Key Points

- Encountering a horse health emergency is almost inevitable with horse ownership.

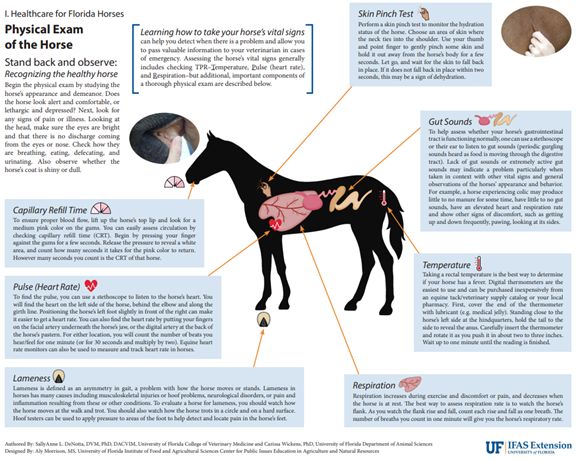

- Horse owners should practice physical examinations on their horse(s) and be familiar with normal equine vital signs (Figures 1 and 2). Being familiar with your horse’s normal physical exam parameters will enable you to easily and readily identify abnormalities.

- This publication aims to prepare horse owners to assess the severity of an injury or illness, provide general first aid, and know when to seek veterinary attention.

Preparing for an Equine Health Emergency

- Keep the number of your veterinarian in your phone and near your horse’s stall, paddock/pasture, or trailer. Know if there is a different “after hours” phone number to use.

- Communicate with your veterinarian about a backup veterinarian in case your veterinarian/practice is unavailable.

- Know the route and phone numbers to the closest equine hospital/surgical center for cases that require transportation to a veterinary referral center.

- Have a list of friends or neighbors who may be able to assist in providing first aid care while you wait for the veterinarian.

- Prepare and familiarize yourself with a first aid kit for use in the barn/equine facility, in the horse trailer, and even while out on a trail. Keep it stored in a clean, dry, and easily accessible place and ensure that other barn users are familiar with its contents and location.

Healthy Horse Vital Signs

Vital signs outside of normal range could indicate illness or discomfort and warrant veterinary attention. See Figure 1 (Healthy Horse Vital Signs).

Credit: Sally Anne L. DeNotta, UF College of Veterinary Medicine, and Carissa Wickens, UF/IFAS Department of Animal Sciences; designed by Aly Morrison, UF/IFAS Center for Public Issues Education in Agriculture and Natural Resources.

Normal Physical Examination Findings

See Figure 2 (Physical Exam of the Horse) for information regarding performing a physical examination on your horse. Other important observations to make if you suspect your horse is ill or injured include:

Credit: Sally Anne L. DeNotta, UF College of Veterinary Medicine, and Carissa Wickens, UF/IFAS Department of Animal Sciences; designed by Aly Morrison, UF/IFAS Center for Public Issues Education in Agriculture and Natural Resources.

- Attitude or alertness

- Bright, quiet, lethargic, dull/depressed

- Response to normal stimuli, head carriage, awareness of surroundings

- Signs of distress

- Restlessness, pawing, circling, getting up and down, frequent rolling, looking at abdomen, kicking at abdomen, parking out as if to urinate (and either straining to urinate or not attempting to urinate)

- Respiratory character, respiratory distress, difficulty breathing

- Nostril flaring, “panicked” look, increased abdominal “heave” or effort in breathing

- Ocular discharge or squinting

- Nasal discharge

- Evidence of lameness or willingness/ability to walk

- Evidence of incoordination or loss of balance

- Presence of wounds, bleeding, or swelling

- Appetite and water intake

- Normal, reduced, any changes

- Urination/defecation

- Any recent changes or differences compared to “normal”

- Fecal consistency and quantity

- Normal, dry, loose, diarrhea, absent feces

Recognizing and Managing a Horse Health Emergency

Below is a list of commonly encountered equine emergencies and things to do and not to do while you wait for your veterinarian. This is not a comprehensive list of equine emergencies.

Colic

Colic is abdominal pain or discomfort in horses. Colic is not one specific disease, but rather a symptom resulting from an abnormal condition within the abdomen. Colic most commonly refers to conditions within the gastrointestinal tract, but not always.

Signs of colic include anorexia or reduced appetite, lethargy, depression, lying down more often, constant rolling (Figure 3), flank watching, kicking at abdomen with hindlimbs, parking out and not urinating, lip curl (Flehmen response), reduced fecal output, and mucus-covered fecal balls.

Credit: Diego De Gasperi, UF College of Veterinary Medicine.

