What is chronic wasting disease?

This article is intended to summarize for the general public what is currently known about chronic wasting disease (CWD) and its impacts, with information about practices to minimize spread of the disease. Chronic wasting disease is a prion disease that affects hoofed animals, particularly cervids, notably deer, including white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), elk (Cervus canadensis), caribou (Rangifer tarandus), and moose (Alces alces). Prion diseases are also called transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), a family of rare progressive neurodegenerative disorders that affect both people and animals; for example, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) in people, CWD in cervids, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in cattle, and scrapie in sheep. Some evidence suggests that prion diseases can be passed from animals to people, as with “mad cow disease,” in which people develop variant CJD after eating meat from cattle affected by BSE. However, at this time, CWD is only known to affect animals, as there is currently no conclusive evidence of a person developing CJD or variant CJD after consuming meat from a CWD-positive animal.

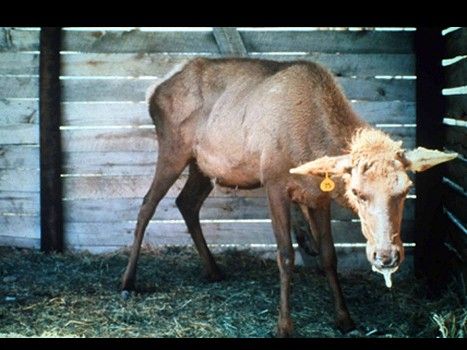

Prions are disease-causing agents that can be transmitted, leading to abnormal folding and clumping of proteins that are most abundant in the brain. An accumulation of these abnormal proteins leads to brain damage and characteristic signs (Figure 1).

Credit: Wyoming Game and Fish Department and CWD Alliance

Clinical Signs

Weight loss (“wasting”)

Poor body and coat condition

Excessive salivation (drooling)

Excessive urination

Excessive drinking

Splayed leg posture

Lowered ears and/or head Somnolence (drowsiness)

Ataxia (poor muscle control or clumsiness)

Head tremors

Behavioral Signs

Decreased social interaction

Decreased awareness of surroundings

Loss of fear of humans

Pacing

Like other prion diseases, CWD is believed to develop slowly, with characteristic signs of the disease appearing over a year after initial infection but then rapidly progressing. It is always fatal. There is no cure or treatment for CWD. Diagnosis of CWD requires analysis of samples from the animal’s brain, spinal cord, and lymph nodes, and therefore a diagnosis cannot be made in a live animal, but only post-mortem. Current research is investigating live animal tests for diagnosing and detecting CWD before death using samples of lymph tissue from the tonsils or rectum, from feces, or from nasal brush samples (Haley and Hoover 2015).

Where is CWD found?

