Nonnative invasive plant species pose a significant threat to Florida's natural areas. The UF/IFAS Assessment of Nonnative Plants in Florida's Natural Areas (hereafter, UF/IFAS Assessment) uses literature-based risk assessment tools to predict the invasion risk of both nonnative species that occur in the state as well as species proposed for introduction. The UF/IFAS Assessment team has evaluated more than 900 species, including 208 species proposed for introduction or new uses. The team is actively identifying and evaluating potentially problematic nonnative species (and sub-specific or hybrid taxa). Recommendations and supporting information from the UF/IFAS Assessment can be found at http://assessment.ifas.ufl.edu.

Background

Approximately 85% of all nonnative plant species enter the United States through one of Florida's 30 ports of entry (Simberloff 1994). As international trade continues to grow, so does the frequency of intentional and accidental introductions. Only a small percentage of nonnative plants becomes invasive and causes ecological problems such as habitat degradation or biodiversity loss (Williamson and Fitter 1996). However, some introduced species become invasive, leading to high management costs and significant impacts to recreational areas, which result in economic losses. In fact, on Florida's conservation lands alone, the cost of managing invasive plants averaged approximately $45 million in FY 2009–2014 (Hiatt et al. 2019), and control costs statewide may approach $100 million per year (The Nature Conservancy 2020).

Results of the IPBES' global assessment on biodiversity and ecosystem services* determined that the number of nonnative species introduced outside their native range has doubled over the last 50 years, and approximately one fifth of the world's ecosystems are at risk of being invaded by nonnative species (Diaz et al. 2019). Globally, one million species are in danger of going extinct within decades. Invasive species have been identified as one of the five major drivers of this decline (Diaz et al. 2019). Florida is particularly vulnerable to nonnative invasive species because of its peninsular geography, tropical/subtropical climate, and diverse ecosystems. More than half of the land area in Florida is either being developed or used for agriculture. The remaining natural areas are either disappearing or the quality of protected habitat is deteriorating. Florida's natural areas are crucial to preserving rare, threatened, or endangered species endemic to the state, including the Key deer (Odocoileus virginianus clavium), Perdido Key beach mouse (Peromyscus polionotus trissyllepsis), Schaus' swallowtail butterfly (Heraclides aristodemus), pine barrens treefrog (Hyla andersonii), pygmy fringe tree (Chionanthus pygmaeus), and four-petal pawpaw (Asimina tetramera).

When we consider that Florida is home to approximately 135 threatened or endangered species, the connection between invasive species prevention and management is clear. Currently, there are approximately 1,500 nonnative plant species present in Florida (Wunderlin et al. 2020). Not all of these plants are invading Florida's natural areas at this time. However, once a species becomes invasive, ecological and economic costs can escalate. Having a tool to assess the status of nonnative species in the state can identify invasive plants, reduce associated costs, and help to prioritize management efforts. Furthermore, prevention efforts depend on a method to assess the invasion risk of a species proposed for release or recommended for more widespread use in the state before it is introduced.

The UF/IFAS Invasive Plant Working Group created the UF/IFAS Assessment in 1999 to provide status and risk assessments for nonnative species in Florida's natural areas. The purpose of the UF/IFAS Assessment is to decrease invasion into natural areas by ensuring that plant species with invasive characteristics are not recommended for use by UF/IFAS faculty or staff. In the context of the UF/IFAS Assessment, an invasive species is defined as a species that is nonnative to the ecosystem and whose introduction causes or is likely to cause economic or environmental harm or harm to human health. Additionally, invasive species can form (or have a high probability of forming) self-sustaining and expanding populations in a natural plant community with which they had not previously been associated (cf. "invasive") (Vitousek et al. 1995).

