What is Lymphocystis?

Lymphocystis is a chronic disease of freshwater and marine fishes caused by infection with an iridovirus known as Lymphocystivirus or Lymphocystis disease virus (LCDV), which is a member of the family Iridoviridae. Infection results in the development of pebble or wart-like nodules most commonly seen on the fins, skin, or gills, although other tissues may be affected. Although the disease has been seen worldwide in numerous species since its first description in 1874, its viral cause was not identified until 1962. The lymphocystiviruses are considered much less pathogenic (disease-causing) than their iridoviral relatives, the ranaviruses and megalocytiviruses, which can cause severe, systemic disease with higher mortalities.

Although lymphocystis disease normally does not cause significant mortalities, it does cause unsightly growths on fish that reduce their marketability, and in some cases, severely infected fish may die.

Which fish species are susceptible?

Lymphocystis disease has been reported in over 125 different marine and freshwater fish species from 34 different families. It affects evolutionarily- advanced orders of bony fishes (teleosts), including cichlids (Cichlidae), killifishes (Cyprinodontidae), gouramies (Osphronemidae), sunfishes (Centrarchidae), gobies (Gobiidae), butterflyfishes (Chaetodontidae), damselfish/clownfish (Pomacentridae), dottybacks (Pseudochromidae), snook (Centropomidae), drum (Sciaenidae), sea basses (Serranidae), and many others.

Lymphocystis does not affect less advanced orders, including catfish (Order Siluriformes), cyprinids (such as goldfish, koi, barbs, or danios; Family Cyprinidae) or salmonids (Family Salmonidae).

What are typical signs of disease?

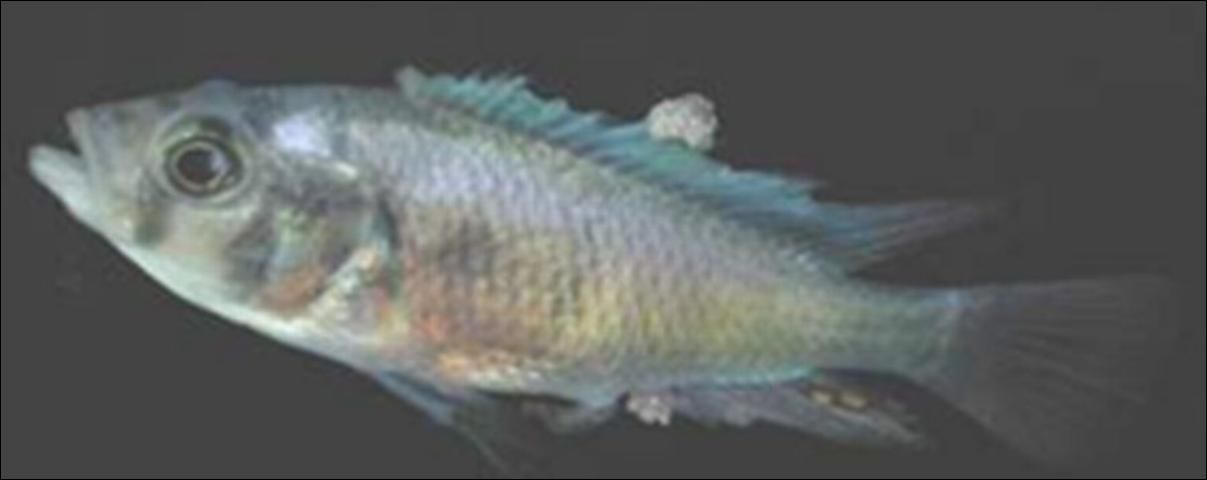

The most obvious sign is the appearance of small to moderate-sized, irregular, nodular, wart-like growths on the fins, skin, or gills (Figures 1 and 2). These may be cream- to gray-colored but can be other colors if they appear under pigmented areas. These may appear over the course of days and may last for weeks.

Credit: Roy Yanong, UF/IFAS

Credit: Roy Yanong, UF/IFAS

Pop-eye (exophthalmia; marked protrusion of the eye) has also been seen and results from lymphocystis masses in or behind the eye pushing the eyeball out.

Fish with lymphocystis normally do not behave differently from uninfected fish in the same group. However, if there are large numbers of nodules on the body or fins, or if they are covering a large portion of the gills, these may alter swimming or breathing patterns.

What are these nodules?

