What is highly pathogenic avian influenza?

Avian influenza is a highly contagious respiratory virus that circulates globally among wild birds, particularly waterfowl and shorebirds, often with no clinical signs. The virus can move from country to country and continent to continent when infected birds migrate long distances. Some strains of the virus have low pathogenicity, meaning the virus produces only mild disease in domesticated poultry that are exposed to the virus, like chickens and turkeys. However, some strains can cause severe disease and mass die-offs in poultry. Such strains are termed highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses. They can cause huge losses to commercial poultry farms, and also threaten backyard flocks, native wildlife, and human health. In January 2022, a new Eurasian strain of HPAI, belonging to what is called the H5N1 group of influenza viruses, was detected in wild birds in the eastern United States for the first time. The following is intended as a summary of the current outbreak of HPAI in the United States for the general public with guidelines for preventing infection in people and domestic animals.

What species are affected?

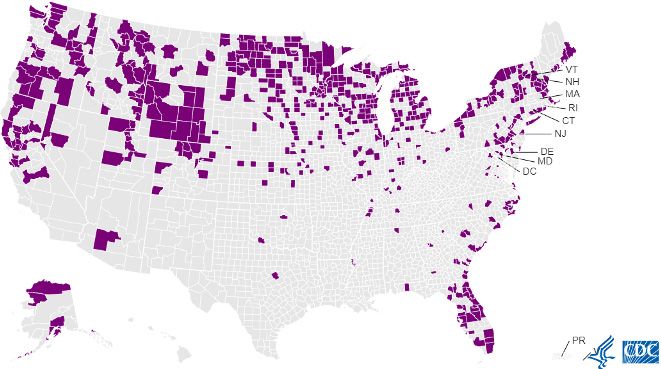

As of July 2022, this Eurasian H5N1 has spread quickly in the United States, killing wild birds in more than 40 states (Figure 1) and impacting more than 60 species encompassing waterfowl, shorebirds, seabirds, raptors, vultures, and more. The virus has caused the first recorded HPAI outbreak in Florida, predominantly among bald eagles and black vultures. Some mammals are also susceptible to HPAI, for example when exposed to infected birds or carcasses. In fact, red fox kits have developed signs of disease and died during the current outbreak, and a bottlenose dolphin in Florida was found dead and infected with the currently circulating strain of HPAI.

Credit: CDC

Since February 2022 when the first commercial poultry farms were impacted, more than 40 million domestic poultry have died or been euthanized, marking the first notable outbreak of HPAI since 2014–2015 when a different strain affected over 50 million birds. While lethal to many birds and some mammal species, the current circulating strain is not particularly infectious in humans. As of June 2022, only two people have tested positive for H5N1 worldwide, one of whom was a worker at a poultry processing plant in the United States. Nonetheless, the CDC has developed a potential vaccine against the current HPAI strain as part of an ongoing process to prepare for pandemic threats.

Because the virus is primarily affecting animals, the outbreak is called an epizootic. Although lessons learned from the HPAI outbreak in 2014–2015 have helped to limit the impact of the current outbreak in commercial poultry, numbers of wild birds impacted have far exceeded the number affected in 2014–2015. In multiple instances, 1000 or more individuals of one species have died in a single mortality event. Particularly vulnerable species are those with low reproductive rates or small, endangered populations.

Who has to worry?

The currently circulating HPAI strain is a low risk for human infection, but it is still recommended that people avoid contact with wild birds. Some situations will exist where people may be in close contact with wild birds, such as with hunting or the use of backyard bird feeders and baths. While H5N1 has been detected in a number of game birds during the current outbreak, the virus has been detected in very few birds that are commonly found at backyard feeders or baths, but basic precautions are still warranted in all of these scenarios. Since the virus is spread through feces and respiratory secretions from the nose, mouth, and eyes, basic precautions are to:

- Avoid contact with bird droppings and birds that are sick or found dead;

- Wear disposable gloves and refrain from smoking, eating, or drinking when cleaning game;

- Wash hands with soap and water or alcohol-based hand sanitizer immediately after handling game, bird feeders, or bird baths;

- Wash any potentially contaminated tools or surfaces with soap and water, then disinfect with a fresh bleach solution (1/3 cup bleach in 1 gallon of water) for at least 10 minutes;

- When disposing of a dead bird, offal, or feathers, use an inverted bag or disposable gloves to place potentially contaminated material into a plastic double bag, then throw the bag away in a garbage can that is secure from children, pets, and wild animals.

People who come into contact with wild birds should monitor themselves for 10 days for symptoms, like fever, cough, runny nose, sore throat, headache, muscle aches, shortness of breath, or diarrhea. People who develop symptoms should contact their physician or local public health office for potential H5N1 testing.

For those with pet birds or backyard flocks, particularly those consisting of chickens, turkeys, ducks, geese, quail, pheasants, or guinea fowl, assessment of biosecurity practices is strongly advised. Recommended biosecurity practices to keep your pet bird or backyard flock healthy include:

- Minimizing contact with visitors and other pets, especially those in contact with other birds (domestic or wild) or those who frequent natural waterbodies;

- Washing hands with soap and water before and after handling birds and related equipment;

- Using dedicated and routinely cleaned and disinfected clothes, shoes, and equipment;

- Avoiding contact with wild birds by covering or enclosing outdoor areas, securing food bins, cleaning up wasted or spilled feed, and minimizing standing water on the property;

- Limiting travel to shows, sales, and swaps; separating new or returning birds for 30 days.

If a pet or backyard bird suddenly dies or develops signs consistent with HPAI, contact your local veterinarian, agricultural Extension office, animal health diagnostic laboratory, or state veterinarian. Signs consistent with HPAI in birds include respiratory (nasal discharge, gasping for air, coughing, or sneezing), nervous system (tremors, paralysis, twisted neck, or lack of coordination), gastrointestinal (diarrhea), and general signs, like lack of energy and purple discoloration or swelling of body parts.

Informative weblinks:

CDC. 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/avianflu/hpai/hpai-background-clinical-illness.htm

CDC. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/avianflu/avian-flu-summary.htm

CDC. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/avianflu/index.htm

CWHL. 2022. https://cwhl.vet.cornell.edu/article/highly-pathogenic-avian-influenza-update-6922

FWC. 2022. https://myfwc.com/research/wildlife/health/avian/influenza/faq/

USGS. 2022. https://www.usgs.gov/centers/nwhc/science/avian-influenza-surveillance

USDA. 2022. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalhealth/animal-disease-information/avian/avian-influenza/ai