Florida is home to a myriad of potential natural disasters. Florida horse owners are commonly prepared for hurricanes, but may be less ready for fires, flooding, and lightning, all of which pose significant danger to both people and horses. Creating personalized emergency plans for evacuating or sheltering-in-place with horses helps horse owners to be as prepared as possible when natural disasters occur.

Disaster-Specific Considerations

Different types of natural disasters pose unique threats to property and animals, so emergency plans need to be tailored to specific scenarios. Damage considerations and recommended plans for the most common types of natural disasters are detailed below.

Hurricanes: Potential wind damage to property; flooding; increase in mosquito populations and insect-borne disease transmission; flying debris-related damage and injury; loss of electricity; electrocution risks from downed power lines; lack of access to clean water; substantial displacement of animals. Both evacuation and shelter-in-place plans are recommended.

Fire: Risk of injuries from direct burns, extreme heat, smoke inhalation, and barn collapse. Can also cause property damage and animal displacement. Evacuation routes may be impacted and may involve very little lead time. Fires may originate from surrounding forest fires or on-site barn or property fires. Evacuation plan is recommended.

Flood/Mud: Horses trapped in flooded areas or mud may require skilled technical rescue by first responder professionals. Increase in mosquito populations and both insect-borne and waterborne disease transmission. Affected animals may suffer from hypothermia, starvation, and injury-related disease. Evacuation plan is recommended.

Tornadoes: Potential property damage, electrocution injury from downed power lines, lightning strikes, secondary flood and/or fires, and fear-induced animal accidents. Both shelter-in-place and evacuation plans are recommended.

Making Your Plan

Finding an evacuation destination may sound daunting. County- and state-sponsored shelters as well as privately owned shelter facilities are often organized by local animal officials and advertised on state and local websites and social media. UF/IFAS Extension agents are also a good source of local evacuation center information. Contact and visit any prospective shelter ahead of time to understand their policies, services, and capacity limitations.

Each sheltering location has its own set of rules, and most facilities will require that you care for your own animals while there. Many equine shelters do not have facilities for housing people. Options for local lodging are an important part of a disaster preparedness plan.

Plan to travel with all necessary items to fully maintain your animals for several days. Shelters often do not have enough supplies for every animal during emergencies. This may include buckets, bedding material, hay nets, feed and water, a clean garbage can to be filled with potable water, a first-aid kit, several halters and lead ropes, a muck fork, fly spray, and grooming supplies.

Water and Feed

Obtain a 3- to 7-day supply of feed, water, and medications for all animals on the property. Move hay and feed off the floor to reduce water damage. When possible, keep items in watertight bins to protect them from the elements and allow quick transport if evacuation is necessary (Figure 1). Plan for at least 10–12 gallons of clean water per horse per day. Water can be stored in rain barrels or trash cans with plastic liners. Wells are susceptible to contamination by bacteria and dead animals after flooding and should be used with caution after natural disasters.

Credit: E. Norstrem

Documentation

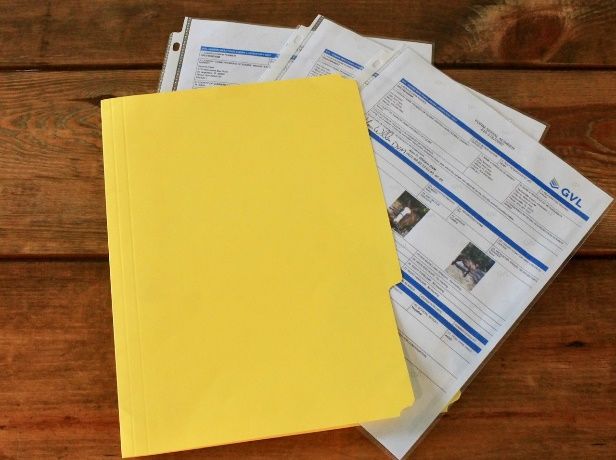

For both evacuation and shelter-in-place plans, maintaining good digital and/or paper records is crucial for mitigating hardship and expediting recovery after a disaster. Laminate paper copies and backups, or store in watertight containers or sealable bags (Figure 2). Key documents that should be up to date, readily available, and printed with digital backup copies include:

- Vaccination records, including those for Coggins and rabies

- Permanent identification and any registration records

- Key medication prescriptions or health histories

- Health Certificate

- Photos for identification, including those showing you with your animals

Credit: E. Norstrem

Fence and Pasture Preparations

If sheltering in place, take steps to make the property as safe as possible. Avoid sheltering horses in pastures with barbed wire fencing, as the wire can become submerged and cause serious bodily injury to both animals and humans trying to move around the property. Fencing should be secure and visible to prevent injury from horses charging fence lines. Do not solely rely on electric fencing, which becomes ineffective with power outages or damage from fallen trees.

