Introduction

Credit: Audubon.

A variety of forest birds will use trees and shrubs in built areas (i.e., urban residential and commercial areas) as summer breeding sites and as foraging/shelter sites during the winter and spring/fall migration seasons. The purpose of this article is to explain the mechanics of an online evaluation tool that allows one to input different development plans and assess the extent of impacts to bird habitat by different designs. The tool can be found at https://wec.ifas.ufl.edu/buildingforbirds/web/home.html. Essentially the tool gives bird habitat scores for each development scenario after the user inputs the amounts of tree canopy cover remaining in residential areas after development. Thus, decision makers can explore different designs to determine which may be best in terms of bird habitat conservation.

For the purposes of evaluating different development scenarios, we restrict the online analysis to forest birds in the order Passeriformes (i.e., perching birds) and woodpeckers in order Piciformes because trees are important habitat for these birds during the breeding season. For example, woodpeckers are primary cavity nesters, often creating their own nesting cavities in trees. Secondary cavity nesters, such as the Carolina Chickadee, utilize natural holes in trees or cavities made by woodpeckers. Other species, such as the Northern Cardinal, make open cup nests in the branches of trees and bushes. We also included Apodiformes (hummingbirds) and Columbiformes (doves and pigeons). Thus, trees and shrubs are essential to birds in urban areas, allowing many species to acquire food, such as insects, fruits, tree sap, nectar, and seeds.

Not all birds can breed successfully in residential areas, which retain tree canopy cover but underneath contain buildings, roads, and lawns. Some birds, such as several species of Neotropical migrants (e.g., Cerulean warbler, Setophaga cerulea) are sensitive to forest fragmentation and typically only breed successfully in large patches of forest (e.g., greater than 100 acres). Birds that primarily breed in large forest patches are called interior forest specialists. It is hypothesized that these species are vulnerable in fragmented landscapes because they cannot successfully reproduce. Interior forest specialists are typically open-cup nesters on or near the ground, have small clutch sizes, and often do not nest again if a nest fails. In fragmented landscapes containing agriculture and urban areas, a variety of nest predators and brood parasites are more abundant along the edges of forests. Nest predators include mammals and birds, such as raccoons, cats, skunks, blue jays, and crows. The main brood parasite is the brown-headed cowbird, which lays eggs in a Neotropical migrant's nest and tricks the parents into feeding and raising the cowbird chick instead of their own. Cowbirds and nest predators thrive in fragmented forest landscapes containing agriculture fields, pastures, and residential development.

Overall, interior forest specialists are vulnerable to forest fragmentation and many populations of these species are declining and are in danger of extinction due to human modifications of the landscape. Note, some interior forest specialists (e.g., Canada Warbler, Cardellina canadensis) breed in dense understory growth in the openings of large forests and use regenerating vegetation (caused by windfalls, fires, and clearcutting). Although they technically breed along edges, they do so in large forest patches. They are thought to be vulnerable to forest edges found in fragmented landscapes where urban and agriculture areas are nearby because of increased predation and cowbird parasitism in fragmented landscapes containing agriculture and cities. This is important to understand, as some species will never successfully breed in residential areas. However, there is stopover habitat for interior forest specialists, because they can use small forest patches and residential areas as habitat during migration. A variety of species can use trees as habitat in residential areas during breeding, migrating, and wintering seasons. Every tree counts!

In the case of large development sites, where an opportunity exists to conserve patches of 125 acres or more, every effort should be made to conserve large patches and to have compact built areas. This is because large forest patches could serve as breeding areas for interior forest specialists. However, this document focuses on how to use the tool for evaluating residential areas where opportunities exist to conserve trees. Often, when land is subdivided, it costs time and money to conserve trees and other vegetation within residential/commercial areas, but there is value for many different species of forest birds. Many would say that the design and maintenance of trees in residential areas are not important because little bird habitat exists because of homes and roads in the neighborhoods. However, residential areas with extensive tree canopy cover can serve as breeding, wintering, and stopover habitat for a variety of species.

Scoring Justification and Species List

This evaluation tool should primarily be used to evaluate the relative worth of a different development plans for the same site. Residential areas with trees provide important habitat during breeding, migrating, and winter seasons. In fact, interior forest specialists, during the migration season, can use trees in built areas as stopover sites. From our review of the literature (Appendix A), we developed a list of bird species that could benefit from conservation of trees in residential areas https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1WGlFiMlrhCd6fpTDoBSyAvKepXQAiMhzGb4CBSaeC3s/edit#gid=204625953.

