The Noble Trumpeter

Credit: Dennis Church (left) and Sheri Nadelman (right), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/legalcode

- Breeding = Winter, Spring, Summer —

- Habitat = Wetland, Grassland

- Status = Federal Not Listed, State Listed Threatened

Scientific Name: Antigone canadensis pratensis

Common name: Florida sandhill crane

Habitat: Freshwater marshes, prairies, open pine forests, pastures, urban and suburban areas

Physical Description:Primarily graybirds with long necks and long legs, a bald spot of red skin on top of the head, and a white cheek patch (Figure 1).Cranes fly with their neck and legs outstretched. Males and females look similar, and adults can be almost 4 feet tall with a wingspan over 6 feet.

Reproductive Rate: 1 to 3 eggs with an average of 2, incubation 29–32 days. The young (typically 1–2) fledge at 65–70 days and are fully independent around 248–321 days.

Lifespan: Average of 7 years (but can be greater than 20 years)

Dispersal and Home Range: Average dispersal from birth site is 2.5 miles for males and 7.2 miles for females. Year-round home ranges for paired adults average 1100 acres and may overlap with other pairs, but exclusive nesting territories range from 300 to 635 acres.

Credit: Pixabay.com, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/legalcode

Credit: Art Nadelman, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/legalcode

Biology and Behavior: Florida sandhill cranes rely on shallow marshes for nesting and roosting and open upland and wetland habitats for foraging (with vegetation <20 inches high). They are omnivorous, feeding on seeds, young green shoots, grain, berries, insects, earthworms, crayfish, and small vertebrates. They scratch with their feet or probe with their bills to obtain food underground. Sandhill cranes are socially monogamous, and pair bonding begins at 2 years of age. The average age of first successful reproduction is 5 years. Courtship consists of an elaborate dance that features jumping, running, and wing flapping (Figure 2). The primary nesting season is February to April. They build nest platforms from emergent vegetation in shallow water averaging 5 to 13 inches deep (Figure 3). Pairs may re-nest up to 3 times in a year if a nest fails, typically in the same wetland. Within 24 hours of hatching, young cranes can travel from the nest with their parents but remain flightless for up to 70 days. Many chicks die before fledging, mostly from predation by raccoons, bobcats, bald eagles, river otters, red-tailed hawks, great-horned owls, feral hogs, coyotes, and alligators.

History: The range of the Florida sandhill crane diminished in the 20th century due to habitat degradation and hunting. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1916 protected all sandhill crane subspecies from hunting, but hunting seasons have been reopened in some states. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commissionlisted the Florida sandhill crane as a threatened species in 1974 due to habitat loss, and they remain legally protected from hunting in Florida.Between 1974 and 2003, potential crane habitat in Florida declined by 17%, and the population was estimated to have declined by 36%. However, more recent studies suggest the population is increasing, and productivity rates are associated with a stable and growing population, possibly because cranes are usingsuburban areas.