Animal Identification

Identifying horses using temporary and/or permanent marking improves the chances they will be returned to their owners if they are lost or displaced during a natural disaster.

Methods of permanent identification include microchips, hot iron or freeze brands, and lip tattoos. There are pros and cons to each type of identification. Brands and tattoos can fade over time and must be reported on Health Certificates and EIA (Coggins) certificates. Microchips are small transponders (about the size of a grain of rice) that each contain a unique ID code linked to owner contact information. They are quickly becoming one of the most common methods for permanent animal identification. Microchipping can be invaluable for large-scale post-disaster animal recovery efforts, which may involve hundreds or even thousands of displaced animals. Because each microchip is linked to owner contact information, it is essential that animal owners frequently check and update their contact information in the microchip’s online database.

A guide for microchipping can be found at https://www.aspcapro.org/sites/default/files/aspca_equine_chip.pub_.pdf.

Temporary identification methods are useful for quick and easy delivery of key information, such as owner/farm name and address, primary and secondary phone numbers, and the animal’s existing health conditions. Examples of temporary identification methods include:

- Luggage or dog tags braided into the mane and/or tail (Figure 3)

- Velcro reflective neck collars or leg bands

- Shaving phone numbers into the coat using pet clippers

- Marking the body with name and phone numbers using water-resistant livestock chalk, lipstick, or spray paint—vibrant colors are best (Figure 4)

Credit: E. Norstrem

Credit: E. Norstrem

Note: Anything attached to the head or neck of the horse should be attached with a breakaway halter/collar or Velcro attachment to prevent injury.

Vaccinations

Keeping horses up to date on preventative healthcare measures such as vaccination will ensure they are healthy and fit for travel should a natural disaster arise. Core vaccines designated by the American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) (i.e., vaccinations against tetanus, West Nile virus, eastern/western equine encephalitis, rabies) will prevent horses from contracting these often-fatal diseases during or after a natural disaster, when extensive flooding, increased mosquito populations, and displaced wildlife can put horses at higher risk of infection. Horse owners should also maintain current EIA certificates (Coggins) on all horses on the property. Although a veterinary health certificate requirement may be waived to evacuate horses across state lines during a natural disaster, it is best to have a plan to get one from your veterinarian in the event that the certificate is needed.

- More information on equine vaccinations can be found on the Equine Disease Communication Center website.

- More information on movement requirements for horses traveling within and outside the state of Florida can be found on the FDACS website.

Insurance

Insurance is an additional security measure to protect against unexpected costs of medical care, loss of use, death, or liability to property and people. Coverage varies by company and policy, and may include medical treatment, emergency surgeries, euthanasia, lawsuit protection, and property damages. As with any insurance plan, horse owners should consider the cost versus benefit and carefully review policy terms to understand any limitations or exclusions.

What to Expect at Agricultural Inspection Station Stops

All trucks with trailers, regardless of whether they are loaded with animals or not, should stop at agricultural inspection stations. Empty trailers are generally quickly waved on. At the inspection station, have your documents well organized and ready. Coggins should be easy to read and up to date. Blurry or faded photocopies or documents will delay the process. If you have multiple Coggins, keep them well organized by year and/or animal. If you are crossing state lines, you will also be asked to provide a current Health Certificate. During emergencies, this requirement may be lifted. At the agricultural inspection station, the officer will review your paperwork and confirm the animals through a visual inspection. Officers may need to open windows to confirm animal identities. Let the officer know if there are any health, behavior, or other issues before they attempt to inspect the animals.

Biosecurity

Take steps to keep horses as calm, clean, and dry as possible during and after natural disasters. Stress and poor hygiene increase susceptibility to disease. Flood waters are often highly contaminated with bacteria and can cause significant skin disease in horses standing in water for prolonged periods. If your horse is showing signs of sickness at any time during or after evacuation, alert your shelter and veterinarian, and be aware that quarantine protocols may be needed to keep other horses safe. Never share water or feed with unfamiliar horses and avoid sharing equipment if possible. Keep horses in individual stalls or in paddocks with only their home herd mates whenever possible. Common courtesy is to avoid interaction with other people’s animals, even if permission is given, to minimize disease transmission. Horses should be monitored for signs of illness (inappetence, nasal discharge, coughing, diarrhea) or fever (greater than 101°F; take temperature twice daily) during sheltering and 14 days after they return home.

Emergency situations will undoubtedly be stressful for both people and animals, and care should be taken to minimize this stress whenever possible. Quiet housing with familiar horses will help calm some horses, while others may benefit from human interaction such as grooming. Signs of excessive stress may include loss of appetite, aggressive behavior, diarrhea, and stereotypies (weaving, pacing, cribbing).

