Species Description

Class

Monocotyledonous plants

Family

Cyperaceae

Other Common Names of Yellow Nutsedge

Nut grass, chufa sedge, tiger nutsedge, and earth almond.

Other Common Names of Purple Nutsedge

Coco grass, java grass, nut grass, and red nutsedge.

Life Span

Both species are perennial plants.

Habitat

Both species are prevalent in lawns, cultivated areas, turf areas, landscape beds, gardens, fields, pastures, roadside, edges of forests, grasslands, riverbanks, irrigation canal banks, and disturbed areas (Figures 1 and 2). Both species are very persistent once established.

Credit: Chris Marble, UF/IFAS

Credit: Chris Marble, UF/IFAS

Distribution

Cyperus esculentus (yellow nutsedge) is found worldwide in warm and temperate zones. In the western hemisphere, it grows from southern Canada to northern Argentina. This plant is common throughout most of the United States and is native to North America.

Cyperus rotundus (purple nutsedge) is thought to have originated in India by some authors, but others believe that its origin is more widespread and include northern and eastern Australia (Parsons and Cuthbertson 1992). Other authors believe it is native to the tropical and subtropical old world, mainly Eurasia and Africa (Govaerts 2007). This species has been officially recorded in 92 countries (Holm et al. 1977) but is thought to occur in all countries with tropical or subtropical climates. Purple nutsedge is not as tolerant as yellow nutsedge to colder weather. In the United States, purple nutsedge is found primarily from Virginia to central Texas (USDA-NRCS, Plant Guide) but has also naturalized in parts of Arizona, California, and Oregon (SWSS 1995; Westbrooks 1998).

Growth Habit

Both species have an upright growth habit and can reach up to 36 inches in height.

Seedling

Seedlings are very rare, as both species spread almost exclusively via rhizomes and tubers (Stoller & Sweet 1987).

Shoot

The shoots of both yellow and purple nutsedge are triangular, borne individually from a tuber or basal bulb. Leaves arise from a central triangular stem and are three-ranked, or arranged in sets of three from the base, as well as V-shaped in the cross-section. The leaves in both yellow and purple nutsedge are thicker and stiffer than most grasses.

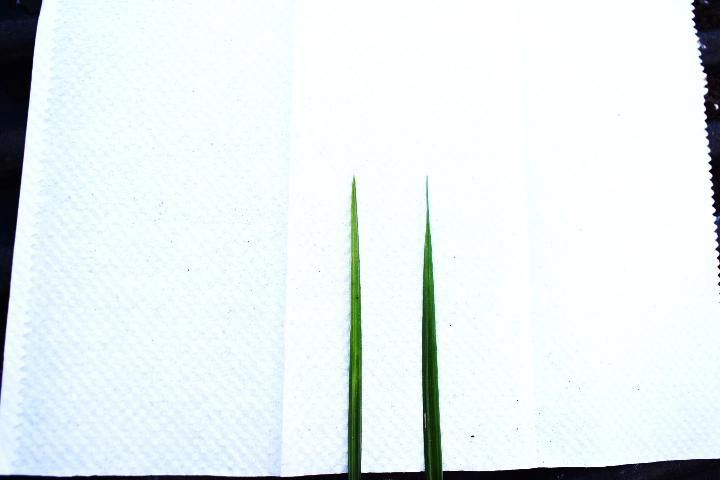

Yellow nutsedge leaves are 0.5 inches wide and 12 to 35 inches long. They are yellow-green, smooth, and shiny or waxy on the upper surface with long attenuated tips (Figure 3). Leaf blades of purple nutsedge are green, 0.2 to 0.5 inches wide, have a prominent midvein, and abruptly taper to a tip (Bryson and DeFelice 2009) (Figure 3). Purple nutsedge usually has shoots that are darker green when compared to yellow nutsedge.