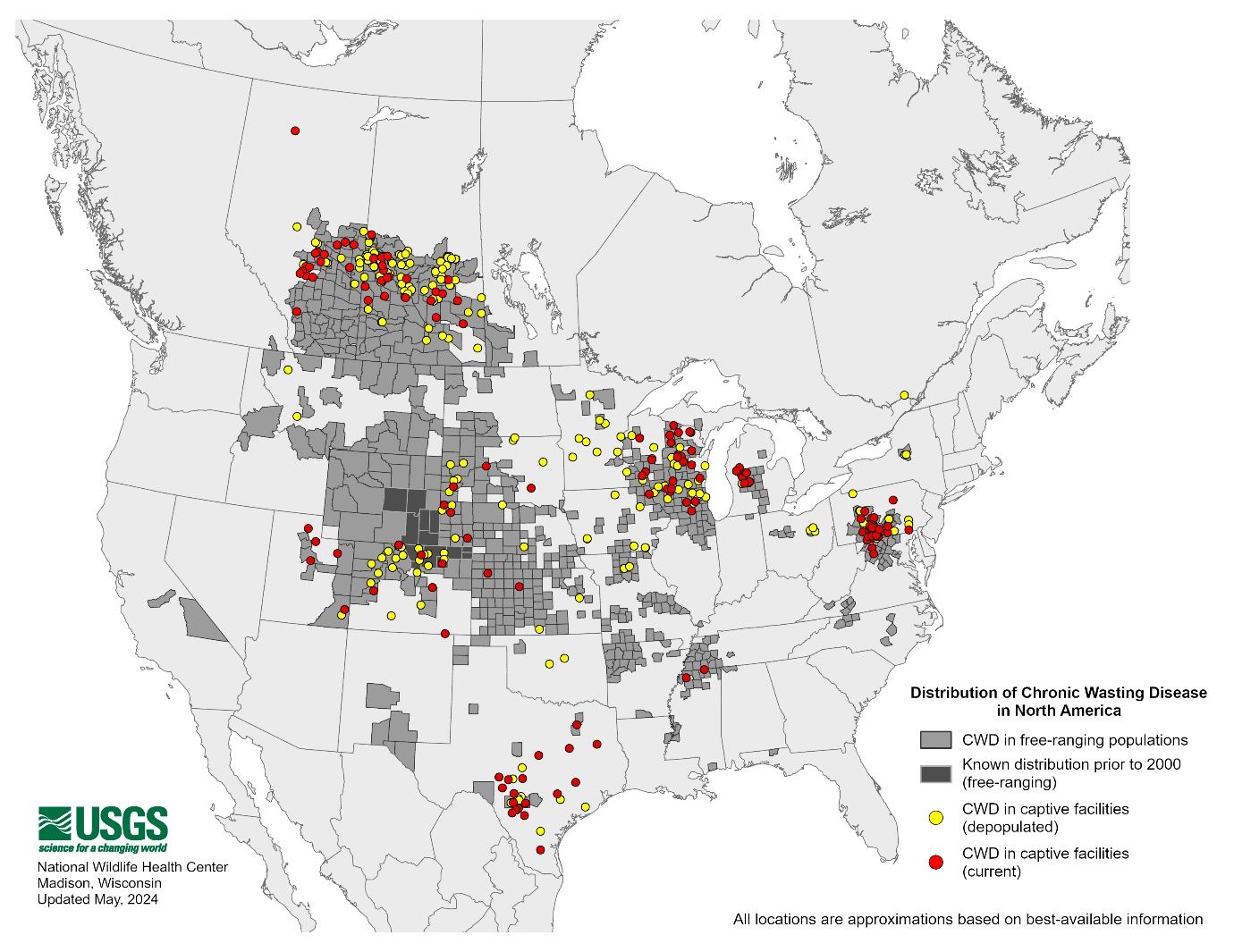

Chronic wasting disease was first identified in captive mule deer in a research facility in Colorado in the late 1960s and in free-ranging cervids in the 1980s. Since then, the disease has spread to 34 states in the United States (Figure 2), five Canadian provinces, and four other countries (Norway, Finland, Sweden, and South Korea). Established areas are regions where CWD has persisted for an extended period of time, with the area eventually expanding as infection spreads outwards. Chronic wasting disease infection rates in free-ranging deer and elk in established areas range from 10% to 25%, whereas infection rates up to 79% have been reported for captive deer populations in established areas. The first known case of CWD in Florida was reported in June 2023. Officials from Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) reported that a single, 4.5-year-old white-tailed deer tested positive for CWD in Holmes County during routine surveillance activities. The animal was road-killed and looked otherwise healthy.

Credit: U.S. Geological Survey (USGS)

How is CWD transmitted and spread?