The UF/IFAS Assessment is an integral element of the university's Extension efforts. UF/IFAS faculty members rely on the recommendations of the UF/IFAS Assessment when discussing the use of nonnative plants. In fact, any UF/IFAS Extension publication or newsletter that refers to specific nonnative plants (e.g., invasiveness, ecology, distribution, management, use, and value) is required to include the recommendations of the UF/IFAS Assessment. Information about how to cite components, conclusions, and results of the UF/IFAS Assessment can be found at http://assessment.ifas.ufl.edu under FAQs. UF/IFAS Extension programs such as the Florida-Friendly LandscapingTM Program and the Florida Master Gardener Volunteer Program incorporate UF/IFAS Assessment conclusions in their programs (e.g., Florida Friendly Plant Database, Florida Friendly Yard Recognition Program). Land managers, industry, and the general public also utilize the conclusions of the UF/IFAS Assessment when deciding on the use and management prioritization of nonnative species in Florida. The UF/IFAS Assessment is also now providing recommendations to the Florida Invasive Species Council's (FISC) plant listing process (formerly Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council)**. This has resulted in better continuity between the two non-regulatory lists. Additionally, the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS) consults with the UF/IFAS Assessment to evaluate proposed biomass and bioenergy crops as a part of its biomass planting rule (5B-57.0110), and when FDACS considers regulating plants as noxious weeds. Landowners, managers, and industry turn to the UF/IFAS Assessment when deciding on the use of nonnative species in Florida, and the tools employed by the UF/IFAS Assessment have been internationally recognized as models for evaluating nonnative species (Fox, Gordon, and Stocker 2003; Gordon et al. 2008a; Fox and Gordon 2009).

The UF/IFAS Assessment consists of three components: the Status Assessment, the Predictive Tool, and the Infraspecific Taxon Protocol. The Status Assessment evaluates the invasiveness of nonnative species that currently occur in Florida's natural areas. The Predictive Tool is a risk assessment model based on the Australian Weed Risk Assessment (WRA) that was modified to specifically account for Florida's climate and geography (Gordon et al. 2008b). The Predictive Tool determines the invasion risk of species that are not currently found in Florida's natural areas but are invasive in other places with similar climate and growing conditions. The Predictive Tool also evaluates new uses of species that may increase the number of seeds (or other viable propagules) in the landscape (e.g., bioenergy crops). The Infraspecific Taxon Protocol (ITP) evaluates the invasive potential of horticultural and agricultural selections, hybrids, and cultivars. This tool was developed to determine if this invasive potential differs from that of the invasive parent species found in Florida, regardless of whether they occur in natural areas or are grown in cultivation ("resident species"). Since the UF/IFAS Assessment was first implemented, more than 900 plant species have been evaluated with one or more of these tools.

Status Assessment

The Status Assessment provides a system to determine if a nonnative plant species is (or is at risk to be) invasive in Florida's natural areas. Recommendations reached through the Status Assessment are intended to prevent invasions and limit the spread of current invasions. The Status Assessment is intended only for plants that currently occur in Florida and is not intended to provide evaluations of species that have not yet been introduced to the state. Proposed species and novel or infraspecific taxa would be assessed using the Predictive Tool or the ITP. For more information, see these sections below.

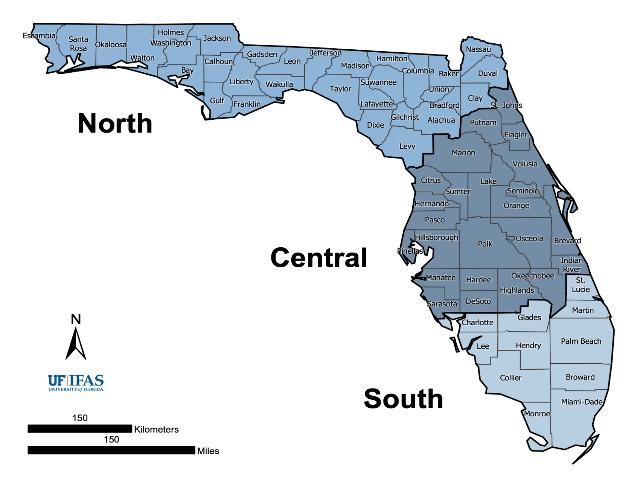

To account for differences in how a species will perform in different regions of the state, Florida has been divided into three zones—North, Central, and South. These zones are approximate USDA hardiness zones (http://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/PHZMWeb/), and conclusions are developed for each zone independently (Figure 1). For example, some species may be invasive in all parts of the state, while others are limited to particular zones (e.g., subtropical south Florida or the Panhandle). Species are systematically re-evaluated to document changes in their status, and conclusions are amended when necessary.