The severity and level of necessary veterinary intervention (medical or surgical) varies greatly depending on the exact cause of the colic.

Do’s:

- Remove all food and allow the horse to drink water.

- Allow the horse to lie down quietly.

- Take the horse for brief walks if possible.

- Use pain medication (flunixin meglumine, Banamine®) only with veterinary advice regarding dose and route.

- If signs resolve without veterinary intervention, withhold feed for 12–24 hours and gradually refeed over 3–5 days, starting with small, frequent meals.

- Monitor for adequate manure production (8–12 piles/day is normal depending on specific diet).

Don’ts:

- While you are waiting for the veterinarian, do not allow the horse to eat, even if the horse is showing interest in feed.

- Do not walk the horse to the point of exhaustion (yourself or the horse).

- Do not force or syringe feed (food, water, mineral oil, etc.).

- Do not try to pass a nasogastric tube or garden horse to give water or mineral oil; this will almost certainly cause inadvertent inhalation (or aspiration) of these contents into the lungs.

- Do not give flunixin meglumine/Banamine® intramuscularly (IM).

- Do not give additional doses of pain medication without veterinary advice.

- Do not refeed too soon or with too much food. You should consult with your veterinarian for specific instructions prior to initiating refeeding. Typically, slow and gradual refeeding is done to ensure the gastrointestinal tract can adequately handle the feed. Horses that have resolved colic should appear very eager and hungry for food during the refeeding period and continue to produce feces.

- Note that during gradual refeeding, horses generally will not produce the “normal” quantity of feces due to intentionally reduced feed intake.

Choke

Esophageal obstruction, or “choke,” is a relatively common problem that occurs in horses when food (or a foreign object) is lodged in the esophagus and creates an obstruction. The esophagus is a tube that allows passage of food and water from the mouth down into the stomach. It is not a blockage of the trachea (or windpipe) as it is in humans. When a blockage occurs, food and water cannot pass down into the stomach, and can accumulate within the esophagus if the horse attempts to continue to eat and swallow. Clinical signs include saliva and/or food out of the nostrils (Figure 4), retching, coughing with saliva, and potentially a visible and/or palpable bulge in the neck. Horses may appear anxious, depressed, or uncomfortable.

Credit: Chris L. Sanchez, UF College of Veterinary Medicine.

If you believe your horse has choked, do not panic. The horse does not have an obstruction of its windpipe and is able to breathe normally. Many simple cases resolve on their own within a couple of hours without veterinary intervention. Evidence of choke resolution will include cessation of feed material and saliva exiting the nose. Horses may appear “brighter” when the blockage clears.

Risk factors for choke include poor dentition/improper mastication (chewing), reduced saliva production (in geriatric horses), improper feed, large-pelleted feeds/shavings/dried beet pulp, ravenous eating habits (bolting), excitement in a new environment (show, hospital, etc.), exhaustion (rest stops), sedation with permission to eat, and foreign bodies. Potential complications include aspiration pneumonia, or inhalation of feed, saliva, and water into the lungs that causes a bacterial infection. Depending on the severity and duration of the choke, the esophagus can endure trauma including ulcerations, tears, or lacerations. If these lesions are present, they may result in permanent scarring or narrowing (stricture) which can predispose the horse to further choke episodes.

Do’s:

- Move the horse to an empty stall or small pen if possible.

- Remove all available food and water.

- Ideally, the horse should be kept in a non-bedded stall or dry lot. If that is not possible, the horse should have a muzzle placed to prevent consumption of feedstuffs or bedding.

- If there is a visible bulge in the horse’s neck, you may try to gently massage it.

- Contact your veterinarian to discuss the specifics of the case and determine whether veterinary intervention is needed.

- Monitor the horse for coughing, increased respiratory rate and/or effort, nasal discharge, fever (>101.5°F), depression, or loss of appetite in the days after a resolved episode of choke.

Don’ts:

- While you are waiting for the veterinarian, do not allow the horse to eat or drink, even if the horse shows interest in feed.

- Do not try to pass a nasogastric tube or garden hose to give water or mineral oil; this will almost certainly cause inadvertent inhalation (or aspiration) of these contents into the lungs.

- Do not forget about follow-up veterinary care, which may include blood work, ultrasound of the lungs, or endoscopy of the esophagus.

- Do not refeed too soon after a resolved episode. Consult with your veterinarian for specific instructions prior to initiating refeeding. Typically, slow and gradual refeeding with gruel/mashes is recommended to provide reduced roughage through the esophagus.