Credit: Chris Marble, UF/IFAS

Roots, Rhizomes, Tubers, and Bulbs

Both species produce deep fibrous roots, rhizomes, and distinct tubers. Tubers are produced on rhizomes, or underground stems. Buds on the tubers sprout and grow to form new plants and eventually form patches up to 10 feet or more in diameter (UC-IPM 2017). Yellow nutsedge tubers grow at the ends of rhizomes, are mostly round, hard, smooth, have scales when immature, are 0.1 to 0.6 inches diameter, and brown to black in color. Purple nutsedge tubers grow in chains along the rhizomes; they are round to oblong and often irregular in shape, are 0.1 to 1.0 inches long by about 0.3 inches in diameter, covered with red to brown papery scales, and have roots (Sholedice and Renz 2006).

Inflorescence

The inflorescence (flowers) of yellow nutsedge consists of an umbel (a cluster of flowers originating from a central point) of spikes distributed throughout stalks of unequal length (1‒3 inches), are yellow-brown, golden, or straw colored, and are supported by leaf-like bracts as long or longer than the spikes (Bryson and DeFelice 2009) (Figure 4).

Credit: Annette Chandler, UF/IFAS

Within the continental United States, the inflorescence of purple nutsedge is umbel-like and contains unequally stalked spikes. The spikes are reddish-purple or reddish-brown in color (Wills 1998) (Figure 5).

Credit: Annette Chandler, UF/IFAS

Fruit and Seeds

Yellow nutsedge has tiny, single-seeded fruit (achenes) that are triangular in cross-section, blunt-headed, and yellowish-brown in color. Purple nutsedge does not typically produce seeds in the United States (UC-IPM 2017). Reproduction by seed is typically not a concern for either species as seed production and viability is low.

Similar Species

Yellow and purple nutsedge are very similar in appearance when young. The easiest way to identify which species is present is by examining the leaf tips (Figure 3), tubers, and root structures, and by examining the inflorescence if it is present (Figures 4‒5). Other sedge species such as globe sedge (Cyperus croceus) (Figure 6) and kyllinga (Kyllinga spp.) (Figure 7) can be distinguished from yellow and purple nutsedge by examining the infloresence.

Credit: Annette Chandler, UF/IFAS

Credit: Charles T. Bryson, USDA-ARS bugwood.org

Plant Biology

Both species are perennial and grow most prolifically during the summer months but can emerge and grow in all seasons in Florida. Nutsedges reproduce mostly by tubers. Tuber formation begins from 4 to 6 weeks after seedling emergence; however, the shoot can continue to grow while tubers are forming. A rhizome emerges from the tuber, which forms a basal bulb after growing towards the soil surface. From the basal bulbs, the shoot and fibrous roots emerge. Basal bulbs usually form within 3 inches of the soil surface, although purple nutsedge bulbs can occur at 4‒8 inches deep in the soil (Hauser 1962). During one growing season, especially if irrigation or rainfall is abundant and competition from other plants is minimal, yellow and purple nutsedge can produce 4 to 12 million tubers per acre (Hauser 1962; Horowitz 1972; Tumbleson and Kommendahl 1961).

Management

Physical and Cultural Control

Use of organic mulch materials such as pinebark, pinestraw, or wood chips at typical 2‒3-inch depths recommended in the landscape are not effective. Research has shown both nutsedge species can also eventually penetrate many landscape fabrics (Derr and Appleton 1989). Woven polypropylene weed mats used alone or in combination with mulch have shown the ability to suppress both species (Brosnan & DeFrank 2008; Chase et al. 1999). These fabrics are durable and commonly used in nursery production for preventing weeds in production areas. In landscapes, these fabrics could be used as they allow air and water to pass through, although proper installation in existing landscapes is difficult, as the fabrics often must be cut and pieced together around existing vegetation, which increases the chances of weed penetration. Organic mulch such as pinebark will usually be applied on top of the weed mat in landscape situations for aesthetic purposes. Over time, this mulch will degrade and other organic matter (grass clippings, leaves, etc.) will be deposited on top of the fabric, providing a suitable environment for other weed species to begin growing through the mat. These fabrics will break down over time, and species such as nutsedge can begin to emerge through the mats. The added cost and difficulty of removing weeds in areas where weed mats have been installed should be considered prior to installation (Derr and Appleton 1989).