Credit: Adapted from Wunderlin (1982). Map prepared by Seokmin Kim, 2020.

The Status Assessment consists of questions about ecological, management, and economic aspects of the species and the species' potential to expand into non-invaded zones. At least three experts (i.e., land managers or scientists) in each region familiar with the status of the species complete questionnaires for the Status Assessment. These experts provide the following information:

- Distribution of the species (i.e., how many acres are occupied by the species and which habitat types are invaded)

- Long-term alterations to ecosystem processes (i.e., changes in fire regimes, negative impacts to threatened and endangered species, and changes in community structure)

- Life history traits related to fecundity (i.e., number of viable propagules, time to reproductive maturity)

- Management practices (i.e., which management methods are used, difficulty in implementation, and cost)

- Estimated economic value of the species (i.e., is it sold in stores, is it a crop species, is it used as forage, biomass, or for remediation purposes)

Their responses are incorporated with information gathered from an extensive literature search (herbaria records, peer-reviewed primary literature, floras) to reach UF/IFAS Assessment final recommendations.

There are four possible results of the Status Assessment:

- Not considered a problem species at this time, may be recommended

- Caution, may be recommended but manage to prevent escape

- Invasive and not recommended except for "specified and limited" use approved by the UF/IFAS Invasive Plant Working Group (this conclusion is rare)

- Invasive and not recommended

The conclusions include plans for reassessment, after either 2 or 10 years (every 10 years for results 1 and 4, and every 2 years for results 2 and 3). Any species may be reassessed upon request whenever additional relevant information becomes available that might change the conclusions of the Status Assessment.

Predictive Tool

The purpose of the Predictive Tool is to decrease invasions in Florida's natural areas by ensuring UF/IFAS faculty do not recommend the use of plant species not yet introduced or with limited distribution in Florida that have a high risk of becoming invasive (Figure 2). The Predictive Tool is a weed risk assessment (WRA) protocol consisting of 49 questions used to evaluate species either new to the state or proposed for a new use (e.g., biomass planting). Weed risk assessments have proven to be a cost-effective tool where adopted. Economic modeling conservatively estimated that WRA implementation could save Australia $1.67 billion (USD) over a period of 50 years (Keller, Lodge, and Finnoff 2007). Gordon et al. (2008a) tested the accuracy of the Predictive Tool and determined that approximately 90% of major invaders were accurately categorized by the protocol across a variety of geographies (92% accuracy for Florida) (Gordon et al. 2008b).

Credit: Deah Lieurance, UF/IFAS

Questions presented in the Predictive Tool are answered by conducting thorough literature searches, using sources such as herbaria records, agency reports, and peer-reviewed primary literature. The questions in the Predictive Tool address the following areas:

- History of the species (i.e., domestication/cultivation)

- Biogeography (i.e., native range vs. proposed release sites, invasive status in other regions)

- Life history traits (i.e., plant type, growth habit, modes of reproduction)

- Ecology (i.e., persistence attributes, allelopathy, dispersal mechanisms)

Each question receives a numerical score between -3 and 5 points (most -1, 0, or 1), and conclusions are made based on the cumulative score. There are three potential outcomes of the Predictive Tool:

- Low Risk (<1 point)

- High Risk (>6 points)

- Moderate Risk/Evaluate further (between 1 and 6 points)

Thresholds for each conclusion were established by assessing known major invasive, minor invasive, and noninvasive plants. These thresholds prevent the introduction of many serious invasive species, limit the rejection of species that have not become invasive, and limit the number of species requiring further evaluation (Pheloung, Williams, and Halloy 1999).