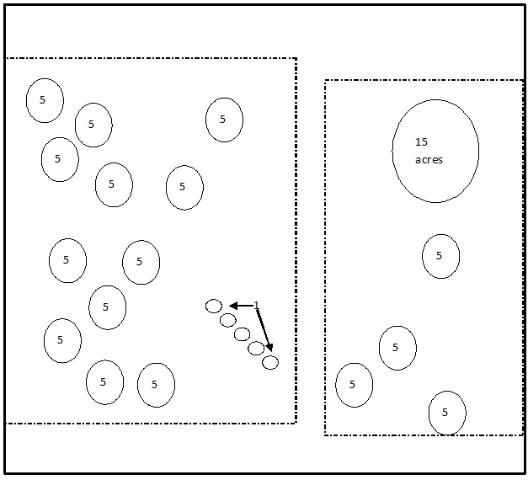

In determining the input variable, one looks within areas that are to be built and estimates the amount of tree canopy cover that will remain after construction. Based on the inputs from a user, the online tool assigns points based on the acreage of trees conserved in designated residential areas (Table 1). In this development scenario, some large and small amounts of tree canopy were conserved in the planned residential area. The total amount of forest conserved is 100 acres (80 acres occupied by sixteen 5-acre canopy patches, one 15-acre canopy patch, and 5 acres occupied by five 1-acre canopy patches).

Most studies were conducted during the breeding season and only a few studies were conducted during spring/fall migration. However, many of the birds that breed in built areas are short-distance migrants or are found year-round in a given location. For these species, we assumed that if they breed in residential/commercial areas, then they would also use these areas during the winter.

As indicated above, we only included forest birds that are in order Passeriformes (i.e., perching birds), Piciformes (i.e., woodpeckers), Apodiformes (hummingbirds), and Columbiformes (doves and pigeons); we excluded raptors, waterbirds, etc. from the lists. Because of study locations reported in the literature, this list does not cover all North American forest species. In other words, bird species may be missing because they were not adequately studied.

We note that the scores are only relative for one design versus another. When comparing across different sites, a higher score on one site versus another may indicate the potential of having more individual birds or more species of birds, but this does not necessarily mean this is true for every situation. Habitat selection by wildlife is notoriously difficult to predict. There are many other variables, such as habitat quality and surrounding landscapes (e.g., is the development situated by forest land or agriculture land?). Thus, the scores do not translate into exact predictions of numbers of individuals or numbers of species. The tool only can be interpreted in this way: a higher score means that there is more available bird habitat on the site and it could attract more individuals or more species if that design is adopted.

Scoring Examples

For scoring built-area habitat, one must first determine the areas that will be built, i.e., containing buildings and roads. Then, one has to realistically estimate which trees will be conserved and measure the remaining tree canopy cover across all built areas. Here, we give an example on how to score bird habitat within built areas for a hypothetical development scenario. In this example, the developer has conserved various amounts of tree canopy cover for a total of 100 acres (Figure 2). The total score for this scenario is 100 points (Table 2).

Which Bird Species May Be Using the Trees within Built Areas as Breeding/Wintering and Stopover Habitat?

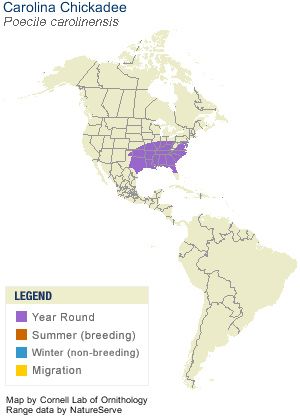

This question takes a little investigation because the geographic location of your development may or may not be in the breeding/wintering and stopover range of a particular species. A list of species that could use trees within the built areas can be found at https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1WGlFiMlrhCd6fpTDoBSyAvKepXQAiMhzGb4CBSaeC3s/edit#gid=204625953 (Look under Overall Comparisons – Breeds in Residential Area and Stopover in Residential Area). This link gives a list of species that could use trees within the built areas. Only a portion of these species could have the possibility of appearing within a development, depending if the location of the development overlaps with the breeding/wintering range of a species and/or is along the migration route. As an example, the Carolina Chickadee (Poecile carolinensis) primarily breeds in the southern states of eastern US (Figure 3). Thus, if a development is located in Wisconsin, it would not have the Carolina Wren. For range maps of all birds, visit https://www.allaboutbirds.org.