Eye Injury

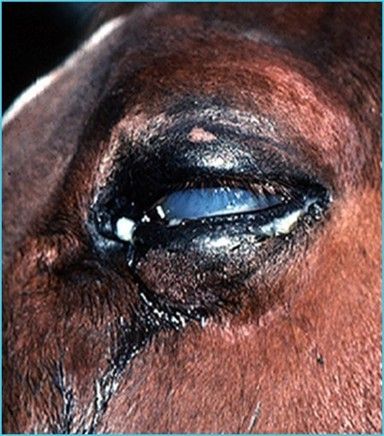

Horses are prone to eye injuries due to the prominent physical position of their eyes, their curious and flighty nature, and exposure to contaminants near their eyes (e.g., bacteria or fungi in their local environment). If you suspect something abnormal with one eye, you can use the other eye to compare. A normal horse eye should be wide open, with eyelashes parallel to the ground, a shiny and clear/transparent surface, and no swelling or discharge. Abnormal horse eyes may have excessive squinting, closed or partially closed eyelids with vertical/downward deviation of eyelashes, discharge (clear, mucus, pus, etc.), swelling of one or both eyelids, abnormal surface (haziness, cloudiness, blue), or visible blood vessels on the surface (Figure 5).

Credit: Caryn E. Plummer, UF College of Veterinary Medicine.

Common problems include trauma (directly to the eyeball or globe, or head trauma), ulceration, sudden loss of vision, foreign bodies, or wounds around the eye (involving eyelid margins).

Do’s:

- Wear gloves.

- Gently perform lavage on (i.e., clean) the eye and surrounding tissue with eye wash or saline.

- You may also use dilute betadine solution (weak tea color) as this will not harm the eyeball.

- Keep damaged surrounding tissue moist to retain viability for potential surgical repair.

- Consult with your veterinarian prior to applying anything into the eye. Generally, triple antibiotic eye (ophthalmic) ointment or silver sulfadiazine cream (SSD) can be applied into the eye and on surrounding tissue.

- SSD has both antibacterial and antifungal properties.

- Place a fly mask or an eye saver to prevent further contamination; try to prevent self-trauma from scratching or rubbing.

- Seek veterinary advice with any abnormalities because eye problems can become serious very quickly.

Don’ts:

- Horses have strong eyelids — do not force them open.

- Avoid "digging" around in eye tissue.

- Do not clean in or near eyes with chlorhexidine or alcohol — both are toxic to eyes.

- Do not apply eye ointments without veterinary advice.

- This is especially important with steroids (dexamethasone, hydrocortisone, prednisolone) and even atropine.

- Do not delay veterinary evaluation — eye injuries are serious.

Respiratory Distress/Difficulty Breathing

True respiratory emergency conditions lead to respiratory distress. Conversely, there are life-threatening conditions without respiratory distress (e.g., pleuropneumonia and aspiration pneumonia) that will not be discussed here. The respiratory system is traditionally divided into upper and lower tracts. The upper respiratory tract includes the nostrils, nasal passages, pharynx, larynx, sinuses, and guttural pouches. The lower respiratory tract includes the trachea and airways leading into the lungs, and the lungs.

Horses are obligate nasal breathers, meaning they cannot switch to open-mouth breathing like many animals. Upper airway respiratory distress is often a result of obstruction of some part of the upper airway, often causing difficulty during the inspiratory phase of breathing (inhalation). Causes include trauma, foreign bodies, laryngeal swelling, anaphylactic reaction, snake bite/bee sting, upper respiratory infectious diseases (e.g., strangles/Streptococcus equi equi), and masses.

- Listen for noisy breathing (stertor or stridor), which is a sign of turbulent air flow.

- Feel for airflow through one or both nostrils. Lack of or limited airflow indicates an obstruction.

- Look for nostril flaring during inspiration.

- These conditions are often rapidly progressive due to swelling and turbulent airflow through the compromised airway.

Lower respiratory distress can be caused by equine asthma, pulmonary edema, and pneumothorax (or air inside the chest cavity).

The treatment principles are extremely dependent on location and etiology of respiratory distress. Veterinary advice and evaluation should be initiated immediately.

Do’s:

- If you suspect upper airway obstruction or the horse’s nose starts to swell, a tube should be inserted into the nostril to keep the nasal passage open.

- Owners can perform this in the field using a flexible tube with soft edges (e.g., a cut water hose with softened edges).

- Measure the distance from the inside corner of the eye to the nostril and cut the tube to this length.

- Lubricate the tube, gently pass it into the nostril, and tape it in place. Ideally, a tube should be placed into both nasal passages (Figure 6).

- This will keep the nasal passages open while you wait for veterinary attention.

Credit: Shannon Darby, UF College of Veterinary Medicine.