Hand weeding will remove shoots, but they will rapidly regrow if tubers are not removed. It is rare for either species to be found growing in nursery containers if clean potting soil is used. Often, several annual sedges that reproduce via seed are misidentified as yellow or purple nutsedge in these cases. Both nutsedge species can become problematic in containers where recycled soil is used or field soil, compost, or other contaminated amendments are incorporated into potting substrates. It is very difficult to remove either species from a container by hand weeding. Prevention by cleaning equipment and using weed-free and fresh, uncontaminated potting soil is the best course of action.

Chemical Control

Before applying chemical weed controls, be sure to consult the latest information on weed control. The 2017 Southeast Pest Management Guide may provide specific chemical recommendations for controlling weeds. Additionally, always be sure to read the label before application to ensure safety.

Preemergence Control

Preemergence herbicides, including dimethanamid-p (Tower®) and pendimethalin + dimethanamid-p (FreeHand®), can provide some suppression of yellow nutsedge. S-metolachlor (Pennant Magnum®) can provide suppression of both yellow and purple nutsedge.

Postemergence Control

Postemergence herbicides, including sulfosulfuron (Certainty®), imazaquin (Sceptor T/O®), sulfentrazone (Dismiss®), halosulfuron (SedgeHammer® or ProSedge), and glyphosate (RoundUp®) are effective for controlling both yellow and purple nutsedge. Bentazon (Basagran® T/O) can be applied for control of yellow nutsedge. While primarily utilized as postemergence herbicides, both halosulfuron and sulfentrazone provide some preemergence activity on nutsedge. A more complete list of postemergence herbicides labeled for use in and around ornamentals to control nutsedge is listed in Table 2. It is important to note these postemergence herbicides will be much more effective when weeds are small (2 to 3 fully formed leaves) and actively growing. Repeated applications may be needed depending upon nutsedge growth stage and density. See individual product labels for use rates and application instructions.

References

Bryson, C. T., and M. S. DeFelice. 2009. Weeds of the South. University of Georgia Press. 467 p.

Chase, C. A., T. R. Sinclair, and S. J. Locascio. 1999. "Effects of soil temperature and tuber depth on Cyperus spp. control." WeedSci. 47: 467‒472.

Derr, J. F., and B. L. Appleton. 1989. "Weed control with landscape fabrics." J. Environ. Hort. 7: 129‒133.

Westbrook, R.G. 1998. "Invasive plants: changing the landscape of America." https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs/490.

Govaerts, R., and D. A. Simpson. 2007. World checklist of Cyperaceae. Kew Pub. Royal Botanic Gardens. 780 p.

Holm, L. G., D. L. Plucknett, J. V. Pancho, and J. P. Herberger. 1977. The world's worst weeds. University Press. 609.

Hauser, E. W. 1962. "Development of purple nutsedge under field conditions." Weeds. 10: 315-321.

Horowitz, M. 1972. "Growth, tuber formation and spread of Cyperus rotundus L. from a single tuber." Weed Res. 12: 348‒363.

Parsons, W. T., and E. G. Cuthbertson. 1992. Noxious weeds of Australia. Melbourne, Australia: Inkata Press. 698.

Patton, A. and D. Weisenberger. 2017. "Sedge control for turf professionals." https://www.extension.purdue.edu/extmedia/ay/ay-338-w.pdf

Sholedice, F., and M. Renz. 2006. "Yellow and purple nutsedge: ornamental and turf guide." http://aces.nmsu.edu/ces/plantclinic/documents/nutsedges-w-12.pdf

Southern Weed Science Society (SWSS). 1995. Weeds of the United States. Compact disk for Windows®3.1 or Windows® 95 or higher. 1508 W. University Avenue, Champaign, Illinois.

Tumbleson, M. E. and T. Kommedahl. 1961. "Reproductive potential of Cyperus esculentus by tubers." Weeds. 9: 646–653.

United States Department of Agriculture–Natural Resources Conservation Service (USDA-NRCS). 2017. "Plant Guide." https://plants.usda.gov/plantguide/pdf/pg_cyro.pdf

Wills, D. G. 1998. "Comparison of purple nutsedge (Cyperus rotundus) from around the world." Weed Tech. 12: 491‒503.

Table 1. Preemergence herbicides labeled for use in ornamentals for suppression of nutsedge.

Table 2. Postemergence herbicides labeled for use in ornamentals for control of nutsedge.