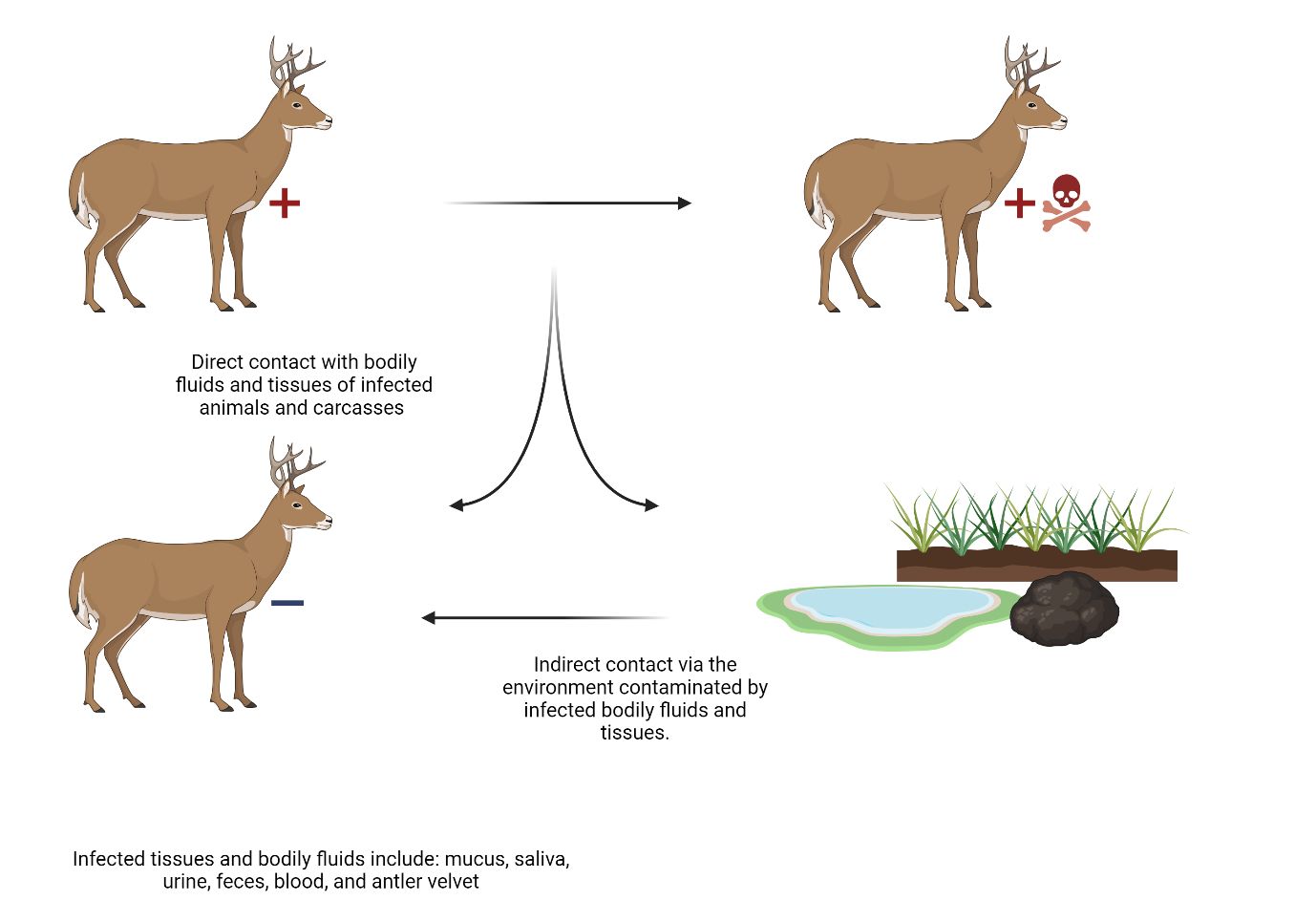

Chronic wasting disease is transmitted either directly through contact with body fluids, such as feces, saliva, blood, antler velvet, or urine, of living or deceased affected animals; or indirectly through contact with contaminated soil, food, or water (Figure 3). Chronic wasting disease remains in the environment for a long time once it is established. In fact, CWD prions can remain infective in soil for at least two years. Ticks may play a role in CWD transmission by ingesting and excreting transmission-relevant amounts of the prion (Inzalaco et al. 2023). Additionally, prions can be absorbed by plant roots, sequestered in plant material, and transmitted to animals that eat them, suggesting that livestock forage or crop transportation may also facilitate the movement of CWD (Carlson et al. 2023).