- Open wounds on the thorax and signs of respiratory distress may indicate an open pneumothorax (meaning there is communication from outside into the chest cavity, which causes the chest cavity to expand with air and prevents the lungs from functioning normally).

- Cover any wounds with occlusive dressing (e.g., Saran wrap) to prevent further accumulation of air into the wound.

- Equine asthma (lower airway bronchoconstriction) may have historical diagnosis and expiratory difficulty with or without coughing.

- Do not force movement.

- Remove the horse from any hay/dust.

- If there are previously prescribed medications for your horse and this condition, contact a veterinarian and administer the medications if recommended.

Snake Bite/Envenomation

Pit vipers (Crotalinae) are responsible for snake bite envenomation in horses in North America. Pit vipers are aptly named for characteristic heat-seeking pits between their eyes and nostrils. They have triangular heads due to venom gland location, retractable fangs to inject venom, and elliptical pupils. The pit vipers in North America are rattlesnakes, copperheads, and cottonmouths/water moccasins.

Another type of venomous snake family (Elapidae) contains coral snakes and is not reported to cause envenomation in horses in the United States (although members of this snake family do cause envenomation in companion animals).

If you suspect your horse has encountered a snake, proper snake identification is extremely helpful. Consult Ask IFAS publication WEC 202, “Recognizing Florida’s Venomous Snakes,” at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/UW229 (Johnson and Main 2024).

Envenomation causes varied clinical signs and disease severity depending on the location of the bite and amount of envenomation. The following are often seen with snake bites:

- Local tissue swelling (acute and painful edema) occurs at the bite site, which may later result in necrosis.

- Muzzle bites are most common, followed by lower limb bites.

- The actual punctures may or may not be visible.

- Cases of snake envenomation in horses, particularly those that occur on the head/muzzle, become true immediate medical emergencies due to the potential for rapid facial swelling that compromises breathing. Progressive swelling leads to upper airway respiratory obstruction that may require a tracheostomy (Figure 7).

- Light-colored skin may develop bruising and/or frank bleeding, and spontaneous bleeding may occur from eyes, ears, nose, injection sites, etc.

Credit: Martha Mallicote, UF College of Veterinary Medicine.

Do’s:

- Seek veterinary advice.

- Maintain an open airway. If you suspect upper airway obstruction or the horse’s nose starts to swell, a tube should be inserted into the nostril to keep the nasal passage open.

- Owners can perform this in the field using a flexible tube with soft edges (e.g., a cut water hose with softened edges).

- Measure the distance from the inside corner of the eye to the nostril and cut the tube to this length.

- Lubricate the tube, gently pass it into the nostril, and tape it in place. Ideally, a tube should be placed into both nasal passages (Figure 6).

- This will keep the nasal passages open while you wait for veterinary attention.

- Note: Pain, inflammation, and tissue necrosis secondary to the snake bite may make passage difficult. Therefore, it is best to perform this step as soon as swelling is identified. Do not wait for swelling to progress further prior to placement of tubes.

Don’ts:

- Do not administer any medications (NSAIDs, antibiotics, or steroids) without veterinary advice.

- If the horse is bitten on the limb and swelling occurs, do not force movement.

- The following historically recommended treatments may worsen tissue injury and should not be performed:

- Tourniquet

- Venom extraction

- Bite site excision

- Aggressive cryotherapy (icing) of the bite wound

Heat Exhaustion and Heat Stroke

The primary method that horses utilize to maintain an appropriate internal body temperature is sweat evaporation. As sweat evaporates from the skin, it facilitates cooling of the body temperature. Heat exhaustion and heat stroke in horses occur when a horse is unable to dissipate heat in hot and humid environments. They are often combined with a pre-existing impaired sweating response (anhidrosis) or an acute inappropriate sweating response related to the ambient temperature. Oftentimes, this occurs during high-intensity exercise or prolonged submaximal exercise in hot and humid conditions.

Signs of heat exhaustion in horses include rapid and shallow breathing, increased respiratory effort, flared nostrils, high heart rate, profuse sweating, or hot and dry skin. The horse may refuse to work, experience reduced appetite, demonstrate depression, weakness, and incoordination, and collapse. Rectal temperatures ranging between 103°F and 106°F are consistent with heat exhaustion/stress, whereas temperatures ranging between 106°F and 110°F are consistent with heat stroke. If heat exhaustion goes untreated, it can progress to heat stroke, which is a more serious condition that can result in multiple organ dysfunction and death.

Do’s:

- Move the horse to a shaded, well-ventilated area and add fans.

- Decrease body temperature — the faster the better.

- Apply cold or ice water over the entire body continually. If cold or ice water is unavailable, tap water from the garden hose is acceptable (Figure 8).