Credit: www.allaboutbirds.org

Long-Term Functionality: Managing Habitat for Birds in Built Areas

In addition to conserving tree canopy cover in built areas, several other factors play a role in the suitability of these areas as bird habitat. Most notably is whether the quality of the habitat is maintained over the long term. In addition to tree canopy cover, planting landscape areas with native vegetation can benefit birds by providing food and shelter. Further, the design and management of yards varies widely by individual homeowners. Even if a developer conserved tree canopy and installed native vegetation on the lots, homeowners could decide not to keep this vegetation. Homeowners could even plant invasive exotics which escape and invade nearby forests. Developments that have conserved forest fragments and have conserved trees/native vegetation in built areas should have funds allocated to manage these areas. In particular, a neighborhood educational program should be implemented that helps to raise awareness among residents about conservation. Management and education would reduce/minimize impacts stemming from built areas, such as invasive species spreading into natural areas. In particular, we recommend the following:

- Educational Signage Program: Because many impacts originate from nearby residential and individual homeowner decisions, we suggest raising awareness about these impacts. We also recommend actions that would retain the biological integrity of the forest fragments and even enhance the habitat values of yards and neighborhoods. Installing neighborhood educational kiosks with environmental panels is one way to raise awareness. This type of education program can impact homeowner knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors (Hostetler et al. 2008). See neighborhood signage example at http://www.thenatureofcities.com/2015/06/14/how-can-we-engage-residents-to-conserve-urban-biodiversity-talk-to-them/, and https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/uw407.

- Management Plan and Funding: A management plan should address how the built and conserved areas will be managed to protect biodiversity. Consider the creation of a funding source to help with the management of natural areas. Funds can be collected from homeowner association dues, home sales (even resales), property taxes, and the sale of large, natural areas to land trusts with some of the funds retained for management.

- Codes, Covenants, and Restrictions (CCRs): Implementing CCRs that address environmental practices and long-term management of yards, homes, and neighborhoods can help towards long-term protection of trees in residential areas. These CCRs should describe environmental features installed on lots and shared spaces and appropriate measures to maintain these. An example of an environmental CCR can be found at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/uw248.

- Provide Snags for Cavity-nesting birds: Consider leaving dead and dying trees standing as "snags." Many bird species use snags for feeding and nesting. While nest boxes supply homes for many species, some woodpeckers will only use cavities they excavated themselves; thus, the need for snags. Also, many of the insects that occur in snags are food for woodpeckers and other bird species. If safety is a concern in leaving snags standing, ask a tree surgeon to cut the snag to about 15 feet tall. This snag will still be valuable to wildlife.

For a species list that gives species identification, life history, results from three systematic reviews of the literature, and expected occurrence for 219 forest bird species recorded in studies conducted throughout the United States and Canada go to https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1WGlFiMlrhCd6fpTDoBSyAvKepXQAiMhzGb4CBSaeC3s/edit#gid=204625953. The Breeding Review columns show which species will breed in late or early successional forest fragments as well as which species are Interior-Forest Specialists (birds that do not breed in forest fragments). The Stopover Review column lists which species were observed in small forest fragments by studies conducted during the spring and fall migration seasons. The Built Environment Review columns show which species were observed within residential areas and gives the season of the observation. The Synanthropic Review columns show which species are synanthropic (urban-adapted species commonly found within the built matrix). Species are listed alphabetically by Order, Locality, and Common Name.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Renewable Resources Extension Act, UF/IFAS project 1000606.

Literature Cited

Hostetler, M., Swiman, E., Prizzia, A., and Noiseux, K. 2008. "Reaching residents of green communities: Evaluation of a unique environmental education program." Appl. Environ. Edu. Commun. 7, 114–124.

In this development scenario, some large and small amounts of tree canopy were conserved in the planned residential area. The total amount of forest conserved is 100 acres (80 acres occupied by sixteen 5-acre canopy patches, one 15-acre canopy patch, and 5 acres occupied by five 1-acre canopy patches).