This is one in a series of fact sheets discussing common foodborne pathogens of interest to food handlers, processors, and retailers.

What causes a Clostridium perfringens-associated foodborne illness?

The bacterium Clostridium perfringens causes one of the most common types of foodborne gastroenteritis in the United States, often referred to as perfringens food poisoning (FDA 2012). It is associated with consuming contaminated food that contains great numbers of vegetative cells and spores that will produce toxin inside the small intestine. There are two forms of disease caused by C. perfringens: gastroenteritis and necrotizing enteritis. The latter disease, also known as pig-bel disease, is not common in the United States. It is often associated with contaminated pork and can be very severe (FDA 2012).

According to estimates by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as many as one million individuals are affected by C. perfringens each year (Grass et al. 2013; Scallan et al. 2011; CDC 2024a), although only a fraction of these are recorded. It was also estimated that C. perfringens accounts for 438 hospitalizations and 26 deaths annually in the United States (Scallan et al. 2011). The number of foodborne illnesses associated with C. perfringens is likely under-reported due to the mildness of symptoms, brief illness duration (less than 24 hours), and lack of routine testing by public health officials. The average cost per case (cost-of-illness model includes estimates for medical costs, pharmaceutical costs, productivity losses, possible chronic conditions, and illness-related death) of C. perfringens in 2010 was $482 (Scharff 2011).

Outbreaks Associated with Clostridium perfringens

While outbreaks of C. perfringens are common, they do not become major headlines because the typical symptoms of the illness are mild and deaths are extremely rare. Table 1 outlines several confirmed outbreaks of C. perfringens that were identified by the CDC in 2021.

What is Clostridium perfringens?

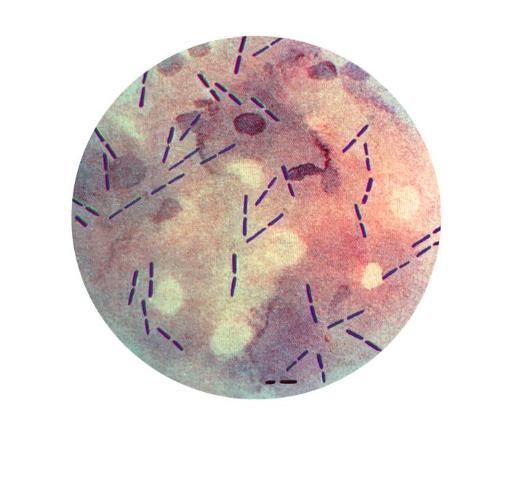

Clostridium perfringens is an anaerobic, Gram-positive, bacterial pathogen capable of forming endospores. These tough, dormant spores allow for the protection of the bacteria during times of environmental stress (e.g., lack of water, high temperature, etc.) (Cornell 2017). Sporulation allows C. perfringens to survive the cooking process. Foods must be kept at 140°F (60°C) or higher after cooking to prevent the growth of the surviving endospores (CDC 2024a). While the endospores are not detrimental to humans, spores can change into potentially harmful vegetative cells if exposed to inadequate cooking temperatures and then allowed to cool at temperatures between 54°F (12°C) and 140°F (60°C) for several hours. The optimal growth temperatures of C. perfringens range between 109°F (43°C) and 117°F (47°C) (CDC 2024a). The vegetative cells can produce a toxin that causes gastrointestinal illnesses in humans (Grass et al. 2013).

Clostridium perfringens is found not only in soil and sediment but is present as a part of the normal intestinal flora of animals and humans. Thus, the organism can be found in sewage and in areas prone to animal and sewage contamination. Clostridium perfringens spores have been isolated from raw and cooked foods (Grass et al. 2013).

Credit: CDC [PHIL #14346]

How is Clostridium perfringens spread?