- Apply ice packs over the carotid area of the horse’s neck.

- Horses have such a large surface area that it is not feasible to cool them too quickly. This contrasts with companion animals and humans who require gradual cooling.

Credit: Laura Patterson Rosa, Long Island University College of Veterinary Medicine.

- Offer lukewarm, cold, and electrolyte water buckets for drinking.

- Recheck temperature frequently.

Don’ts:

- Do not scrape the water off, just continually apply.

- Recent research has demonstrated greater reductions in body temperature when water was not scraped off between applications (Kang et al. 2023).

- Do not use wet towels or fabric covers because they prevent heat convection.

- Do not force the horse to walk; voluntary movement is acceptable.

- Do not withhold drinking water.

- Do not use NSAIDs without veterinary advice.

- Do not continue cooling strategies once the horse’s temperature reaches 101°F–102°F.

Blood Loss

Acute external blood loss most often occurs secondary to trauma or laceration where a major vessel is involved. Guttural pouch mycosis (fungus) may result in a life-threatening nosebleed. The degree of bleeding from a vessel is dependent on the type of vessel (venous is lower pressure; arterial is higher pressure). Unfortunately, if a major arterial vessel is involved (i.e., femoral or carotid artery), the horse can bleed a dangerously large amount in a matter of minutes. Early and prompt hemorrhage control is the main priority. Many bleeding wounds are not initially life-threatening but may become life-threatening with delayed hemorrhage control. Note that internal hemorrhage has different causes and treatment principles. Clinical signs of significant blood loss include increased heart rate, increased respiratory rate, pale gums/mucous membranes, and weak peripheral pulses.

While any degree of blood loss can appear alarming, and hemostasis should be initiated immediately, it is important to recognize how much blood is “too much blood.”

- 8% of the horse’s body weight is blood.

- A 1,000-pound horse has 80 pounds of blood = 36 liters (9.5 gallons).

- A 1,250-pound horse has 100 pounds of blood = 45 liters (11.9 gallons).

Horses can lose approximately 25% of blood volume before any critical issues arise:

- 9 liters in a 1,000-pound horse (2.4 gallons)

- 11.25 liters in a 1,250-pound horse (~3 gallons)

Do’s:

- Direct pressure is the most effective “medical” intervention for initial control of external blood flow.

- Apply a thick circumferential pressure bandage.

- If blood soaks through, apply an additional bandage on top of the first bandage.

- When feasible, splint (immobilize) the bleeding extremity for extra control.

- This should be performed in addition to direct pressure.

- Elevation of an extremity is not feasible in the adult horse.

- Discourage movement because it can disrupt potential clot formation.

- Call the veterinarian for surgical repair of the damaged vessel.

Don’ts:

- Do not remove the pressure bandage to clean the wound; the clot may be disrupted, and hemorrhage may resume.

- Do not place excessively tight or restrictive circumferential compressive bandages around neck, thorax, or abdomen.

- This could occlude the airway or restrict chest expansion and impair respiration.

- Do not apply a tourniquet as the first line of hemorrhage control because it may dangerously decrease blood flow to the extremity.

- This should only be used as a last resort if the hemorrhage continues despite other methods.

Acute Non-Weight-Bearing Lameness

Severe and sudden non-weight-bearing lameness has several potential causes, results in a significant amount of pain, and manifests as reluctance to move or bear weight on the limb. Typically, conditions that lead to this severe degree of pain affect a single limb at a time. The exception is laminitis, which commonly affects two or more feet at a time.

If the horse has a sudden onset of non-weight-bearing lameness, investigate for swelling or wounds. Palpating digital pulses in the foot is a helpful indicator of pain or inflammation of the digit.

Subsolar Abscess

Subsolar abscesses, or hoof abscesses, result in sudden severe lameness, equivalent to that of a limb “fracture.” This occurs when there is an accumulation of pus underneath the sole secondary to tracking of bacteria or subsolar bruising/trauma. Additionally, pus may track upwards and erupt from the coronary band.

The horse may hold up the foot or point the toe, and there is often significant heat in the affected hoof with increased digital pulse. There may be lower limb swelling, as cellulitis can be common with subsolar abscesses. There may be a soft or moist “spot” on the sole with or without an identifiable tract. Evaluate the coronary band for a tract.

Do’s:

- Remove the horse’s shoe (if possible).

- Soak the foot to soften the keratinized tissue/hoof.

- Bucket, bag, large soaking boot

- Epsom salt, iodine, many options

- Place a poultice bandage, such as Animalintex®.

- The goal is to establish drainage to the bottom of the foot or sole.

- Keep the area clean and prevent recontamination using a watertight foot bandage.