The spread of CWD can occur through the movement of infected animals or cervid parts between farms (Joly et al. 2003; Mori et al. 2024) or from direct or indirect contact of farmed cervids with free-ranging cervids. Chronic wasting disease can spread rapidly among individuals on cervid farms due to the larger numbers of deer in close proximity (Bartelt-Hunt and Bartz 2013; Zabel and Ortega 2017). In fact, CWD has infected up to 100% of cervids in captive herds, in some instances with an infection rate twenty times higher than that for free-ranging cervids (Mori et al. 2024). Hunters transporting CWD-infected carcasses can also facilitate the spread of the CWD prion over long distances, while scavenging of carcasses by other wildlife may also contribute to geographic expansion of CWD. In a study on decomposition, a deer carcass persisted for 18–101 days and was visited by multiple species including deer, raccoons, coyotes, opossums, vultures, and crows, which may spread the disease by carrying CWD-affected tissue away from the carcass site (Saunders et al. 2012).

Credit: BioRender. Wisely, S. (2025)

What are the concerns?

Chronic wasting disease raises both economic and wildlife management/conservation concerns. A study conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) found that federal government agencies spent around $284.1 million between 2000 and 2021 on efforts including research, surveillance, education, outreach, depopulation, and agency operation related to CWD, while state government agencies collectively spent $28.4 million on CWD prevention and response in 2020 alone, with an average cost of more than $500,000 per state.

The sale of hunting permits generates millions of dollars in revenue at the state level for wildlife management and supports tens of thousands of jobs. For example, FWC uses the profits from the sale of deer hunting permits to specifically support deer and habitat management throughout Florida, including CWD surveillance. It has been reported that natural resources agencies in states with known CWD cases spend more than eight times the amount spent by agencies in states with no known cases, limiting financial resources in the affected states that could otherwise be used for management of the deer population as a whole and for other species. At the same time, hunter participation has declined over time, especially when CWD is detected in a region, resulting in an economic impact in the tens of millions of dollars, with rural areas most impacted. There is also a concern that establishment and expansion of CWD in Florida could further endanger Key deer (Odocoileus virginianus clavium). The Key deer is the smallest subspecies of white-tailed deer and is only found in the Florida Keys.

Economic impact data for the captive cervid industry is lacking, but in states where CWD was present, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) found an average 54% reduction in captive cervid numbers, representing an estimated loss of >$230 million (Mori et al. 2024). The industry not only loses money due to reduced cervid numbers but also incurs additional expenses related to sample collection and testing and regulations that require quarantine, movement restrictions, infrastructure improvements (e.g., double fencing), and/or depopulation. In response to a costly outbreak of epizootic hemorrhagic disease (EHD) in Florida’s captive deer population in 2012, the University of Florida created the Cervidae Health Research Initiative (CHeRI), which supports research, education, and assistance for industry challenges related to captive cervid health and production, including CWD.

What action can be taken?

- It is strongly recommended to test cervids before consuming meat, particularly in areas where CWD is known to be present. There is currently no conclusive evidence of a person developing Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) or variant CJD after consuming meat from a CWD-positive animal, but the symptoms and outcomes for people infected with other prion diseases are severe, and thus caution is warranted.

- Do not eat meat or other tissues from a CWD-positive animal. Again, caution is warranted due to the severity of symptoms and outcomes for people infected with other prion diseases.

- Know the CWD status and regulations where you hunt. Follow all state laws regarding the transportation of meat or carcasses.

- Do not use animal feed or other attractants for purposes of hunting or observation. This practice brings cervids into close proximity with one another and facilitates spread of the CWD prion.

- Do not shoot, handle, or eat meat from cervids that look sick or behave strangely. Do not handle or eat the meat of cervids that are found dead (e.g., from unknown cause, road-killed, or killed by predators).