Animal Technical Rescue (ATR) during or after a Natural Disaster

During natural disasters, horses may trap themselves in dangerous situations, such as falling into septic tanks, getting stuck in mud or flood waters, falling into sinkholes, or venturing into high areas like the lofts of barns. In these cases, trained professionals should be called to retrieve the horse using tools and techniques designed to maintain safety for the animals and people involved in the rescue efforts. The Florida State Agricultural Response Team (SART) and its affiliated partner, the University of Florida Veterinary Emergency Treatment Service (UF VETS) Animal Technical Rescue (ATR) Team, assists counties with skilled training in low- and high-angle ATR emergencies ranging from confined spaces, holes, gorges, mud, water, overturned trailers, etc.

UF VETS ATR is available as a support resource for local law enforcement and fire departments and must be requested by the local authority having jurisdiction and/or veterinarian on scene. The ATR Team will respond in the assistance of local fire or law enforcement but cannot respond independently to calls directly from the public.

While the UF VETS ATR Team only operates within a two-hour radius of Gainesville, members specialize in training county ATR teams across Florida to respond to ATR emergencies directly in their local area. These teams, equipped with the skills taught by UF VETS, stand ready to assist in ATR emergencies across the state of Florida (Figure 5).

Regardless of location, owners with an animal in a technical rescue emergency or who are witnesses to an emergency should contact their local 911 for assistance and alert their veterinarian.

To learn more about the UF VETS ATR Team and ATR training opportunities, visit www.ufvets.com.

Credit: UF VETS

Recovery of Animals after a Natural Disaster

As soon as possible after a natural disaster, try to find and examine all animals on the property. Use caution; horses may exhibit fractious behavior from stress or injury. Horse owners are advised to be trained in basic equine first aid. First responders and veterinarians often experience high call volumes after natural disasters, making on-farm medical assistance delayed or impossible.

Check fences and property for damage, debris, or safety issues. Call the power company if any power lines or towers are damaged. Take photos and record any damages to property, vehicles, barns, or animals. Dump any contaminated standing water and follow up with mosquito control protocols. File any needed insurance claims and contact your local SART representative, Emergency Operations Center, or UF/IFAS Extension agent if you have additional recovery needs.

Additional Disaster Preparedness Resources

- Florida State Agricultural Response Team (SART): www.FLSART.org

- Disaster Preparedness for Horses, FDACS

- https://responseteam.vetmed.ufl.edu/about/educational-resources/

- EDEN Equine Hurricane Preparedness Video

Sheltering In Place: Do’s and Don’ts

Do:

- Check all fence lines for structural integrity and any safety risks.

- Obtain a 3- to 7-day supply of feed, water, and medications for all animals on the property. Move hay and feed off the floor to reduce water damage.

- Leaving horses outside during disasters is generally recommended, unless the barn or shelter structures were built to withstand hurricane-force winds.

- Remove all halters or replace them with breakaway halters to prevent horses from getting their heads caught on structures or debris.

- Prepare an emergency barn kit that includes chainsaw and fuel, hammer, flashlight with extra batteries, wire cutters, nails, screws, and fencing materials.

- Maintain a well-stocked first-aid kit that includes a thermometer, stethoscope, and duct tape, as well as materials to clean and bandage a wound, wrap a limb, and remove a horseshoe.

- Make sure tractors and trucks are topped off with fuel and safe for use in case of emergency evacuation.

- Remove any free or unnecessary items from the barn to reduce flying-debris risk.

Don’t:

- Leave horses enclosed in poorly-constructed barns or in pastures with overhead power lines.

- Leave horses in low-lying areas prone to flooding.

- Tie or tether your horse to any structure.

- Park trailers and tractors under trees.

Evacuation: Do’s & Don’ts

Do:

- Have an evacuation plan BEFORE an emergency arises. Ideally, have 1–2 backup evacuation options.

- Maintain a list of regional evacuation center contacts.

- Perform a complete safety inspection on your truck and trailer, including tires, wiring, floors, and bearings.

- Ensure your horse is well-trained and comfortable getting in and out of trailers before an emergency situation. Emergency evacuation periods are not good times to train horses to load.

- Pack a 3- to 7-day supply of feed, water, and medications for all animals.

- Pack all emergency documentation, including EIA (Coggins) certificate, Veterinary Health Certificate, and vaccine history.

- Prepare an emergency kit that includes chainsaw and fuel, flashlight with extra batteries, hammer, nails, wire cutters, shovel, and rain gear.

- Maintain a well-stocked first-aid kit that includes a thermometer, stethoscope, and duct tape, as well as materials to clean and bandage a wound, wrap a limb, and remove a horse shoe.

- Be kind to others and work together to ensure the safety of both people and animals!

Don’t:

- Assume the shelter of your choice will have a space for you and show up without contacting them first.

- Assume there will be feed, water, or supplies at your final destination.