Clostridium perfringens thrives in high-protein foods of animal origin, such as meat and meat products, meat dishes, stews, soups, gravies, and milk (see outbreak data in Table 1). Occasionally, poultry products, pork, lamb, fish, shrimp, crab, legumes (beans), potato salad, and macaroni and cheese may contain C. perfringens. These protein-containing foods, when kept at improper storage temperatures, between 54°F (12°C) and 140°F (60°C), provide the greatest risk of infection and disease from C. perfringens. This is because spores present after cooking can germinate and potentially grow to high, dangerous numbers. The danger zone exists between 109°F (43°C) and 117°F (47°C) (CDC 2024a). Foods need to be cooled rapidly through this zone on their way to 40°F (4.4°C). The 2017 Food Code recommends that food should not be in this zone for more than two hours (FDA 2017). If reheating foods, it is recommended to heat it to at least 165°F (74°C) (CDC 2024a). For most illnesses involving these foods, keeping food in the danger zone too long was identified as the cause of the C. perfringens food poisoning.

Symptoms of Clostridium perfringens Illness

Gastroenteritis, which is the inflammation of the stomach and/or intestines, can occur 6 to 24 hours after consuming food contaminated with large numbers of the vegetative form of C. perfringens (CDC 2024a). The infective dose for C. perfringens is 100,000 to 1,000,000 cells/spores per gram of food (FDA 2012). Symptoms include severe abdominal cramps and pain, diarrhea, and flatulence (CDC 2024a). Because most symptoms usually last approximately 24 hours, many infected individuals believe they had a case of the "24-hour flu" (Birkhead et al. 1988). Occasionally, less severe symptoms may continue for one to two weeks (CDC 2024a). These longer episodes are usually associated with the extremely young or the elderly. In severe cases, dehydration and other complications can result in the death of the infected individual.

The gastrointestinal symptoms, typically without fever, precede confirmation by toxin or organism detection in fecal (stool) samples of affected individuals (CDC 2024a). The illness can also be confirmed by the detection of C. perfringens in the suspected food that was consumed (Birkhead et al. 1988; Dailey et al. 2012).

Another disease caused by C. perfringens is called enteritis necroticans or pig-bel disease. It is associated with developing countries, and it is often fatal (Petrillo et al. 2000; FDA 2012). The disease is caused by C. perfringens type C, which is often associated with eating contaminated pork or pig intestines (Gui et al. 2002). It can cause vomiting, abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, swollen abdomen, and necrosis of small intestines (Songer 2010; Gui et al. 2002; FDA 2012). The disease is very rare in the United States. However, it was reported in two diabetic patients, a child and an adult, who were diagnosed with pig-bel disease in 1998 and 2001, respectively (Petrillo et al. 2000; Gui et al. 2002).

Which populations are at high risk for Clostridium perfringens foodborne illness?

Hospitals, nursing homes, prisons, and school cafeterias are locations that pose the highest risk of a C. perfringens outbreak (CDC 2024a). In these settings, foods are cooked but may not be kept at safe, adequate temperatures prior to serving. Although C. perfringens may be present in small numbers in raw foods, improper storage and handling of these foods could allow the pathogen to grow to high, harmful numbers (CDC 2024a; FDA 2017). The age group with the highest number of illnesses due to C. perfringens is those between the ages of 20 to 49, with men being more likely to become ill than women (Grass et al. 2013). Immunocompromised individuals may experience longer symptoms and complications (Grass et al. 2013).

How can Clostridium perfringens foodborne illness be controlled and prevented?

Since C. perfringens can grow rapidly at elevated temperatures and form heat-resistant spores, preventing growth is paramount. Foods should be cooked to an internal temperature of 165°F (74°C) or higher for 15 seconds to inactivate the pathogen's vegetative cells. Additionally, the cooked food must be chilled rapidly to 41°F (5°C) or less or kept at hot holding temperatures of 140°F (60°C) or higher to prevent any activation and growth of C. perfringens spores.

Large portions of meat, broth, gravies, and other foods commonly associated with C. perfringens must meet specific guidelines noted in the 2017 FDA Food Code. These guidelines specify that potentially hazardous food should be cooled within two hours from 135°F (57°C) to 70°F (21°C) and within six hours from the initial 135°F (57°C) to 41°F (5°C). Large containers of food may take an extended period of time to cool to 41°F (5°C) and, therefore, should be separated into smaller portions. Additionally, storage containers should be stacked to encourage good airflow above and below to facilitate rapid cooling. Leftover foods should be reheated to 165°F (74°C) or greater while stirring and rotating and allowed to stand covered for two minutes. This should inactivate any vegetative cells that have germinated during cooling, as well as other foodborne pathogens that may have cross-contaminated the food (CDC 2024a; FDA 2017).

