Symptoms

Symptoms of potassium (K) deficiency vary among species, but always appear first on the oldest leaves. Older leaflets of some palms such as Dictyosperma album (hurricane palm) are mottled with yellowish spots that are translucent when viewed from below (Figure 1). In other palms such as Dypsis cabadae (cabada palm), Howea spp. (kentia palms) and Roystonea spp. (royal palms), symptoms appear on older leaves as marginal or tip necrosis with little or no yellowish spotting present (Figures 2 and 3). The leaflets in Roystonea, Dypsis, and other pinnate-leaved species showing marginal or tip necrosis often appear withered and frizzled.

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

In fan palms such as Livistona chinensis (Chinese fan palm), Corypha spp. (talipot palm), Washingtonia spp. (Washington palms), and Bismarckia nobilis (Bismarck palm), necrosis is not marginal, but is confined largely to tips of the leaflets (Figures 4 and 5). In Phoenix roebelenii (pygmy date palm), the distal parts of the oldest leaves are typically orange with leaflet tips becoming necrotic (Figure 6). The rachis and petiole of the leaves usually remains green, however, and the orange and green are not sharply delimited as with magnesium (Mg) deficiency. This pattern of discoloration holds for most palm species that show discoloration as a symptom.

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

In Phoenix canariensis (Canary Island date palm), leaflets show fine (1–2 mm) necrotic and translucent yellow spotting and extensive tip necrosis. These necrotic leaflet tips in most Phoenix spp. are brittle and often break off, leaving the margins of affected leaves irregular.

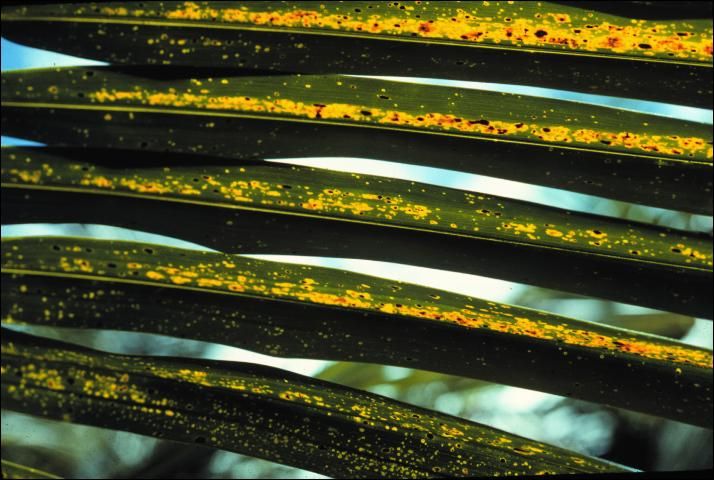

In Caryota spp. (fishtail palms) and Arenga spp. (sugar palms), chlorotic mottling is minimal or non-existent, but early symptoms appear as irregular necrotic spotting within the leaflets (Figures 7 and 8). In most other palms, including Cocos nucifera (coconut palm), Elaeis guineensis (African oil palm), Dypsis lutescens (areca palm), Chamaerops humilis (European fan palm) Hyophorbe verschafeltii (spindle palm), and others, early symptoms appear as translucent yellow or orange spotting on the leaflets and may be accompanied by necrotic spotting as well. As the deficiency progresses, marginal and tip necrosis will also be present. The most severely affected leaves or leaflets will be completely necrotic and frizzled except for the base of the leaflets and the rachis (Figures 9–11).

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

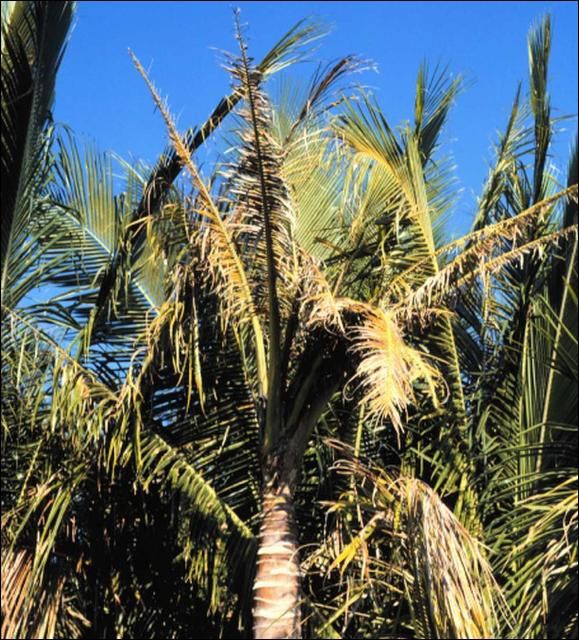

For all palms, symptoms decrease in severity from tip to base of a single leaf and from old to new leaves within the canopy (Figures 12 and 13). Because K deficiency causes premature senescence of older palm leaves, the severity of this deficiency is best measured not by the number of discolored and symptomatic leaves, but rather by the number of living leaves in the canopy. In severe cases, the canopy will contain only a few leaves, all of which will be chlorotic, frizzled, and stunted (Figures 14 and 15). The trunk will begin to taper (pencil-pointing) and death of the palm often follows.

