5 patch-size categories (Table 1).

We note that the scores are only relative for one design versus another. A higher score on one site than another may indicate more individuals or bird species on that site, but a higher score on a given site does not necessarily indicate that a similar—or even a nearly identical—site will have a similarly high score. Habitat selection by wildlife is notoriously difficult to predict. There are many other variables, such as habitat quality and surrounding landscapes (e.g., whether the development located next to forest land or agricultural land). Thus, the scores do not translate into an exact measure of increased habitat that leads to an increase in the abundance or species richness of forest birds—e.g., if forest fragment cover were increased by 10%, then that would mean one would find 2 more birds per acre or an increase in species diversity by 10%. The tool only can be interpreted in this way: a higher score means that there is more available bird habitat on the site, and it could attract more individuals or more species if that design were adopted.

Scoring Examples

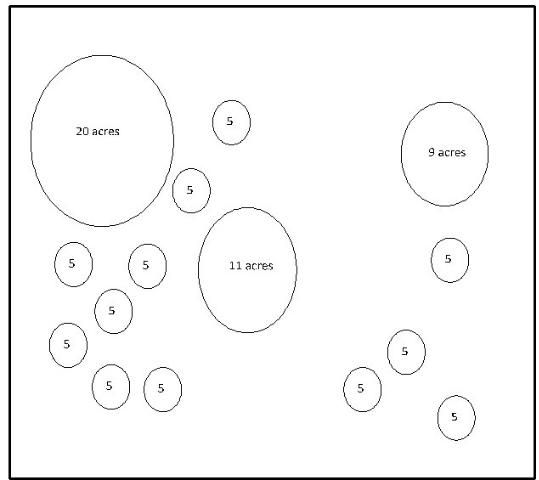

To score stopover habitat, start at the largest forest patch category (larger than 17 acres) and work your way down, counting each patch only once. Here, we give an example on how to score stopover habitat for a hypothetical development scenario. In this example, the developer has conserved forest patches of various acreages in the different size categories for a total of 100 acres (Figure 3). The total score for this scenario is 124 points (Table 2).

In order to count a forest patch (both early and late successional, as defined above), the area contained within the forest patch must be primarily composed of native trees and must be managed as natural habitat. In other words, a majority of the trees cannot be cultivated fruit trees or exotic trees, and the understory of the forest patch cannot contain mowed lawns and significant impervious surfaces (e.g., asphalt parking lots). In forest patches that have such human-made features and large areas of exotic trees, simply subtract the number of acres occupied by these artificial structures. The rationale here is that these types of heavily modified areas are lower-quality habitat for birds and would not typically support a diversity of species. However, for calculating the score of tree canopy conserved in the built matrix, do count the tree canopy cover in conserved areas that contain a significant amount of human modified landscapes such as mowed grass or rangeland for cattle. In some situations, land set aside that will be restored through planting or natural forest regeneration could also be counted.

If you have patches that are just under the category cutoffs, do not round up when placing into a category. For example, if 6 patches are measured at 4.9 acres each, these patches belong to in the category of 1 to 5 acres. The total number of acres conserved for this category is 6 X 4.9 acres = 29.4 acres. Here, you would round total number of acres conserved; in this case 29.4 acres is 29 acres conserved for this 1- to 5-acre category.

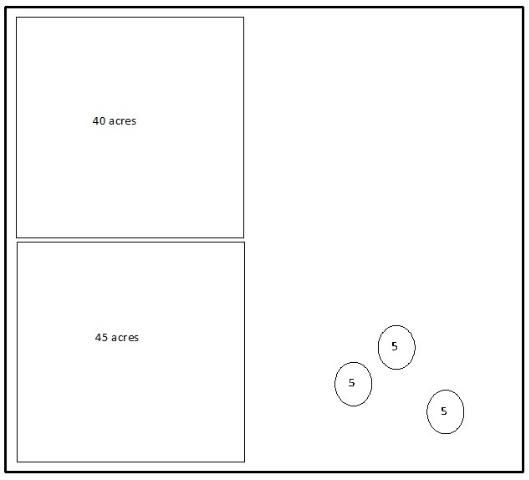

Improving a score: A developer can improve the score for stopover habitat by conserving larger patches of forest and/or by increasing the amount of forest conserved. In the aforementioned example, the developer could significantly improve the score by clustering the development and saving larger patches. For example, the development could build only on the east side of the property and conserve two larger patches on the west side (Figure 4). In this second scenario, 100 acres of forest patches are still conserved, but the total score is now 168 (Table 3). This is a 36% increase in the score for stopover habitat.