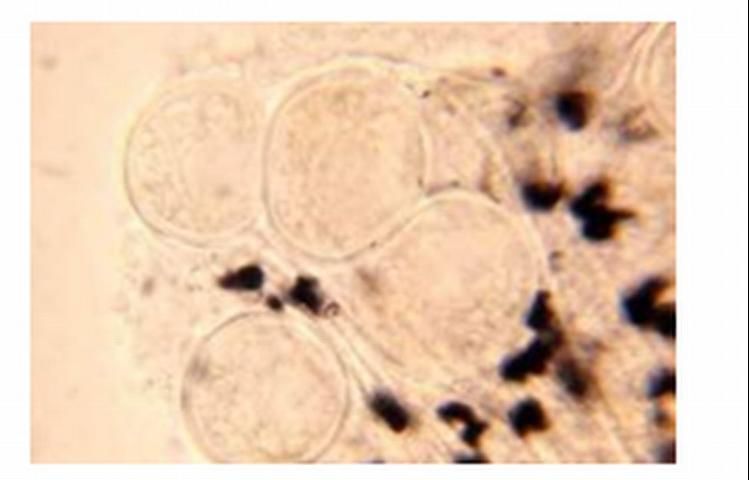

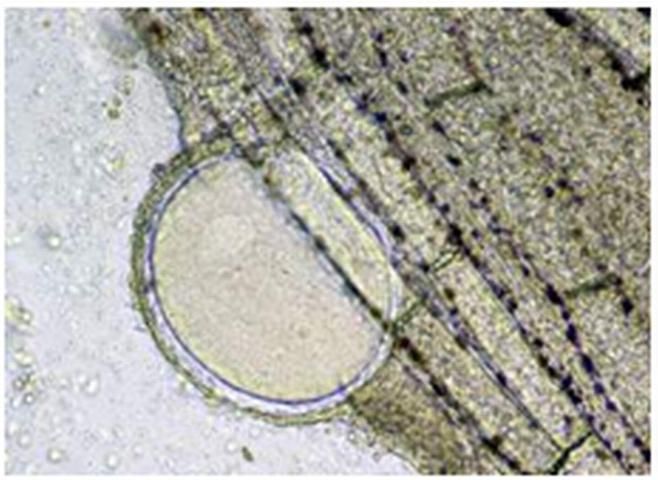

The nodules are actually clustered groups of greatly enlarged, infected cells known as fibroblasts, which are part of the connective tissues in the fish (Figures 3 and 4). These infected cells are 50,000–100,000x larger in volume than normal cells because they have become "virus factories," using the infected cell's machinery to produce more virus, and thus are filled with virus particles. After these "virus factory cells" have completed their production of virus particles, the cells will burst and shed virus into the environment.

Credit: Roy Yanong, UF/IFAS

Credit: Roy Yanong, UF/IFAS

Normal fibroblasts are approximately one hundredth of a millimeter (0.01 mm) in diameter. The individual infected cells, on the other hand, can be from one tenth of a millimeter—0.1 mm—to over 2 mm. Each infected cell is surrounded by a thick membrane. Fibroblasts are connective tissue cells normally found throughout the body, and so lymphocystis nodules may be seen internally as well as externally. However, fibroblasts in the skin, fins, or gills are more commonly affected.

How do I tell if my fish has lymphocystis?

In addition to seeing the wart-like growths on the fins, skin, or gills, a wet mount (fresh) biopsy of these growths (careful removal of one of these growths from the skin, fins, or gills) should be examined under the microscope. A strong tentative diagnosis of lymphocystis can be made based on seeing round to oval, grape, or balloon like structures, often in clumps (see Figures 3 and 4).

Fish may also be infected with lymphocystis without having obvious lesions that are visible with the naked eye. These fish may have smaller infected cells or may have one or more internal organs infected (e.g., inside the eye, spleen, or other organs). Lymphocystis, in these cases, may only be seen after microscopic examination of a wet mount (fresh) biopsy of suspected infected tissues, or by using more advanced techniques such as histopathology, electron microscopy, or molecular methods.

For an accurate diagnosis, work with a fish health professional or fish disease diagnostic laboratory if you suspect your fish have lymphocystis.

Can lymphocystis be confused with any other diseases?

Yes. In early stages of the disease, the nodules may be relatively small and may be confused with the parasites Ichthyophthirius multifiliis (Ich, freshwater white spot disease), Cryptocaryon irritans (marine white spot disease), digenean trematodes ("grubs"), or heavy infection with Epistylis (a stalked, ciliated, protistan parasite). Lymphocystis nodules may also be confused with epitheliocystis (an intracellular bacterial disease), clumps of fungus, or mucus tags. Some skin neoplasias (cancers) may also be confused with lymphocystis.

Because of the potential confusion with other disease agents, diagnosis of lymphocystis should be accomplished by a qualified fish health professional to rule out these other potential causes.

What factors contribute to development and spread of lymphocystis disease?

Lymphocystis is spread by fish-to-fish contact or contact with infected tissues. External trauma from spawning, aggression, parasites, or handling can facilitate infection and spread. In addition, crowding, shipping, and other stressors appear to trigger disease outbreaks. Lymphocystis does not appear to be spread by vertical transmission (i.e., from parents to offspring via infection of eggs or sperm).

Although all contributing factors are not known, there do appear to be different genetic variants or possibly "species" of Lymphocystivirus. Each of these affects a different group of fish. The virus that causes lymphocystis has been difficult to work with, but experts have officially designated four Lymphocystivirus species, Lymphocystis disease virus 1 (LCDV1), Lymphocystis disease virus 2 (LCDV2), Lymphocystis disease virus 3 (LCDV3), and Lymphocystis disease virus 4 (LCDV4). Several other variants have been suggested and may be determined to be separate species but these have not yet been officially accepted by all virus experts.