- Dry/desiccate the abscess cavity.

- NSAIDs are often necessary due to non-weight-bearing lameness. Consult your veterinarian.

- Discuss a tetanus toxoid vaccine booster with your veterinarian.

Don’ts:

- If gently exploring or probing the region, do not remove healthy tissue to locate the tract.

- Soak or bandage overnight with poultice to moisten the sole.

- Do not rule out a potential fracture or septic joint if an abscess tract cannot be identified.

- Do not allow abscesses to go untreated because they may lead to bone or joint infection.

Penetrating Hoof Wound

This typically occurs when a nail penetrates the sole and can result in variable lameness. The puncture site can be difficult to identify unless the penetrating object is in place. Punctures that occur in the back one-third of the sole are at increased risk of communicating with joint/synovial structures or bone. Penetrating objects are inherently contaminated (e.g., feces, soil, bacteria) and can lead to a life-threatening infection.

Do’s:

- If a foreign body is still present, leave it in place.

- Attempt to “bend” the foreign body or cut it off to prevent further penetration (it is better to take X-rays with the object in place).

- Apply a foot bandage to minimize additional contamination.

- If the horse requires transport and the object must be removed, circle the penetrating region so that the veterinarian can identify its location.

- Consult with a veterinarian immediately and discuss initiation of antimicrobials or NSAIDs.

- The veterinarian may recommend delaying antimicrobials if referral to a hospital is imminent.

- Discuss a tetanus toxoid vaccine booster with your veterinarian.

Don’ts:

- Do not remove the foreign object if possible.

- Do not assume that the penetration is superficial or non-life-threatening because it is small.

- Do not avoid veterinary evaluation for conservative soaks and bandaging.

- Do not delay referral if deeper structures are a concern.

Painful Single-Limb Swelling

Acute inflammatory edema of the limb results in a large/swollen, hot, and painful leg. These are referred to as “stovepipe” legs. Depending on the origin of the edema, there may be inflammation of blood vessels, lymph vessels, or subcutaneous tissue. The result is “pitting edema” wherein a dimple or depression can be created when pressure is applied and removed, which results in a painful or resentful response from the horse. The horse often experiences high levels of pain, is lame on the affected leg, and may have a fever (rectal temperature >101.5°F–102°F). Cellulitis, or inflammation of the subcutaneous tissue, is likely the most common cause of acute painful single-limb swelling. Causes include wounds, scratches (pastern dermatitis), and local reaction to injection or contact allergen; additionally, there may be no obvious inciting cause. The swollen tissue can also be infected. Thus, antimicrobials may be recommended by the veterinarian for treatment. Treatments and prognosis are variable because this condition can range from mild to severely painful with aggressive progression.

This condition contrasts with “stocking up,” which is non-painful subcutaneous edema. Usually, it affects both hindlimbs, or even all four limbs, and is associated with a recent decrease in exercise (i.e., stall rest). The condition does not typically warrant veterinary treatment.

Do’s:

- Perform hydrotherapy (frequent and cold water).

- Encourage movement.

- Muscle contraction and elevating blood pressure help to move blood and lymph fluid back to the heart.

- The equine lower limb has no muscles to contract. One-way valves in vessels hold the fluids and compression of the frog propels them upward.

- Administer NSAIDs (with veterinary guidance).

- Systemic (flunixin meglumine, phenylbutazone) and/or topical (diclofenac).

- Additional pain medications may be necessary because horses can experience high levels of pain.

- Bandaging provides support and compression.

- A sweat bandage may be used with veterinary guidance.

- Use veterinarian-prescribed products or equine-specific products to avoid inadvertently damaging or burning the skin.

- Sweats should not be applied over wounds/lacerations.

- Wear gloves when handling topical sweat.

- When bandaging, be cautious over bony prominences (hock and carpus/knee).

- Seek a veterinary consultation for an individualized treatment plan.

Don’ts:

- Do not bandage without proper technique or material. Improper technique or material:

- Can cause damage to underlying structure(s).

- Can create bandage sores.

- Can encourage inappropriate fluid collection above the bandage.

- Do not initiate antibiotics, NSAIDs, or steroids without veterinary advice.

- Do not delay veterinary intervention.

Fracture or Joint Luxation

Fractures and luxations are often the result of a kick or fall. The prognosis and degree of lameness are dependent on the bone involved and the type of fracture or luxation. Horses may be unwilling to move or may continue to try to place weight on the limb. They may appear distressed or panicked and may have excessive sweating, shaking, and increased respiratory rate or effort. There may be concurrent wounds, limb swelling, or a break in the skin with exposed bone (open fracture).

Do’s:

- Immediately restrain and calm the horse.