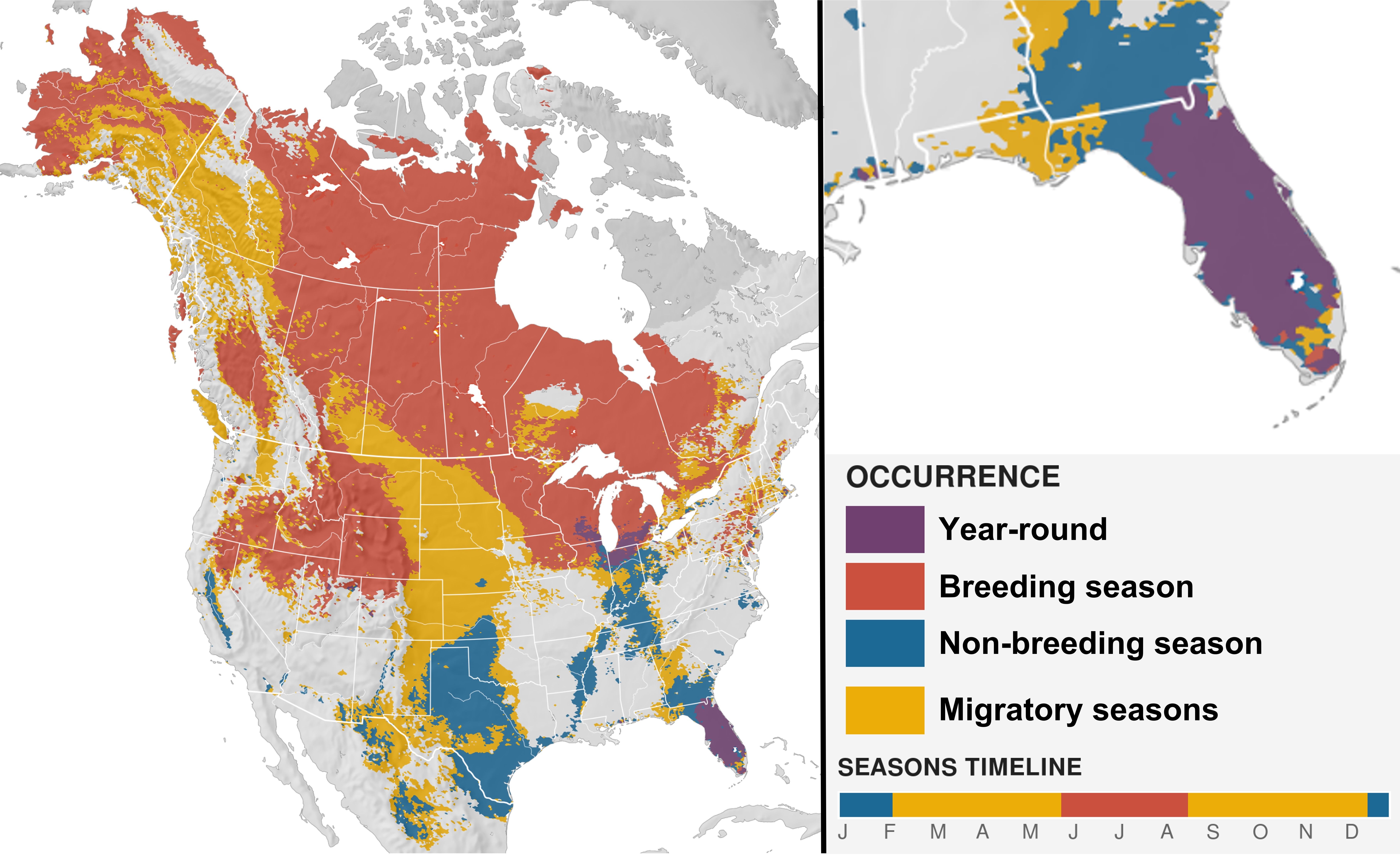

Distribution: The Florida sandhill crane is non-migratory and ranges from Georgia’s Okefenokee Swamp to the Everglades. Florida’s Kissimmee and Desoto Prairie regions have the largest populations. Another subspecies, the greater sandhill crane, winters in Florida, with as many as 25,000 cranes arriving in Florida in October–November and leaving for their northern breeding grounds from January–March (Figure 4). The two subspecies are often visually indistinguishable.

Credit: Birdsoftheworld.org, eBird data from 2005–2020. Estimated for 2019. Fink, D., T. Auer, A. Johnston, M. Strimas-Mackey, O. Robinson, S. Ligocki, W. Hochachka, C. Wood, I. Davies, M. Iliff, L. Seitz. 2020. eBird Status and Trends, Data Version: 2019; Released: 2020. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. https://doi.org/10.2173/ebirdst.2019

Threats: The primary threat facing the Florida sandhill crane is loss of habitat from wetland drainage, conversion of native rangeland for agricultural or urban development, and fire suppression allowing woody encroachment of herbaceous marshes. When upland habitat for foraging isn’t available near nesting sites in wetlands, they may travel from the nest territory to find food, making them more vulnerable to predators, vehicles, and collisions with powerlines. Flooding can lead to nest failure, and runoff from developed areas can increase the impact of floods. Climate change is likely to exacerbate the threat of habitat loss through changes in hydrology and fire regimes. Although cranes have adapted to living around humans, disturbance of nesting cranes by humans can lead to nest abandonment and failure (Figure 5). Adults with young are most likely to cross a road on foot. Free-ranging dogs and cats also pose a threat to cranes, especially eggs and young, which they may harass and kill. In addition, cranes are at risk from chemicals, for example, cranes feeding on harvested peanut fields can be partially paralyzed and may die from mycotoxins from rotting peanuts.

Credit: FWC Research Institute, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/legalcode

Did you know?

The earliest known fossil of a sandhill crane, estimated at 2.5 million years old, was found in Florida.

Fast Facts

- The crane’s distinctive loud call, described as trumpeting, rattling, bugling, or croaking, can be heard up to 2 miles away.

- Although Florida sandhill cranes are omnivorous, they do not “fish” like herons by stabbing their prey.

How You Can Help

- Don’t feed cranes; it disrupts their natural diet and is illegal in Florida.

- Keep your distance (~100 yards) from nesting cranes to prevent nest abandonment.

- Slow down and watch for cranes crossing the road when you are driving, especially during breeding season.

- Keep cats and dogs inside or on a leash to avoid disturbance and predation.

- Hang bird feeders high so cranes cannot directly forage from them.