Determining Which Bird Species May Be Using the Forest Patches within a Development as Stopover Habitat

Answering this question takes a little investigation because the geographic location of your development may or may not be along the migratory route of a particular species. A list of migrant species that could use forest patches as stopover sites is found at https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1WGlFiMlrhCd6fpTDoBSyAvKepXQAiMhzGb4CBSaeC3s/edit#gid=204625953 (look at Overall Comparisons – Stopover in Forest Fragment). This link gives a list of migrant species that could use forest patches as stopover sites. Not all of these species will appear within a given development during a given migration, even if that development has a very high score. A development must be within the migratory route of a bird species for that bird to appear in the development. As an example, the cerulean warbler (Setophaga cerulea) breeds in the northern states of eastern United States, migrates through the southern states, and winters in South America (Figure 5). Thus, if your development is located in Indiana, you might see cerulean warblers in it because Indiana falls within the breeding range of the cerulean warbler. Spotting the birds would still be possible even if there are only small forest fragments in your development because although the birds will not use small forest fragments as nesting habitat (cerulean warblers are interior forest specialists), they might well use those forest fragments as stopover habitat during their migration. Developments in areas outside of the birds' breeding range, such as Georgia, can still host cerulean warblers using conserved forest fragments as stopover habitat. A development site located in the West would not have Cerulean warblers passing through no matter how high its preservation score because that area is outside the birds' migratory and breeding ranges.

Credit: www.allaboutbirds.org

For short-distance migrants, a site could serve as a breeding habitat, stopover habitat, and wintering habitat for the same species. For example, a site containing forest fragments in Indiana could have some robins residing there all year round, some that pass through the area and use the fragments as stopover habitat, and some that migrate to the area and overwinter there. For range maps of all the migrant birds, visit https://www.allaboutbirds.org.

Long-Term Functionality: Managing Conserved Habitat for Birds

Aside from conserving remnant forest fragments, several other strategies can improve the suitability of the forest fragments for bird habitat during the breeding/winter season. Most important is to maintain the quality of the habitat over the long term. Although we mentioned above that forest fragments overrun with exotics or artificial structures such as maintained turfgrass are lower-quality habitat, even natural forest fragments need to be managed appropriately over time. Typically, in urban/agriculture landscapes, forest fragments host a few invasive exotic plants. Further, invasive exotic vegetation planted in yards can escape and invade nearby forest areas. Developments with conserved forest fragments should have funding and a management plan and an educational strategy to engage residents in order to reduce/minimize impacts stemming from nearby urban areas. In particular, we recommend the following:

- Educational Signage Program: Because many impacts from nearby residential areas stem from individual homeowner decisions, we recommend raising awareness about these impacts and actions that would retain the biological integrity of the forest fragments and even enhance the habitat values of yards and neighborhoods. Installing neighborhood educational kiosks with environmental panels is one way to raise awareness. This type of education program can impact homeowner knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors (Hostetler et al. 2008). See neighborhood signage example at https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2015/06/14/how-can-we-engage-residents-to-conserve-urban-biodiversity-talk-to-them/, and https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/uw407.

- Management Plan and Funding: A management plan should address how the built and conserved areas will be managed to protect biodiversity. Create a funding source to help with the management of natural areas. Funds can be collected from homeowner association dues, home sales (even resales), property taxes, and the sale of large, natural areas to land trusts with some of the funds retained for management.

- Codes, Covenants, and Restrictions (CCRs): Implement CCRs that address environmental practices and long-term management of yards, homes, and neighborhoods. These CCRs should describe environmental features installed on lots and shared spaces and appropriate measures to maintain these. An example of an environmental CCR can be found at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/uw248.

For a species list that gives species identification, life history, results from three systematic reviews of the literature, and expected occurrence for 219 forest bird species recorded in studies conducted throughout the United States and Canada go to https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1WGlFiMlrhCd6fpTDoBSyAvKepXQAiMhzGb4CBSaeC3s/edit#gid=204625953. The Breeding Review columns show which species will breed in late or early successional forest fragments as well as which species are Interior-Forest Specialists (birds that do not breed in forest fragments). The Stopover Review column lists which species were observed in small forest fragments by studies conducted during the spring and fall migration seasons. The Built Environment Review columns show which species were observed within residential areas and gives the season of the observation. The Synanthropic Review columns show which species are synanthropic (urban-adapted species commonly found within the built matrix). Species are listed alphabetically by Order, Locality, and Common Name.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Renewable Resources Extension Act, UF/IFAS project 1000606.

Literature Cited

Cox, James. 1988. "The influence of forest size on transient and resident bird species occupying maritime hammocks of northeastern Florida." Florida Field Naturalist 16.2 (1988): 25–34.

Hostetler, M., E. Swiman, A. Prizzia, and K. Noiseux. 2008. "Reaching residents of green communities: Evaluation of a unique environmental education program." Appl. Environ. Edu. Commun. 7, 114–124.

Somershoe, Scott G., and C. Ray Chandler. 2004. "Use of oak hammocks by Neotropical migrant songbirds: the role of area and habitat." The Wilson Bulletin 116.1 (2004): 56–63.

In this development scenario, some large and small forest fragments are conserved. The total amount of forest conserved is 100 acres.

In this development scenario, most of the conserved forest is in two large patches. The total amount forest conserved is 100 acres.