- You can use a twitch.

- Use sedation and pain medication with caution.

- These may cause undesired wobbly gait or incoordination.

- The horse may overuse the limb and worsen the fracture.

- Consult with your veterinarian and apply a splint if recommended.

- There are specific splints for specific fracture types.

- If an open fracture is present, clean the wound carefully and prevent further contamination with a bandage.

- Discuss a tetanus toxoid vaccine booster with your veterinarian.

Don’ts:

- Do not transport the horse without applying a proper splint.

- Failure to apply a proper splint before transport significantly reduces the chance of successful repair.

- Do not indiscriminately use sedation or pain medication.

- Do not drive too quickly.

Transportation:

- Always apply external coaptation first.

- Ideally, face forelimb fractures backwards and face hindlimb fractures forward.

- Confine the horse so that it cannot turn around.

- Loosely tie the head so it can be used for balance.

- Providing hay may help to relieve anxiety.

- Frequent stops should be made to check on the status of the horse and provide drinking water.

Injury/Puncture Wound Over a Joint

When a wound or laceration communicates with a joint or synovial structure (e.g., tendon sheath), it is always an emergency. The size of the wound does not matter in determining the significance of the condition (large laceration vs. puncture). The horse may initially be comfortable, but lameness will develop as the joint or synovial structure becomes infected. If a wound occurs around or over a joint (Figure 9), communication should always be suspected until it is ruled out by a veterinarian.

Credit: © patb56 / Adobe Stock.

Do’s:

- Move the horse to a clean, dry environment.

- Gently clean the wound and cover it with a light bandage.

- Call the veterinarian.

- Discuss a tetanus toxoid vaccine booster with your veterinarian.

Don’ts:

- Do not assume the synovial structure is unaffected just because the horse is weight-bearing.

- Do not wait to see how the horse responds to conservative therapy before having synovial communication assessed.

Wounds and Lacerations

Generally speaking, the following signs indicate a concerning wound or laceration that should be evaluated by a veterinarian:

- Deep wound with flap of skin

- Wound (big or small) near a joint or synovial structure

- Exposed bone

- Significant bleeding

- Other discharge from the wound

- Pus, clear or sticky fluid

- Lameness

- Swelling

- If the horse was kicked

- Facial wounds involving the airways or eyes

- If the wound is not healing or is becoming worse

- Proud flesh (exuberant granulation tissue) develops

Wounds or lacerations with the following signs may be fine without veterinary intervention:

- Just loss of hair

- Intact skin

- No skin flap

- Not near a joint

- No lameness

- Minimal swelling

Do’s:

- Seek veterinary advice about the specific laceration/wound:

- Note: “Fresher” wounds are easier to repair.

- Dry and dead tissue is not viable for repair.

- Fresher tissue will have a higher likelihood of suture success and adequate healing.

- Suture failure will lead to wound dehiscence.

- Consult with the veterinarian if obvious wound contamination is present.

- If possible, clip the hair and gently clean.

- Apply lube within the wound prior to hair clipping.

- Clean with saline or tap water. Avoid using soaps.

- Keep the wound clean and dry and lightly bandage it while waiting for the veterinarian.

Don’ts:

- Do not avoid veterinary evaluation if you have any concerns.

- Do not clean with soaps, detergents, or alcohol.

- Do not apply sprays, creams, or powders if you are waiting for veterinary assistance; these may impede closure.

NSAID Best Practices

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly used in equine patients to help relieve pain, decrease inflammation, and control fever. NSAIDs are readily available and cost-effective medications and are a mainstay in the management of many painful and inflammatory conditions in horses. Despite their common use, they have serious potential adverse effects that can result in death. Therefore, NSAID use should only occur under veterinary direction. The NSAIDs used in horses are phenylbutazone (“bute”), flunixin meglumine (Banamine®), and firocoxib (Equioxx®).

Do’s:

- Prudent use of these medications is essential.

- Always seek veterinary advice regarding indication, dose, route, and frequency.

Don’ts:

- Do not “stack” NSAIDs (i.e., do not give more than one type of NSAID together).

- Do not give bute intravenously (IV).

- Tissue necrosis will occur if the drug is out of the vein.

- Do not give flunixin meglumine in the muscle (IM) — only administer it orally.

- Potentially fatal muscle infection may occur.

- Do not use without veterinary advice regarding dosing, frequency, side effects, etc.

- Possible complications include gastric ulceration, colitis, and kidney disease.

- These diseases can range in severity but can ultimately lead to death.