If the conclusion is "evaluate further," an additional tool called the Secondary Screen is used. The Secondary Screen is a decision tree consisting of a small subset of risk assessment questions that vary based on life form (Daehler et al. 2004). Trees and shrubs are evaluated on shade tolerance, stand density, dispersal, and generation time. Herbaceous plants (and small-stature shrubs) are evaluated on their palatability to herbivores, their status as an agricultural weed, and their stand density (both decision trees are applied to vines) (Daehler et al. 2004). The addition of this supplemental tool has reduced the number of species requiring further evaluation by an average of 60% (Gordon et al. 2008a).

Like the Status Assessment, conclusions for the Predictive Tool are separately derived for north, central, and south Florida. USDA Hardiness Zones (http://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/PHZMWeb/) are incorporated into the climate tolerance questions to differentiate the risk of invasion in each zone. Additionally, the Status Assessment was revised to direct species to the Predictive Tool in the following two cases:

- Species that have not escaped into Florida's natural areas but are recent arrivals to the state or are known to cause problems in areas with climate and habitats similar to Florida

- Species that are being proposed for new uses (e.g., biofuel or biomass planting) that will result in significantly higher propagule pressure

Infraspecific Taxon Protocol

The Infraspecific Taxon Protocol (ITP) is primarily an internal tool for UF/IFAS faculty, particularly the UF/IFAS Assessment staff and the UF/IFAS Invasive Plant Working Group, to independently evaluate cultivars, varieties, hybrids, or subspecies of resident (nonnative species found in Florida) invasive species to determine if all taxa associated with particular species should receive the same recommendations.

UF/IFAS faculty can initiate an ITP evaluation when they seek university approval of a taxon whose resident species has received a "do not recommend" conclusion (e.g., to obtain UF/IFAS approval to release a cultivar for commercial use). UF/IFAS Assessment staff may also initiate an ITP evaluation if new subspecific taxa or hybrids are being recommended by UF/IFAS faculty or others. Initiation begins with the submission of a petition for assessment to the UF/IFAS Assessment. This petition must be accompanied with evidence demonstrating that the taxon has characteristics that will reduce its invasive potential compared to resident species. Examples of taxa that have been evaluated with the ITP include five cultivars of Eucalyptus grandis, seven cultivars of Ruellia, and nine Lantana camara cultivars. Three of the sterile Lantana camara cultivars have been trademarked and are commercially available (Figure 3). Even though the ITP is used infrequently, it provides a process to evaluate cultivars that may offer viable alternatives to popular agronomic or horticulture species that also happen to be common invaders.

Credit: Sandra Wilson and Zhanao Deng, UF/IFAS

The ITP consists of 12 questions to determine the following:

- If botanists/field personnel will be able to distinguish the taxon from the resident species (or other infraspecific taxa) in the field

- If the taxon can regress (or hybridize) to characteristics of the resident species

- The number of seeds or vegetative propagules the taxon produces

- Viability of pollen, seeds, or vegetative propagules

- If the taxon displays invasive traits that cause greater ecological impacts than the resident species

Depending on the answers, conclusions may be drawn from the ITP, or the infraspecific taxon may be directed to the Predictive Tool or the Status Assessment. Recommendations made directly from the ITP fall into the same possible categories outlined in the Status Assessment. If the ITP cannot be completed, then the conclusions for the resident species are applied to the infraspecific taxon. Recommendations for infraspecific taxa that have been assessed or evaluated using the ITP are listed in the online "Conclusions" table independently from the conclusions of the resident species.