Based on clinical observations of mixed species groups and other anecdotal evidence, there may be additional strain variations and/or differences in individual fish species sensitivity to infection. In mixed natural or aquarium populations of fish, typically only one or two species will be infected. However, in experimental settings, multiple species can be infected by direct exposure to infected tissues.

What happens to infected fish?

Lymphocystis is usually a self-limiting disease, meaning that, in most cases, the lesions will clear up after a few weeks in warmwater fish species (up to 6 weeks in cool or coldwater species). However, because of the unsightly growths, fish normally cannot be sold during this time. If a fish has numerous lesions and/or lymphocystis nodules cover a large portion of important organs (e.g., the gills), there may be some impairment and greater chance of secondary infections by bacteria, parasites, or fungi that can now more easily infect the fish and help contribute to mortalities.

Can fish with lymphocystis be treated?

Currently, there is no good treatment that will speed up recovery from this disease. Most often, the disease must run its course in an affected fish. Fortunately most cases of lymphocystis in warmwater fish will resolve on their own after a few weeks, as long as husbandry is good (good water quality/chemistry, good nutrition, correct population densities, optimal social groups) and as long as other stressors have been eliminated. Although it is not an ideal solution, at present, the best option is to hold fish for several weeks (longer for cool and cold water fish) until the lesions have cleared.

Because lymphocystis disease tends to develop in parts of tissues that are less exposed to the immune system (e.g., at the periphery, away from blood vessels that carry immune cells) and in tissues with a thick hyaline membrane that may "hide" these cells, an immune response normally does not develop until after cells have burst and released virus. There is some evidence that fish infected with lymphocystis will develop less pronounced lesions if they are re-infected or if lesions recur.

Culling (removing) infected fish from a population may help reduce overall loads of virus in the system as well as infection rate, but it is difficult to cull all affected fish because some infections may not be visible with the naked eye, and many less severely infected fish may remain in the population to potentially infect other fish. Culling, therefore, may not be as effective a measure for aquacultured populations as for hobbyists or display aquaria. Culled fish can be isolated until their lesions resolve, but lesions may recur. If they do, they will most likely be less severe.

What can I do to prevent or reduce the likelihood of lymphocystis infection in my fish population and/or to reduce the severity of outbreaks?

Quarantining any new fish coming into your facility for at least 1–2 weeks (although longer periods, 30–60 days are preferred) and daily observation of these fish during this time will help alert you to any potential outbreaks of lymphocystis caused by shipping or acclimation stressors, and will also help increase the fish's immunity. Removal and/or isolation of affected fish may help reduce spread or severity. However, it is likely that other fish in the group are also infected, so removal and/or isolation of grossly affected fish will help reduce the number of active "shedders" and carriers of the virus.

As with other diseases, making sure water quality and husbandry practices as a whole are optimal, being careful with handling, avoiding overcrowding, and reducing or eliminating unnecessary stressors (including parasites) that may result in physical trauma will all help reduce the potential for infection and spread.

Use clean water (a protected water source that has not been exposed to the virus or other potential disease-causing organisms): if your water source contains fish with lymphocystis, this will increase your risk as well.

Be sure to check your own fish carefully and work with a fish health professional if you suspect you may have lymphocystis or the fish population has a history of the disease. Remember that cyprinids (members of the carp family, including goldfish, koi, barbs, rasboras, danios, and rainbow and redtail black sharks), catfishes, and salmonids do not get lymphocystis.

Look for small to medium-sized nodules or warts on the fins, skin, or gills of your fish. Although other organs may be infected, growths on the fins, skin, and gills are more common. Because lymphocystis lesions may not always be visible to the naked eye, fish tissues may still need to be examined microscopically. Biopsies of the skin, fins, and gills, especially from areas that appear to have some subtle abnormalities, should be examined under the microscope for evidence of enlarged cells typical of lymphocystis (see Figures 3 and 4). If any nodules are seen, these should be biopsied and examined.

If I want to disinfect equipment after handling fish with lymphocystis, what can I use?

Experimental studies have shown that iridoviruses can be inactivated with any of the following compounds, after 15 minutes at 77°F (25°C): potassium permanganate (100 mg/L or higher), formalin (2000 mg/L or higher), or sodium hypochlorite (liquid bleach—various formulations) at 200 mg/L or higher. Be sure to use proper precautions (adequate ventilation and personal protective equipment, e.g., gloves, goggles, respirator) when handling these chemicals. In addition, iridoviruses may also be inactivated by raising the pH to 11 or greater for a minimum of 30 minutes or with high temperatures (122°F [50°C] or greater for 30 min).

References and Recommended Reading

Hadfield, C. and Clayton, L. 2021. Clinical Guide to Fish Medicine. Wiley Blackwell. Hoboken, New Jersey. Pp. 421-422.

Wolf, K. 1988. Chapter 22. Lymphocystis disease. In Fish Viruses and Fish Viral Diseases. Cornell University Press. Ithaca, NY. Pp. 268–291.

ICTV (International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses) online. https://ictv.global/report/chapter/iridoviridae/iridoviridae/lymphocystivirus Accessed February 5, 2024.