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Cause

Potassium deficiency is caused by insufficient K in the soil, but can be induced or accentuated by high N:K or Ca:K ratios in the soil. Potassium is readily leached from sand or limestone soils which have very low cation exchange capacities.

Occurrence

Potassium deficiency is very common on palms grown in highly leached sandy soils. It is less common in container substrates. Potassium deficiency is perhaps the most widespread of all palm nutrient deficiencies, occurring in most palm-growing regions of the world. It is quite severe in southern Florida and much of the Caribbean region. Although most species of palms are susceptible to some degree, genera such as Veitchia, Adonidia, and Archontophoenix are notably resistant to K deficiency. Potassium deficiency is the leading cause of mortality in Roystonea growing in southern Florida landscapes.

Diagnostic Techniques

Visual symptoms alone may be sufficient for diagnosis of this disorder although leaf nutrient analysis may be helpful in distinguishing late stage K deficiency from manganese (Mn) deficiency (see ENH-1015 Manganese Deficiency in Palms https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ep267). These two deficiencies can be extremely similar from a distance, but close examination should reveal characteristic spotting and marginal necrosis in K deficiency or necrotic streaking for Mn deficiency (Figures 16 and 17). Potassium deficiency symptoms are also more severe toward the leaf tip and are less so at the leaf base. The reverse is true for Mn deficiency.

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

When sampling for leaf analysis, select 4 to 6 central leaflets from the youngest fully-expanded leaf. Soil analysis is not particularly useful for diagnosing palm nutrient deficiencies, since palm nutrient symptomology often bears little resemblance to soil nutrient profiles.

Management

Regular applications of K fertilizers will prevent K deficiency and treat palms already deficient. On sandy soils, or those having little cation exchange capacity, controlled-release K sources are much more effective than the easily leached water-soluble K sources. Sulfur-coated potassium sulfate has been shown to be the most effective and economical source for K in the landscape. When applying K fertilizers to correct an existing K deficiency, it is important to also apply about 1/3 as much Mg (also in a slow release form such as prilled kieserite) to prevent a high K:Mg ratio from causing an Mg deficiency problem. For severely K-deficient landscape palms, broadcast this 3:1 blend of sulfur-coated potassium sulfate and prilled kieserite uniformly to the soil under the canopy at a rate of 1.5 lbs per 100 sq ft of canopy area. This should be repeated in three months. Three and six months after that, a 1:1 mixture of the K:Mg blend and a balanced 8-2-12+4Mg palm maintenance fertilizer should be similarly applied at the rate of 1.5 lbs of fertilizer per 100 sq ft of canopy area, bed area, or entire landscape area. After one year, use only the 8-2-12+4Mg with micronutrients maintenance fertilizer at the above rate.

For mild to moderately K-deficient palms, application of the 8-2-12+4Mg palm maintenance fertilizer every 3 months should be sufficient to treat and prevent K deficiencies. Treatment of K deficient palms may require one to two years or longer, since the entire canopy of the palm may need to be replaced with new symptom-free leaves. Removal of discolored older K-deficient leaves on a regular basis has been shown to accelerate the rate of decline from this disorder and can result in premature death of the palm.

See also ENH-1009 Fertilization of Field-grown and Landscape Palms in Florida https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ep261 and ENH-1010 Nutrition and Fertilization of Palms in Containers https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ep262.

Selected References

Broschat, T.K. 1984. Nutrient deficiency symptoms in five species of palms grown as foliage plants. Principes 28:6–14.

Broschat, T.K. 1990. Potassium deficiency of palms in south Florida. Principes 34:151–155.

Broschat, T.K. 1994. Removing potassium deficient leaves accelerates rate of decline in pygmy date palms. HortScience 29:823. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.29.7.823

Bull, R.A. 1961. Studies on the deficiency diseases of the oil palm. 2. Macronutrient deficiency symptoms in oil palm seedlings grown in sand culture. J. West African Inst. Oil Palm Res. 3:254–264