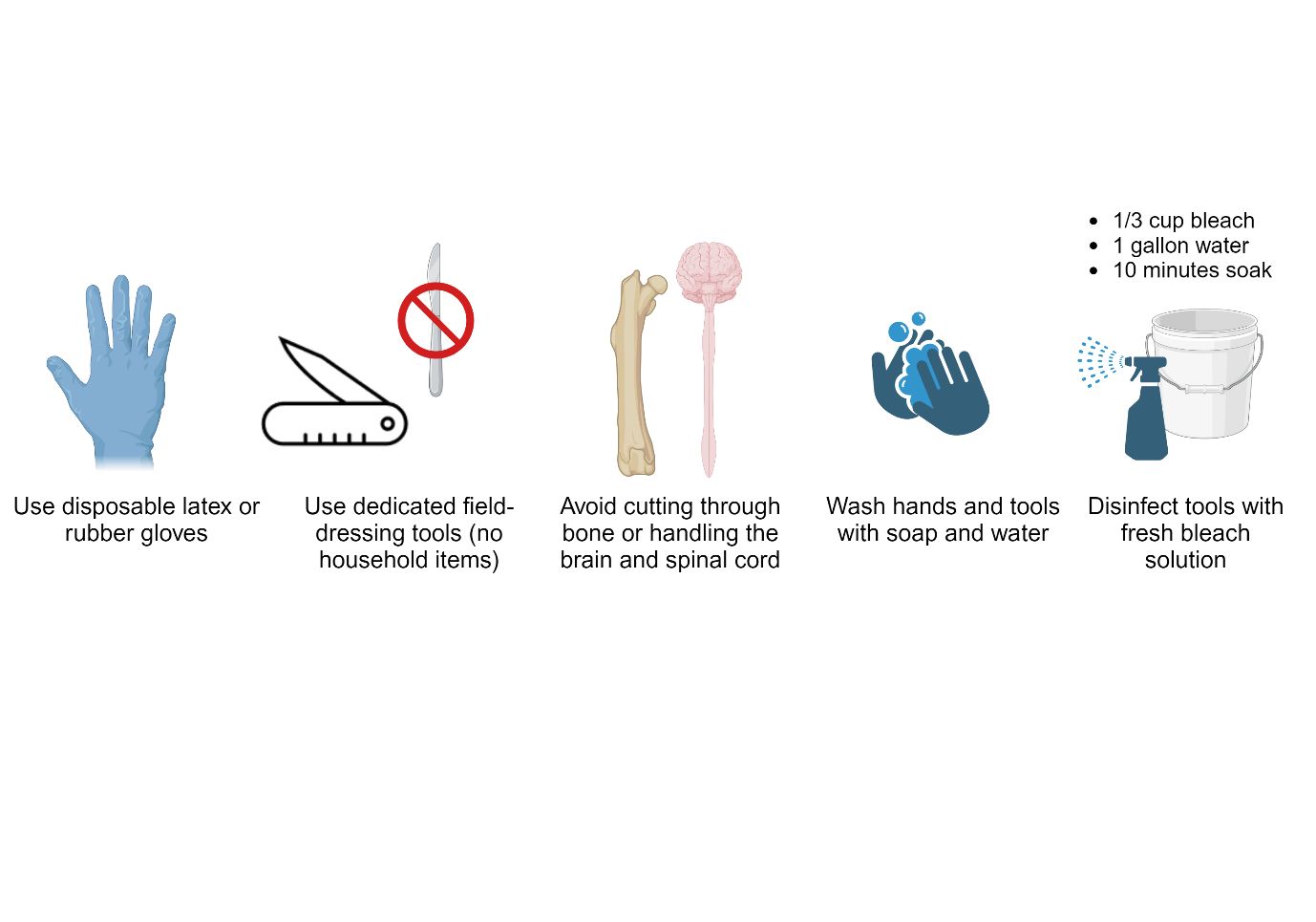

- Follow recommended field-dressing procedures for cervids (Figure 4).

- When you have an animal commercially processed, ask that your animal be processed individually to minimize mixing meat from other animals.