Bandaging Techniques

Bandage Functions

- Protect wounds from contamination

- Protect tissue from drying

- Immobilize skin edges

- Reduce swelling or hemorrhage

- Stabilize/immobilize underlying structures

Layers of a Standard Bandage

- Beginning as the first layer, apply the appropriate wound dressing. Hold in place by soft, lightweight padding such as thin white gauze.

- Next, apply a layer of cotton padding (e.g., 3M Gamgee®) that provides padding and support and absorbs wound exudate.

- Apply gauze weave over the cotton to keep it in place.

- Finally, use an adhesive bandage to protect the wound from external contaminants and to secure the bandage (often Vetrap® first over gauze weave [not extending beyond cotton], and then Elastikon® to secure above and below the wrap directly to the skin or hoof).

Tips

- Remove dirt, debris, soap residue, or moisture to prevent skin irritation and dermatitis.

- Start with clean, dry legs and bandages. Do not wrap wet legs.

- If there is a wound, make sure it has been properly cleaned, rinsed, and dressed according to your veterinarian's recommendations.

- Start the wrap at the inside of the cannon bone above the fetlock joint.

- Do not begin or end over joints because movement will tend to loosen the bandage and cause it to unwrap.

- Wrap in a spiral pattern, working down the leg and up again, overlapping the preceding layer by 50 percent.

- Use smooth, uniform pressure on the support bandage to compress the padding.

- Make sure no lumps or ridges form beneath the bandage.

- Leg padding and bandages should extend below the coronet band of the hoof to protect the area. This is especially important when trailering.

- Extend the bandages to within one half-inch of the padding at the top and bottom.

- There is no scientific evidence to support the “correct” direction, but generally, people expect the following: Start from inside and wrap to the front of the leg.

- Clockwise on right legs and counterclockwise on left legs.

- Be careful over bony prominences (hocks, carpi/knees); bandage rubs are serious.

- Change bandages daily. Change them sooner if they are soiled, slipping, or soaked through.

- Sweat bandage: Apply horse-specific sweat material directly to skin, and gently lay plastic material (Saran Wrap®) on top in smooth layers that do not constrict. Continue to wrap as usual.

- Practice makes perfect.

Robert Jones Bandage

This is a pressure bandage made up of multiple layers of soft, compressible materials. It may be used in conjunction with the appropriate splint(s). The purpose of the bandage is to provide stabilization for a lower-limb fracture or luxation. Consult with your veterinarian for appropriate bandaging and splinting depending on the suspected fracture location.

The bandage should extend from the hoof to the top of the leg and hold each joint still. Ideally, it will be 1.5 times the circumference of the leg. It is best to have a team for this kind of bandage (i.e., one person to restrain the horse, one person to apply the bandage, and one person to pass the bandage materials). The goal is to have a thick and tight bandage. When you tap the completed bandage, it should sound like a ripe melon. You may have to be creative with bandage supplies (towels, pillows, etc.). Horses may react undesirably to having a thick full-limb bandage, so use caution after bandage completion when the horse takes the first several steps.

Materials:

- Light bandage over wound or open fracture

- 6–8 rolls of 1-lb cotton roll

- 4–6 rolls self-retaining wrap (Vetrap®)

- 4–6 rolls elastic tape/Elastikon® (4–6 inches)

- You may also use 1–2 ACE bandages (6 inches)

- Broom handles or PVC pipe, something sturdy for splint if needed

- Duct tape (2-inch width)

Hoof Bandage and Poultice

Steps:

- Animalintex® poultice: Cotton wool impregnated with an antiseptic draws out abscess. The backing helps retain moisture and warmth and protects the wound from external contamination. The shiny side backing should be oriented away from the surface of the hoof.

- Wrap a small baby diaper around the hoof.

- Secure the diaper with a self-retaining bandage (Vetrap®). Do not restrict the coronary band.

- Premake a duct tape patch: 4–6 strips side by side, repeat additional 4–6 strips at 90 degrees. Place the patch on the bottom of the hoof over Vetrap®. Secure corners by wrapping around the hoof, but do not stick to skin/coronary band.

- Prevent shavings and dirt from entering the top of the bandage with Elastikon® (directly to skin; do not apply tightly).

Table 1. First aid kit supplies (equipment, wound and injury treatments, medications, disposable bandage supplies, and reusable bandage supplies).

References

Johnson, S. A., and M. B. Main. 2024. “Recognizing Florida’s Venomous Snakes: WEC 202/UW229.” EDIS. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/UW229

Kang, H., R. R. Zsoldos, A. Sole-Guitart, E. Narayan, A. J. Cawdell-Smith, and J. B. Gaughan. 2023. “Heat Stress in Horses: A Literature Review.” International Journal of Biometeorology 67(6): 957–973. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-023-02467-7