Conclusion

The UF/IFAS Assessment website (http://assessment.ifas.ufl.edu) contains all information gathered by the UF/IFAS Assessment team. The "Conclusions" page is sorted by scientific name, common name, and region, and summarizes the recommendations for each species. The "Detailed Data" page includes the response forms, Predictive Tool data sheets, and ITP data sheets. Staff members also disseminate information in public presentations where they provide a detailed explanation of the history, purpose, and process of the UF/IFAS Assessment. The ongoing endeavors of the UF/IFAS Assessment will continue to provide recommendations for nonnative plants to help protect Florida's natural areas.

Notes

*IPBES refers to the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, an independent, international organization created to strengthen the science-policy interface for biodiversity and ecosystem services for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, long-term human well-being, and sustainable development.

**In March 2020, the Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council formally changed their name to the Florida Invasive Species Partnership.

References

Daehler, C. C., J. S. Denslow, S. Ansari, and H. Kuo. 2004. "A Risk-Assessment System for Screening out Invasive Pest Plants from Hawaii and Other Pacific Islands." Conservation Biology 18: 360–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00066.x

Diaz, S., J. Settele, E. Brondizio, H. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, ..., & K. Chan. 2019. "Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services." https://www.ipbes.net/sites/default/files/downloads/spm_unedited_advance_for_posting_htn.pdf

Fox, A. M., D. R. Gordon, and R. K. Stocker. 2003. "Challenges of Reaching Consensus on Assessing Which Non-native Plants Are Invasive in Natural Areas." HortScience 38: 11–13.

Fox, A. M., and D. R. Gordon. 2009. "Approaches for Assessing the Status of Non-native Plants: A Comparative Analysis." Invasive Plant Science and Management 2: 166–184. https://doi.org/10.1614/IPSM-08-112.1

Gordon, D. R., D. A. Onderdonk, A. M. Fox, and R. K. Stocker. 2008a. "Consistent Accuracy of the Australian Weed Risk Assessment System across Varied Geographies." Diversity and Distribution 14: 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2007.00460.x

Gordon, D. R., D. A. Onderdonk, A. M. Fox, R. K. Stocker, and C. Gantz. 2008b. "Predicting Invasive Plants in Florida Using the Australian Weed Risk Assessment." Invasive Plant Science and Management 1: 178–195.

Hiatt, D., K. Serbesoff‐King, D. Lieurance, D. R. Gordon, and S. L. Flory. 2019. "Allocation of Invasive Plant Management Expenditures for Conservation: Lessons from Florida, USA." Conservation Science and Practice 1: e51. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.51

Keller, R. P., D. M. Lodge, and D. C. Finnoff. 2007. "Risk Assessment for Invasive Species Produces Net Bioeconomic Benefits." PNAS 104: 203–207.

The Nature Conservancy. 2020. Stopping the Spread of Invasive Species. Arlington, VA. https://www.nature.org/en-us/about-us/where-we-work/united-states/florida/stories-in-florida/combating-invasive-species-in-florida/

Pheloung, P. C., P. A. Williams, and S. R. Halloy. 1999. "A Weed Risk Assessment Model for Use as a Biosecurity Tool Evaluating Plant Introductions." Journal of Environmental Management 57: 239–251. https://doi.org/10.1006/jema.1999.0297

Simberloff, D. 1994. "Why Is Florida Being Invaded?" In An Assessment of Invasive Non-indigenous Species in Florida's Public Lands, edited by D. C. Schmitz and T. C. Brown. 7–9. Technical Report No. TSS-94-100. Tallahassee: Bureau of Aquatic Plant Management, Division of Environmental Resources Permitting, Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

Vitousek, P., L. Loope, C. D'Antonio, and S. J. Hassol. 1995. "Biological Invasions as Global Change." In Elements of Change 1994, edited by S. J. Hassol and J. Katzenberger. 213–336. Aspen, CO: Aspen Global Change Institute.

Williamson, M., and A. Fitter. 1996. "The Varying Success of Invaders." Ecology 77: 1661–1666. https://doi.org/10.2307/2265769

Wunderlin, R. P. 1982. Guide to Vascular Plants of Central Florida. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.