For farmed cervid owners, to minimize the potential economic impact of CWD and maintain strong trade in cervids and their products, buy animals from a trusted source and participate in the USDA’s CWD Voluntary Herd Certification Program (see: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/cervid/chronic-wasting/herd-certification) which combines biosecurity and surveillance practices to reduce CWD risk.

If a deer has symptoms that are consistent with CWD or if hunters wish to voluntarily submit deer heads for testing in Florida (skull caps and antlers can be removed and kept, as long as all flesh is removed), contact FWC via the CWD hotline: 866-CWD-WATCH (866-293-9282). For the latest information on FWC’s CWD Monitoring Program, see: https://myfwc.com/research/wildlife/health/white-tail-deer/cwd/monitoring/.

Credit: BioRender. Wisely, S. (2025

Additional Informative Weblinks

CDC. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/prions/index.html

CDC. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/chronic-wasting/animals/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/prions/cwd/index.html

USGS. 2019. https://www.usgs.gov/centers/nwhc/science/chronic-wasting-disease

References

Angers, R. C., T. S. Sewar, N. Napie, M. Green, E. Hoover, T. Spraker, K. O'Rouke, et al. 2009. “Chronic Wasting Disease Prions in Elk Antler Velvet.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 15 (5): 696–703. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1505.081458

Bartelt-Hunt, S., and J. C. Bartz. 2013. “Behavior of Prions in the Environment: Implications for Prion Biology.” PLoS Pathogens 9 (2): e1003113. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003113

Carlson, C. M., S. Thomas, M. W. Keating, P. Soto, N. M. Gibbs, H. Chang, J. K.Wiepz, A. G. Austin, J. R. Schneider, R. Morales, and C. J. Johnson. 2023. "Plants as Vectors for Environmental Prion Transmission.” Iscience 26 (12): 108428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.108428

Chiavacci, S. J. 2022. “The Economic Costs of Chronic Wasting Disease in the United States.” PLoS One 17 (12): e0278366. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278366

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. “Economics.” Accessed May 2, 2024. https://myfwc.com/about/overview/economics/

Haley, N. J., and E. A. Hoover. 2015. “Chronic Wasting Disease of Cervids: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives.” Annual Review of Animal Biosciences 3:305–325. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-animal-022114-111001

Inzalaco, H. N., F. Bravo-Risi, R. Morales, D. P. Walsh, J. A. Pedersen, W. C. Turner, and S. S. Lichtenberg. 2023. “Ticks harbor and excrete chronic wasting disease prions.” Scientific Reports 13:7838. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34308-3

Joly, D. O., C. A. Ribic, J. A. Langenberg, K. Beheler, C. A. Batha, B. J. Dhuey, R. E. Rolley, et al. 2003. “Chronic Wasting Disease in Free-Ranging Wisconsin White-Tailed Deer.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 9 (5): 599–601. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid0905.020721

Mori, J., N. Rivera, J. Novakofski, and N. Mateus-Pinilla. 2024. “A Review of Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) Spread, Surveillance, and Control in the United States Captive Cervid Industry.” Prion 18 (1): 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/19336896.2024.2343220

National Agricultural Statistics Service. 2022. 2022 Census Volume 1, Chapter 1: State Level Data. United States Department of Agriculture. Accessed May 2, 2024. https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2022/Full_Report/Volume_1,_Chapter_1_State_Level/Florida/

Rivera, N. A., A. L. Brandt, J. E. Novakofski, and N. E. Mateus-Pinilla. 2019. “Chronic Wasting Disease in Cervids: Prevalence, Impact and Management Strategies.” Veterinary Medicine: Research and Reports pp. 123–139. https://doi.org/10.2147/VMRR.S197404

Saunders, S. E., S. L. Bartelt-Hunt, and J. C. Bartz. 2012. “Occurrence, Transmission, and Zoonotic Potential of Chronic Wasting Disease.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 18 (3): 369–376. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1803.110685

Zabel, M., and A. Ortega. 2017. “The Ecology of Prions.” Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 81 (3): e00001–17. https://doi.org/10.1128/MMBR.00001-17