Best Ways to Avoid Illness

The best way to prevent foodborne illness associated with C. perfringens is to observe a few proper control measures in food preparation, storage, and temperature controls. These include measures such as the rapid, uniform cooling of cooked foods; making sure cooked foods remain hot after they are cooked; and when reheating cooled or chilled foods, all parts of the foods reach a minimum temperature of at least 165°F (74°C) (FDA 2017).

References

Birkhead, G., R. L. Vogt, E. M. Heun, J. T. Snyder, and B. A. McClane. 1988. "Characterization of an Outbreak of Clostridium perfringens Food Poisoning by Quantitative Fecal Culture and Fecal Enterotoxin Measurement." Journal of Clinical Microbiology 26 (3): 471–474. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.26.3.471-474.1988

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2024a. “About C. perfringens Food Poisoning.” Accessed November 13, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/clostridium-perfringens/about/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2024b. “BEAM (Bacteria, Enterics, Ameba, and Mycotics) Dashboard.” National Center for Emerging Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID). Accessed November 13, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/dfwed/BEAM-dashboard.html

Cornell University College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (Cornell CALS). n.d. “Bacterial Endospores.” Microbiology. Accessed November 13, 2024. https://cals.cornell.edu/microbiology/research/active-research-labs/angert-lab/epulopiscium/bacterial-endospores

Dailey, N. J., N. Lee, A. T. Feischauer, Z. S. Moore, E. Alfano-Sobsey, F. Breedlove, A. Pierce, et al. 2012. "Clostridium perfringens Infections Initially Attributed to Norovirus, North Carolina, 2010." Clinical Infectious Diseases 55 (4): 568–570. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cis441

Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2012. “Clostridium perfringens.” Bad Bug Book: Foodborne Pathogenic Microorganisms and Natural Toxins Handbook. https://www.fda.gov/media/83271/download

Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2017. Food Code. US Public Health Service. https://www.fda.gov/media/110822/download

Grass, J. E., L. H. Gould, and B. E. Mahon. 2013. "Epidemiology of Foodborne Disease Outbreaks Caused by Clostridium perfringens, United States, 1998–2010." Foodborne Pathogens and Disease 10 (2): 131–135. https://doi.org/10.1089/fpd.2012.1316

Gui, L., C. Subramony, J. Fratkin, and M. D. Hughson. 2002. "Fatal Enteritis Necroticans (Pigbel) in a Diabetic Adult." Modern Pathology 15 (1): 66–70. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880491

Petrillo, T. M., B. M. Consuelo, J. G. Songer, C. Abramowsky, J. D. Fortenberry, L. Meacham, A. G. Dean, H. Lee, D.M. Bueschel, and S. R. Nesheim. 2000. "Enteritis Necroticans (Pigbel) in a Diabetic Child." The New England Journal of Medicine 342 (17): 1250–1253. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200004273421704

Scallan, E., R. M. Hoekstra, F. J. Angulo, R. V. Tauxe, M. -A. Widdowson, S. L. Roy, J. L. Jones, and P. M. Griffin. 2011. "Foodborne Illness Acquired in the United States—Major Pathogens." Emerging Infectious Diseases 17 (1): 7–15. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1701.P11101

Scharff, R. L. 2011. "Economic Burden from Health Losses Due to Foodborne Illness in the United States." Journal of Food Protection 75 (1): 123–131. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0362028X2300426X

Songer, J. G. 2010. "Clostridia as Agents of Zoonotic Disease." Veterinary Microbiology 140 (3–4): 399–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.07.003

Resources

Schmidt, R. H., R. M. Goodrich, D. L. Archer, and K. R. Schneider. 2018. “General Overview of the Causative Agents of Foodborne Illness.” FSHN033. University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fs099

Table 1. Outbreaks of Clostridium perfringens in 2021. An en-dash (–) indicates no available data.